Bil Keane, whose family inspired the most widely circulated single-panel daily cartoon in the world, died of congestive heart failure on Tuesday, November 8, at his home in Paradise Valley, Arizona. He was 89.

“We’ve just lost the Norman Rockwell of comic strips,” said Mike Peters of Mother Goose and Grimm. “He was as American as Irving Berlin, and that’s why The Family Circus was a part of everyone’s morning. God love you, Bil,” Peters finished, “—’course, I’m sure He has your cartoons already taped on the Gates.” “The Family Circus was Americana on the comic page,” said Mad’s Tom Richmond, president of the National Cartoonists Society.

The comedy in the circle of The Family Circus is gentle and authentic, home-spun and laden with traditional values. “Knee-slapping guffaws were not the stuff of Mr. Keane,” wrote Dennis Hevesi at the New York Times, going on to quote the cartoonist from a 1995 interview: “We are, in the comics, the last frontier of good, wholesome family humor and entertainment,” Keane said. “On radio and television, magazines and the movies, you can’t tell what you’re going to get. When you look at the comic page, you can usually depend on something acceptable by the entire family.”

And The Family Circus was that, in spades, hugs and pulls at the strings of the heart. “It endures as a kind of eternal world of ‘Donna Reed’ and ‘Father Knows Best,’” wrote Matt Schudel at the Washington Post.

“I don’t have to come up with a ha-ha belly laugh every day,” Keane told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2003, “but drawings with warmth and love or ones that put a lump in the throat or tug at the heart. That’s more important to me than a laugh. I would rather have the readers react with a warm smile as they recall doing the same things in their own family. Basically, I set out to entertain. However, if there is a philosophy it is to show that a home where little children have love for one another and their parents for them is the happiest place in the world. It’s a subject that is near and dear to me."”

Keane’s cartoon family grew directly from his own experiences as the father of five and the grandfather of nine. He based his characters on his wife Thel, sons Neal, Glen, Christopher and Jeff, and daughter Gayle. “They provided the inspiration for my cartoons,” he would say, “—I provided the perspiration.”

But the heartfelt endearing aura that floats over the comedy in The Family Circus is only one facet of Keane’s sense of humor. He was an over-the-top public speaker who was the highlight of many cartoonist gatherings, said Arizona Republic editorial cartoonist Steve Benson. Slender and small of stature, Keane often surprised people with a quick wit that veered into biting sarcasm and rampant irony. "He was hilarious," Benson told Scott Craven at the Republic. "He was a great emcee who had an amazing ability to play on words. People were surprised to hear this volcanic stream coming out of a little guy."

In 1980, Keane was on Larry King’s nation-wide radio show, and after King welcomed him to the show, Keane responded in his gravelly voice: “Larry, it’s more than a thrill to be here. It’s a damn inconvenience.”  It was a line, and a comedic attitude, that Keane put on display whenever he was standing at a microphone. Which he did often as emcee of the festivities of the National Cartoonists Society (NCS) at its annual Reubens Banquet. Most non-cartoonists never saw that kind of Keaning, said Michael Cavna in the Washington Post, “but he was laugh-out-loud funny.” Richmond remembers attending his first Reubens weekend at which Keane was moderating (so to speak) the event: “Knowing that The Family Circus was a very sweet and gentle feature, I mentioned I was surprised they didn’t have an emcee with a little more of a sharp-tongued approach. ‘Just wait,’ they said, ‘—you haven’t seen Bil emcee yet.’ I sure hadn’t,” Richmond continued; “I was laughing so hard throughout the awards I barely recall who won what. To say that Bil Keane was only quick-witted is like saying Olympic superstar Usian Bolt is just ‘sort of fast.’”

