Time was, Alex Robinson virtually disappeared between projects. His career-defining graphic novel Box Office Poison originally came out in individual-issue form from Antarctic Press, and Top Shelf only published the collected volume in 2001, once the series wrapped. But after that initial book, he moved away from the serialized form. His subsequent books have all debuted as completed graphic novels, and while some of them are short side projects (2003’s BOP! More Box Office Poison; 2007’s wordless mini-fantasy Lower Regions; and 2009’s A Kidnapped Santa Claus), 2005’s Tricked and 2008’s Too Cool To Be Forgotten are both substantial works that required significant time investments. In the past, Robinson was relatively quiet about works in progress until they hit bookshelves, which sometimes meant fans barely heard from him for years at a time. That was common enough for creators in an era before social media fully took off, but Robinson’s work process — writing, penciling, and inking all his own pages — made for long periods outside of the public eye.

But his Internet profile rose considerably once he entered the podcasting world. The humor podcast The Ink Panthers Show!, with Mike Dawson, launched in 2009. In 2013, Robinson and Pete “The Retailer” Bonavita started Star Wars Minute, which continues to analyze and discuss the Star Wars films one minute at a time. And in 2014, Bonavita, Robinson, and two other friends started AlphaBeatical, which looks at The Beatles’ catalog at a rate of one episode per song. Promoting the podcasts and interacting with fans seems to have drawn Robinson out into regular social-media excursions, including posting sketches and side projects to Facebook, and pages from a work in progress, Career Killer, to his Tumblr.

