Back in December, the family and I visited some friends down South and, on the drive from the airport, my buddy asked if I wanted to “check out his childhood comic shop." Obviously, there's only one answer to that question.

So that's how I ended up at the Book Nook, an eclectic used bookstore/comic shop in Atlanta, Georgia. Unlike my past columns, this time we had four kids with us, so flipping through issues for three hours was out of the question. Instead I went for a power browse, rifling through boxes as fast as I could and pulling out anything that looked even remotely interesting. After a half hour or so, I had a two-foot pile (not exaggerating) and had to make some snap decisions before meltdowns ensued. I went a little over my $20 goal ($32 to be exact), but I walked out with a stack of books and supported a long-standing local bookstore, so win win!

Here’s what I found:

Trident #1-8 (August 1989 – September 1990)

My tastes in comics are all over the map, but I have a special love for ‘80s and ‘90s British anthologies. There was such intense passion for the medium back then, and it went so much deeper than just 2000 A.D. and Warrior, or Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison. There were hundreds of talented creators publishing comics in series like Crisis,[1] Revolver, Escape, Deadline, A1, and Electric Soup.[2]

Trident Comics, an offshoot of Neptune Distribution, a comics distributor based in Leicester, was a small press publisher in the late '80s, and this short-lived anthology was its flagship title. The series was edited by Martin Skidmore, who had previously edited the Fantasy Advertiser, a British adzine. If you think of these anthologies as a poker hand, Trident had a pair of aces: Bacchus by Eddie Campbell and St. Swithin’s Day by Grant Morrison and Paul Grist. But the series attracted a surprisingly large number of other well-known creators to its eight issues,[3] including Neil Gaiman, Phil Elliott, John Ridgeway, Alan Davis, and Mark Millar.[4]

Bacchus

Bacchus, Eddie Campbell’s long-running series featuring the Greek god of wine, has a convoluted publishing history, but the eight tales printed in Trident are some of the earliest episodes.[5] According to Campbell, when it started, “Bacchus was supposed to be a superhero comic, but it became much more philosophical. Its original title was Deadface,[6] but the paradox is that Bacchus… is this huge, life-affirming symbol.”[7]

With his black trench coat and sailor’s cap, Bacchus resembles an elderly Corto Maltese. His weathered face has the texture of petrified tree bark, and his sunken eyes are surrounded by fissures of spidery crow’s feet. In many of these stories, he is traveling with an unidentified group of people, spinning fireside tales into surrealist nightmares. He’s like an intoxicated history professor, spewing didactic monologues on subjects like the origin of fashion. The first story, “Look Ma, no deoxyribonucleic acid!,” is a rambling story about the philosophical incompatibility of science and mythology in explaining the origins of life.