It was a line, and a comedic attitude, that Keane put on display whenever he was standing at a microphone. Which he did often as emcee of the festivities of the National Cartoonists Society (NCS) at its annual Reubens Banquet. Most non-cartoonists never saw that kind of Keaning, said Michael Cavna in the Washington Post, “but he was laugh-out-loud funny.” Richmond remembers attending his first Reubens weekend at which Keane was moderating (so to speak) the event: “Knowing that The Family Circus was a very sweet and gentle feature, I mentioned I was surprised they didn’t have an emcee with a little more of a sharp-tongued approach. ‘Just wait,’ they said, ‘—you haven’t seen Bil emcee yet.’ I sure hadn’t,” Richmond continued; “I was laughing so hard throughout the awards I barely recall who won what. To say that Bil Keane was only quick-witted is like saying Olympic superstar Usian Bolt is just ‘sort of fast.’”

“He was so funny,” remembered Between Friends’ Sandra Bell-Lundy. “I remember thinking how different his humor style was in person compared to the warm, gentle humor of his comic feature.” Keane might start with the ludicrous comment, “Before I begin.” Followed by an equally inoffensive piece of nonsense: “How many of you in this room have attended one of our dinners before but couldn’t be here tonight?” But he was soon strafing the roomful of tuxes and ball gowns, as Cavna said, “his deft, relatively gentle barbs toward his fellow creators somehow proving as reassuring and comforting as his cartoon.”

The first time the Reubens was held outside of New York, it was in Los Angeles, and Momma’s Mell Lazarus was dinner chairman. (Lazarus said he got the second L in his first name by stealing it from Keane’s first name; Keane agreed.) Keane launched into his after dinner remarks by recognizing the work Lazarus had done:

“Mell Lazarus was dinner chairman. He did fine work chairing the dinner. He had ten chairs at every table.” Another time, attempting to explain the significance of the NCS division awards, Keane deployed another of his patented routines, a strenuous tirade of meaningless double-talk (of which he was a past master), concluding, “I hope I’ve made that clear.” In later years, NCS concluded its Reubens weekend with a roast, and Keane was the first to be so dubiously honored. Lazarus was the second roastee, and Keane took a turn at the microphone: “As a rule, we roast only people we love,” he said, “—but tonight, we make an exception.”

Cathy Guisewite was the first female target at a Reubens Roast, and Keane delivered this encomium: “Of all the women ... cartoonists ... currently making a living ... at the profession,” he said, drawing out his pronouncement by prolonging the pauses between words, “Cathy Guisewite ... is ... one.” Asked once about the future of NCS, Keane said: “I think it lies ahead.”

Jud Hurd, publisher of Cartoonist PROfiles, “interviewed” Keane every once in a while, and transcriptions of their exchange were festooned with word play. “You currently reach close to a hundred million readers daily,” Hurd said, by way of introducing his co-conspirator. “You are an unqualified success.”

“Yes,” said Keane, “and think what I could do if I was qualified.” Hurd remembered Keane had met his wife in Australia in 1942, saying: “Tell us about that meeting.”

“Meeting!?” Keane croaked: “It wasn’t a meeting! It was World War II! It was in all the papers!”

“Let’s skip a few years,” Hurd said, hoping to extricate himself from the verbal dilemma. But Keane wouldn’t let him off so easily: “You can skip if you like, but I’d rather walk normally.”

William Aloysius Keane was born in Philadelphia on October 5, 1922 to Aloysius and Florence Keane, devout Catholics. “I think that being born in October is the reason some people have begun calling me a mysterious name, ‘octo-genarian,’” Keane wrote in the last NCS Membership Album. “I don’t remember much about 1922,” he confessed, “except lying in a bassinet waiting to be syndicated.” Young Bill (two Ls then) “showed an early interest in cartooning,” Hevesi reported, “—as a child, he drew on his bedroom walls.”

Which circumstance, Keane later posited, explained the spelling of his first name: “My parents named me Bill, but when I started drawing cartoons on the wall, they knocked the L out of me.” Not quite. As a teenager growing up in suburban Crescentville in the late 1930s, he and some friends produced a satirical magazine the Saturday Evening Toast, and he started signing his cartoons “Bil Keane” merely to be different. He was joining in: the other artists on the project also altered their names for their signatures.