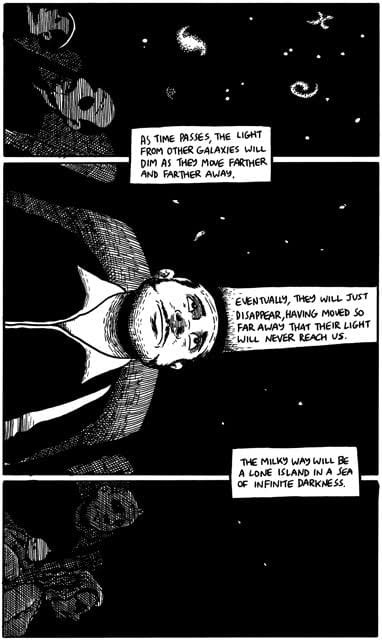

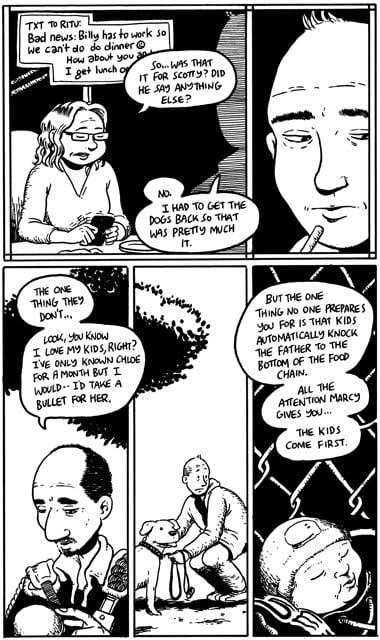

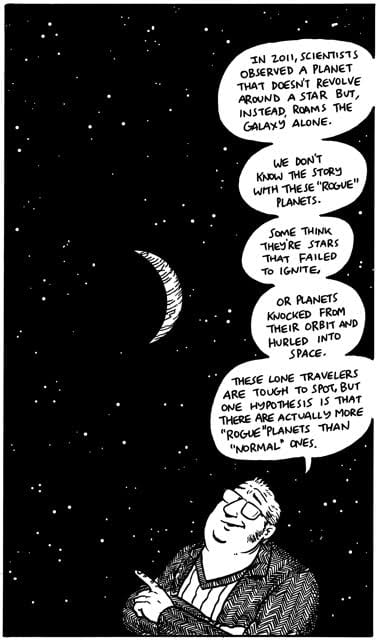

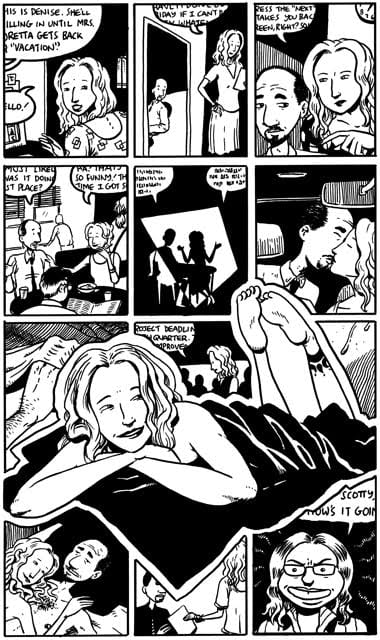

Still, he’s more protective of his main work, and even his fandom was a little surprised at the end of 2015 when he suddenly announced the upcoming release of a new 256-page graphic novel, Our Expanding Universe. Like Box Office Poison and Tricked, it’s a slice-of-life book that explores a cross-section of friends, acquaintances, and lovers, each living through their own personal crises and not entirely appreciating the struggles other people in the story are going through. Universe’s primary characters are three aging friends who are growing apart: Scotty has a toddler and a baby on the way, Billy and his wife are trying to conceive in spite of his doubts about fatherhood, and Brownie is an acerbic confirmed bachelor with no use for children. At least two of them feel pangs about the way their friendship is eroding, and all of them are coping in different, sometimes destructive ways. Robinson tells their story through low-key conversations and his familiar story sprawl, which takes in conversations between their wives and family members, video game sessions and bong hits, and a planetarium trip. Along the way, he uses a scientific metaphor about the universe’s steady expansion as a metaphor for the way maturity and families are pulling these friends apart.

Shortly after Our Expanding Universe was published, I talked to Robinson (no relation, it’s a common last name) about the new book, his podcasting empire, what killed Career Killer, and how his work methods haven’t changed substantially since the 1990s.

TASHA ROBINSON: Let’s start with the book’s central metaphor, the idea that the universe is expanding. Was that always part of the story, from your original conception?

ALEX ROBINSON: As far as I can remember, it was always part of the story. I’d been kicking around the idea of the main friendship storyline, and how adulthood could impact it. I had also really gotten into astronomy, and I was watching an astronomy documentary about how dark energy was making everything expand and move farther apart. I thought, “That seems like a good metaphor for what I’m trying to convey.”

But you were also personally experiencing this moment where you and your wife were getting to the age where you had to make a final decision about whether you were going to have kids. How did you decide to do a book about that question?

I had a group of friends, and we were all pretty tight, and the next thing you know, everybody started having babies, and everything just kind of splintered. As happens in life, our circle of friends broke up, or at least got distracted by real-world concerns. So I figured, what better art therapy in dealing with this than to do a book about it? My wife and I never intended to have children, so for us, it wasn’t really a matter of wrestling with that angle. But I had to put myself in the shoes of someone who was going through that, just for the sake of the story.

My husband and I never intended to have children either, but when our friends all started doing it, we hit a point where we stepped back and said, “Are our younger selves making decisions for our older selves? Do we need to re-examine this question?” Did scripting these characters’ arguments for parenthood give you any pause? Did you personally feel any impact?

No, I was a bit more on the fence. If my wife had really wanted to have kids, I probably would have gone along with it. But it wasn’t something I wanted to lobby for, and she really had no interest, so it wasn’t a discussion in our house. But watching my friends go through it… I guess I don’t really understand the appeal of children. In a way, I was trying to figure out what my friends were thinking. Like, why would they want to wreck everything? [Laughter.] Everything was going so well! We hung out all the time and had fun. Then next thing you know, everyone just loves to baby-talk and discuss diapers and stuff. So I think it did help in that regard.

When I first started the book, it was really going to be more of a vicious satire of what parenting looks like from the outside. But when I’m writing a book and working on it for a long time, I can’t help but get sympathetic to the characters. Even if I disagree with them, just writing them is enough to make me… In order to convincingly put across the argument, and make these characters realistic, I really have to think like them. So I toned down the angry part of the book. It got narrowed down to the one character who is very vocally anti-child, or at least anti his friends having children.

Did you consult with your friends with kids to get their perspectives? Is Scott in the book channeling anyone in particular?

No, it was just careful observation of my friends. There was a time when I tried to formally say, “Tell me what it’s like being a parent.” But as I relayed in the book, it’s very hard to convey without—it’s like romantic love. How do you convey the emotions behind it without lapsing into Hallmark card cliché? I knew my friends weren’t going to help in that regard if I just literally interviewed them. So I had to kind of piece it together for myself. Also, this is going to sound very either sad or amusing, but when I started the book, we’d recently gotten a dog. I’d never had a dog before, and the level of attachment I felt to the dog was much more than we had to our cats. So it made me think, “Having a kid must be like a dog, cubed.” I love my dog, and get very upset when he’s sick, and all sorts of stuff. I can only imagine what it’s like having an actual child. Imagine having a dog that would eventually be able to talk to you, and eventually become a Supreme Court Justice or something. The dog really helped.

