This roundtable was inspired by Trina Robbins’ Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896–2013 (and by discussions on websites such as Comics Worth Reading). To paraphrase, Robbins concluded that there’s a lot of graphic autobiography by women, but it seems like there aren’t a lot of graphic novels. I wanted to get various points of view on the subject, so I asked Ellen Forney (whose personal work is often autobio-based), Megan Kelso (whose comics I consider literary) and Raina Telegemeier, who cartoons in both modes, to discuss this topic. I used Hillary Chute’s Graphic Women to help generate discussion points. (I also provided a quick terminology guide defining my terms for the participants.) — Kristy Valenti

(Another portion of this conversation will appear in The Comics Journal #303.)

RAINA TELGEMEIER: I’m Raina Telgemeier. I am mostly an autobiographical cartoonist. The work I’m best known for is a book called Smile, which is the story of my adolescent dental trauma. So, in middle school I knocked out my two front permanent teeth, and had to spend four and a half years getting my face readjusted so I could be normal again, and I wrote Smile about that experience. Smile was published by Scholastic. It ended up hitting a nerve, I guess, with like 9- and 10-year-old girls who were also going through orthodontia and teenage stuff in their own lives. And so, it’s done pretty well by me.

And I did a book called Drama, which is not autobiographical but is inspired by a lot of the high school theater experience that I enjoyed when I was younger. I am working on a book now called Sisters, which is a companion to Smile but has nothing to do with braces. And that is going to be a story about my relationship with my younger sister, who could not be more different from me — as two sisters could possibly be. It’s about our childhood, it’s about struggling with our parents as they start to have problems in their marriage, and it’s not out yet. So that was just a huge spoiler. It’ll be out this September [laughter] from Scholastic. And before I did this for Scholastic I was doing short-form autobiography in a series of minicomics called Take-Out and those were about my childhood, and my adult days as well. So that’s me!

MEGAN KELSO: My name is Megan Kelso and I’ve been doing comics since 1991. I started out doing a comic called Girlhero, which I self-published six issues of, and since then I’ve done three books. One was a collection of the stuff from Girlhero [Queen of the Black Black], one was another collection of short stories [Squirrel Mother]. And the third, the most recent one, which came out in 2010, was a graphic novel called Artichoke Tales. And I am currently at work on my fourth book, which will be another collection of short stories. And none of this work is autobiographical in the sense of, like, a memoir. But I would say that almost all of my stories, like almost any writer or cartoonist, has elements of autobiography that are woven into made-up stories. But, if you know me, or know my family, if you read my work, you would probably occasionally see glimmers of stuff that was familiar to you. But I’ve never ever thought of myself as an autobiographical cartoonist. I’ve thought of myself as a writer and drawer of fictional stories. That’s it! [Forney laughs.]

ELLEN FORNEY: I’m Ellen Forney. I have been a professional cartoonist since ’92, and here in Seattle, in the mid-’90s, I was part of a small group of young cartoonists who were very dedicated, and Megan was one of them. So, we’ve known each other, and our careers have — I don’t know that I would say that they intertwined, but we definitely have been side by side, to one degree or another.

