[For part one of this interview, please go here.]

You write in the Neil anthology book about how you left comics, or rather, how comics left you. Do you want to talk about that?

You write in the Neil anthology book about how you left comics, or rather, how comics left you. Do you want to talk about that?

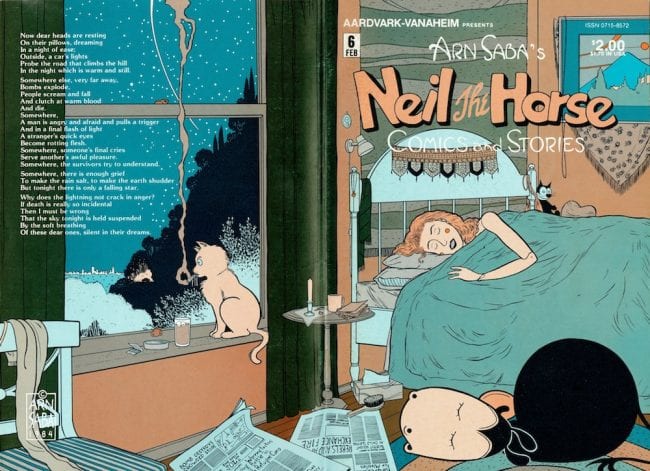

It’s an important part of my story. The six-page essay in the back of the book is the first time that I’ve had the opportunity to put that information out there. A lot of people who I knew in comics have never known the story. The thing is that I don’t exactly know what happened. I know what happened to me, but I don’t know why. I have my own theories. I was going along and getting attention and getting published and things seemed to be going well. In 1993, I was working on a graphic novel. In those days you didn’t have to do much to call it a graphic novel. As long as it was longer than thirty-two pages, it was a graphic novel. I was working on this long comic book, shall we say. In the meantime, it’s hardly a side story, but after a lifetime of not being very happy about being a man and realizing that I should have been female it finally came to the point where I realized that I could do something about it. And I couldn’t live any longer being somebody who I really wasn’t. The transition takes time, so from 1992 to late ’94 I was going through the process, but in mid-1993 I had to announce to the world – or to anybody who was paying any attention – that I was going to start living as Katherine. So I came out and started being Katherine – and that was the end of my career.

Whether that was the reason, I don’t know, but the two things happened almost simultaneously. Within a couple of months of my first attending San Diego in ‘93 as Katherine, nobody would even talk to me. They would if I walked up to them and spoke to them, but afterward I would send off letters and emails and would phone and leave messages and I would never get answers. I’m talking about publishers and editors, not my personal friends. I was suddenly persona non grata. It didn’t occur to me then that it was because of my transsexualism. I don’t know why I didn’t think that. [laughs] Maybe because at that point I was living in San Francisco. Instead, I thought that I had been judged to be a terrible cartoonist who nobody in their right mind would want to publish. I’ve since been told that at that time the comic book business was going through a financial retrenchment and a lot of publishers were having trouble staying in business – and a lot of them didn’t stay in business. The industry became very conservative. But there were still semi-underground publishers; they didn’t like me either. I was just flummoxed and I was discouraged. It sounds really overdramatic, but there were many times in the ensuing twenty years where I was thinking about killing myself. All I wanted to do was be a cartoonist and nobody would even think about publishing my work. It was just not going to happen.

Of course, I had to do something with my time, and for money. I had a patchwork existence for a few years, then in 2005 I moved back to Canada. Then I almost immediately was diagnosed with leukemia, which delayed any plans I had. After I failed to die, and was fated to keep on living, I went for a few college courses and learned how to be a “support worker” for people with mental and physical disabilities. I had become interested in such people, for some unknown reason. I must say, I really enjoyed that work, and was very honored to be a part of the disability community. I did it for nine years, but had to retire in 2016 because of my poor health.

But in 2013 I had started to get recognition as a cartoonist again, here in Canada. I was notified in 2013 that this Toronto organization I’d never heard of – the Joe Shuster Awards, because Joe Shuster was Canadian – wanted to give me a Hall of Fame award, basically a lifetime achievement award. At first I was ignoring their emails, not reading them. I didn’t know who they were or what they wanted and I thought somebody will just rub my nose in my failure. I didn’t want to even talk about comics. I had tried to eject comics from my life. Which was kind of like cutting my head off. [laughs] Finally, somebody told me, answer those emails — they’re trying to give you an award! By the time I did that it was almost time for the awards ceremony, so I didn’t have to time to go to Toronto for it. I recorded a video and sent it to them to say thank you. I hardly knew what to say. I was still very divorced from the comics community. In the video, I seem quite dazed, and possibly brain-injured.