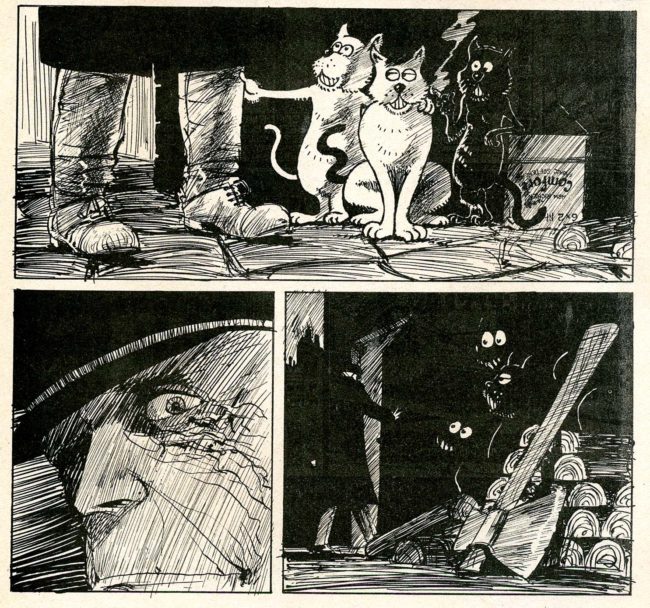

One of my favorite tales is “Legless!” from the third issue. It’s a jam comic based on an idea by Stephen Bissette that was “scribbled on the backs of 9 business cards at Albany N.Y. rail station and executed in England with the help of Phil Elliott, Ed Hillyer, Trevs Phoenix, Alan Moore, and a visiting Jose Muñoz.” What a lineup![8] (check out the cameo by Moore’s Maxwell the Magic Cat). Compared to the other denser stories, this one is sparse. Ostensibly a drunken nightmare about Procrustes “the stretcher,” it’s filled with hallucinations of amputated limbs and flying animals.

Campbell's ambition and enthusiasm for the medium are evident in his kitchen sink approach. His art mixes all kinds of tools and techniques, including chaotic brushstrokes, scratchy pen lines, Kirby-esque photo experiments (see above), and various textures, hatching, and tonal patterns. He’s also a master at controlling mood with light and shadow, and his hand-lettering is highly expressive. Obviously, Campbell’s mastery is well-known around these quarters, but this was the first time I branched out beyond From Hell and some random Alec stories. Clearly, I’ve got a lot of catching up to do!

"St. Swithin's Day"

Along with Bacchus, the best story in the series was this four-part tale about a disturbed teenager plotting to assassinate Britain’s Prime Minister,[9] written by a 28-year-old Grant Morrison.[10]

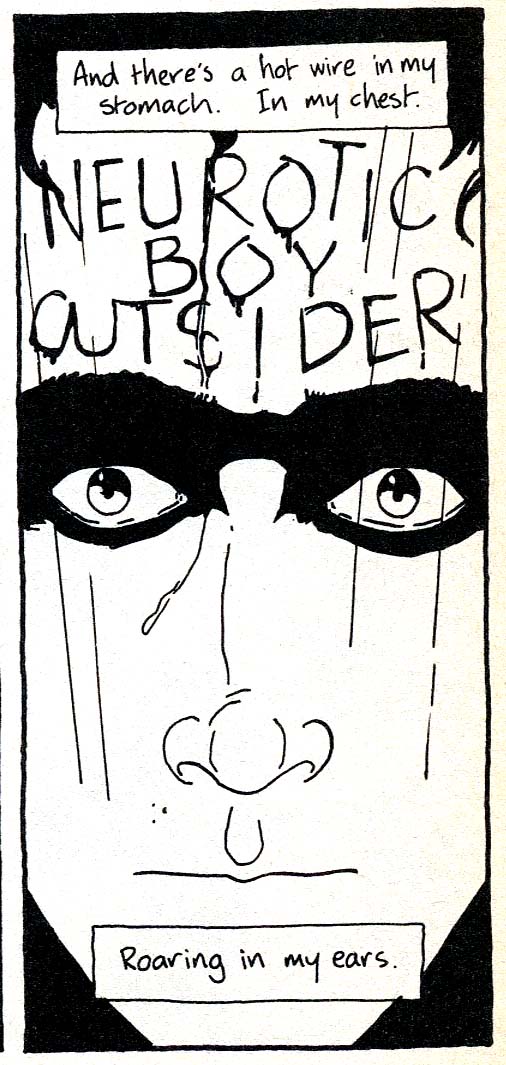

“St. Swithin’s Day” is one of Morrison’s best short stories, up there with "A Glass of Water."[11] Its nameless protagonist, who identifies himself only as "neurotic boy outsider," is, of course, semi-autobiographical (the story is supposedly culled from Morrison’s diaries), but he’s also J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, wandering the streets of London instead of the avenues of Manhattan, but still spouting the same pop misanthropy, and the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious, hellbent on bringing anarchy to the UK.

But who was St. Swithin anyway, and why did he get his own day?