A staunch Catholic from birth, Keane concluded his education at parochial schools by graduating from Northwest Catholic High, after which, he joined the work force as a messenger at the Philadelphia Bulletin, where, between deliveries, he observed the paper’s staff artists at work (and longed to join them).

During World War II, Keane was a tech sergeant stationed at a desk in Brisbane, Australia, where he observed at the next desk a shapely young woman named Thelma Carne. “I got up enough nerve to ask her out,” Keane later reported, “and we started laughing then and never stopped.” Keane also drew cartoons for Yank magazine and the Pacific Stars and Stripes, for which he created a feature called At Ease with the Japanese. After the War, he and Thel continued a relationship, mostly long distance, until 1948 when Keane returned to Brisbane to marry her.

Back in his home town in the U.S. in 1946, Keane returned to the Philadelphia Bulletin, this time as a staff artist. “I drew staffs,” Keane said. He also edited and drew cartoons for the paper’s 16-page Sunday supplement, Fun Book, for which he concocted the comic strip Silly Philly about a little boy dressed as William Penn, a page of jokes called Mirthquakers, and another strip, Corn Crib, which featured round-headed characters spouting puns. At various times, Keane produced other comic features, mostly short-lived (and none in syndication)—The Master, about a put-upon father; The Suburban Set, about typical family life in the suburbs; and The Silent Set, a pantomime panel. In his spare time, Keane freelanced these and other cartoons to Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, This Week, Look and other general interest magazines of the time. He kept this up for 13 years.

In 1954, Keane contacted the Register & Tribune Syndicate about distributing Corn Crib, but the master minds in Des Moines countered with a suggestion that he do a panel cartoon about an entertainment medium just then completing its saturation of the country, coast to coast. Keane’s Channel Chuckles was the first newspaper cartoon about the medium that newspapers at first feared would render them obsolete; by the mid-1950s, however, newspapers had reconciled themselves to living with their competition and had introduced tv program listings and gossip columns in special television sections, into which Channel Chuckles fit handily. It continued for the next 22 years until 1976.

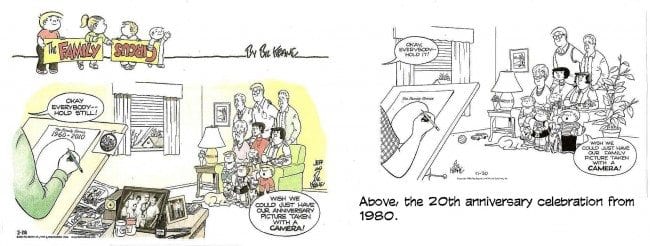

In April 1959, shortly after moving from Pennsylvania to Arizona, Keane approached his syndicate with another cartoon idea. Called Spot News, it was a pantomime gag that highlighted some recently reported event. It debuted in June but began to fade by fall. Unhappily, given the lead time that syndicated cartoons require, 4-5 weeks before publication date, Spot News couldn’t be very topical. But Keane was intrigued by an aspect of the cartoon’s design: the cartoon appeared always in a smallish circle, which newspapers could insert as an “ear” above their front page masthead. Keane liked the circle—a visual novelty that almost guaranteed attracting a reader’s attention no matter where it appeared in a newspaper—and he next produced some family jokes in a circle. Now, he had arrived at a subject he was intimately familiar with.

By 1960, he and Thel had produced five children, four boys and their older sister—a circumstance fraught with gag material for a family-focused cartoon. (In Philadelphia, Bil’s brother Bob lived next door with his nine children. Those Keane boys, gluttons for punishment.) Keane continued to do Spot News while preparing The Family Circus: the syndicate’s plan was to launch Family Circus by switching it for Spot News, slipping it into the syndicate pipeline while hoping client papers would continue the circular cartoon with its new focus. And it worked: “Newspaper editors hardly grumbled about the swapped feature,” wrote Keane’s son Christopher in the first volume of IDW’s complete Family Circus compilation. “They liked the new material and found room for the new comic inside their papers.”

The feature’s title, however, created a small albeit surmountable problem. Keane had christened the cartoon The Circle Family, but his editor at the syndicate thought The Family Circle would be better. And it launched with that title on Leap Year’s Day, February 29, 1960 in 19 newspapers. The inaugural panel shows a front room strewn with toys, and Mom is at the door with a pollster who asks: “Any children?”