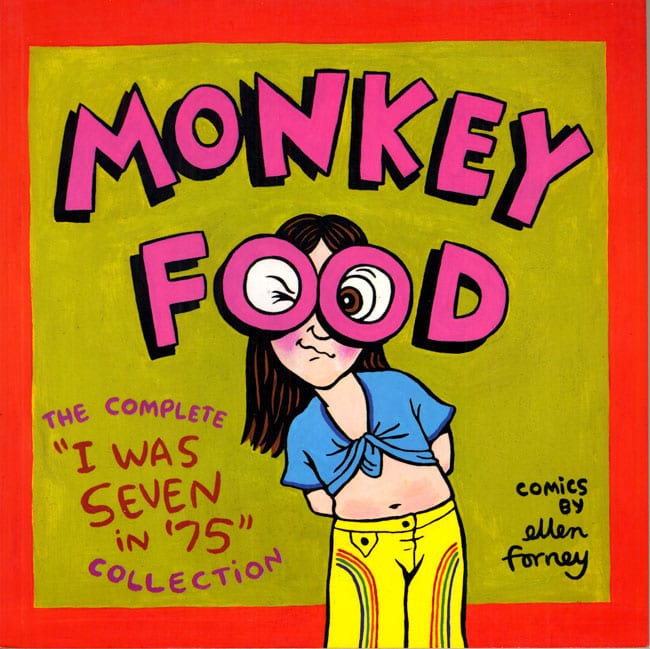

I have put out a number of books. The first three that I put out were collections of shorter work. For years, I considered myself something more of a “graphic essayist.” And so the first one I put out is called Monkey Food, and that’s a collection of comics that I did for a few different weekly papers, called I was Seven in ’75, about growing up in my funky family in the ’70s. And then I Love Led Zeppelin, which is a collection of work that I did for newspapers and magazines. And then Lust, which is a collection of weekly cartoon adaptations of kinky personal ads. It’s really hard for me to describe what they are, because they’re one panel, but they’re more like one-panel narrative portraits of a situation: so, no easy description for that. Anyway, when people say I’m a pornographer, which happens sometimes, that’s generally what they’re referring to.

But my first full-length book, my graphic memoir, just came out in 2012. And I would say that that has been a milestone. It’s about my experience of being bipolar. And I also did a lot of research about other artists and writers through history who had mood disorders and then a lot of research of studies that correlated mood disorders and creativity. So that has been the focus of a lot of the work that I’ve done, a lot of the things that I’ve been doing since then. And I guess I would add, just quickly, that a lot of my work is autobiographical — not all of it, but a lot of it — and that I also teach comics and graphic novels as literature at Cornish College of the Arts.

KRISTY VALENTI: So my idea for this roundtable was to talk about if women’s graphic works were predominately tied to the autobio genre. I worked on Pretty in Ink, which is Trina Robbins’ recent history of women cartoonists. At the end she said, “There’s a lot of graphic autobiography [by women], but it seems like there aren’t a lot of graphic novels,” as in fictional work, or “literary” work.

I was wondering if that’s true, and if so, why? I was hoping you could help me, talking about your own experiences.

KELSO: It seems like there are a lot of graphic memoirs. And I’m not sure if there’s a difference in the number by men or by women. Are you asking us specifically about women, and is there something about … could you clarify what your question is?

VALENTI: Yes. Another way I’ve seen it phrased is: when you talk about “literary” cartoonists, people mention Dan Clowes, or Charles Burns, or Chris Ware, or people like that. I don’t know if there’s a woman, a “literary cartoonist,” who you would mention in that group. (I would, because I’ve been doing this for so long, and I’m familiar with many cartoonists.) When you talk about [“literary”] women cartoonists, the people who come to mind are people like Alison Bechdel or Marjane Satrapi. So that’s what fascinates me, and I was hoping to explore that with you.

“The personal is political” is feminist. For women, is telling your story a political act in a way that it’s not for men?

FORNEY: I was thinking about that, feeling compelled to tell autobiography. I think probably that any memoirist struggles with “am I just being an egomaniac, is this narcissism?” and then have to take a step back, and be like, “Well, if it has import beyond me, then it works.” Don’t forget how many memoirs have been important to you, and it’s OK. I mean, that said, it does seem, I have to admit, that most of the comics that I have found most inspiring have been autobiographical, by women. When I first decided, “Yes, I want to be a cartoonist,” I was most attached to the Twisted Sisters collection, and Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch out For. And so there were really a lot of them: Dori Seda’s work, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s work. It all felt very real to me, very accessible. I’m kind of at a loss as to why that makes such an impact.

TELGEMEIER: I’m coming from a similar place, but for me it was comic strips that I came up through. And so the cartoonist that always spoke the loudest to me was Lynn Johnston, with For Better or For Worse, and it’s similar that, that’s not 100 percent autobiography, but it’s really coming from a place of her own life, and her own stories, and inspired by things that have happened to her.