St. Swithin’s Day is essentially England’s version of America’s Groundhog’s Day. Swithin was the Bishop of Winchester in the 9th Century. As the legend goes, he was a humble man who asked that, when he died, he be buried outside in the graveyard rather than inside the church’s crypt; however, when his body was exhumed and moved inside the cathedral a century later, a great storm settled over Winchester, representing his despair at the desecration of his grave and contravention of his final wishes. Over generations this anecdote was immortalized in a nursery rhyme:

St. Swithin’s Day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain

St. Swithin’s Day if thou be fair

For forty days ‘twill rain nae mair[12]

Thus, as the folktale goes, it is believed that on July 15, if it rains it will continue to rain for 40 days.[13] Morrison uses rain throughout the story as a symbol for the young man’s anguish. “Everything bad happens in the rain” was the story’s tagline on its cover when it was re-published, and the pessimistic narrator even visits Swithin’s original grave in Winchester.

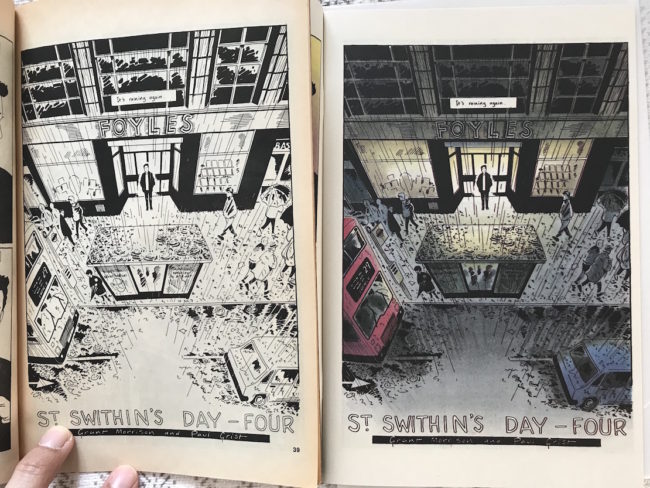

Paul Grist's art is head and shoulders above the other contributors in Trident, save Campbell. A devotee of the ligne claire style, his minimalist compositions are rendered with a graceful economy, and his black-spotting is on par with Xaime or Toth.

In 1990, Trident released a standalone collection of St. Swithin’s Day in color. Grist’s open, uncluttered panels are well-suited to color, and, if I'd never seen the original black-and-white story, I'm sure I'd love Steve Whitaker's muted palette of watercolors.[14] There are definitely some panels where he really nails it, adding beauty and depth to the story (see above), but, for the most part, the colors are unnecessary (although I’m sure they boosted sales in the direct market). The black-and-white version is far superior.

One of the things that really stands out is the story’s pacing. Its tight narrative rhythm shows confidence and understanding of visual storytelling, and the descending countdown structure ratchets up the tension with each chapter. But the true brilliance of the story is its ambiguous ending. After he is tackled by the Prime Minister’s bodyguards, the “neurotic boy outsider” blacks out, then wakes up aboard a train. What happened? How did he get there? According to Carey, “either the whole thing was some mildly amusing diversionary youthful daydream… or else the pleasant train ride is the hallucination, a ‘safe’ memory Nameless’s brain conjured up after the five-0 have knocked his ass unconscious.” Both are valid, but I interpreted the final scene differently. With its tunnel imagery, I assumed that the teen had died in the altercation, and that this train journey was symbolic (i.e., the light at the end of the tunnel). No longer afflicted by existential despair, he is finally at peace. Whatever the case, it’s a masterful ending, both tragic and hopeful.

Dom Zombi

First impression: I wanted to like this strip, but I just couldn’t get into it. Dominic Regan’s[15] artwork felt overly cluttered and impenetrable, and the first chapter about a punk vampire detective fell flat, so I decided to read everything else and come back to it.

I’m so glad I did!