Within six months of its launch, the cartoon attracted the attention of the legal department at Family Circle magazine, which threatened to sue. Keane had his editor pondered a host of other title possibilities before Keane opted for The Family Circus, which, he said, “better described his own life experience.” The curtain went up on the new title August 15, 1960. The color Sunday installment first appeared September 10, 1961, and Keane ended Silly Philly and stopped freelancing cartoons to magazines to concentrate on Channel Chuckles and The Family Circus.

In the early years of the cartoon, the paterfamilias has a somewhat different look—a much more bulbous nose being the most conspicuous. “He looked like a big fat clumsy guy,” said Keane’s son Jeff, the present ringmaster of the Circus. In appearance, he evoked the star of The Master, which title,” Christopher Keane explained, “was an ironic take on a father being more of an indentured dupe than master of the house. The gags focused on a constantly bemused, bewildered, and often put-upon dad.”

But the father of The Family Circus was no dupe: he was simply an ordinary dad, and over the ensuing years, he eventually looked more and more like Bil Keane. The nose got smaller, and “Father” started wearing horn-rimmed eye glasses. Keane forthwith eliminated Father’s eyes, explaining: “When you draw glasses and put two dots in the middle of them for eyes, the character looks surprised all the time. I don’t want him to look surprised; I’d rather have him look uncommitted.”

“Mother,” however, didn’t change much (although her hair-do achieved its stylized set after just a year or so). And in deference to her model, Thel, she always had a superb figure. The rest of the family was also modeled on the cartoonist’s. The toddler Jeffy was “an obvious caricature” of Jeff; the little girl Dolly resembled the Keane daughter Gayle. Billy was a “generic little boy” that Keane had been drawing for years who therefore resembled Christopher and Neal and Glen, who went to work at Disney, doing character animation in such films as “the Little Mermaid,” “Aladdin,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Tarzan,” and, most recently, “Tangled,” a computer-animated hit based on Rapunzel. (Keane himself dabbled in animation, overseeing the production of three tv specials starring The Family Circus.) Later, in 1962, Keane added PJ, the enduring toddler, whom Jeffy introduces to a friend by saying: “His name is PJ—but most of the time, he’s called No-No.” On another occasion, Jeffy introduces PJ to another friend: “He has some teeth, but his words haven’t come in yet.”

Running errands and shopping in Paradise Valley, Thel Keane was sometimes recognized as “Mommy” in The Family Circus, and she apparently enjoyed her role as role model, entering into the alter ego fantasy. In the mid-1980s, Keane thought he’d add a new character to his cartoon family by introducing a baby. “My wife was outside the studio working in her garden, the flower bed,” Keane remembered. “I ran out of the studio and said, ‘Thel, what would you think of adding a new baby to the family?’ She said, ‘Well, it’s all right, but let me finish the weeding first.’” No baby was added.

Thel was Keane’s financial and business manager and was a key (“hard nosed”) negotiator (with their lawyer) in getting her husband ownership of the feature’s copyright in 1988. When she died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2008, Keane called her “the inspiration for all of my success.”

“When I first started The Family Circus, it was more exaggerated family humor,” Keane recalled. “Everything would go towards the big laughs. The kind of stuff that Jerry Scott and Rick Kirkman are doing so well now in Baby Blues.” At avclub.com, Sean O’Neal said he liked the early version best. “It was actually funny, even occasionally bordering on risqué as it contrasted the home life of an ordinary '60s dad (and Keane stand-in) contending with his rambunctious kids while also drinking and ogling loose women. Compared to what it would become, in fact, it was downright cynical about the way child rearing can be its own special prison.”

O’Neal goes on to quote Keane who pinpointed the moment “everything changed”—in a mid-1960s panel showed Jeffy coming into the livingroom late at night in pajamas, and Mommy and Daddy are watching television, and Jeffy says, "I don't feel so good, I think I need a hug." As Keane said, "And suddenly I got a lot mail from people about this dear little fella needing a hug, and I realized that there was something more than just getting a belly laugh every day."

