Hawkeye Vols. 1-4

Matt Fraction, David Aja, Javier Pulido, Annie Wu, Francesco Francavilla

Satellite Sam Vols. 1-3

Matt Fraction and Howard Chaykin

Sex Criminals Vols. 1-2

Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky

Deadpool Vols. 1-8

Brian Posehn, Gerry Duggan et al.

The Fifth Beatle

Vivek J. Tiwary, Andrew C. Robinson and Kyle Baker

I can't really think of a better way to categorize my kind of comics reader than "comics snob." By comics snob I mean the comics reader who, when introduced as a comics reader, instantly feels the urge to disavow any interest superhero comics. To the lay public this distinction will mean next to nothing. To the comics snob the superhero comic is the elephant in the room, who is your roommate, who happens to pay about 90% of the rent, and when you tell someone where you live they say, "Oh yeah, the Elephant House." Any self-deprecating use of the term "snob" will open you up to charges of humblebragging, but the term comics snob carries with it a tacit admission that there's something absurd about being a snob about comics. It's the absurdity of saying, "I don't read any of that superhero crap, what I like is Donald Duck."

The problem for the comics snob referred to herein is the superhero comic that's too good to ignore. The reference is facetious; good comics aren't a problem for anyone. The problem is this: Ignoring mainstream comics is easy. Steadfast resistance is the line of least resistance. Once the comics snob concludes there are mainstream comics worth paying attention to, he faces the fact that they publish an awful lot of mainstream comics, and to truly have a sense of what's happening in that part of the forest you'd have to look at a lot of trees. Lacking that kind of stamina all I can say about the state of mainstream comics based on the examples reviewed here is that an elephant sticks in the ground and is round like a pillar.

In fact, I'm uniquely unqualified to write about mainstream comics in any authoritative way. I stopped paying more than piecemeal attention at precisely the point where the X-Men had become the creative center of mainstream comics, a circumstance which in large part inspired me to get off the bus. In terms of modern mainstream comics history, this is like losing interest in the Bible when God decides that Adam needs a girlfriend.

When the superhero was born, super powers were a matter of being lucky or unlucky, or a combination of the two. Your planet explodes but you escape to a planet of pantywaists. You see your parents die but they leave you a lot of money. The wizard who knows the magic word likes the cut of your jib. You die. You find a hammer. You are the victim of a scientific industrial accident. Your dad is the Devil.

The mutant is far more relatable character. He or she is an outcast who finds that the thing that casts him or her out is actually a special ability that leads to companionship and adventure. Since by all accounts everyone who is not either the Homecoming Queen or the captain of the football team thinks of himself as an outcast, this gave the superhero a whole new dimension of reader identification. For my part, I processed this sort of thing as self-pity, and self-pity was to me what a bottle of vodka is to Tony Stark. I believe this quirk was also behind the absurd hostility toward Charles Schulz and Peanuts I often expressed in these pages.

This is the part of the program where the old fart is supposed to start telling you that comics were better in his time. I am unable to follow that script. My peak period of reading superhero comics coincides with the last days of the newsstand era, which is to say the time when they were still the cheapest reading matter you could buy. In the direct market era that followed comic books evolved into a Cadillac product, sold at a premium price to a discerning readership. The main difference is that you no longer see the staggering volume of mediocrity you did in my time. In those days professionalism was frequently synonym for hackwork. Regardless of how you feel about the purposes it's used for, you must admit that mainstream cartooning displays conscientious work and a high degree of polish, which represents a highly evolved consensus on how the superhero world ought to be presented. It also tends to create a barrier between superhero comics and the tastes of the comics snob.

All naturalistic adventure art sacrifices something in the way of individuality. The adventure cartoonist must conform to received notions of what looks heroic, what looks glamorous, what looks devious or hateful, what looks hypocritical, while simultaneously smuggling in the minimum amount of stylization and exaggeration that cartoon art demands. The dominant style of superhero is not in the smuggling business. Instead it pursues a realism that is almost surreal. As it happens, we find a perfect example of what I'm talking about in one of the Hawkeye collections to be discussed later on. As a bonus feature it reprints an early Matt Fraction story in which his main characters first meet, drawn by Alan Davis and Mark Farmer. Alongside the work of the eminently snob-friendly David Aja it's like they put a Lawrence Welk bonus cut at the end of a John Coltrane album.