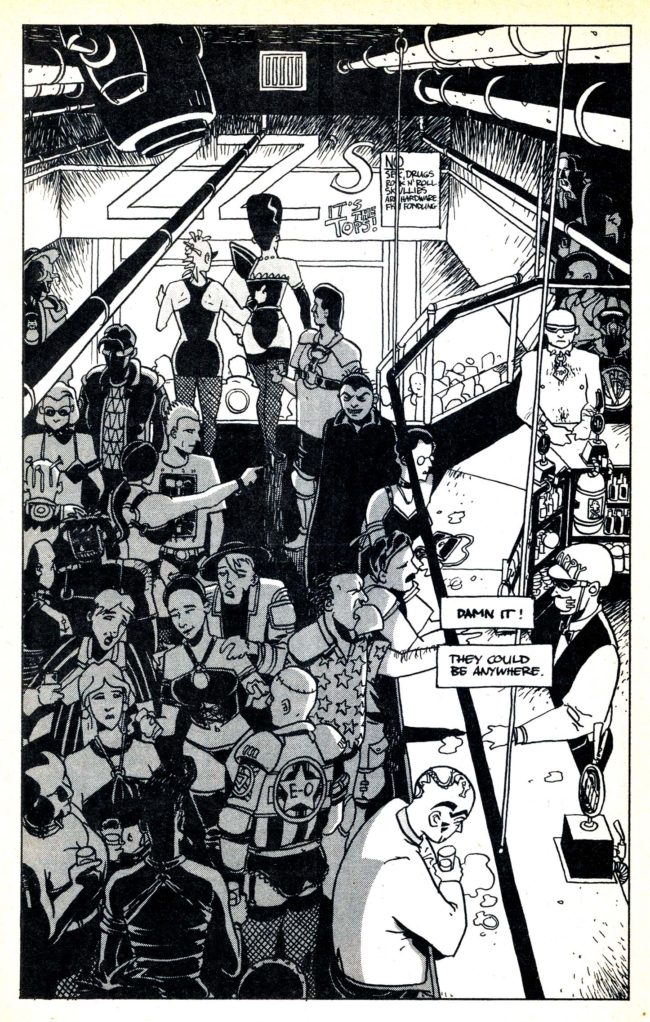

Like “Bacchus,” "Dom Zombi" appeared in every issue of Trident. While the opening episode is a spin on the classic horror genre, with humans preying on vampires, instead of the other way around, by the third issue the strip evolved into something very different. Suddenly, Dom lives in a magic house that drifts outside of space and time, defying the laws of physics. This simple conceit unleashed Regan’s imagination, and the rest of the series is a wild hallucinatory trip where the story is just a rough context for Regan's surrealist experiments.

Regan’s panels are full of jagged angles and harsh geometries, warped perspectives and Ditkoesque mindscapes. His backgrounds are like abstract canvasses saturated with floating shapes, often composed with slivers of zip-a-tone scattered like shards of broken glass. In addition to Ditko, I see flashes of Kirby, Miller, Niño, Kojima, and even, oddly, Panter, but the work still feels totally original. Regan's style is an acquired taste, and there’s not much story per se, but once I came back to it, I began to appreciate its ingenuity.

The Light Brigade

As far as Trident’s newcomers go, my favorite was “The Light Brigade” by Nigel Kitching. The series was co-created by Neil Gaiman, though he set sail for the colonies after the first chapter,[16] so it’s no surprise that it reads like an early Vertigo concept that was never fully developed.

The story focuses on a superhero team, though they're really just glorified computer avatars for a motley crew of digital cyberpunks. The most fascinating part about “The Light Brigade” is how it foreshadows our present Internet-addicted culture. In the story’s world of abstract chiaroscuro technology, society is run by an entertainment mega-corporation and people spend their lives literally hard-wired to their computers while their minds journey through “para space.” Sound familiar?

Kitching’s blocky art makes heavy use of photo collage and various digital effects. It’s a shame he never got the opportunity to work for DC like so many of his peers. While his story is not always easy to follow, the characters and concept had potential, and it was just hitting its stride in the final issue when D'Israeli came onboard.