It all made me realize, somebody likes my work. Then a gang of young fans and publishers – well, young to me, I was in my sixties – were in touch with me and interviewed me and offered me the chance to be published again. I was absolutely astonished.

What came out of that was contact with Andy Brown, the publisher of Conundrum Press in Nova Scotia. He is a very fine gentleman. We talked and he said, let’s put out a collection of your earlier work, and this became the new book. It was put together the way I thought it should be. Respecting the author’s judgement is one of the hallmarks of Canadian publishing. And now Andy is willing to publish any new work I do. He didn’t have to twist my arm.

So I’m having my renaissance and it’s the biggest surprise of my life. I am so grateful that these people wanted to find me and wanted to recognize my work. I honest to god thought that my work had been completely forgotten, was never going to be exhumed, and that nobody was ever going to hear the name of Neil the Horse again, or Arn Saba, or Katherine Collins. I had written it off. I thought, okay, my life’s over. I was just trying to hang on until I could die, basically. I had almost no reason to be alive. This completely changed my life.

Unfortunately while all this was going on I also was very ill. Earlier this year, I almost died in the hospital, from diabetes. Earlier, I almost died in 2006 from leukemia. And ever since then my health has never been good. In the past month I’m feeling a lot healthier and stronger and it seems more likely that I can go ahead and have a little more of a career. The whole thing has been a surprise. Getting sick has been a surprise. Getting recognized again has been a surprise. Staying really sick has been a surprise. And I’ve been trying to see if there’s any way I can be strong enough for, as I like to say, one more chapter of my life. The latest surprise is that now, suddenly, I’m stronger and I have more energy. But I can still barely walk. I’ve lost my mobility. I don’t know if that’s going to be repairable or not, but luckily I don’t draw with my feet. [laughs]

I’m sure that being an artist your first thought about this wasn’t about your transitioning; your first thought was, this must be because of my art.

It’s pretty obvious, really, looking at it now. [laughs] I don’t know why I didn’t expect it. I certainly got a lot of bad reactions from individual people in my life. I lost many of my friends and I lost several members of my family. I mean maybe I can put some of my obliviousness down to living in San Francisco at the time, where you can do anything. As many artists do, I have a tendency to doubt myself and doubt my work, so if people rejected my work, I didn’t think it was because of being transsexual. I thought it was because they caught me and figured out that I’m no good. [laughs]

Impostor syndrome.

Exactly. I was accustomed to getting a lot of scorn and rejection from the superhero contingent of comics. All the time that I was going to conventions, through the '80s, I would be brushed off by superhero fans and superhero artists. There was one professional who for some reason took exception to me and to Neil the Horse. He would come around to the table where I was sitting and make rude remarks and act angry. I was on a panel with him once and he seemed very defensive – not just towards me but towards the whole new crop of people during the black and white boom, doing comics that were not superheroes. He was trying to argue that superhero comics were just as literary and serious as anything. “I’m writing comics about real people, they just happen to be superheroes.” I remember him saying that.

I wasn’t the only one who got that kind of reaction. And I was accustomed to that. Back in the early '90s the comics business was still run by straight white men, and I’d lived all my life with horrible treatment from straight white men who could tell that there was something wrong with me. I wasn’t gay. I’ve never been attracted to men, I’ve always been attracted to women, which is one of the reasons I was so slow to realize that I was transsexual. But I was accustomed to men being scornful and rude and nasty, so I chalked it up to that. My work was not hyper-male and violent and they were able to get rid of me, finally. That’s what I thought. I thought also that if I had been any good, someone would have remembered it. But all through the '90s and the first decade of the 2000s, never a mention, never a peep – nothing.

So I had to find another life. I became a social worker and I’m very glad I did that. I feel very grateful. It became a really important part of my life. That’s probably what saved my life. I was doing that and people depended on me. But I’d come home and feel very alone. My partner Bobbie Bentley died in 1999 and I’ve never found another partner. For eighteen years now. Lesbians of my age were taught in the 1970s that transsexuals were evil and to be scorned. I’m very lonely and unhappy about that, but that’s the way it is. If it hadn’t been for my work with the disability community I really would have had no reason to live at all. That’s something I still think about. I wanted to die for a long time, because I didn’t enjoy being alive. Now I’m happy to be alive again.

Are you drawing again?

I haven’t drawn a single picture of anything, for any purpose, at all, since 1996. I bought a Wacom Cintiq, which is a large touchscreen you can draw on. I used it for repairing old artwork that had been damaged to put the anthology book together. Now I’m going to start to produce more comics. I’m going to start drawing again. But to this date right now, I still haven’t drawn for 21 years.

You mentioned that you were working on a graphic novel years ago. Are you planning to go back to it?