If you have a style that leaves nothing to the imagination then you have to provide more than the reader’s imagination can. This provides nothing but technique. The effect is less like comics than hand-drawn fumetti. One thing I must allow to Davis and Farmer, however, especially in contrast with Aja, is that they create a world in which costumed heroes look natural. When the odd Avenger shows up in Hawkeye it looks like the local cosplayers have dropped by to show off their latest handiwork.

(Normally the only concession to costume in Fractions Hawkeye is a cap with an "H" that could be an Underarmor logo.)

Much as I normally don't care for the style, I do think Andrew C. Robinson used it to great effect in The Fifth Beatle. I'd picked it up mostly because Kyle Baker was involved. Baker's contribution turned out to be underwhelming, but Robinson shows that whatever its weaknesses in depicting fantastic material, photorealistic drawing has tremendous potential in bringing to life real life events that escaped the camera. See for example the rumored scene where Ed Sullivan negotiates with Brian Epstein through a ventriloquist's dummy:

This not only makes feel like a fly on the wall but that Ed Sullivan is in the room with me.

To the eye The Fifth Beatle reminds me of nothing so much as the hyper-realistic biographies of British war heroes Frank Bellamy used to draw for the Eagle. As a narrative it felt like the old village griot once more telling a beloved tale of our people, the one about the four lads from Liverpool who took over the world. As for writer Vivek Tiwary's argument for the talent manager as a creative force in his own right, I was less than convinced. While his packaging of the Beatles looks as fresh now as it did 50 years ago, it seems that the most important thing Brian Epstein did was stay out of the way, and after the first couple of years he dwindled into a footnote.

But this brings us to yet another problem for the comics snob: The cartooning style barrier I refer to is eroding. You would have to be a very blind man indeed not to notice how the range of acceptable styles in mainstream comics has expanded in the 21st century. It wasn’t that long ago that the style of a Paul Pope would have been considered entirely outlaw, but now is accepted into mainstream commercial comics as nothing out of the ordinary. Though a walk through a comics shop suggests that the kind of comic art I complain about still occupies the center ring, the tent is much bigger.

It's humor that makes superhero comics enjoyable to at least this comics snob. I've recently come to the realization that we make a mistake when we look at comics like Jack Cole's Plastic Man or C.C. Beck and Otto Binder's Captain Marvel as send-ups. Rather, they saw the humor inherent in the superhero concept and exploited it. Humor is challenging for the adult reader of superhero comics. Much of the joy of reading superhero comics when you're a kid comes from your ability to take them seriously. When you’re resolved to continue this pleasure into adulthood you must maintain an extreme degree of suspension of disbelief. Superhero comics face this challenge by keeping a very straight face indeed. A horse laugh in the wrong place undermines it. In an interview the comics writer Mark Waid recalled the dread he felt when reviewers started referring to a series of his as "fun": "'Fun' is a death word in this market."

There do exist even in this fun-shunning market a few titles that are humorous by intent, the most prominent being Deadpool. Though never one to shy away from a sick joke, I was never tempted to look beyond the words "Created by Rob Liefeld" until I heard it was going to be written by the comedian Brian Posehn. (Question for the better versed: Was Deadpool the last million dollar property to be surrendered to a company by way of work-for-hire? Last one that's spawned 200 issues or more of his own comic book, let's say. It seems it's a modern imperative among big money creators never to do this.) Posehn is joined his comrade-in-comics Gerry Duggan. I tried to do some online research about Duggan and found that he was (a) in Goldfinger, and (b) a different Gerry Duggan. It's little surprise that Posehn would seek the collaboration of a veteran professional. A comedian above all people would know the danger that awaits an amateur in an unfamiliar art form.

