Go here for part one.

On January 10, 2011 the Association employees went to Menu’s office and announced that they were going on strike and would occupy the L’Association building until their demands were met. They wrote a press release detailing their grievances and a demand for a general assembly to be held at once. This was followed by an online petition that was circulated widely in French comics circles and signed by almost 1,500 people, including prominent creators and publishers, as well as a blog set up by fellow publisher Jean-Louis Gauthey, of Cornélius, on which were published updates, announcements, and art sales and events in support of the employees.

The way L’Association is set up has never been entirely clear, even to its founders, and the lack of real structure proved to be a serious problem in solving the problems prompted by the strike. In brief, the publisher has drawn intellectual and practical support over the years from a slowly accreting roster of so-called “honorary members”—comprising assorted creators, colleagues, and friends chosen cumulatively over the years by the founders. Though never formalized as a body within the structure, the more or less common understanding during the crisis was that any new directorial board would have to be chosen from its ranks.

Furthermore, the French law concerning grassroots organizations entitles each member to vote for a given organization’s board at its general assembly. The employees thus hoped that by calling a general assembly, the question of how to proceed could be put to the entire membership for the first time in L’Association’s history. To this purpose, they tried to encourage as many supporters as possible to pay the €15 membership fee and join L’Association. Menu and the directorial board however did not share this interpretation of L’Association’s constitution and resented what they perceived to be an encroachment by the employees on decisions that were theirs to make.

As part of their campaign, the employees reached out to the estranged co-founders, three of whom—David B., Trondheim, and Killoffer—decided that it was time once more to get involved and joined up as ordinary members. Trondheim explains how they had followed developments at L’Association from afar for years, seeing how Menu had fired or forced several former employees to quit, one of them while she was pregnant; how Menu had stored a large print run of a sketchbook by Jacques Tardi published on his own at the expenses of L’Association; how he had initiated the use of stickers to avoid having to print barcodes on the books, costing the publisher €15,000 a year; how he had spent €32,000 on the development of a website since 2007 without it ever materializing; and how he had failed to anticipate the collapse of the Le Comptoir des indépendants, incurring the substantial loss already mentioned.

“David and I discussed whether it might not be best just to let L’Asso die," Trondheim says." We could then recuperate our books from the publisher and be done with it. But thinking about it in a less selfish manner, we recognized that it was still a viable platform for the publication of high-quality work, and that a lot of creators and books would find themselves without the support they had previously enjoyed if it disappeared. And that the employees would be out of a job.”

As indicated, the situation had by this time elicited the attention of the wider French comics industry, and certain players close to L’Association decided to get involved. Gauthey, publisher at Cornélius—another bastion of independent comics in France, founded in 1991—played an important organizational role in addition to managing the blog in support of the employees. “It is very important for the microcosm of alternative publishing that L’Association stays strong and visible," Gauthey says, summarizing his rationale (which is explained in greater depth in an open letter on Cornelius' website). "It is very important for all of us. Although the market is small, it is there, and L’Association is like a leader. It is a powerful force in the market. If L’Association dies, I think the market will be diminished dramatically. So it was in my interest as a small publisher to protect and help my competitor and partner stay strong. In addition, I had moral reasons to get involved, because all of those people are my friends and I was shocked by Menu’s decisions."

An initial attempt at reconciliation happened on January 12. Part of the agenda was the imminent comics festival in Angoulême, where L’Association traditionally maintains a substantial presence, with a large booth from which they make a significant part of their annual income. Menu wrote in his “Bandelettes” that the employees signaled that they were ready to work at the festival after being promised a meeting with L’Association’s accountant Camille Lawson-Body to go over the books together. This meeting never happened however, wrote Menu, because Lawson-Body’s father passed away necessitating his leaving the country for a while.