That’s the idea. Never throw away good work. It was all pencilled and I started to ink it and I stopped in the middle of the inking. Of course I kept it. I lost it for about eight years, but I found it again. [laughs] My idea is to scan the pencilled pages and then ink them on the computer, on the Cintiq, but I’m going to add some more pages. Over the almost twenty-five years it’s been sitting in a box, I’ve been thinking about it. I’ve decided that there are certain parts of the story where I rushed the action because I was trying to keep it to 64 pages. That’s no longer necessary. I can flesh out some sequences where instead of being half a page they can be two pages. I’m going to start by inking the pages that are fine the way they are. I don’t think it’s going to be too difficult to get going on drawing again, and I’m looking forward to it very much.

So more Neil the Horse?

Yes, it’s a Neil story. I never have yet come up with a good title for it. It’s based on a real building in Toronto, an old theater that had been used for many different purposes. Its last use was as a vaudeville theater back in the twenties and then it was just locked up and left sitting there. I managed to talk my way in and there were still things sitting around that had been there since the 1920s. People just walked out one day and the doors were locked. There were things written on blackboards and notices for artists and makeup sitting on the tables, and old-fashioned lightbulbs. It was an absolute time capsule. I went in and took hundreds of photographs and thought this would be a wonderful setting. It turned out not long after that, somebody in Toronto bought the theater and decided to restore it. That’s what my characters do in the story – they get ahold of this theater, restore it, and put on a show. There’s lots of twists and turns in the story, of course, but I like to describe the story as a love story or homage to the history of live theater and the performers who for thousands of years have been performing on stage.

Well I can’t wait to read it and I can’t wait to hear the musical.

I’m going to put that online. I’ll probably just give it away. I own the copyright to the material, but the recording is owned by the CBC, so legally I can’t sell it. I want it to be out there. And once I finish the theatre story I’m planning to record a whole bunch of new songs. I’m going to somehow get the money together to do my own recording session so the songs for that story will be made available. And I have a further bunch of other songs – probably thirty or forty – that have never been recorded. It’s one of my many projects.

I’ve got hundreds of story ideas for new Neil the Horse adventures. Who knows what I’ll do? It’s a different time now and I’m a different person, to some extent. I don’t need to tell you, the world is in a very serious mood. Everybody is angry and everybody is scared and there’s lots of terrible things going on everywhere. I think it would be hard for me to put out stories where everything is just nice and happy. My stories never really tackled anything deeply serious. I don’t usually have villains but the villain in the radio play was a South American dictator. I was making fun of the figure of strongman dictators. That was a bit serious. I’m trying to find a way to still have my stories be recognizable Neil the Horse stories – to promulgate happiness and make the world safe for musical comedy – but also acknowledging some of the more difficult things that are going on. That’s going to be a challenge, but I’m going to see what I can do.

It can be nice to have a pleasant humanistic story and forget about the world briefly.

That’s true. My imagination and my sense of humor tend in that direction. If I’m just sitting down looking out the window, I still envision fairies and talking animals and people singing and dancing – or animals singing and dancing. It’s what my imagination and sense of humor are about. I think I’ll find a way to put that out there and maybe put it out as a partial antidote to the horrible things that go on. We’ll see what happens. I never like to plan too much in advance what I’m going to do. The theater story is different because I want to finish it, but other than that I’m deliberately not making a list and checking it twice, for which of my hundreds of possible stories I will actually do. I’m waiting to see what I feel like doing at that time. I’ve always liked improvising. Whatever I do, I improvise.

One other thing! When we were talking before about how early in my life I got into comics, and I don’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t into comics, I always want to emphasize that my mother was a cartoonist and a comics collector. I was marinated in comics through her influence. Her grandmother – my great-grandmother – was also a cartoonist. When I transitioned, the reason I changed my surname was because of my great-grandmother. Dolly Collins was her name, and I wanted to draw a line connecting me and her, and through my mother. Dolly had a daughter, Hilda Collins, who was not an artist of any kind, and Hilda’s daughter Allison McBain was my mother. My mother inherited Dolly’s artistic proclivities and then so did I. I wanted to trace this line between me and my mother and Dolly, as a matrilineal line of cartoonists. My niece – my brother’s daughter, Rosa Saba – is also a cartoonist. [laughs] So I didn’t have a choice. It was obviously going to happen. [laughs]

What kind of work did Dolly do?

I’ve only seen a little bit of it. I have a box of her cartoons and I have several of her oil paintings on the wall, but she did children’s stories, basically. The drawings that I have are funny animals, from the days before that term would have been used. Animals you might see in a late 19th-century illustrated children’s book and they’re singing and dancing around. Sometimes I think that I’m Dolly Collins reincarnated. [laughs] Wouldn’t that be cool?