“Indeed,” O’Neal continued, “some would argue that Keane never really cared about getting a belly laugh ever again: over multiple decades, through all the shifts in social mores and increasingly sophisticated ideas about comedy, Keane made The Family Circus even more cutesy and sentimental, saying explicitly that he believed it was his responsibility to act as a stalwart for traditional values. Naturally, being so gooey and simplistically, unflappably square—even in a somewhat staid medium like the newspaper comics—made Keane and The Family Circus a frequent target for ridicule.”

O’Neal admitted that Keane was always a good sport about being sometimes the butt of someone else’s joke. But Dilbert’s Scott Adams has another thought: “Critics were sometimes harsh, especially other cartoonists. But allow me to point out the obvious: if other cartoonists could make a family-oriented comic that was as popular as The Family Circus, they would have done it. Bil was a misunderstood creative genius who knew how to write for his target audience. He was also a great guy. I was a big fan.”

Keane knew exactly what he was doing. “I think the injection of the warm, tear-in-the-eye humor is what built a particularly strong following for me,” he said. “Consequently, since I didn’t have to always be funny, I could change the pace of the cartoon. Going from to day from funny, to a warm loving look, to a commentary, and even to inject religion into the feature.” A memorable instance of the latter took place when Dolly asked: “Is God white, black, brown, yellow, or red?” Mommy answered: “Yes.”

“Laughter was a part of the church services I attended as a child,” said Keane, who believed that Jesus must’ve had a sense of humor: “I like to think of him as a guy who got people to listen to him by leaving them laughing and chuckling with one another.” Keane may have trafficked shamelessly in wholesome, but he had a lasting impact on legions of readers, among whom, Lynda Barry, creator of Ernie Pook’s Comeek in altie weekly newspapers, was a vocal representative. Learning of Keane’s death, she wrote:

I was a kid growing up in a troubled household. We didn't have books in the house, but we did have the daily paper, and I remember picking out The Family Circus before I could really read. There was something about looking through a circle at a life that looked pretty good to me. For kids like me, there was a map and a compass that was hidden [in] The Family Circus. The parents in that comic strip really loved their children. He put that image in my head and it stayed with me. I'd always heard that great art will cause people to burst into tears, but the only time it ever happened to me was when I was introduced to Bil Keane's son Jeff. As soon as I realized who he was, I just started bawling my face off because I realized I'd done it. When I shook his hand, I realized I had climbed through the circle to the side Jeffy was on.

“To me, they are family,” Barry finished, “—my soul family. That's why if someone says a word against The Family Circus to me, I will slug them so hard.”

Mommy is seated and hugging PJ and Dolly, and Jeffy comes up, saying: “Got some room left in that hug, Mommy?” Billy, carrying PJ around piggyback, says: “I’m practicing to be a daddy.” Approaching Christmas, Father brings home an evergreen tree, and Billy says: “Mmm! Now the house is beginnin’ to smell like Christmas.” Watching the leaves fall one autumn, Dolly wonders: “Why do trees take their clothes off when it starts getting cold?”

On a vacation, the family stands on a scenic overlook at the Grand Canyon, and in a flurry of speech balloons, the children register their appreciation: “Why are the rocks painted different colors?” “What time does it close?”

“For millions of readers,” said Michael Cavna, “Bil Keane reached out, day by reliable day, through the pure and distilled and comforting power of a single panel. The Family Circus may play out within its distinctive circle, but to many readers, the debut of its midcentury family felt like a keyhole, then a fully inviting window into a reassuring world—an approachable, guileless realm of broad grins, wide-eyed observation and the winking malapropism.”