There is no one-to-one correlation with me or any of my friends. I jumbled everything up because I didn’t want my friends to get mad. [Laughter.] I made up characters and distributed some qualities of my friends. And there’s no one character that is me. I use the Brownie character to express my more cynical anti-child views, but he’s an extreme caricature of that aspect of my personality.

Box Office Poison and Tricked both have characters visually based on you, but they don’t seem to reflect your personality. Do you still find it fun to physically put yourself in your books?

I did put myself in the background of one panel in Our Expanding Universe. I put my wife in the background. People who know her can see her in other books, but for some reason, I didn’t do that as much with this one, I don’t know what the explanation is. I don’t know whether that was unique to this book or whether it’s something I’ve sort of moved beyond or whatever, but I don’t know. Your guess is as good as mine.

I noticed Garfunkel and Oates in the planetarium scene, which I don’t think I would have caught, except that Riki Lindhome’s eyes are so distinctive.

Yeah, she’s hard to do a good caricature of, but yes, good eye on that one. To you for seeing it and good eye for me for being able to do a convincing caricature.

Are there other Easter eggs people should particularly watch out for in the book?

I put Brian May from Queen in the background of the planetarium scene because after Queen broke up, he went back and got his doctorate in astrophysics. I put a lot of astronomy names in the book. If a character’s named, or if there’s a proper name anywhere, there’s a good chance it has something to do with space somehow. Like when Brownie goes to the planetarium, he meets his friend Herschel, and William Herschel was a famous astronomer. Originally Herschel’s name was gonna be Hawking, but a friend said Hawking was too famous, and it would be distracting.

Herschel becomes your voice for the inter-title insert panels in the book, about the expanding universe, which Brownie clearly sees as an emotional metaphor for what’s happening in his life. But outside of his reactions, those science-fact pages don’t often seem directly related to what’s going on in the story. Are they extending the metaphor? Are they just fun science facts?

They’re supposed to have some metaphorical connection to the book. I didn’t want to underline it too much. The pages were consciously put in specific places — well, it was kind of a mix. When I was laying out the book, I started each chapter with the first page on the right side. Occasionally, though, I would have a gap where the previous story ended, and I had an empty page there, so I used those to put these space-factoids in and underscore the overall astronomy metaphor. So they’re supposed to have specific connections, but I’m glad they’re not super-obvious. I guess it’s always better to be subtler than too obvious.

Your books are always a long time in process. How long was the gap between “I’m doing this book” and it hitting shelves?

It’s hard to say. My last book came out in 2009, so it’s been six years, but I wasn’t working on this all that time. I had started another project that fell apart, and I had a distraction where someone wanted me to be a collaborator with them: They had a script, and they wanted me to draw it, and I started on that, and then that fell apart. I probably wasted two and a half years on projects that didn’t come through, so I’m gonna say at least three years maybe. That sounds about right.

The project that fell apart, that was Career Killer? What happened with it?

Yeah. I was working on a book prior to that—I had done Too Cool To Be Forgotten, and at one point I hit a rut with that, so I did this Lower Regions story, which was just fun to draw. There’s no dialogue, it’s just straight-up pantomime adventure. I had so much fun doing that, I was just like, “That’s it, no more people sitting around talking about their feelings. My next book is going to be a fantasy D&D type book.” Like most of my books, I set out with a vague idea and just started improvising from there. I got about 80 pages in, complete penciled and inked pages and everything. This one had dialogue.

And I just stalled out on it. I realized I don’t read fantasy novels, and I have a hard time taking it seriously enough to write a legitimate story about it. I could write the other story because there was no dialogue. It was very simple. The protagonist fights a monster, kills the monster, moves on to the next one. But any time I started having dialogue and characters, and “Okay, what’s this character’s motivation, and how are they relating to each other,” the whole thing just fell apart. It really rattled my confidence. I think that made starting another book extra difficult: “Oh my God, what if I start working on this and I flame out again?” I think that slowed me down at first. There came a point where the story kind of clicked, and I worked a little faster after that, but I was very gun-shy at the beginning.

Eighty pages is longer than Alex Robinson’s Lower Regions in its entirety. Can you see doing something with those pages someday?

