On May 5th, 2016, the world has lost Siné, a great illustrator, cartoonist, and political satirist who opened the way for a generation of French cartoonists, humorists, and writers. From Charlie Hebdo to Siné Mensuel, the story of Siné spans over six decades of French art and politics, and yet he is not very well-known abroad. He was a great artist, revered by his colleagues, but it is his involvement with politics that split his audience between his few but devoted fans and his numerous opponents. This is a tribute to a genius... and a friend.

At 14, Maurice Sinet joins l'Ecole Estienne to learn formal drawing. This will turn out useful when, during the Algerian independence war, he will have to forge fake passports for Algerian fugitives. But it is his discovery of Saul Steinberg that makes him want to try creative drawing and profoundly affects his style. He becomes Siné. In the mid-1950s, his first book of cynical wordless cartoons is awarded a prize; the second one targets his favorite prey, the Vatican, and the third one is a little apolitical playing-around with French words containing the syllable “chat” (cat), and illustrating them with cats. Unexpectedly, this little book will be a huge success, translated in other languages when possible, making him rich and popular for the first and almost only time in his career.

With this fame in hand, he is able to start a career as a political cartoonist in the general press. Siné is a self-made political activist, whose very strong opinions are forged out of rage, integrity, instinct, and also a natural-born allergy to every kind of authority, whether it comes from the police, the army, the boss, the church or the State. His first spontaneous political involvement is in favor of the Algerian independence, and against his own French government. His style is a change from “funny little cartoons.” He is aggressive and violent; condemns, mocks and ridicules president De Gaulle, the army and France's colonialism, while supporting the armed resistance of the Algerian people. His pride is to be hated by a growing number of L'Express readers.

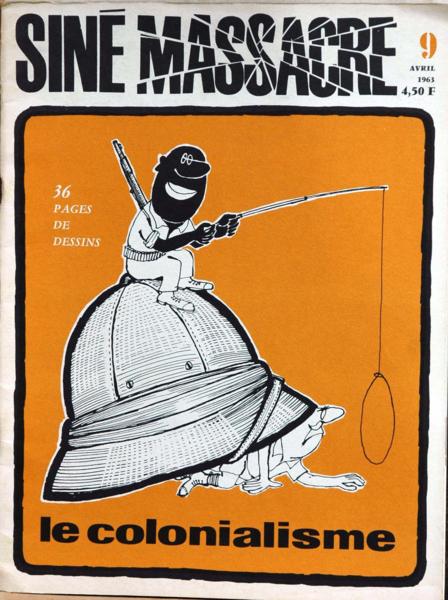

When one of his cartoons is refused, he quits L'Express and founds his own journal, Siné Massacre, in 1962, in order to be able to publish anything he wants. Cartooning is redefined as an anarchist weapon, used to criticize, satirize, and provoke. He slams conservatism and racism, capitalism and religion, nationalism and colonialism, French censorship and violence, US imperialism and Israeli Zionism, at a time when all those values are mostly sacred. Each of the nine issues of Siné Massacre ends up in a trial, heavy fines, and censorship. The journal sinks, but Siné has found his heroes, the revolutionaries of the third world. He will travel around the world to meet them: Malcolm X, Ahmed Ben Bella, Fidel Castro, but he will criticize them when he decides they betray the Revolution. He befriends them, as well as other French intellectuals and provocateurs such as Jacques Prévert, Boris Vian, or Jean Genêt, and seduces them with his irresistible sense of humor.