I like observational cartoonists. I like cartoonists who see the world and interpret it in a way that feels real or says something true. Why that doesn’t necessarily translate into literary comics, I’m really not sure. But it might just be that that’s historically true, but that it will not always be true. I’m looking now at my bookshelf and thinking about all of the women who are doing things at the moment that you might not say, well, Vera Brosgol is the most well-known cartoonist in the world in 2014, but that might change. Twenty years from now, people might look back and say that she was a prime writer of our time, and was doing literary work that had a personal feeling, but was still fiction. And there are several other examples that I can cite, but —

KELSO: Who was the cartoonist you just mentioned?

TELGEMEIER: Vera Brosgol, who did the book Anya’s Ghost. She is a storyboard artist who works at Laika in Portland, and she’s been drawing comics since she was a teenager and putting them up on the Internet. And Anya’s Ghost was her first full-length graphic novel work, and it’s fantastic. And First Second’s actually putting out a lot of really nice literary work: some of it by women, some of it by men, a lot of it very, very quality.

KELSO: Since I first started doing comics I’ve never really done any autobiographical work. I’ve always done fictional stories. And I think, for me, the reason is because, really, my influences, what made me want to write and make stories, have been prose writers. Even as a kid, I liked to make up and write stories. So when I got interested in comics, and started to figure out how to draw comics, it just never even occurred to me to do autobiographical work.

That said, a lot of when I started really looking at comics and being inspired by cartoonists, like Ellen, the great autobiographical women from Twisted Sisters, and Julie Doucet, and people like that, were really influential, but not in terms of the mode of expression, more just the art, and the general tone — and the idea that you could just draw in all these different, crazy ways, rather than that perfectly rendered, mainstream-style comics. And even — when I would look at the Hernandez brothers, even though I love their work and I admire them so much, especially with Jaime, I found his art — it looks like it was made by a machine, almost: it’s so perfect. I have to say that one of the things I loved about the underground autobio ladies was just that messy sloppiness that seemed more accessible to me, because it never really felt like I was a super-awesome drawer, even though I really wanted to make stories. And so, I looked at these women’s art and I thought, “Well, they’re managing to make it work in comics, maybe I can.”

But that never bled over into me wanting to try autobiographical stuff. But it is really interesting: I do think that if you are just thinking about women cartoonists, we are a minority. Like, some of the women that I was thinking of as you guys were talking: I was thinking about Rutu Modan, the Israeli cartoonist — I’m pretty sure most of her work is fictional. And this woman in Portland, a younger woman who I really like, named Julia Gfrörer, her work, I think, is mostly fictional. But I do think you are right, we are sort of a minority and I’ve puzzled over that, and I don’t really have a good answer for why.

VALENTI: Hilary Chute, in her book Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, she has a statement — inspired by Alison Bechdel — that comics are inherently diaristic. [“That the same hand is both writing and drawing the narrative in comics leads to a sense of the form as diaristic” (p. 10).] I’d be interested to hear what all three of you had to say about that.

KELSO: I’ll start, because I just think that’s total bullshit. I feel like comics — we’ve been fighting this battle forever about what comics is, you know? And a lot of people think comics is just superheroes, or just stupid kid strips. And I feel like what I’ve always argued, and what I passionately believe, is that comics is merely a medium of expression and there is no one form of expression that’s privileged over another in terms of making comics. And I think that one of the things that’s so fantastic about comics, is that it’s such a flexible form, and that you can do almost anything with it. It really irks me to hear somebody say that comics are inherently diaristic, and I don’t understand why someone would think more so that than prose. I mean, nobody would ever say that about prose, and I don’t understand … It just makes it, to me, sound like comics has some sort of disability, like they’re somehow incapable of expressing as wide a variety of things as prose and I just … yeah, it really irks me and I totally disagree with it.

TELGEMEIER: It could just be a case of the person who says that just hasn’t read widely through the medium …

KELSO: Yeah, but she’s an academic who’s making all these pronouncements. So it seems like she should be fairly widely read.

TELGEMEIER: You’re completely right there, that comics, from one writer to the next, is not going to be the same thing, and there’s room for so many different types of voices within it. It could just be that certain types of voices rise to the surface, as far as the public is concerned. So if you ask somebody on the street: “What are comics?” they might know superhero comics, and they might have heard of Maus, or they might’ve heard of one or two other things, but … I’m not sure where I’m going with this. I think that we’re all attracted to different things. And I like that there’s different types of writers that are attracted to the medium too. I’m happy to have everybody in this pool, personally.