Well, the thing is, it’s 80 pages, but the story barely starts. I was at the part where they’re at the tavern saying, “Oh, let’s go on an adventure.” It’s not a matter of, “Oh, I only have to do another 50 pages and it’s done.” I was maybe 4 percent through it. So it’s unlikely I’ll ever go back and do that. Some people have suggested I should make it an open-source thing, where I say, “Okay, anyone who wants to take the story from here…” You know, I hand it off to someone else, and they either do another 80 pages or finish the book. If someone wants to do that, they should feel free to contact me, but I certainly wouldn’t want to wish that on anyone. I feel like this fantasy thing is going to be like my white whale, or Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Every time I try this, it does not seem to pan out. So I’ve learned my lesson, hopefully.

Wasn’t there a point where you were posting a page a week online, webcomic-style, and interacting with fans around it?

Yeah, after Career Killer fell apart, I said, “Okay, maybe I’m putting too much pressure on myself with this huge epic.” So I started doing one-page chapters, and the idea was that I would post them on the Internet. I tried to make it easier on myself—or harder on myself, depending on how you look at it—by only drawing the pages that were fun to draw. I would not do pages of exposition. I heard a story about Image Comics, back when they first started, that Rob Liefeld or somebody had a technique where, because he got so much money for his original art, would sit down and draw five big splash pages of just like, the main character fighting a robot dinosaur, the main character fighting a ninja, two space-Nazis fighting each other. And once he had five of those, he would sit down and say, “Okay, what story can I do that would tie these five pages together?” We all sneered in art school like, “Can you imagine? What kind of artist does that?” But now that I’m long out of art school I’m like, “That sounds like a really fun way to do a story.”

The second attempt at that fantasy thing I was posting was trying to do something along those lines. Only drawing the fun stuff, and not worrying so much about the plot. But I got bored with it, or started overthinking it again. The writer part of my brain kept elbowing his way in, saying, “How is this going to tie into this other scene you did?” And so on. So I once again abandoned the story, bringing the total to about 100 pages of unusable material.

Five years ago, The Comics Journal posted an audio interview with you where you talk a lot about how you disappear for years and don’t expose your work-in-progress. The webcomic model has become so common as a way to build fandom while a graphic novel is in development, but in the past, you’ve preferred to do the work privately. Did the experiment of interacting with fans around the process change how you work at all?

My work—up to this point, anyway—isn’t necessarily conducive to reading one page a week. I think for better or for worse, I’m out of step with the webcomics world. My stuff tends to be very talky and character-driven, so I don’t really feel like it’s well suited to one page at a time. I’m more interested in the idea of serializing either in floppies, or maybe digitally releasing 20 pages every two months. It’s a double-edged sword: The hermit style of retreating and doing it in private, I find it very enjoyable, and I can get more lost in the work, as opposed to the constant, “Oh, are people liking this? What are people saying about it?” That has its own hazards, though. With my next book, I think I’d like find more of a balance between serializing and having that lost-in-your-own-work quality. It’s tough, because it’s been six years since my last book. I feel like a lot of my audience kind of dribbled away. There are college kids reading now who’ve never heard of my books and don’t know who I am. So that’s both liberating and frustrating that lost momentum, publishing-wise.

At the same time, you’re doing multiple podcasts, which have developed their own fan base. Have they satisfied any itch for a regular conversation with fans? Or created one?

It definitely satisfied an itch, because comics is very lonely work, you know? I work at home, and I’m just working by myself a lot of the time. Doing the podcasts with Pete, getting to talk to him, getting to interact with fans, is definitely a positive aspect of the whole thing. I think a lot of people who listen to the podcast were totally unaware that I was a cartoonist, or are only peripherally aware when I mention it. That’s kind of funny, that I’m more popular as a podcaster than a cartoonist at this point. [Laughter.] Hopefully this new book will turn things around. It’s definitely nice having more social interaction. The podcasts are, by nature, a lot more, “Post it on the Internet, are people liking this? What are people saying about it?” As opposed to the comics, which I’m like, “I need some time to percolate these ideas.” It’s a delicate stage, when you’re in the actual creating process, to put stuff out there. It can really affect the outcome of the book. Chester Brown’s Underwater is a famous example. If he had done that as one big book, we would have it, but since it was serialized, it died in the cradle. We never got to see how that was going to pan out.

It’s interesting that you describe yourself as a cartoonist, rather than a comic-book artist, or a graphic artist, or just an artist. Does that word carry any specific weight for you?