Shadows

Remember that show Millennium by Chris Carter, the creator of X-Files? "Shadows," scripted by Mike Collins and Robin Laing, is similar in concept, with paranormal CIA agents gone missing and some mysterious psychic cult, but with its confusing plot, generic characters, stilted dialogue, overblown prose, and inconsistent artwork, it never amounted to much.

Five chapters of “Shadows” appeared in Trident, drawn by three different artists (Pete Martin, Kenton Archer, and Vince Danks). Martin and Archer’s characters are decently drawn, with a solid grasp of anatomy, but there is something missing. They feel stiff, like mannequins. The story disappeared for a few issues then returned for one last gasp, this time penciled by Danks and inked by Steve Pini. The art is a major step up from the earlier chapters, but by this point, it was too little, too late.

"Lowlife"

First impression: This scene pretty much sums up "Lowlife."

The story is so clunky, I thought it was a poorly translated manga at first. It's certainly mimicking manga with its Japanese characters and Godzilla monster. It's even set in "Neo Kabuki."

Steven Martin, another newcomer, definitely had drawing chops, though his panels are over-rendered, and flooded with superfluous details. Then again, the awkward dialogue and confusing story didn't give him much to work with. It doesn’t seem like he did any other comics work after this, which is a shame.

In addition to all the recurring features, there were several great standalone pieces in Trident. One of my favorites is "The Shipwright” by Stephen Walsh and Kellie Strøm, a dreamlike story with mythical beasts and flying boats. Strøm’s black-and-white pages are filled with decorative Art Nouveau flourishes reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley.[17]

Another standout is “Four Days One Summer” by Phil Elliott, a slice-of-life vignette which reads like a lost Tale from Gimbley. It's about teenage romance and summer holidays with a personal touch that feels semi-autobiographical. It’s got that same wistful tone as some of Eddie Campbell‘s Alec strips.

In the final issue, Grist returned to illustrate the first and only chapter of "Falling Angel," a twisted story by Andrew Hope about an angel who abandons her post in Heaven to inhabit an aborted fetus. Oh, how I wish this bizarre premise had been… err… fleshed out more.

Trident ended after its eighth issue and I have read some comments online that this was due to slipping sales and late shipping of its titles. While I have no doubt this is true, I also wonder if it wasn’t also driven out of business by competition from Atomeka Press, a London-based publisher which launched its own anthology, A1, in 1989. A1, edited by Dave Elliott and Garry Leach, was simply a superior book. It boasted a far more impressive line-up of both British and American talent (including Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, Bill Sienkiewicz, Brian Bolland, Barry Windsor-Smith, Dave McKean, among many others) and had much better production values (each issue was published in the “prestige format” with brighter paper and more pages).[18] Many of Trident’s contributors apparently moved to A1. For example, new episodes of Bacchus appeared in several issues, and Gaiman, Morrison, Elliott, and Regan also contributed to the series.

Still, whatever the reasons for its demise, Trident had its moment in the Sun and these eight issues contain many gems. If you get the chance, check them out.

Not bad for $2 per issue, right? And that was only half of my haul!

NEXT: The Book Nook – Part 2!

BONUS FEATURES:

Incredible Hulk: Last Call (June 2019)

Right before our vacation, I gave my son a copy of Spider-Man’s Greatest Team-Ups, which includes reprints of stories by Lee, Ditko, Romita, as well as a couple Frank Miller issues. It’s a solid, if somewhat random collection, but as I watched him devour it, I felt an unexpected sense of envy. What a thrill to discover those classic stories for the first time, even out of their original context. It has been many years since I read comics with such pure, uncritical eyes.