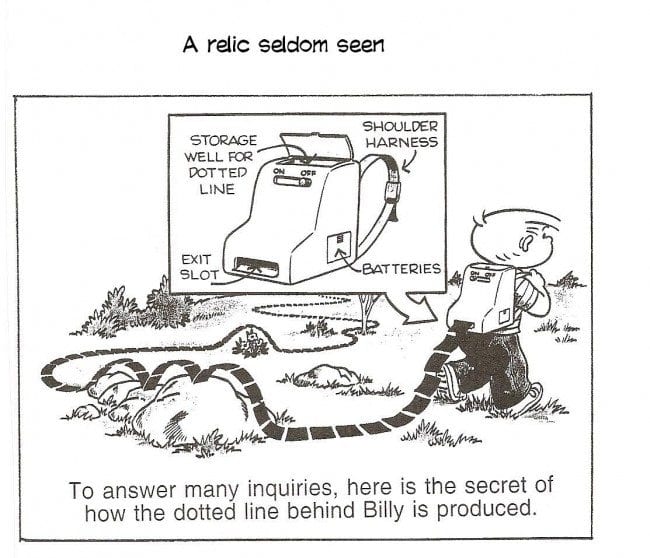

In the spirit of the latter, Keane added a couple of invisible characters—Ida Know and Not Me, gremlins who were always the ones who did the naughty thing and ended up getting blamed by the kids whenever something went awry. Another staple is Billy and his dotted line. Glen Weldon at npr.org remembered fondly:

A dotted black line followed Billy’s carefree peregrinations through the privet-lined, strangely carless, possibly post-Raptured streets of his neighborhood. Here, Billy dallies on a jungle gym. There, by the babbling brook, he catches polywogs. And all the while, that dotted black line follows him, jumping over tree stumps and skirting around barking dogs. It's impossible to read these strips, which depict a small child blithely wandering on his own through verdant backyards and quiet cul-de-sacs, without feeling a pang of nostalgia for a time before stranger-danger and Amber Alerts. But that's exactly what Keane was selling, of course. Because his dotted line always, always circled back to end where it began: On the doorstep of the family home.

Weldon also appreciated the sheer artistry of the dotted-line cartoons: “The Sunday dotted-line strips required a level of planning—and evinced a clean, meticulous draftsmanship—the daily strips never needed to. As I grew older, I began to appreciate the way Keane cheated the perspective so as to fill the entire panel with detail—even those places and objects farthest away from the reader's eye.”

Keane’s peers saw his genius: NCS awarded him the Reuben as “cartoonist of the year” for 1982. He also served as NCS President 1981-83. And “he never forgot his service in the Army,” wrote Terry Ponick at the Washington Times, “—and how important entertainment was for the morale of the troops. He frequently signed on to join USO tours” that performed before military encampments.

Keane’s peers saw his genius: NCS awarded him the Reuben as “cartoonist of the year” for 1982. He also served as NCS President 1981-83. And “he never forgot his service in the Army,” wrote Terry Ponick at the Washington Times, “—and how important entertainment was for the morale of the troops. He frequently signed on to join USO tours” that performed before military encampments.

He has also been known to offer advice to aspiring cartoonists: “Success can be found in four key words: Labor—hard work with unswerving dedication. Unique—Make sure what you do is different and original. Creativity—Let your imagination be your only guide. Knowledge—Know your subject. Know what the public wants and give it to them just before they know they want it. And, if you look at the initials of those four key words, they spell out a fifth: LUCK.”

Asked whether comics are “art,” Keane said: “The comic strip is a brilliant form of art developed in America and now imitated in every country. More people see and appreciate this art form daily than ever see the expensive paintings tucked away in museums. I’m proud to be exhibited regularly in over 1,500 newspapers, and to have my work hung on what I consider the world’s most prestigious art gallery: the refrigerator doors in homes across America.” But he’s never entirely serious for long: “Some cartoonists jot their ideas down on the back of an old envelope,” he once said. “Some talk into a tape recorder. I talk into the back of an old envelope.”

“Through the years,” Scott Craven wrote, “Keane stuck to his tried-and-true comedic formula of finding humor in everyday life. Whether it was poking fun at the same old Father's Day gifts to having Billy occasionally fill in as artist (resulting in pun-plagued sight gags on Sundays), Keane's relaxed style and simple themes endeared him to readers.”