Graphic novelist sounded pretentious to me. To me, cartooning is a proud tradition. A lot of brilliant people were cartoonists, so it doesn’t bother me, the word. I’ve never gotten bogged down with what term to call something. “Cartoonist” a) sounds fun, and b) I think is an accurate description. I don’t know, is it not politically correct to call yourself a cartoonist? Does it carry an inherent element of not taking itself seriously?

Well, self-applied labels seem to be the most meaningful ones. You’ve often been asked whether you’re a writer who draws, or an artist who writes. You’ve consistently said you’re a writer who draws. Is that a meaningful question, or just somebody attempting to slap yet another label on you?

It think it’s useful in the sense that you can get how creators approach work, whether they’re more visually driven or story-driven. I think I’m more story-driven, driven by the dialogue. But I want to let the artist part of me be in the driver’s seat for a while. I’m really struggling with how to do that. How do you tell a story without getting bogged down with the words? [Laughter.] That sounds idiotic when I say it. But it’s a visual medium, and it just seems like a lot more fun, at least at this point. So yeah, I guess the writer-who-draws thing still applies, but I’m working on it.

“How do tell a story without getting bogged down in the words?” is a really interesting question given Our Expanding Universe’s focus on conversation. You pay attention to the small details of conversation in a really unusual way. Like before the big fight in the fast-food restaurant, you take the time to show the characters individually ordering, and interacting with the counter girl. How do you decide how granular to be with these mundane, day-to-day exchanges?

It’s really a gut thing. I have a rough idea where the chapter’s going, “This is the chapter where they’re going to have a big argument” or whatever. But I take it like in real life. “If we were in a restaurant, we’d be ordering food.” I don’t really have any conscious editing process in that regard. It’s really like improvising. Musing.

You’ve said your books tend to be improvisational. But I’ve read that you pre-scripted Our Expanding Universe in advance much more than your other work. Is that true?

Yeah, like I said, my confidence was really rattled after that fantasy book didn’t work out. So I really wanted to make sure if I reached a point where I was like, “Oh my God, I don’t know what happens next,” I would have my index cards to fall back on. I plotted out the key scenes on index cards, saying, “Okay, this is where somebody gets pregnant, this is where this happens…” I had rough sketches so if I got writer’s block, I could skip ahead and work on a different part. Thankfully, I never really needed them, but having that insurance policy made me feel a little more at ease, and kind of freed me up. Weirdly, the next book I’m working on, I’m doing even more preparation for it. So who knows how that’ll pan out? Will it get to a point where I prepare too much, and there’s no fun left in the actual creation of the book? We will find out.

Speaking of having fun, you’ve said just drawing people standing around talking isn’t that enjoyable. Is the solution that sequence in the book where Brownie and Billy are playing video games while they’re having a heartfelt discussion?

It’s a solution. Those pages were a lot of fun to do. I can still do people talking about their feelings without—there are other scenes where people are talking, and there’s literally just talking heads and minimal backgrounds. That’s another solution, to cut down on the backgrounds. There are a lot of things in the book that are, “How do I make this interesting to draw?”

It’s visually exciting, but the juxtaposition between these crazy images and the naturalistic conversation is also compelling. And then they’re having this talk that’s key to their relationship, but Brownie keeps interrupting to say, “Grab that hammer.” It feels improvised and in the moment. How much flexibility do you actually have when you’re actually laying out a page if you aren’t doing that much pre-scripting?

I write out the dialogue in my sketchbook. Once I feel like I have about a page’s worth of dialogue, I lay out the page, usually just a rough sketch. With those particular pages, they wouldn’t have any of those asides, it would just be the main dialogue. But then once I start roughing the page, I’d say “Okay, the video game character’s doing this,” and add dialogue.

Are you working with pen and ink, or doing these digitally?

It’s all pen-and-ink. It’s all old-school. The original art is not that much bigger than the printed pages. The only concession I made this time around was doing the corrections digitally, which is a lot easier than Wite-Out. Other than that, the pages look exactly how they’re printed. I fill in all the blacks, and so on. I really would love to learn how to do stuff digitally, but I feel like the learning curve is such that it would take me 10 years to be get to the point where I would be willing to show the art to the public. Do I want to spend 10 years learning how to draw digitally, or should I spend 10 years working on two more books in my old style?

Has that part of your working method changed significantly since Box Office Poison?

No, it’s almost exactly the same. I draw smaller than I used to. I’ve changed pens every now and then. But for the most part, me of 1987 would understand how to use all the tools I use for the way I work now.

You’ve done so little work with color. Some of your Star Wars Minute art is in color, and you’ve done covers and side projects for other people, but your books are black and white. Why is that such a strong impulse for you artistically?