FORNEY: I’ve found in doing Marbles that the form of comics was just a really great way for me to get my own story across. I think that while there’s a lot of truth to what she’s saying about it being diaristic, I know for my own self it doesn’t have to be that way. I don’t think that anybody would say that about Chris Ware’s work, for example. It’s so … contrived, and I don’t mean that in a judgmental way, necessarily; it’s very deliberate in a way that’s not spontaneous. I guess that’s the word that I’m trying to say, is that it’s really not spontaneous and approachable in the way that I would say that something else that might be described as diaristic [is]. So I think that comics has the potential for creators who are interested in expressing their stories in that kind of intimate, handwritten, immediate, approachable, a handwritten letter kind of way. Comics lend themselves to that kind of storytelling incredibly well. But comics do encompass this wide variety of styles and genres that don’t all fit into that.

VALENTI: One thing I’d like to talk about — and this is a word you’ve all used — accessibility, and style. Do you think, in general, women cartoon more accessibly?

[Pause.]

KELSO: Well, I don’t know if I can answer that fully, but one thing that I think about is that, when you see little kids with drawing and writing, it does seem like young girls are far more concerned with what their handwriting looks like than little boys. And, young boys that grow up to be cartoonists may be the exception to that. [Laughter.] In elementary school, it was almost like there was this competition to have the most beautiful, perfect, girly handwriting. And I’ve often wondered if that is connected somehow to the sort of comics and the approach to comics that women take as they become cartoonists. I think you could argue, women’s or girls’ fine motor skills often tend to develop more quickly than boys’, and so they are able to form, you know, uniform, attractive letters faster. And often — just what I’ve observed with my daughter too — a lot of girls seem a lot more interested in drawing early on than boys. But then, another generalization that I’m willing to hazard is that guys tend to be more interested in virtuosity, often, than communication.

I wonder if the stereotype of the male cartoonist with the absolutely diamond, precise style — like Charles Burns is the perfect example, clearly he developed this virtuosic approach to comics that is really separate from the drive to communicate. Because, as we’ve all established, comics work as a form of communication in a variety of drawing styles. And that you don’t have to draw in this almost machine-made perfection of the Hernandez brothers, or Charles Burns, or Chris Ware, in order to communicate, and I do wonder if that accounts to some degree to differences you see in the way men and women draw. This is a generalization, but women just being a little less concerned with virtuosity.

FORNEY: One thing that that makes me think of is Phoebe Gloeckner, because her comics work is kind of rough, you know? Bodies are distorted. And then you see her medical illustrations, or the pieces of art that she does that are kind of … just that she does in that style, are like really precise.

TELGEMEIER: Yeah, they’re totally virtuosic.

FORNEY: Exactly. And so, I imagine that that’s a choice that either comes intuitively, or she made a conscious decision to have that difference in the presentation of her narratives.

VALENTI: One thing I want to say is: when I read Chute’s introduction, I had sympathy for her because, even though I’m not an academic, I do have my undergrad degree in literature, so I could see some of her strategies to sneak this by people. I think she had to jump through some hoops to talk about what she wanted to talk about.

But, what I want to talk about with you, Raina, is she talks about — and she was focusing on five specific cartoonists, to be fair [Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, Phoebe Gloeckner, Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Marjane Satrapi] — she was talking about how a lot of women’s autobio comes from a place of childhood. Would you like to talk about that?

TELGEMEIER: Again, it’s so hard to say generally why women may, or may not, choose to do this. But, for myself, I think it comes back to what we’ve kind of been talking about as far as, you know, diarists and what a person chooses to write about. I was always a person who kept a diary. I started keeping a diary when I was 9 or 10, and really enjoyed it, and I think a lot of young girls probably write in a diary when they’re about that age and they continue to do it as a teenager, and maybe they write some bad poetry in their notebook [Kelso laughs]. Women tend to do this a lot, and I know that there are men who do too, but girls in particular; we all talk about our journals when we were young. And I think for me comics was just a natural extension of that, where I just started adding illustrations to my journals once —

[Connection interrupted.]