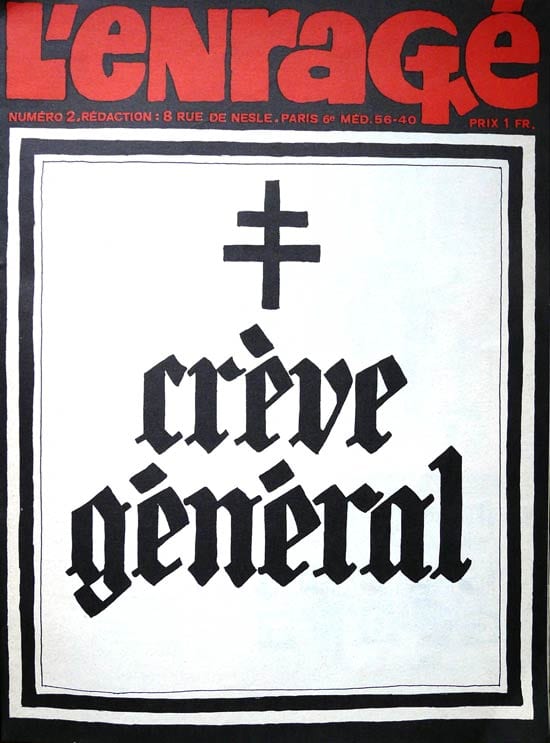

May 1968 in the streets of Paris, Siné smells the scent of the revolution he was expecting, during the student uprisings. Against police brutality, but also because traditional newspapers, parties and trade unions are too shallow for his enthusiasm, he decides to create a new journal, L'Enragé, to support the revolution. L'Enragé becomes a university for cartoonists later to become famous in Charlie Hebdo (Cabu, Gébé, Reiser, Wolinski, Willem) but, then again, he is too radical for his time and the journal folds after only twelve issues. Original editions of Siné Massacre or L'Enragé are available on eBay, but the publisher who would make a book out of them today would deserve a Pulitzer Prize, or an honor medal for courage! Although he briefly collaborates with them in the 1970s, Siné refuses to join his friends in the satirical newspapers Charlie Hebdo or Hara-Kiri, which he finds funny but ugly, and not political enough.