Posehn and Duggan's first collaboration was The Last Christmas, a limited series for Image. This was so unrelievedly grim that there wasn't even perverse joy to be gotten out of it. In a post-apocalyptic world Mrs. Santa Claus has been murdered and Santa wants to burn down every Christmas Village in the world. It doesn't mean to mock Christmas so much as take revenge against it. This practice run must have done some good, because the initial Posehn/Duggan Deadpool issues collected as Dead Presidents are everything you could expect of a Brian Posehn comic, and I presume at least equal to the Gerry Duggan standard. A patriotic but misguided wizard has reanimated the remains of every deceased President of the United States. His goal is to give the country the leadership it desperately needs, but it turns out that even Presidents come back to life as murderous zombies. Deadpool cheerfully dispatches them all with no regard for life, liberty or the pursuit of happiness except insofar as it entails killing zombie Presidents.

As the series develops beyond this initial storyline it becomes clear that Posehn means to be a mere celebrity guest writer, but to make his mark on the Marvel universe. (I presume that when it's your main line of work like it is with Duggan you always mean to make your mark on the given universe.) Pure comedy is reserved for the periodic "rediscovered inventory issue" in which Deadpool is inserted into various eras of Marvel history. The quality of these is variable, but the Deadpool's encounter with drunk Tony Stark is like something from the Valhalla edition of Harvey Kurtzman's Mad. In the main storyline Posehn and Duggan's main agenda is to humanize the character. I'm such a tourist here that my views are of little count, but it seems to me that humanizing Deadpool defeats the purpose. The premise of Deadpool is that he has been granted the power to instantly recover from any injury at the cost of being horribly disfigured, and is bitter as hell about it. He expresses his bitterness by being sardonically indifferent to the suffering of others and selling his services to the highest bidder. As Deadpool deals in the humor of insensitivity, I don't see the point endowing him with sensitivities. As he is an antihero, I would have assumed that the trick is to find a way to make his self-interested actions serve a virtuous cause in the end. One reason I liked the Dead Presidents storyline best is that it's the only part where the character is pursuing his day-to-day adventures. This I've always believed is the meat of any continuing superhero series. The subsequent Posehn/Duggan stories are instead intent on generating major life events – he discovers his true origins, he starts a guerilla war against SHIELD, he gets married, he engineers his own comic book "death." When not spread among day-to-day adventures such events lose the baseline that gives them an impact. Being there primarily for the wisecracks, however, I would not call myself unsatisfied.