With Angoulême looming, the direction decided to hold an emergency assembly, which took place on January 22. Menu described this as a “gathering of sages,” comprising a select number of friends and associates, including L’Association’s lawyer as well as Menu’s mentor and former boss at Futuropolis, comics publishing legend Étienne Robial. The treasurer, Laetitia Zucarelli, who was siding with the employees in the conflict, decided to invite them along too, and further opened the doors to a number of other interested parties, among them David B., Trondheim, Killoffer, and Sfar.

Menu, who was troubled by the efforts of the employees to take their “internal” grievances public and who saw in their efforts to recruit new members an attempt to push him out, seems to have regarded this meeting as a way of consolidating his control of the publisher. It is unclear what exactly he was hoping to achieve, but the presence of the employees and his co-founders, who questioned the validity of the assembly to make decisions and generally rained criticism on the direction, only resulted in worsening the deadlock. In the following days a few more attempts at addressing the situation were made by the direction, but none of them to the satisfaction of the employees. Menu says he attempted a last-ditch effort to negotiate a “truce” on the day before the festival, which was also rejected.

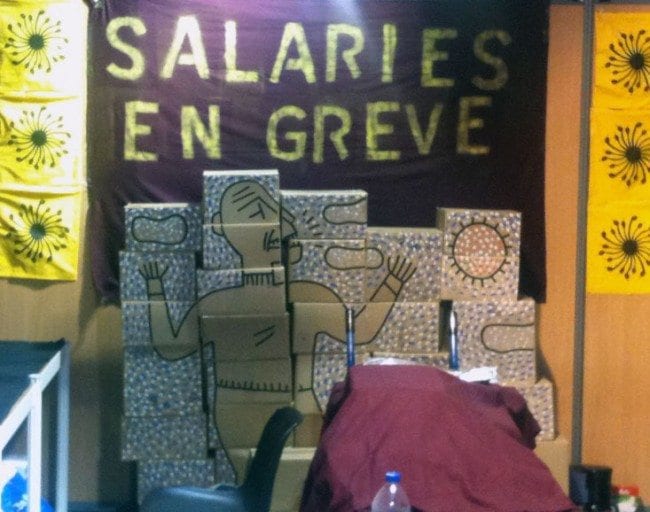

The result is well known to anyone who attended the Angoulême festival on the weekend of January 27-30. L’Association’s booth at the head of the centrally situated, alternative-focused “Nouveau Monde” tent was empty for most of the festival, save for a big sign reading “EMPLOYEES ON STRIKE.” The only reading material available was a pamphlet prepared by the employees, describing their grievances. It was a stark manifestation of crisis. At the comics website he runs, du9.org, industry critic Xavier Guilbert described it as “a kind of black hole at the entrance of the Nouveau Monde tent, which darkened the mood and fed the conversation of everyone.”

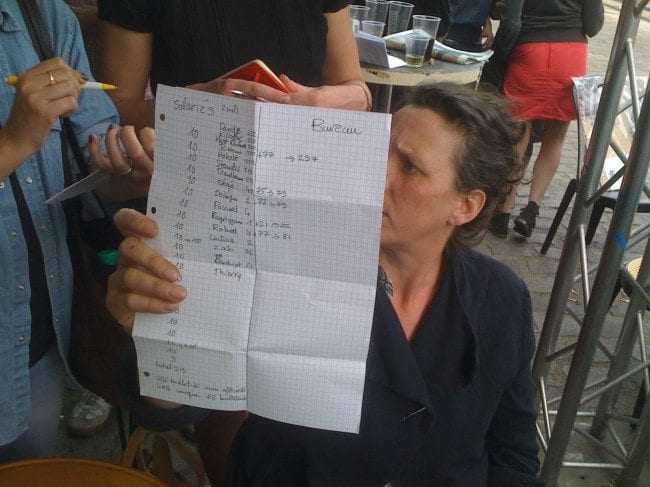

Facilitated by a number of mediators, a meeting between Menu, Chipot, and several of the employees took place on the Friday of the festival. The employees were shown the budget for 2011 and promised that the list of candidates (or "honorary members") for at the upcoming general assembly would be put together jointly. Partly in acknowledgement of this and partly to support the Association creators present at the festival, the employees decided to open the booth for a few hours on Saturday.