VALENTI: How does that inform your fiction?

TELGEMEIER: I’ve always had a really hard time with fiction. And I’ve just felt like I was a journal writer and a memoirist since I was really, really young, and so when it came time for me to try to prove myself as an adult cartoonist, I thought I had to write fiction. I thought that was the only way I’d ever be taken seriously, but I just couldn’t do it. And, in fact, in college, when I first read Monkey Food, I felt so validated. It was just like, “Oh, I can write autobiography, OK.” [Laughter.] That’s nice to know. Thanks, Ellen, for that comfort when I was younger.

FORNEY: It’s such an honor. Thank you.

FORNEY: It’s such an honor. Thank you.

TELGEMEIER: And so I started doing it short form, and then when I started thinking about longer-form stories, again, that pressure; well I’d better come up with a really good fiction story to tell. And it just never happened, and the first thing that really came out on my paper was a longer, autobio story. I think I’m just a person who is really connected with my childhood: it is really connected with my own emotions.

And so with Drama, which is “fiction,” for me that was a lot of changing people’s names, and changing a couple of people’s ages and identifying characteristics and still pretty much writing an autobiographical story, but, just putting a sheen on it, and changing enough of the details that I could step back from it. But, I still feel really connected to it in a way that’s personal. And I have a hard time with critics critiquing my work and talking about “This character is such a horrible character and here’s why,” and I’m like, but that’s me! [Laughter.] You’re critiquing me as a person by critiquing this character, or you’re critiquing a friend of mine by critiquing the character. So it’s really wrapped up in my personality and I don’t know how other cartoonists feel, but I do recognize that there have been a lot of other successes in autobiographical comics in the last 10 years or so, by women. Why is that, I don’t know.

VALENTI: I have some theories.

KELSO: Ooh, let’s hear ’em.

VALENTI: Getting into the bookstore market changed graphic novels for women in a lot of ways. I mean, the obvious way of [having another venue besides] the direct market, but most librarians are women, more women buy books, getting graphic novels and graphic works into bookstores meant there were more room for stories that appeal to women. I’m wondering to what extent it starts to influence people. So, if women did have a “literary” graphic novelist to look to … This gender thing is an issue in prose literature, too.

FORNEY: Well, Kristy, let me ask you something about what you just said. That if it sounds like there is a big … in bookstores and in libraries there are a lot of women buyers who are interested in buying women cartoonists’ books. And they’re being produced more. So, that seems like a consumer or marketing statistic. Do you know how sales statistics are for comics by men cartoonists, and comics by women cartoonists? Because from what you just said, it seems like there would be a growing number of better distributed and higher sales for women’s comics. I don’t know if I said that right, but do you see what I mean?

VALENTI: I can’t really discuss that. One thing I can talk about is BISAC [Book Industry Standards and Communications] codes. They’re marketing tools, basically: they’re keywords you can attach to a book. That’s probably the easiest way to put it. There’s a “contemporary women” category in graphic novels and comics. But there’s not a “contemporary men” category … Let’s say I was searching in Amazon: I want to read gay and lesbian graphic novels. I could pull that all up. I’ve been really fascinated by how those have changed. Because some of them are gone now, and some of them … Manga, for a long time, had a lot more categories than comics and graphic novels did.

KELSO: I wanted to jump in and mention manga because … I’m not coming from a standpoint of having read a ton of it. But it seems like it’s been really influential in the last 10 years or so in terms of bringing more women to comics. I know a lot of the friends I have who teach comics say they’ve seen this amazing shift in terms of more women in their classes, and then really starting to be a majority of women. And often they’re women who grew up reading manga. And yet, I don’t think that manga is a primarily autobiographical category of comics. I get the impression that it’s very, very fictional. There’s a lot of fantasy stories, and just genuinely fictional stories.

Perhaps there is going to be a shift when the manga generation — some of those people will probably become professional cartoonists. And one of the things that I feel we’re not talking about is that there is this whole category of comics — I guess you could call fantasy, that are fictional: Castle Waiting, Linda Medley …

TELGEMEIER: Carla Speed McNeil?