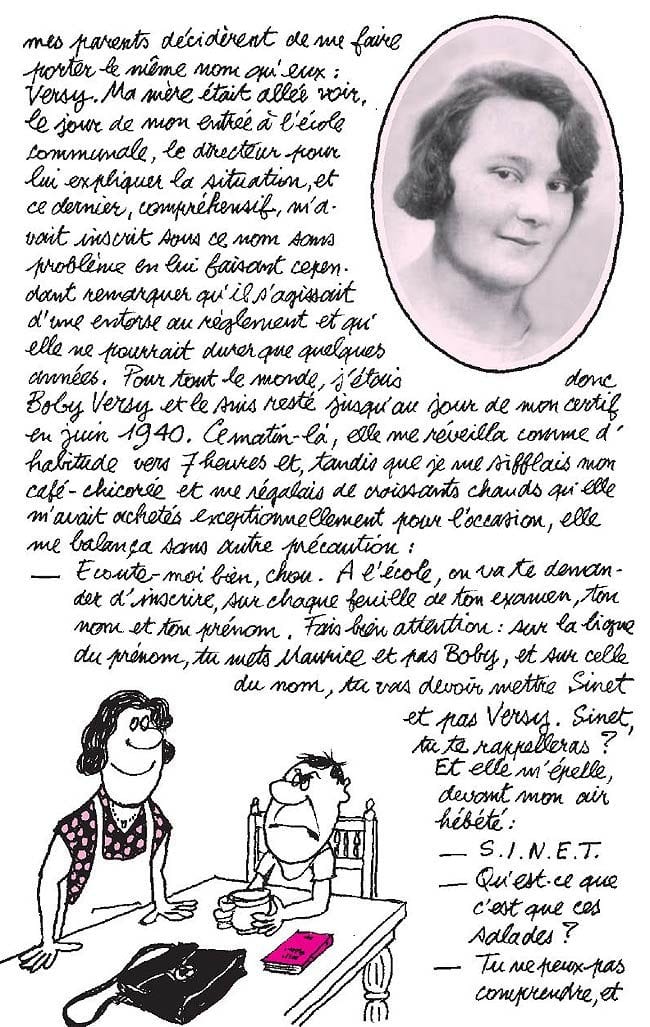

Censored in the general press, Siné luckily has other passions and talents. His rage, when it comes to politics, is as large as his heart when it comes to love, friendship, cats, parties, wine... and music. Music of the oppressed, of course, as Siné is a fan, an expert and a collector of jazz (traditional and free), gospel, soul, salsa, flamenco etc. He gets to draw in other media, including book and record covers, festival posters and music columns in jazz magazines. After having started with wordless cartoons, he develops a new style that he will use for the rest of his life, what he calls his “zones”: a text on one or two columns of a journal, handwritten (with his unmistakable hand-writing), and intertwined with cartoons. He shows a talent for writing as well, using a very rich and slang-tinged vocabulary, creative expressions, and hilarious metaphors. In music as in everything else, Siné is not the kind to like or dislike: he loves and hates, with passion, and he writes it as he feels, making friends or foes for eternity.

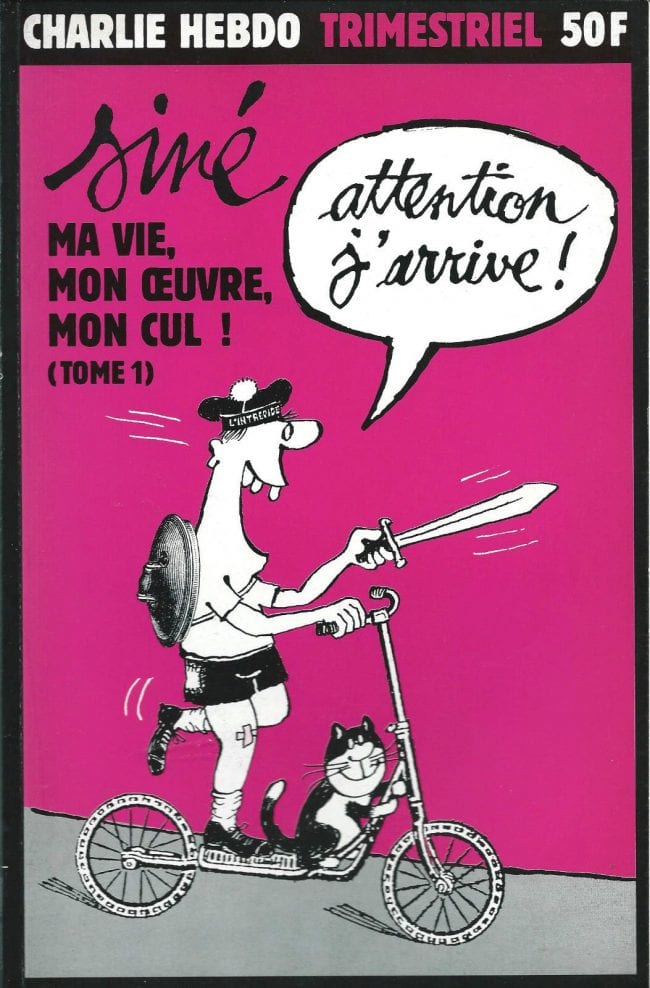

In 1992, the new Charlie Hebdo is created by Philippe Val, who hires Siné along members of the first edition and young cartoonists such as Charb or Tignous. This version of the journal will be political, as Siné wished, and Siné will get his “zone” where he can write and draw whatever he wants. For 15 years, he will continue expressing his radical opinions, progressively alienating himself from Val, consistently opposing imperialist wars, capitalist projects, and supporting the Palestinian struggle. The unexpected success of Charlie Hebdo guarantees Siné a safe job, but also a growing number of fans. In his zone and his autobiography (aptly titled My Life, My Work, My Ass), much like Crumb, he draws himself and expresses his opinions wholeheartedly, with no secrets or taboos, without trying to look like a hero. From his political enemies to his musical heroes, from his sexual failures to his health issues, he confides to the reader, who becomes a friend. He jinxes his fear of death by publicly deciding to be buried with his friends under a giant sculpture that he designs, that gives the middle finger to the grim reaper.