None of this changed the fact that this was a public relations disaster for Menu and the direction, as well as a very costly affair for L’Association, because of lost sales as well as the money wasted on buying exhibition space, shipping books, booking hotel rooms, etc. Asked about this undeniably damaging consequence of the strike, Carmela Chergui counters, “We had promised that we would stop striking the moment we had a response to our demands. We therefore went to the festival with all the material necessary to pick up work again. If the direction had responded to our demands on the first day, we would have opened the boxes and put the books on display. And in any case, the money saved on us not being paid in large part makes up for the loss of sales in Angoulême.”

After this shock to their system, Menu and the direction made another overture to the employees. On February 3—still according to Menu’s “Bandelettes”—president Partricia Perdrizet followed up the promises made at the festival and sent them an e-mail conceding to all their demands. They refused to negotiate.

Chergui explains that this was in part due to their still not having been shown the numbers that they had demanded to see, but more importantly stemmed from a disagreement over how to run the general assembly. While the employees wished to see every author connected with L’Association, as well as other “friends” of the publisher—a list of 147 people considered as candidates in the election, Menu would only agree to “a shorter list, comprised in large part by people we didn’t know. For us this was another way of telling us that our opinions didn’t count and that our strike was pointless.”

It would also seem, however, that they were also stalling for time in order properly to mount their defense. They had now hired a lawyer and organized a meeting in his offices on February 8, attended by the directorial board as well as Menu and Lawson-Body (the accountant), and mediated by two cartoonist friends of L’Association, Gila and Emmanuel Guibert. Here, finally, the numbers for 2010 were presented and discussed. From this it emerged that the decision to fire the employees may have been premature, although the accounts given by Menu and the employees differ considerably. In any event, any layoffs were postponed till after a general assembly could be held. A date, March 5, was set for it and the employees decided to end their strike the following day, February 9.

Although the immediate crisis had thus been defused, many problems remained and were allowed to fester for the next three weeks, during which several more meetings were held under the auspices of Gila, Guibert, and other mediators. Of central importance was the issue of how to define the honorary membership for the general assembly, and despite the previous agreement that the two parties were to compose the final list together, assisted by their respective lawyers, no such thing happened.

During these negotiations, the employees and their supporters, including David B., Trondheim, and Killoffer, further proposed that the general assembly should institute a new editorial committee, returning L’Association to its roots as a collaborative effort. Menu saw this as an unprecedented encroachment by the employees. In his “Bandelettes,” he wrote, “[the employees] convey the impression that they want to control everything at L’Association, extending into areas far beyond their prerogatives, wanting to influence even the editorial direction.”

All this shuffling resulted in the general assembly being postponed by over a month. It was eventually held on Monday April 11. At 10am, a couple hundred people— including the directorial board and the employees, Menu, David B., Trondheim, Killoffer, Mokeït, Gauthey, and a number of other creators and comics professionals—showed up at the venue on the Canal St. Martin in Paris’ tenth arrondissement. The mood was tense with anticipation.

It quickly became apparent that no agreement on how to proceed had been reached. Perdrizet took to the stage and opened the meeting by stating that the order of the day would solely be the election of a new seven-member directorial board, with other issues to be decided upon at a later assembly, and—to great consternation in the room—that only the people nominated by the direction would be on the ballot.