Said Keane: “Everything that’s happened in the strip has happened to me. That’s why I have all this white hair.”

In the early 1980s, Keane’s son Jeff began working with him. “He agreed to do my inking, coloring, pencil sharpening, etc. for a 75-cent raise in his allowance,” Keane wrote, “—and will one day run away with the circus.” And so he has.

In the early 1980s, Keane’s son Jeff began working with him. “He agreed to do my inking, coloring, pencil sharpening, etc. for a 75-cent raise in his allowance,” Keane wrote, “—and will one day run away with the circus.” And so he has.

The father-son collaboration began with Jeff drawing Eggheads, a punny strip written by his father (“Did you take a bath?” “No, is one missing?”). It appeared in about 30 newspapers and ran for two years, after which, they quit. By then, Jeff had taken over the inking of The Family Circus from the previous inker, Bud Warner, who had been signed on in 1965.

Keane appreciated Warner’s work, giving him credit in reprint collections of the cartoon. A typical Keane accolade: “To Bud Warner goes credit for the very flattering things which have been said about The Family Circus finished art, most of which have been said by Bud Warner. It is a delight to work with such a fine gentleman, even though he is quite elderly. He was born five days before me.”

Jeff has been doing the panel solo for several years, although his father sometimes helps: “He’ll send me some roughs and some ideas and things,” Jeff told ICv2.com not long ago. “He’s not as involved as he used to be. [Since] my mom passed away, he’s been less hands-on. But he’s still there, he still reads, and he still tells me if I do anything wrong.” Jeff’s involvement in the strip pre-dates his inking apprenticeship by a couple decades. Born in 1958, by the time he was two, “Dad started to chase me around every day, begging that I do something funny.” Married since 1988 and with three “cartoon models” in the house, Jeff says, “I now chase those characters around every day, begging them to do something funny. So The Family Circus keeps going around in circles.”

At the death of Keane pere, cartoonists remembered him.

From For Better or For Worse’s Lynn Johnston:

I think my memories of Bil will echo those of so many others: he was generous, kind, talented and very, very funny. He loved his wife, Thel, so much that when she died, I think the light went out in his life. Despite the love and companionship of family and friends, he never really recovered. I wish that we could all have experienced such devotion in a partner. Bil was such a good example to us all—not only was he a hard and prolific worker, he was a man of honor, principle and integrity as well. He will be sadly missed.

Speed Bump’s Dave Coverly remembers Keane as

Such a gentleman. ... To me, and this was his greatest lasting influence on the cartooning community, he was a role model when it came to respecting the younger generations of cartoonists who followed him. He embraced the newcomers and made us feel more than welcome. In fact, he had a gift for making you feel like a peer, which is the highest form of respect any of us could want. He was one of The Good Ones.

At my first Reubens weekend, Keane came up to me, introduced himself, and said he enjoyed my writing about cartooning.

Non Sequitur’s Wiley Miller remembered Keane’s influence on him

Both as a professional and as a person. I do not measure up to him in either of those categories, but he served as a benchmark for me to keep working toward. You will hear from many saying what a good man he was, as well as being a great wit. I can tell you that these are not exaggerations—they're [not just] being polite in speaking of the departed. They are genuine sentiments and reflections of the man. You can't ask for more than that in life.

As Keane’s condition worsened over the last month, one of his sons was always by his side, Jeff Keane told the Associated Press. All of his five children and nine grandchildren and a great granddaughter were able to visit him the week before he died, Jeff said.

Of his last conversation with his father, Jeff said: “He said, ‘I love you’ and that’s what I said to him, which is a great way to go out. The great thing is Dad loved the family so much, so the fact that we all saw him, I think that gave him great comfort and made his passing easy. Luckily, he didn’t suffer through a lot of things.” At npr.org, Glen Weldon wrote: “As a man of devout faith, Keane likely suspected that his strip could provide comfort and hope to kids like Lynda Barry. Could he have imagined that his dotted-line strips might also have the power to send bored, broody, indoorsy kids like me down so many existentialist rabbit holes? Ida know.”