I don’t think it’s so much an artistic impulse. It’s more the fact that I can do it all. I would not be able to color my own books. I just don’t have the skills to do that. It would take a thousand years. I think part of what drew me to comics a long time ago was that I could do everything. I could pencil it, I could write it, I could letter it, I could ink it, if necessary I could publish it, and when I was finished on the drawing table, that’s pretty much exactly the way the page would look. I had a sense that I could control everything about it.

I think I’m at the point where I would like to do color stuff. For some reason, looking at my stuff in color on a computer screen is almost like looking at it in 3-D. It just adds a whole ’nother dimension that I would really like to try. But then I go back to the problem of how do I go about coloring it? Do I pay someone who would probably make more money from coloring it than I would get from publishing the book? I mean, somebody must have figured this out—there are a lot of colored books out there, so somebody must know an economically viable way of doing this.

And you’re still hand-lettering? The difficulty factor on that just seems so high compared to digital.

Maybe looking at my lettering, you can see I don’t really spend that much time thinking about it. Like I said, I do one page at a time, so I basically would letter one page and then pencil and ink it. It’s not like I’m sitting, doing the whole book in one shot. It’s just the way I’m used to doing it.

I’m surprised you don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it. It’s one of the many really distinctive things about your art. I’ve read that Dave Sim was a big influence on you in a lot of ways, but that’s where I see the influence most, in the way you convey anger or coldness or frustration in your lettering and your word balloons.

Yeah, definitely Dave Sim was an influence on my comics creation. I’ve just never been a fan of computer lettering. You’re taking a tool out of your toolbox to convey to help your story. If the characters are going to be exaggerated and cartoony, why wouldn’t you then also use cartoony lettering? Maybe not to the extent that Walt Kelly did, but it’s a method of characterization, to convey more information that you can do with computer lettering. Or at least, people aren’t taking as much advantage of computer lettering as they can. It certainly makes corrections a lot easier, though.

Just flipping through the book, I’m struck by how diverse the page layouts are. There’s no grid, no standard page, no default. Do you flip back through the book as you go to make sure you never repeat yourself?

I don’t go back. There are certain layouts I’ll repeat. I just hope people won’t notice it as much if there’s a lot other stuff going on. I don’t know why I’m thinking “Oh, I can’t use the same layout on two different pages.” In my head, my default is a six-panel grid, three tiers of two panels each, but I always try to mix it up, because I know it’s more visually interesting. Because my stuff is so dialogue-driven, the dialogue sets the tempo for the story, so conveying a story in a six-panel grid is different timing-wise than a different layout. I’m just trying to keep it visually interesting. Just approaching each page as its own thing. Certainly people have done interesting work with rigid grid limitations, but it’s just not something I’m interested.

Which comes back to keeping it fun for yourself. Does the diversity of your characters’ faces and bodies fall into that same category? Are you trying to reflect real body diversity? Is it more about keeping yourself from getting bored?

I think it’s more the latter. I’m interested in depicting people as relatively realistic, and showing what regular people look like, as opposed to idealized bodies. And it’s a way of making it easier on the reader, because you can always tell who it is. It’s easy to differentiate the characters. Matt Groening had a good formula: If you can show the characters in silhouette and still tell who is who, that’s a good element of character design. I wouldn’t say I take it to that extreme, but I do try to make the characters diverse so you can always tell who’s on the page. Although looking through the book, I realized I give three of the minor characters the exact same parted-in-the-middle, big-forehead hairstyle, and I’m kicking myself for that. Can’t win ’em all.

Speaking of which, so much of your work is about things falling apart over time, a feeling of “the center cannot hold.” Why is that such an theme for you?

Huh, you know, it never even occurred to me that that was a theme, but it doesn’t surprise me. My parents got divorced when I was a kid, maybe that’s an element to it? I mean, to me it just seems kind of obvious, “Well, duh, eventually everyone dies, everyone leaves,” and so on. Maybe that’s ultimately the impetus. I’d like to think that the lesson is to enjoy life while it’s around. In a sense, knowing this will all eventually end should, like that old cliché, really make you appreciate the day-to-day pleasures of life, the little things. I’m a pessimistic person by nature, so that doesn’t surprise me.

Do you think of your work as having messages or lessons? Things you want to actively communicate to readers?