With her she had their candidates—a group that, in addition to herself, Chipot, Zuccarelli, and Menu, included Futuropolis founder Étienne Robial, as well as a number of people only indirectly tied to the comics industry: Dominique Radrizzani, a Swiss museum curator; Guillaume Dégé, an arts professor at the École Supérieure in Strasbourg; Barbara Pascarel, bibliographer and manager at the College of Pataphysics (an important philosophical precedent for Menu’s Association); and Stéphane Distinguin, president of an IT company and of an innovation agency, FaberNovel, which had audited L’Association to reportedly mixed results a few years previously. Menu then argued that the alternative list provided by the employees, which quite simply comprised the seven founders, was illegal and would have to be dismissed. He further emphasized, as he had in his “Bandelettes,” that he be judged on the basis of his incontestably significant achievements as a publisher.

Needless to say, this caused outrage among many of the attendees. David B., Trondheim, Killoffer, and Mokeït mounted the stage to provide counterweight to the direction and their candidates. After a heated discussion, with much back and forth between supporters of the two camps—including a passionate defense of Menu by Robial—it was agreed that legality be damned, the two lists would be fused and voted upon. A half-hour recess was then called.

Once the assembly was again in session, Perdrizet and the direction attempted one last time to make the argument for the unique legality of their list. This was quickly shouted down and the vote was finally taken, resulting in the election to the board of all seven co-founders: David B. (president), Killoffer (secretary), Trondheim (treasurer), Mattt Konture, Menu, Mokeït and Stanislas, though the latter subsequently decided not to accept the position.

For Menu, there is still a problem of legality. “The list that was voted on was not official. And in the case of [the law concerning non-profits] it is very difficult to say whether an unofficial list can be [voted upon], so for now, we’re kind of in between, because the new directorial board acts as if it is legal, but it’s not completely legal. The other problem was that the old directorial board hadn’t held a general assembly for four years and thus wasn’t really legal either. So it’s a mess.”

Asked why they had not held a general assembly he responds, “because L’Association is kind of a mess. In fact, we used to hold assemblies simply in order to have parties, with bands, exhibitions, and so on. That was really the object of having assemblies, not to make the people vote. What the employees were asking was for an election where all the members would vote, and in its twenty years that has never been how things worked at L’Association.”

The question of honorary members was itself problematic. “The honorary membership was just a list of friends, authors, and people who received our books for free," says Menu. "It wasn’t legal either. Juridical nonsense. The problem was that in the time of crisis, this nonsense became, really… bullshit.”

Legal or not, the result of the election was received with relief by many observers. The crisis was over. Further welcomed was the more or less immediate decision by the new board not to lay off any employees. L’Association will continue with a salaried staff of seven. (Production manager Nicolas Leroy has left his position and has been replaced by Christophe Bouillet, a volunteer at L’Association from the early years). Ahead lay a difficult process of reconstitution and compromise.

—————

The election over, attention turned to the financial problem at hand. Apparently, and in stark contrast to the announcements made by the former directorial board and Menu, L’Association is in fairly good shape financially. There is reportedly around €500,000 in its bank account. “Menu and the directorial board wanted to project the idea that there was a financial problem in order to justify the layoff of staff. Yes, there has been a general reduction in sales, but that only means we have to economize a little,” says Trondheim.

In addition to settling on a financially viable output, this means getting rid of stock, eliminating the barcode labels Menu had been using, and terminating the costly website development contract—in its place, a new, very bare-bones, blog-style preliminary L’Association website was launched on July 8, with the opening of an more elaborate site announced for November 15, becoming the publisher’s first ever official presence on the web.

“It is true that L’Association’s sales in general have fallen, like that of all publishers, small or big," Gauthey elaborates. "It’s a general problem that sales are down, in France as well as in the United States and Asia. There are other small French comics publishers who are experiencing problems related to this, like Les Requins Marteaux or Cornélius. We are all familiar with this problem. L’Association’s good fortune is that it has a deep and strong back catalog that continues to generate sales and secures its survival. The difference between five years ago and now is that five years ago, L’Association was rich, very rich. Today, L’Association has a stable economy that enables it to pursue its publication program normally, as long as no one does anything crazy. It is in a better position than all the other small publishers."