So, if it seems like I’m overly nostalgic in this column, especially for guys like Byrne, Miller, McFarlane, and Pérez, that’s why. Besides, apparently I’m not alone since, in addition to the onslaught of repackaged material, Marvel is publishing new books engineered to stoke those old flames. Case in point: Incredible Hulk: Last Call, which once again reunites longtime Hulk writer, Peter David, with one of his greatest collaborators, Dale Keown.[19]

It's been decades since I read David’s original run, but I was faithful to the end, picking up every issue from the early McFarlane run through Purves, Keown, Frank, etc. I have fond memories of Joe Fixit, the Pantheon, and Rick Jones's bachelor party. But nostalgia just for nostalgia’s sake feels empty, like when a band covers itself. It cheapens the original. Sure, it’s fun to see Keown back on the Hulk, and he hasn't lost a step. His art looks as dynamic and polished as ever, but this anachronistic one-off issue feels out of place, especially compared to the enjoyable, if somewhat overrated Immortal Hulk by Al Ewing and Joe Bennett.

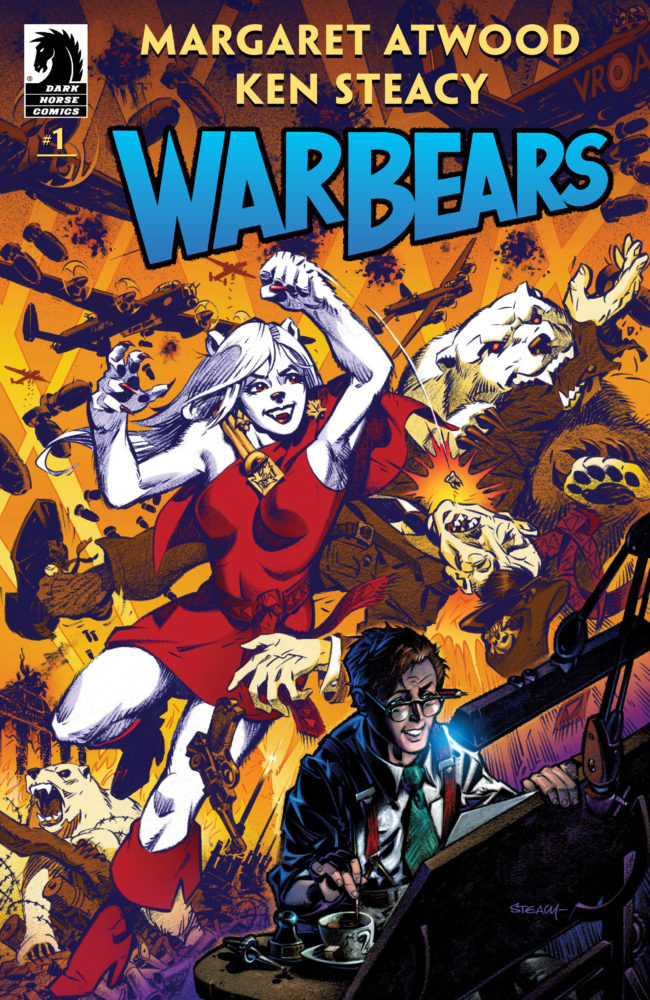

War Bears #1-3 (2018 - 2019)

Speaking of nostalgia, I’m a long-time Ken Steacy fan going back to his ‘80s work on Marvel Fanfare and Astro Boy. Having also just read Margaret Atwood’s dystopian classic, The Handmaid’s Tale, last year, I decided to check out the first issue of War Bears. This comic is far better than I expected.

Despite the misleading covers, War Bears is about anthropomorphic bears the same way that The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay was about the Escapist. The focus is on the cartoonists behind the characters rather than the fictional characters themselves.

Steacy delivers the same strong sense of design and composition, but here he eschews the airbrushed neon coloring for a more subtle hand-painted style which contrasts beautifully with his black-and-white faux Golden Age serials. I was sorry this ended so quickly; I would have enjoyed spending more time with these characters.

[1] It took years, but I finally collected the entire 63-issue run of Crisis. Someday I’m going to write about this series, especially the latter third which contains loads of great stuff that’s never been reprinted. Here’s an example.

