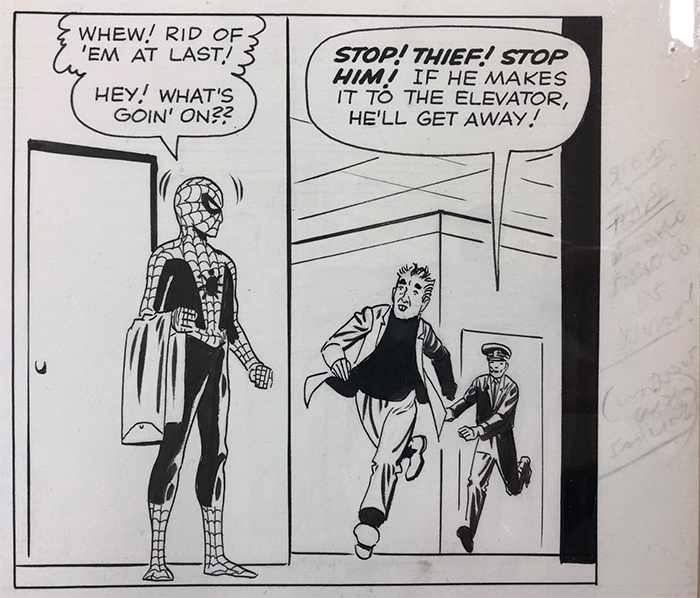

The pages look like they were drawn yesterday.

The ink is dark, the pages are crisp and you can still read the phantoms of Stan Lee’s erased pencil notes to artist Steve Ditko (“Steve, remove spider—change position of hand.”). You can also see, very clearly, when Ditko ignores Lee’s edits in Spider-Man’s origin story.

Today, the original pages from Amazing Fantasy #15 look—in short—amazing. I’d originally written about the anonymous donation of the pages to the Library of Congress in 2008, interviewing both Ditko and Lee (more on this in a moment) for the Chicago Tribune. But last summer was the only time that I’d been able to see the pages in person.

For fans of superhero comics, a visit to the Prints and Photographs division of the Library of Congress to see the Amazing Fantasy pages might be the closest thing there is to a religious pilgrimage for fans of original art. (Other contenders include the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University in Columbus. Admittedly, those institutions may appeal more to comic strip aficionados.)

My visit also allowed me to reconnect with Sara W. Duke, a curator of Popular and Applied Graphic Art at the library. In the 12 years that Amazing Fantasy #15 has been in the collection, hundreds of scholars, artists, writers and fans have come to pull secrets from Ditko and Lee’s alchemy of ink, paper and glue. Most visitors want a selfie, or to have their pictures taken with Amazing Fantasy’s pages. (Interestingly, there’s only one other item more popular when it comes to visitor selfies: a photo of Christian minister and faith healer William Branham, 1909-1965.)

The Prints and Photographs division of the Library of Congress is a particularly rarified air for the pages to live. Among its 16 million objects are the Depression-era photographs of Dorothea Lange, as well as Stanley Kubrick’s photos from when he was a photographer for LOOK magazine. The division also has a small but growing comic book art collection, including pages related to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Anyone age 16 or older with a government-issued ID can come look at the pages, but to see rare items like Amazing Fantasy #15, it’s best to call ahead and schedule an appointment.

But what, I asked Duke, can the original production art tell us about the origins of our friendly neighborhood Spider-Man?

“In this case, you had two headstrong creators who both said [Spider-Man] was their idea—you have direct evidence of that collaborative nature of that production,” Duke says.