Menu does not recognize this analysis. “There is still money on the account, but there isn’t money for more than two or three years," he says. "The numbers show that every year we are losing money. It’s very simple to understand. It’s impossible to continue like this. Asked how there could be such a large discrepancy between his and the new board’s interpretation of the numbers, he replies, “The problem is that Lewis and David don’t know anything about this. They haven’t been around for the past five years and are just listening to the employees who have their own interpretation of the numbers. They think it’s still the good times, but no, it’s not. They are going to have to deal with these very real problems.”

It seems inevitable that such differences in outlook would result in a real challenge to the new board. The optimistic notion, prompted by the election, that the band was back together again rather unsurprisingly proved to be wishful thinking. On May 23, Menu left L’Association.

“I hadn’t spoken to some of them, like David and Lewis, for five years, so that was complicated. I tried and was happy to plan new publications, but as soon as we got down to details, I realized that it was impossible for me,” Menu explains. “There were two problems, both mixed up—one was with the employees: I was the ugly, horrible boss; the other was with the founders: I was the bad person who just wanted power and so on. And when they came together in a kind of coalition, it was too hard for me. I was really fed up with that shit.”

Trondheim says he expected them to be able to collaborate, but describes Menu’s demands as unacceptable. “He wrote us an email asking to be confirmed as editor-in-chief and head designer, demanding an annual salary of €60,000, and that we would not be allowed to vote for the editorial committee [that we were going to form]," Trondheim says. "He was OK with us bringing in new books, as long as we kept quiet.”

David B. seconds this. “His conditions were that he would retain full editorial control and be guaranteed a salary," he says. "Lewis and I told him that it was out of the question. We hadn’t returned just to shine his shoes and to watch him secure for himself even more money on the basis of our efforts, which are all work done for free. Once again, Menu made clear his motivations: power and money. I know he was furious at our refusal, but it’s too bad that he was unable to draw a lesson from what had happened and couldn’t accept that things have changed.”

Illustrating the acrimony of the split is the fact that Menu, who had initially planned to finish the books he was already working on at L’Association, soon after found that a new lock had been added to the door to the publisher’s headquarters at 16 Rue de la Pierre Levée. To him, this added insult to injury and settled matters: “If they hadn’t done this shitty thing with the locks, I would have tried to stay on good terms with everybody, but now I don’t know. We’ll see.”

“During the strike and after our return to L’Association there have been certain manifestations of hostility," David B. explains. "A slogan hostile to the employees was written on the wall outside and the address plaque was removed. After discussing this and considering Menu’s chronic alcoholism, we decided it would be better thus to avoid unpleasant surprises. Menu has free access to the building when we are there and can work on the books as he likes. We have let him take away the computer he used for work, which belongs to L’Asso; we let him take the pyramid [art object] which also belonged to L’Asso and on which all six of us worked… this is just another case of bad faith on his part.”

Bad faith or not, Menu is now definitely out of the picture and the new directorial board is planning the way forward. One of their first decisions was to expand the newly established editorial committee to include younger authors close to L’Association. Joining David B., Killoffer, Mattt Konture, and Mokeït are Etienne Lécroart, François Ayroles, Jochen Gerner, Alex Baladi, Florent Ruppert, and Jérôme Mulot. (Trondheim has exempted himself because of his editorship at Delcourt’s “Shampooing” in order to avoid a conflict of interest). The ambition seems similar to the sentiments expressed by Menu a few years ago when he resurrected the Lapin anthology: to mitigate the older generational dominance at L’Association.

One thing that will be different is that the editorial committee will not be working in accordance with an ideological substructure or framework of the kind Menu formulated. “This was a very important question,” explains Ruppert. “For François and I at least, it was unclear whether we were supposed to choose books [to publish] that we just like, or books that we think are good for L’Association. We asked the founders about this—was there a clear statement on how we should choose?—and they said that it is very important that we listen to our hearts. That’s how they always did it, and that’s how it should be done. We use our intuition… I don’t think that is actually true, however,” he continues, “when you’re an editor at L’Association, I think you follow the tradition. I know and feel which books are fit for L’Association on the basis of L’Association’s catalogue.”