Not consciously. I think I’m more trying to communicate with myself. Ultimately there’s a selfish motive. I’m trying to work through my own thing. If other people find it useful or entertaining, super. I think the main reason I’m doing it is as art therapy. So I can see themes in my books that other people who aren’t inside my head all the time might not pick up on, obviously, because I’m in it a lot more. It’s funny, I was looking through this book—I finished the book a year ago, and it took a while to come out—I was just rereading it and picking up on things I did not consciously intend, like, “Oh, that scene echoes this scene, or foreshadows the scene that’s going to come later on. I was very pleased that I had that stuff in it without realizing it, and that I was able to reread my own work, because normally I cannot stand to read my own work. All I see are the mistakes.

I actually reread all your books for this interview. And one of the things that most struck me is that when I first read Box Office Poison 15 years ago, I really empathized with Sherman and where he was in life. Now, he feels like such an asshole to me, with his boundless contempt for his job and his customers. You wrote Box Office Poison as a twenty-something writing about twenty-somethings. You wrote Our Expanding Universe as a forty-something thinking about forty-somethings. Have your characters changed for you over time, as your own perspective on life has changed?

Hmmm, that’s a good question. Box Office Poison continues to be my most popular book, and I’m pleased people enjoy it, but it also feels like it was written by a totally different person. It’s funny that you mention Sherman, because by the end of the book, I pretty much came to agree with your feelings that Sherman had problems. That’s why the emphasis of the book shifts over to Ed for the second half, because I found Ed to be much more of a sympathetic character who was capable of growth that I didn’t see in Sherman.

People always say, “Are you going to do a sequel to Box Office Poison? Are you gonna show what the characters are up to?” I’ve thought about it a bunch. But I just can’t relate to the characters any more, or project where they would be, other than hints of what I imagined their lives would be. Yes, as time goes on, I do see the characters differently. It’s strange to me—I thought Steven in the first story was 30 or something, much older than the other characters. And now he’s so much younger than I am. It’s a peculiar phenomenon.

Sometimes I look at the old books and I get a bit lost. I’ll start rereading them and occasionally make myself laugh with a joke I made or something. Inevitably, I hit a part where I’m like, “Ugh, that was a clunker” or, “Ugh, that drawing doesn’t look quite right.” That’s when I have to put the book down. Occasionally, I just worry that I’m going to unconsciously repeat myself. I’ll come up with a good joke and I’ll be like, “Wait a minute, did I do this joke in Box Office Poison already? Is that why I’m so sure about it?”

That self-deprecating attitude has dogged you throughout your career. When you were drawing yourself in books, you always made yourself fat and sweaty, which you eventually comment on in Box Office Poison. And then you actually had a self-deprecation jar you paid into when you rag on yourself during that Comics Journal panel. Is this something you’ve been fighting your whole career? How conscious are you of it?

I wouldn’t say I’ve been fighting it. I’d say I willfully surrendered to it a long time ago. A friend of mine said heard an interview with me and said, “Don’t be self-deprecating. It’s unappealing.” I do try to fight it. I guess the mindset is, “I’m going to put myself down before you can, to show you I’m aware of my own flaws.” It’s ridiculous.

Box Office Poison and Our Expanding Universe both have so many minor characters and side stories that invite expansion. In Our Expanding Universe, there’s a brief scene about Gina, who’s just gone back to a physically abusive partner, and is defending him to her girlfriends. It seems like such a powerful story for a side moment. Are you planning anything more with it?

I never planned to do anything more with it, but I do agree with you. I was really on the fence as to whether to include that chapter. I almost took it out of the book for the reasons you mention. Is this really the kind of thing to bring up as a footnote? I asked my editors at Top Shelf, “Do you think I should cut this?” and they didn’t seem to think it was too egregious. I’m not sure it was the right decision.

With Box Office Poison, when I do look back at it, the impression I get is of someone who’s like, “Oh boy, I’ve been given my own comic book! I’m going to put everything into this book that I’ve ever wanted to do!” Stuff that now, I would be like, “That subplot should be taken out, it’s kind of irrelevant.” I think the storyline with Gina was along those lines, where I was just like, “That could be interesting,” but being unsure about how it fits into the larger picture. Now I’m talking myself out of it. [Laughter.] It’s out there.

You’ve always had a strong voice in terms of female characters.

People have said that a lot. I’m happy that people are pleased with it, of course, but to me, it’s always seemed like, “Why wouldn’t you at least try to incorporate different voices?” As I was doing the book, I was self-conscious about the fact that it’s three main guys, and the women in the book are in their orbit. Given the story I wanted to tell—I think you could just as easily tell that same story with three women as the centerpiece, but I don’t know how convincingly I could do it. I would love for someone else to do it, because I would love to read it. There’s a line between pushing yourself as far as you can to put yourself in other people’s shoes, and actually doing a convincing version of those characters. I don’t know if I could have pulled it off.