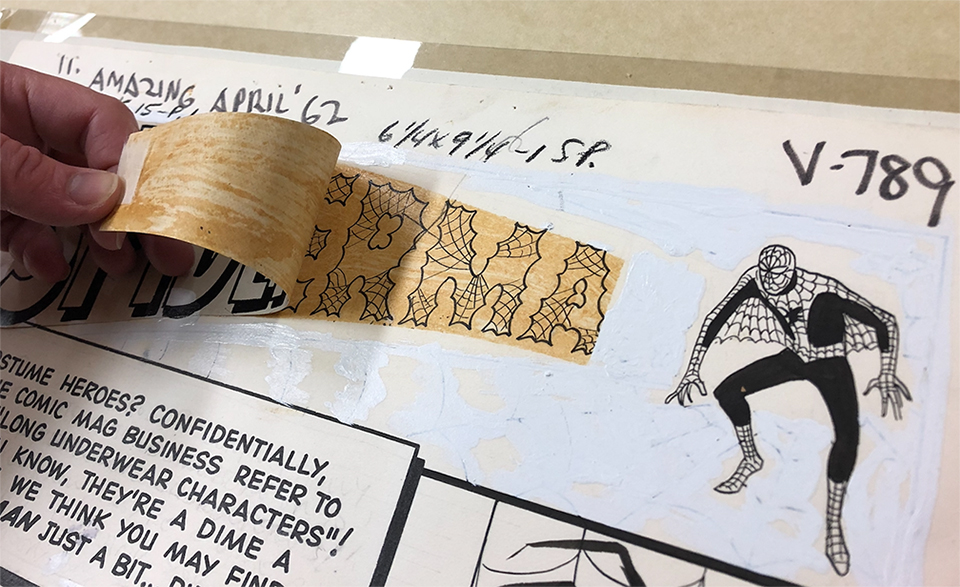

For me, seeing the art in person brought so much back to the surface, including the name “Spider-Man.” All throughout the story, the character is referred to as Spiderman, no hyphen. Looking at the title page, it’s awash in Wite-out and last-minute corrections. One of them was to paste a new logo—“Spider-Man!”—over a webbed logo design without the hyphen.

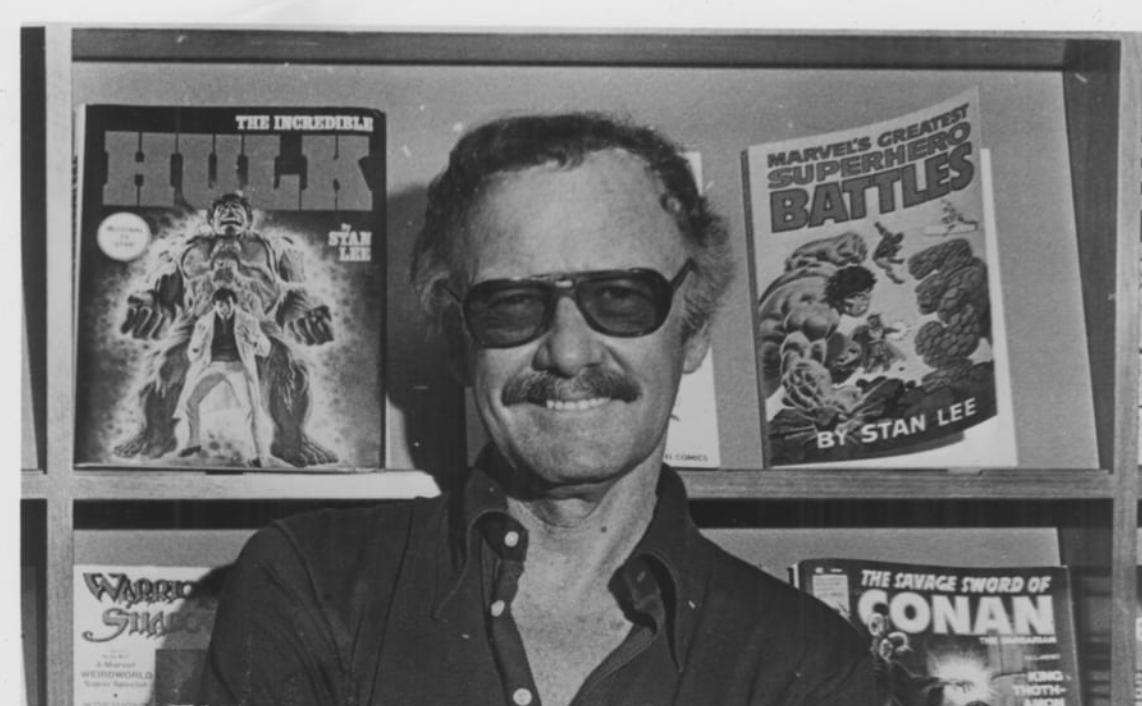

When I asked about the change in 2008, Lee explained, “It’s such a simple thing. I saw it lettered, and it looked a little bit like ‘Superman,’ and I didn’t want one to be confused with the other.”