Trondheim explains that L’Association will now return to a less radical editorial direction and seek out some of the historical authors that Menu alienated—Blutch, Sfar, Delisle, etc., but at the same time emphasizes that it is “out of the question that we’ll publish mediocre work just to increase sales.”

While the new direction will surely bring back certain people who had left, the concern remains that the conflict may have caused a crisis of confidence with others. Menu says, “I think it’s a real problem that this strike has given L’Association such a bad image that a large part of the authors are confused and don’t want to continue [with L’Association]."

Trondheim recognizes this. “It’s hard to hand over your book to a publisher that behaves badly," he says. "So even though Menu is now gone, we have to communicate our goals and prove with our publications that we are capable of keeping alive the Association brand.”

As for immediate publishing plans at, Menu has left a schedule that runs until March 2012, which the new direction is going to honor. After that, Ruppert explains, they will have a new book by L’Association mainstay Vincent Vanoli, as well as one by David B. Poignantly, Trondheim is also bringing to L’Association the book he has been editing on the early days of the publisher, which includes contributions by David B., Killoffer, Joann Sfar, Mokeït, Jean-Yves Duhoo, Jean-Louis Capron, Charles Berberian, and Stanislas. Trondheim first announced this project around the time of Menu’s twentieth anniversary celebrations, implicitly positing it as a counterpoint to his discourse, with planned publication under “Shampooing,” the imprint he runs at the mainstream house Delcourt.

In addition to these new books by established creators, the best stories serialized in Menu’s resurrected, young cartoonist-focused Lapin will be released in book form once they are ready. The anthology itself will undergo yet another change in concept; Ruppert explains that they are thinking of making it an annual publication and of releasing it in broadsheet format. And he emphasizes that they are actively recruiting young talent: “We’re looking for the new black.”

Menu himself is moving in a new direction. On August 31 he issued a press release announcing his new publishing venture, L’Apocalypse. Named after an initial, discarded title for Labo, the anthology that started it all, and run in collaboration with its publisher, Menu’s mentor and Futuropolis founder Étienne Robial, publication will start next year.

“I don't want to publish just comics: books of drawings, texts, book art, all kinds of work will be part of our catalog," Menu explains. "And a large department of records, vinyl obviously, will be set up. It will thus be more of a place to transfigure the 'progressive erosion of boundaries' so important to the defunct anthology L’Eprouvette, than just another new 'comics publisher.' L’Apocalypse, then, will fit my polymorphic aspirations better than L’Association, where I respected the fact that it was a comics publisher, even when I was there alone, despite the fact that the status I wrote for it as early as 1990 announced an 'erasure of the boundaries between different forms of expression.' L'Apocalypse will be rock’n’roll. And under the sign of the Double.”

He writes that it is too early to announce specific publications, but that several artists formerly published by L’Association, as well as many others, will join him. David B. acknowledges that L’Association will see some creators go: “We know that Marjane Satrapi will not work for L’Asso and we doubt that Dominique Goblet and others close to Menu will want to.” Satrapi has made no public statements on the crisis at L’Association, but the fact that she has remained with the publisher through thick and thin since the first volume of Persepolis came out in 1999—surely turning down lucrative offers from bigger publishers along the way—speaks volumes. Furthermore, those more steeped in industry lore will know that she fell out with her former mentor David B. years ago and will be familiar with her strong loyalty to Menu. Her choice, thus, should come as no surprise:

“Marjane is going to follow me, of course,” explains Menu. “Before all this happened, we talked about a new edition of [her third book] Chicken with Plums to be published when the movie [based on the book] comes out in October, but now, with all this shit, there will be nothing. She doesn’t want to publish the same book with two publishers and I think she’s right. She doesn’t want to work with this new directorial board, and she’s not the only one.”