[2] Electric Soup is at the top of my want list. It’s mostly known as the series where Frank Quitely got his start, but I also love Dave Alexander’s criminally under-appreciated “MacBam Brothers” strips, the Scottish version of Shelton's Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. It’s hard to find these nowadays, especially the first three issues, and the ones that do show up for sale tend to be very expensive, but I’ve got about half so far.

[3] There were technically 10 issues of Trident if you count the two Trident Sampler preview issues.

[4] Trident published The Saviour, Mark Millar’s first professional work, in 1990. The story, a heavy-handed Messianic metaphor which uses superheroes as Biblical stand-ins, was illustrated by Daniel Vallely and Nigel Kitching. Had the entire six-issue series been drawn by Vallely, I suspect it would be much more highly regarded, but he was replaced by Kitching after the first issue. Although I enjoyed Kitching’s jaunty style on “The Light Brigade,” he was a poor substitute for Vallely, whose stark photo-realistic work was much better suited for the tone of the story. Vallely is an artist I’ve always been fascinated with. He did very little comics work, but his McKean-esque collage work on Grant Morrison’s “Bible John” in Crisis is fantastic. Unfortunately, he left comics to pursue a career in music and photo journalism.

[5] These Bacchus stories came out at virtually the same time as From Hell, which debuted in Taboo #2, also in 1989.

[6] Deadface was published in 1987 by Harrier Comics.

[7] Wiater and Bissette, Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with the Creators of the New Comics, 1993.

[8] Campbell collaborated with many other artists on these early Bacchus stories. For example, in “The 1,001 Nights of Bacchus” in the sixth issue, New Zealand cartoonist, Dylan Horrocks, illustrated five pages.

[9] While some of the specific references are dated, the story’s political disillusionment and alienation still resonates, even moreso today. The story’s seditious subject matter stirred up some controversy back when it was first published. After a profile in the conservative British tabloid, The Sun, under the headline “DEATH TO MAGGIE BOOK SPARKS TORY UPROAR,” the story was seen by some as a threat and it was even condemned by an MP in the House of Commons.

[10] By 1989, when “St. Swithin’s Day” was published, Morrison was already a bonafide star on both sides of the pond. His acclaimed run on Animal Man had already begun (in 1988), and his reboot of Doom Patrol (starting in #19, February 1989) and Batman: Arkham Asylum (November 1989) would cement his reputation as a wildly imaginative writer with a surrealistic vision and penchant toward meta-narratives.

[11] Talk about a dollar bin gem! “A Glass of Water” is Morrison’s short story with Dave McKean in the first issue of Fast Forward (subtitled “Phobias”), which was published by DC’s Piranha Press in December 1992. All three issues of this short-lived anthology are worth tracking down.

[12] It’s impossible not to compare Morrison’s use of this children’s verse with Alan Moore’s similar usage of the Guy Fawkes Day rhyme in V For Vendetta (“Remember, remember, the 5th of November…”)

[13] The St. Swithin’s Day folktale also bears obvious roots in the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark and the great flood.

[14] The story was reprinted by Oni Press in 1998, but surprisingly it's never been resurrected since. If only someone would publish a collection of Morrison’s forgotten short stories. ????

[15] Regan started out assisting Ian Gibson on some “Sam Slade, Robo-Hunter” stories in 2000 A.D., including “The Beast of Blackheart Manor” which was reviewed in the 2nd issue of this very column! The character “Dom Zombi” first appeared in a one-page strip in Aaargh!

[16] Too bad Gaiman didn’t stick around, but I guess things worked out ok for him.

[17] A few years later, in 1992, Walsh and Strøm would reunite on The Acid Bath Case from Kitchen Sink Press, a vastly underrated crime novella.

[18] I highly recommend A1 but I doubt you’ll find it in the dollar bins. I’m still looking for #6.

[19] This is not the first reunion for David and Keown. The pair previously collaborated on Incredible Hulk: The End in 2002.