KELSO: Yeah! There seems to be a lack of prestige, or something, for those cartoonists, which is sort of mysterious. My sense is that they’ve been really successful professionally, their work sells well, and people really like it, and they’ve been working for a long time. And they are doing fictional work. And yet it doesn’t seem to have the kind of prestige attached to it that the whole Clowes, Ware, Hernandez brothers, Sacco, Spiegelman — I don’t know. Sometimes I feel like there is this desire to just see women’s work as autobiographical, and just forget about all the examples that don’t fit that category.

TELGEMEIER: I think that the next generation is already doing its thing, and they’re doing it really well, and they’re all on the Internet.

KELSO: Would you say it’s less autobiographical, Raina?

TELGEMEIER: Yeah. I think if you read comics on Tumblr, or just webcomics in general, there is a lot of stuff that’s inspired by fantasy novels, and by manga, and by watching anime on television and it’s just like a huge wide chasm that … I’m 36, and I feel like I’ve already gotten to be too old for a lot of it, but that’s OK. The people that it’s for are loving it. And they’re being inspired to make their own too. So, I think you’re talking about women cartoonists who are drawing fantasy for comic books, like Linda Medley, and Carla Speed McNeil, in my opinion, they just haven’t gotten a big distribution channel that would bring them to a wider audience. I think Finder is published … is that self-published?

VALENTI: She has it online. And then she’s been putting the book collections out in print through Dark Horse.

TELGEMEIER: I don’t know if Dark Horse has a giant distribution arm and if they’re able to get their books into every general interest bookstore. But, the potential is there for the readers. They just have to be able to get to the books in order to read the books.

VALENTI: Raina, would you say there are any women “literary” webcartoonists?

TELGEMEIER: And I wish I was the person to give you examples. I know they’re there.

KELSO: Doesn’t Kate Beaton fall into that category? Because her work isn’t necessarily autobiographical, right? And she started as a webcartoonist.

VALENTI: It’s becoming more autobiographical. Her early work is very much in the mode of humor and comic strips: the beats and the form. A lot of the early webcartoonists were very comic-strip influenced, as opposed to comic book. Which makes sense for many reasons. [Even ] just in terms of what you couldn’t do [technically].

TELGEMEIER: Most of the webcartoonists I read are doing autobiographical work.

KELSO: Memoir has been on this cultural ascent for many years, just in the larger book and literary world. I think you alluded to that, Kristy, that that’s got to have something to do with how it’s affected cartoonists. But there is this funny thing, again — I guess I’m obsessed with prestige — but the people who win the Nobel Prize for literature, it still tends to be people who do fictional work. And I think Raina, you alluded to this as well, you felt earlier in your career that you needed to prove yourself by writing fictional work: that that would make you a more mature, adult cartoonist.

I do think that it is really interesting that memoir seems to be much more popular in terms of the books that are selling. It seems to be dominated by women. And yet, in the whole book world there is still this idea, I think, that all of us are saddled with, that somehow the fictional, literary novel is the apotheosis of the most important, prestigious work being done. It just reminds me of when you think about all the people who cook food in the world, most of them are women and yet, the most celebrated chefs, the ones who are considered the artistes, tend to be men. And I can’t help but think that there’s a bit of a dynamic of that just in what we’re talking about. That the meat and potatoes of what people are actually reading tends to be more memoir focused, and written by women, and read by women. And yet the most celebrated practitioners tend to be men.

VALENTI: Yes. I keep talking about Chute’s book, but I want to talk about it because I’m happy it’s out there and she gives us a lot of things to discuss. One of the reasons why she wrote the book is they had this big piece in The New York Times, I think in 2004, and it was Clowes, Burns ... And I feel like [there are] women [who] are doing just as important work, and they’re just not getting recognized — but she also chose to focus on autobiographical cartoonists.

There’s a couple of things working here too. One thing I was thinking about was, in the ’90s, if you were an alternative cartoonist, you could be doing fiction and autobio … “alternative comics” encompassed both fiction and autobio. And now that we’re moving into the bookstore market, and beyond that into the Web, as Raina is pointing out, it changes definitions and categorizations. Do you ever use the phrase “literary comics” — is that something that comes up for you?