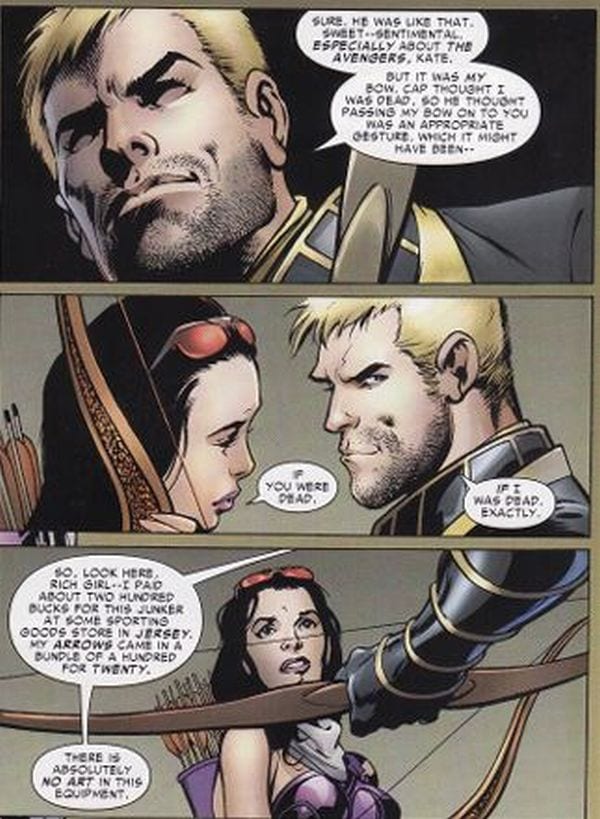

Of all current mainstream figures I find the hardest to ignore to be the writer Matt Fraction. For one thing he’s probably the wittiest person in comics right now – him or Kate Beaton. He consistently partners up with artists who make him look good. No comics snob himself, in interviews his reference points are as likely to come from outside as inside the mainstream, with no class distinctions. His dialogue sparkles, and his cleverness surprises. Of the three of his series under discussion the pure superhero comic is the best. He's discovered there's kind of humor that can be employed without compromising the dignity of the superhero, which is sophisticated humor. His version of Hawkeye is less like Iron Man/Captain America Avengers than John Steed/Emma Peel Avengers. He works this trick by exploiting the quirk of Marvel continuity that's created two Hawkeyes, one for each gender. That the Hawkeye of the title can be either one is its most clever trope. He-Hawkeye and She-Hawkeye banter and riposte through episodes that can be enjoyed as both action and slapstick comedy. He even comes up with new things to do with the trick arrows, which I imagine wins you the Prix du Hawkeye.

David Aja gets most of the attention – he is after all like Alex Toth with a good writer – the Hawkeye artists are analogous to the revolving vocalists of The Band, particularly because their styles harmonize. Let’s say, David Aja is Levon Helm, Annie Wu is Richard Manuel, Javier Pulido is Rick Danko, and I guess Fracesco Francavilla has to be Robbie Robertson because that’s what’s left. Or more to the point, Aja supplies the flashy technique and impressionistic action; Francavilla supplies the trauma when it all goes dark for an issue; Pulido and Wu take over for the more character-oriented segments Welcome as it is when Aja picks up the mike again, I found myself missing Pulido and Wu’s human touch. (Like Richard Manuel and Rick Danko I often find myself

This I think summarizes what Pulido brings to the proceedings:

Wu a somewhat scratchier version of the same thing:

Wu a somewhat scratchier version of the same thing:

Now about that “Futz.” Here’s a tip: If they don’t let you say fuck, don’t use fuck substitutes. It didn’t work for Norman Mailer, it didn’t work for Chester Himes, and it won’t work for you.

The main plot thread in this series is He-Hawkeye's campaign to preserve his Bedford-Stuyvestant Shangri-La of low income polyglot urbanity from the forces of gentrification. When he finds Russian mobsters attempting to evict his neighbors in order to turn the property into some, He-Hawkeye buys the building himself. (His superpower is apparently the ability to make big bags of money appear.) Ten issues in the tone suddenly changes from Pocketful of Miracles to The Act of Killing. The heads of Marvel gangland give the Russian gang boss the Hawkeyes He and She have been bedeviling a license to kill. Suddenly we're in a world of heartless death machines in clown makeup bred for murder from childhood in the killing fields of Eastern Europe. We soon learn that He-Hawkeye's lovable dullard neighbor was not merely a comic relief character but a lamb being fattened for the slaughter. Soon the poor sap lies dead in a pool of pathos. The introduction of Killy the Clown is not just a wrong note, it invalidates the whole concept. If He-Hawkeye brings violence down on his neighbors that he can’t protect them from he has no business playing policeman. The number of lives worth sacrificing so people don’t have to move is zero.

And the menace isn’t even genuine. Killy the Clown turns out to be just as ineffectual as the rest of the Keystone Krooks have been. (Seriously, all these “mobsters” need to be Star Wars storm troopers is white helmets.) Especially considering that this is supposed to be a diversion from the main Avengers storyline, there’s no reason the knockabout tone couldn’t have been maintained throughout. At the risk of being pedantic, it seems strange that Fraction invokes Rio Bravo for a climax in which the tenants join the heroes to defeat the mobsters when in the movie itself the John Wayne character expressly does not want the help of the townspeople because the gunmen would only gun them down. (I’ve always suspected it was Howard Hawks’ answer to High Noon.)

Things having gotten hot in New York and He-Hawkeye's infidelities having gotten hard to take, She-Hawkeye in the meantime crosses the country to give Fraction an opportunity to try out his L.A. material. Los Angeles has always attracted more people than it suits, and even satisfied customers will seldom find precisely what they were expecting. Since revenge is one of the three main reasons people write, this has lead to a literature of malediction summed up in the title of a Horace McCoy novel: I Should Have Stayed Home. Fraction could just as easily have stayed home himself, since you could visit the Los Angeles depicted in the issues collected as L.A. Woman on your iPhone. There is from what I can see only one insight from lived experience: He is absolutely correct that no who lives in Los Angeles has ever eaten at the restaurant in the Theme Building of LAX, and neither do they know anyone who has ever eaten at the restaurant at the Theme Building at LAX. The rest is primarily cobbled up from The Rockford Files, John Frankenheimer's Seconds, and Philip Marlowe as played by Elliot Gould in The Long Goodbye. It boasts not one but two Magic Negroes. As a bonus they're gay Magic Negroes, so you don't just get black people who have nothing better to do with their time than help white people but gay people who have nothing better to do with their time than help straight people. These fellows must be on-call for chauffer duty as She-Hawkeye tries to get along without a car in Los Angeles without ever getting on a bus.