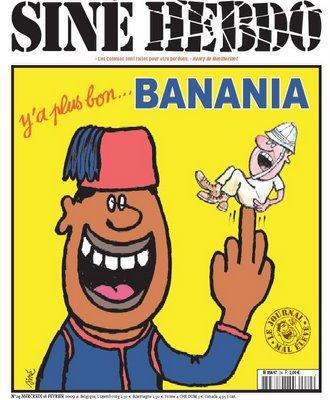

Using the infamous accusation of antisemitism that a French court of justice will later dismiss, Philippe Val manages to fire Siné from Charlie Hebdo in 2008. Supporters of Siné include famous humorists that recognize their debt towards him (Christophe Alévêque, Guy Bedos, Benoît Delépine, Philippe Geluck). In a world without Siné, it would not be possible to draw and mock the powerful, the sacred and the taboo. A world without Siné is a world where freedom of expression is really at stake. In the name of this legacy, in 2008, his supporters help him found, at 80 years old, yet another new journal. Siné Hebdo is a weekly paper that lasts for 20 months, and is followed by the monthly Siné Mensuel, whose May 2016 issue was published the day before his passing. Explicitly political (every issue will include a column on Palestine), the journal will also include columns on culture and counterculture. Old friends are called out, but new cartoonists or columnists are hired (I will be honored to write about music). Each collaborator is free to write or draw whatever he or she pleases but, unlike Siné's previous attempts, this journal is professionally managed by his wife, Catherine. Siné wants a beautiful journal and he is obsessed with every graphic detail. He is responsible for the cover, in addition to his expected “zone,” where he remains as radical as a teenager.

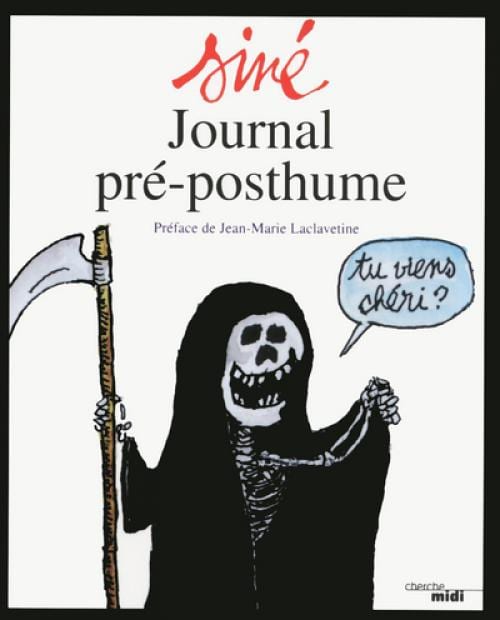

In 2013, Siné's health is failing and a leukemia sends him to the hospital for what he thinks is his last trip. Having recently learned to use a computer, and his mind being totally alert, he decides to write his memoirs, to describe his physical and mental feelings from his “death bed”, and to publish them almost daily on the journal's website. Incredibly moving, witty, funny, beautiful, and sprinkled with rage and love, these texts and drawings will have such a success that they will be published under the name Pre-posthumous Journal. Sick as he may be, he nevertheless keeps putting his energy in signing, and convincing his colleagues to sign, petitions that he sees as useful -- against the collaboration of the Angoulême comics festival with an Israeli sponsor, in favor of the Syrian refugees in Calais, against the state of emergency in France etc.

His last “zone,” the day before he passed, alludes again to his fear of dying: “It's horribly boring to think obsessively about the approaching death, the funerals and the family grief! I also think of all the motherfuckers who will be rubbing their hands, and it annoys the shit out of me to die before them!” After informing the reader that he will undergo a surgical operation, he admits: “My heart is in my boots, and I confess that I squeeze my buttocks like an olive press, to relieve the stress!” On May the 11th, he was cremated under the music of Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Charles, Otis Redding, Dottie Peoples and others. His urn has been placed inside his tomb, under the big finger, awaiting for his friends to continue the party...