KELSO: I think it’s really sort of an embarrassing term because when you say “literary,” you’re puffing yourself up, trying to give yourself a bit of dignity. The way I would use “literature” is like, works of writing, or comics in this case, that have stood the test of time. Maybe were written a while ago, but they’re still important, they’re still read, and they’ve been influential. So I feel like I don’t feel comfortable calling something “literature” that was written just last year, because it hasn’t had a chance to prove whether it’s going to really have a big effect on the culture or not. So the idea of calling myself a practitioner of literary comics, it just … ughh … it gives me the heebie-jeebies.

At the same time, I definitely feel like I fit into that fiction tradition of writing on comics, more than I do, as I said earlier, than autobiographical work. But I think when you say “fictional comics,” maybe it confuses people. I don’t really feel like that’s a term that’s thrown out a lot. So then there’s of course the term “art comics,” which again I feel is sort of embarrassing to use [laughs] because like it sounds like you are puffing yourself up. So even though I don’t feel like this is a widely used term, the way I’d describe my work would be “fictional comics.”

TELGEMEIER: I run in a lot of circles with teachers and librarians who are working with young people, and for them it seems like the mission is just to convince their colleagues who don’t view comics as anything worthy, that yes, comics are literature. Yes, comics are worthy of discussion and they should count for a kid’s book report if a kid wants to discuss why they enjoyed reading a graphic novel. And so I think in the eyes of that group of people, yes, comics are literature. So there isn’t really the same divide between literary comics and whatever other kind of comics are not literary comics.

It depends on your audience. It depends on who you’re writing for. It depends on so many different things. But, I mean, I never considered myself a literary cartoonist, and yet a fourth grade teacher on Twitter will say to me: your comics are literature for my students.

FORNEY: I think that the vocabulary right now is just really screwy and not very descriptive. Personally, I think that all comics are literature. If you look at just like the simple definition of literature it doesn’t … either it’s good literature, or there’s bad literature. It just means a written work of … a written work basically. And one of the things that I think has been stumbled on, that I’ve brought up any number of times, is that the pictures in comics are part of the written language of comics and so the text is a written language, the pictures and icons, symbols, whatever makes sense to think about it, is all a written language in the service of telling a story, which is literature, and so comics is a literary medium. So, for me, comics is a literary medium, period.

But then, once you start picking it apart a bit it gets really confusing. I’m a cartoonist, but I don’t do cartoons. Kristy, I’m sure you’ve run into this any number of times, it makes for the most convoluted sentences to try to make them not sound ridiculous. Because comics is an adjective, and you know, how many times do you say comics is a literary medium … No, no, no. You have to turn things around so that you just don’t sound like you’re an idiot. Like just saying “a comic” is gonna often sound like a comedian. You know, like I don’t do graphic novels, actually, because I don’t do fiction. So, like, all of the terminology right now I think is really screwy. I’ve come to say graphic novelist, I’ve been described as a graphic novelist. The only thing that I really ask to be corrected is if I’m called an illustrator, or if the comics are called a written story and illustrations because it’s not. It’s just not that.

But so far as language being something about communicating, “graphic novels” is as close as you can get to “a book-length narrative in comic form” that most people will understand. But other than that, I think that the categories are really not very descriptive. I’m just waiting for that to change. Call it what you will, because we don’t have something standard right now that everybody’s going to understand. I think that calling it “alternative” doesn’t make sense anymore, because that was when it was mainstream and an alternative to mainstream. That’s like saying an alternative lifestyle now. It just is antiquated and it’s not useful. So, “indy” helps … what The New York Times Book Review calls the category “graphic books” which is not particularly descriptive. So, so far as the term “literature” goes, I think that comics are a literary form. So comics are literature. But the rest of the terminology has yet to fall into place as something that really communicates what it is.

TELGEMEIER: As long as people are reading them, I don’t care. [Laughter.]