One of the most surprising things in the book is Brownie’s stance against sleeping with a married woman. Giving that he’s such a selfish hedonist in other ways, and so uninterested in marriage and family, this moral belief is an interesting facet. What did it mean to you?

I didn’t want part of the story to be, “Is Brownie going to wind up in a relationship like the other characters.” I wanted Brownie to be alone, without the suspense of, “Is he going to wind up with this girl?” I could see myself going down a road where they would meet, and she would become a big character, and it would have derailed from my main point, so I nipped it in the bud. Originally, that plotline was going to be bigger, but I think it gives Brownie a bit more depth, as opposed to him being a more caricatured Quagmire-type character. People in life generally can surprise you with things they care about or don’t care about, or the moral choices they make.

You’ve said before that using pop culture in stories can be a trap, because it ages the book faster. Here, the characters experience a lot of pop culture, but it’s largely invented for the book. How did you want to approach pop culture here as a major part of their lives.

This time around, I apparently completely forgot about my edict, because I refer to Aimee Mann and Adventure Time.

And The Wire.

Yeah, so apparently older Alex is feeling free to ignore younger Alex’s rules. There wasn’t as much of a conscious plan in this one as in Box Office Poison, but maybe it’s just because my life is less pop-culture-driven than it was when I was 25. So there wasn’t much conscious strategy, expect the video games are all made up because I don’t know anything about video games. I was also secretly hoping, of course, that Aimee Mann would find out I referred to her in the story, and that she’ll want to come over and hang out and become friends.

So how do you answer the question you pose in the book? Would you play her music in the background when you were hanging out with her?

I don’t think I would. I think I would be too self-conscious. When her song came up, I’d be looking at her like, “Does she like it, does she like it, huh, huh?” I think I’d put on… I don’t know. We’d meet somewhere else so I wouldn’t have to worry about the playlist. That’s my solution.

You’ve said your next book is going to be a lot more consciously about space?

Yeah, I’ve been reading a lot of Jim Starlin. But I’m thinking more cosmic. The catchphrase I’ve been using for it, which is probably helpful to nobody, is New Gods meets August: Osage County. The problem with that is that people who know who the New Gods are probably don’t know what August: Osage County is, and vice versa.

I know both of those things, and I’m horrified.

You’re my target audience, right there. Yeah, it’s kind of a mythological, cosmic epic, but with a fighting family at the core of it.

Are you evoking Starlin’s art?

Part of the reason I want to do a space thing is that, again, it would be more fun to draw, and having characters flying around using superpowers seemed like a good compromise. Almost like a video game aspect. Fusing the two things from Our Expanding Universe, with the people having conversations while playing video games, into one thing, with the characters having conversations as they do superheroics. At least that’s the plan! Hopefully five years from now, you won’t be asking me, “Whatever happened with that Cosmic Saga book?” and I’ll be like, “Oh it didn’t work out. I got 100 pages into it and it fell apart!”

Are you approaching it with that same level of pre-planning rigor to hedge against that happening?

I’ve basically been spending the past year hammering out all the details, and trying to have as much of it plotted out as possible. And I’ve been thinking about working in a different technique. Like more the Marvel style of writing out a plot, then penciling it, then going back and putting the dialogue in, which would be a radical departure from the way I normally work. I’m trying to shake things up. I’m definitely putting a lot more planning into this one, probably more than I have any of my books. We’ll see what happens.

Are you planning to disappear for a few years again and pop up with it finished?

No, this is something I think could lend itself well to serialization. To coming out in digital chapters, or floppies, or something along those lines, depending on what the publisher wanted to do. I’m open to a regular release schedule. I don’t have a publisher at the moment. I want to get it well on its way before I start shopping it around. I’m really excited about it, and if I shopped it around to publishers and they said, “Uh no, we’re not really interested,” I’m worried I would lose my steam on it. I’m really determined to do it, so I don’t want to get rattled. And I want to be at least halfway done before I start serializing, so I don’t have to worry about the deadlines looming. I’m guessing it will probably about 300 pages. I can’t give a timeline as when it would be actually be released. If it’s going to be serialized, it would start coming out sooner rather than later. I want to have as much of it plotted out as possible so I can hit the ground running and really get it out there.