The genre that trips Fraction up is not superheroes but crime. Take for instance his fictionalized version of the Brian Wilson story. Naturally, when you fictionalize real events you’re entitled to make things up, but you abuse your privileges when your fiction trivializes the fact. In Fraction’s hands the story of an emotionally fragile young man of talent buoyed along for years by an unbroken string of success who completely loses his nerve when he hits his first creative block is rendered into a simple-minded tale of victimization. But then, the reality of the situation is probably not a comfortable notion for a prolific popular artist in his own right.

All of this is not to say that Fraction's second hand goods aren't cleverly chosen and cleverly juxtaposed. Particularly winning is the villain's henchmen, a Busby Berkeley chorus line of bellboys who initially appear in a hotel and then recur in the same costumes in every other setting. Or how the Dr. Eugene Landy character in the Brian Wilson section is played by the Henry Gibson character from The Long Goodbye.

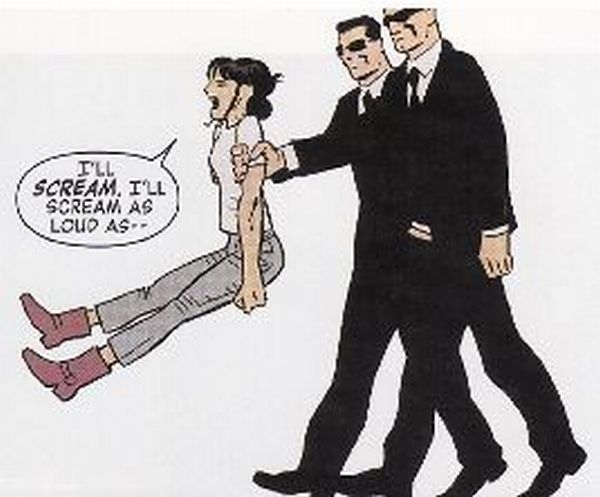

I fear however that the strongest impression I was left with from L.A. Woman is the impracticality of a superhero who isn’t bulletproof. Recall that the superhero was created as an emotional response to the criminal beyond the reach of the law, and the more general feelings of helplessness that represented. The organized criminal when he does not buy official protection or hide his crime behind the civil rights protections of the law, defeats justice through simple violence. He meets his match in an incorruptible nemesis who is above the law, sees through walls and laughs at tommy guns. In L.A. Woman you have a heroine who causes all sorts of trouble for an impenetrable criminal organization that kills with impunity, while riding around town on a bicycle protected by nothing but a sleeveless blouse.

Sattelite Sam is just too damned busy. Its central plotline is enormously promising. It's the dawn of television. Carlyle White, star of a popular Captain Video-type science fiction is found dead in a cheap room he's rented for illicit activities. His son Michael White, played by that omnipresent figure in the Howard Chaykin stock company, The Guy Who Looks Like Clark Kent, is recruited to take his place. Among his father's personal effects he finds boxes and boxes of photographs of nearly-undressed women clearly taken by the deceased. He sets out to trace his father's secret life. Now that's some rich, Oedipal stuff there. The problem is that it gets lost in an overabundance of subplots. There's the TV pioneer who's fighting a losing battle for FCC approval of his superior technology over that of the politically powerful Paley and Sarnoff. There's the FCC commissioner he's courting, who is also running for office on a red-baiting platform and carrying on an affair with the TV pioneer's wife. There's the TV pioneer's wife, who is carrying on affairs with just about everybody with the tacit acquiescence of the TV pioneer. There's the closeted gay scriptwriter threatened with exposure because of his habit of having sex in the workplace. (But then, everybody in Sattelite Sam has sex in the workplace.) There's the Aimee Semple McPherson-style sexy televangelist whose main purpose seems to be modeling vintage lingerie. This purpose she shares with nearly every presentable female character in the comic. There's the Ernie Kovacs-type character who’s there because there has to be an Ernie Kovacs-type character, and who is a black man passing for white because no civil rights issue can go unaddressed. Not to mention the cast and the crew of the TV show, heels one and all and each a womanizer or man-izer in their own right.