FORNEY: Absolutely! And they can find them in the … oh! Oh! But this is part of what is frustrating about it. OK. So, we’re talking about bookstores and we’re talking about the different categories. One of the things that’s really frustrating for me is while I’m so glad that comics are getting the distribution that they are, and that they’re in bookstores, and that they’re in every bookstore, and they’re in libraries, but they have their own section: Graphic Novels. So my book, for example, about bipolar disorder, is only going to be in graphic novels. Which is very different from the fiction book next to it, which is different from the historical book next to it. The psychology section that has this little stack of bipolar memoirs, my book isn’t going to be there.

KELSO: Ellen, I know. That’s just enraging, because the people who are looking for your book, Ellen, it doesn’t make sense that they would go look for you in “Graphic Novels,” does it?

FORNEY: Right. No. By no means! I wouldn’t go there! What, are you kidding me? Maybe there’s a graphic novel about the troubles I’m having?

KELSO: I have a story about this very topic. I was at this library up in Snohomish County, up near Alderwood, north of Seattle, for those who don’t live in Seattle. Suburbs. And my cat was sick, he was at this veterinarian, and I had all this time to kill, so I went to the local library. It was just this local branch library in Lynnwood. And I don’t know about you guys, but I always look for my book in the library, if I happen to be in a new library. [Laughter.] And I found Artichoke Tales in the fiction section. Just filed away with all the other novels. And, you guys, I almost cried. It made me so happy. I had never, ever seen that before. And I actually went up to the circulation desk and I said, “I am so impressed with you guys that you are filing the comics in with all the other books, I’ve never seen that in another library. I just wanted to congratulate whoever made that decision.” [Laughter.]

The librarian who was at the desk, I don’t think she was connected to having made this decision, because she just looked at me like I was fucking crazy. [Laughter.] But you guys, it was the most gratifying experience I think I may have ever had. To have just seen my book where I’ve always felt like it belonged. It’s so fun.

FORNEY: Yes. Yes, yes. Well, congratulations. That’s awesome.

KELSO: Thank you. [Laughs.]

VALENTI: Raina, you work with Scholastic, and your audience has a lot of younger people in it who don’t have these preconceived notions. So how does that affect it?

TELGEMEIER: I’d say that 75 percent of my reviews start out with, “Well, I don’t like comic books, but …” So this is coming from readers who have either never read one before, or have just a preconceived notion of what “comic book” or “graphic novel” means. And then they say, “but it was good,” “but I really liked it,” “I actually liked it.”

It’s nice to be part of a generation who’s redefining what sequential art can be for readers. I get a lot of reluctant readers too. A lot of emails from kids and from parents who are both just jubilant that the reader has finished their first book, or voluntarily picked up a book and wanted to sit down and read it. It’s just really common for kids. Especially when they get to be 8 or 9 or 10 years old, when it’s expected that you’re going to be an independent reader at that time in your life. But a lot of kids just aren’t.

It’s nice that a graphic novel can fill in that gap for them, and let them feel good about reading something. And that might mean that they become a reader of prose too, it might mean that they become somebody who’s just interested in reading more graphic novels. But it’s really been a gratifying experience for me. I was not a kid who had any problems reading. I wasn’t a reluctant reader. But I did start reading comics when I was about 10, and they meant so much to me at that time. And I’m sure that’s just kind of what’s happening here too and it’s wonderful.

FORNEY: One thing to piggy-back on that: reluctant readers, or young readers that have a hard time, is something that I found after The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian came out, which is a book by Sherman Alexie that I collaborated with him on — where the main character was a high school boy who was a cartoonist. And so I was the cartoonist aspect, and I did a lot of comics for the book. I was going and giving talks at a number of different places. Several times ESL students that came to me and said that the comics helped them read the book, and know that they were understanding it.

That’s part of the universal aspects of the language of comics, the visual language, and the language of icons. Saying that it’s a universal language sounds like an overstatement. But if you think about the kinds of instructions that are all around an international airport in order to throw away your garbage in the right place, or how to get out some emergency exit, there are essentially little comics all over the place with no words, because they have to communicate to all different kinds of languages. And so that’s one of the many different kinds of strengths that comics have as a storytelling … as a literary medium that is readable by lots of people, who read in very different ways.

Transcribed by Lucy Kiester and Daniel Johnson.