Plus, he said, the webbed font wasn’t working for him. “I just thought [the original design] was too gingerbready, too busy,” said Lee, then 85.

Lee continued: “I wish I had my old scripts...but who ever thought to save those things? I think it's really great that comic book artwork is now considered important enough to be in the Library of Congress.”

When I called Ditko, then 80, he was much less talkative. Our exchange would also be recorded in Sean Howe’s book Marvel Comics: The Untold Story as one of Ditko’s last public statements to the press.

“I couldn’t care less,” Ditko told me.

It was in character for a creator who felt that Marvel had stolen his and other creators’ artwork. Famously, Ditko wrote a 28-page essay on the topic, “The Sore Spot Cause and Crusade,” published in 1993.

“In the thieves market how anyone came to possess [original art], has no meaning, makes no sense,” Ditko wrote.

After the story I wrote ran in the Chicago Tribune, I sent physical copies of the story to both Lee and Ditko, each of whom wrote back.

Ditko, sent a handwritten note saying thanks for the copies and “for the two pages of comic strips to review” (the arts section at the Chicago Tribune contained our daily comics). He also declined further comment, citing his valued privacy.

Lee emailed: “Well done. I’d hate to be a journalist whose job hinged on getting an interview with the estimable Mr. D; although he may be on to something. He seems to get even more publicity by shunning it.”

Ditko’s aversion to giving interviews and his devotion to Ayn Rand’s Objectivism made him even more of an enigma. Adding to his mystique: although he was offered the Amazing Fantasy pages before they were donated to the library, Ditko declined to take them.

In industry and fan circles, and among scholars, piecing together who the anonymous donor might be has become a bit a parlor game.

Only Duke knows the name of the donor. “I’m going to go to my grave and I’m not going to divulge it,” she says.

Duke will say, however, that there are no future donations planned from the source, adding, “I have never talked to the donor again.”

To Duke, the name of the donor is beside the point, a distraction.

“Isn’t it great that it ended up in an archive, rather than some wealthy person’s basement, where they don’t take it out of the box? Now, anybody can come and enjoy it,” Duke says. “That, to me, is the epitome of generosity.”

But, I offer, for many fans and scholars, finding the source of the pages could correct an historical injustice. It also might lead to the discovery of more lost artwork, including the pages not included in Irene Vartanoff’s inventory of original art in Marvel’s warehouse, which revealed a ton of missing artwork—including all of Fantastic Four #1 and the cover of Amazing Fantasy #15 (pencilled by Jack Kirby, inked by Ditko).

As for the missing cover, Duke says, “I think some researchers know [where it is], but nobody has told me. I have an inkling that the cover exists, but no one has ever confirmed or denied it.”

But, for Duke, the most interesting insights come from the pages themselves. Despite Lee’s and Ditko’s assertions, Spider-Man’s origin story was not a “throwaway story in a throwaway issue.”

“It obviously meant something to both of them because of the volume of inscriptions,” Duke says.

By contrast, out of 24 pages, there are a total of two notes in the three other Lee / Ditko stories in the issue, namely, “The Bell-Ringer,” “Man in the Mummy Case,” and “There Are Martians Among Us.”

There’s still more to learn, Duke says. “Every time I see that art, I see new things. It’s never dull for me to bring it out. It now belongs to everybody. This is America’s library.”

And Duke is looking to add more comic book art to the Library of Congress. Right now, the modest collection includes work by creators such as Will Eisner and Robert Crumb, as well as gems like a 1968 Hulk splash by Marie Severin and a 1971 Captain America story illustrated by Sal Buscema.

The collection is full of gaps, Duke says.

“We’re seeking representative art of major characters, major themes. It need not be Superman if it deals with racism or sexuality or political issues of the day,” Dukes says. “We love, as an institution, to look at how attitudes towards marginalized groups and social norms changes over time. Being able to represent that in art is fantastic, because it really helps people understand the history of the country. We’re documenting, through a mainstream medium, how attitudes change over time.”

For more information about the Library of Congress’ comic book art collection, how to visit or donate to it, go to: https://www.loc.gov/rr/askalib/

Robert K. Elder is a journalist and the author of 12 books, including the forthcoming Hemingway in Comics from Kent State University Press.