David B. is fairly sanguine about this. “Others, who said they would quit L’Asso if Menu and his clan won out, are now staying with us," he says. "And we’re happy about it.”

-----

So what have these problems meant for comics? Is this a story of dashed ambitions and a shift away from a radical conception of comics as art, as certain critics with axes to grind against Menu and L’Association have suggested? Or do the financial factors that precipitated the crisis reflect on a micro-level the woes of a book industry experiencing a sea change in how people buy and read literature?

It would seem that the latter is the case, although it is also undeniable that the new wave of comics ushered in by L’Association and their peers has crested, giving way to a much-changed comics landscape. Many of the hard-fought battles initiated by the nineties pioneers, in France as well as internationally, have been won. Comics is a more diverse and dynamic art form than perhaps at any point in its previous history. Young cartoonists do not have to work in opposition to as palpable an existing order as their predecessors. The challenges now are elsewhere, and often digital in nature. The kind of experimentation promulgated by L’Association in its first decade has opened multitudinous avenues of exploration for artists, and is now taken for granted. It is no longer radical.

This seems to be what Menu was reacting to, both with his theoretical radicalization and his drastic decision to cut staff and make L’Association a smaller, leaner operation. But while he in a sense has stuck to his avant-garde roots, his former more commercially successful partners have largely adapted to this new state of affairs. Less apprehensive of its consequence, they have found ways to continue their work and even thrive.

Despite what they have been saying, this difference in outlook in L’Association’s leadership—which now functions without the stubborn and combative, but also challenging and even utopian dialectic provided by Menu—cannot help but change it as a publisher and agent for change in comics. At the same time, however, it appears to have been the only possible and indeed constructive outcome of the crisis for the publisher, but perhaps also for the new reality of comics that L’Association helped bring about in the first place.

More than anything, however, it is a human story of ambition and conflict. When Gauthey says he got involved for moral reasons, it highlights what was at stake in the immediate term—something also described with candor by Chergui in her account of the strike and what led to it. L’Association was built upon the flawed governance of seven artists who neglected to formalize their collaboration in ways that would help them weather the conflicts that emerged between them. Says Menu, “As we became older, it became really hard.”

Xavier Guilbert of du9.org sums it up succinctly. “One thing that jumps to mind about this fucked-up situation they’ve gone through is the question of history and legacy," he says. "This question is, in my opinion, at the core of the whole thing, far more than the question of financial health or the idea that the market would have won against the utopians of alternative bande dessinée… A collective seems all good and fine when you’re young, but faced with middle age some egos may have been wanting to take over and claim some of that collective fame for themselves. More of a mid-life crisis than an economic one, in a way.”

With the layoffs averted and the publisher continuing operations, Menu would seem the person faced with the toughest personal challenges. Gauthey, a long-time friend, colleague, and once even publisher of Menu’s, recognizes this. “What you have to know is that all of us—even Lewis—really love Menu," he says. "For real. But we can’t accept everything from him. And he has his dark side and it’s very sad to see him going down into depression. He lost the chance he had for a more peaceful life, a more creative life. We don’t know what’s going to happen now, but I’m sure the story is not completely over.”

Menu indeed seems very troubled by what has happened, but—although he considers the “story” in different terms—he musters a certain optimism. “You know, [some] months ago, I wasn’t able to make this decision [to leave], because it was twenty years of my life," he says. "But when it became really insane I figured, OK, there’s no other solution—you have to do this. And I was really Zen about it. It was the only good solution to make. In the end I’m happy to quit, because I think the story is finished.”

And in the meantime, there seems to be a real will at L’Association now to put things back on track. Ruppert certainly does not want to give the crisis more play than it deserves and does not perceive its fallout as a problem in the long term. “This is a new beginning. It’s going to be great again.”