In short, Fraction has bitten hard by the James Ellroy bug, and the 1950s are the wet underside of a rock whose every grub must be scrutinzed. The problem isn’t that these plotlines are bad but that each one could have taken up a series of this length by itself. Taken together they make Satellite Sam so exposition-heavy that Howard Chaykin is often limited to talking heads. In a way it's giving good value, because you have to reread the thing one or two times to figure out what's going on. The best part of it are Fraction’s capsule recaps of each character’s storyline, which are indispensable even when it’s read in collected form. Inside this fat story is a thinner one struggling to get out.

The central plotline concerns the elder White’s plot to start his own personal television empire by squirreling away kinescopes of Satellite Sam. This indeed mystifies the reader. What earthly good can this have done the elder White, the reader wonders, if he didn’t own the syndication rights, and why he would have to sneak around if he did. For extra credit the reader might wonder how much of a television empire you could have built on kinescopes of Captain Video. It turns out that he had some kind of blackmail film (blackmail being the universal solvent of Satellite Sam). The moral of the story: It’s better to have a mystery that seems fascinating for 14 issues with a popcorn fart of a solution in the 15th than what seems an idiot plot for 14 issues and an excuse in the 15th.

As a final note, the Satellite Sam collections have got some of the ugliest cover art I’ve seen on a professionally produced comics. If they’re intended to evoke Eric Stanton or something like that they either go too far or not far enough.

What brings me up short with Sex Criminals is Fraction's unwillingness to face the implications of his premise. Now, I realize that when your creator-owned comic is the kind of mega-hit that has retailers planning their business models around a new issue, like Christmas; when it is being adapted for television, a medium to which the premise is if anything better suited; the last thing you're going to do is look for ways to improve it. Rather, you are going to take the greatest care not to mess up a good thing. There are many good things in it. The villains are as comically fubsy in their killjoy way as the heroes are in their sex-positive thieving. Chip Zdarsky has a subtle comic touch and a knack for depicting characters in the upper middle class of attractiveness. And yet, its shortcomings go a long way to show why Fraction's comics constantly threaten to be better than they are without carrying out the threat.

Suzanne and Jonathan, the protagonists of Sex Criminals, independently discover that time stops for everyone but them when they sexually climax, then discover that they can jointly enter this realm of suspended time when they climax together. They resolve to rob the evil bank at which Jonathan is unsatisfactorily employed and which is going to foreclose on the public library Suzanne loves, and use the proceeds to save the library. It's difficult to believe that Fraction doesn't know how public libraries are funded, or who decides whether their branches stay open, move or close, or that when a branch closes the books are not destroyed but are distributed through the system. The logical thing would be to make Suzanne a bookstore owner stealing to stay open, like Grofield and his regional theater in the Parker books. The only reason I can see for Fraction to tie himself in knots is to absolve his heroes of any suspicion of self-seeking. You ask yourself, why stop at a public library? Surely he could have worked in an orphanage if he really tried. In comic book terms, a character who when granted gnarly powers uses them to commit crimes is technically speaking a villain. You are at least dealing with characters with a little larceny in their hearts. If you’re saying that anyone would steal if there were no possibility of capture then you’re saying something about the human race.

None of the defects I preceive seem that difficult to remedy if they were recognized as defects. They all stem from a failure to understand what the heart of his story is. In Hawkeye it's the question of what happens to your relationship to the community you’re trying to preserve when you change from a neighbor to a benefactor. In Satellite Sam it's what happens when the protagonist puts on his father's pants. In Sex Criminals it's the question of what it means to be a criminal. There's nothing to compel him to address this issue. It’s not going to keep anyone from reading his comics, including me. The question is whether he wants to be half-assed for the rest of his life.