We asked a handful of writers to engage in a dialogue about Craig Thompson's Habibi. So, Charles Hatfield, Hayley Campbell, Chris Mautner, Tom Hart, Katie Haegele, and Joe McCulloch bravely waded in and corresponded with each other for a few weeks. The results show the range of reactions to this much-discussed book.

All images 2011 Craig Thompson unless otherwise noted

Charles Hatfield:

A veritable pearl diver, that Craig Thompson. He tends to plunge deep into a project and disappear, lost to sight, swallowed by his own undertaking for an agonizingly long spell—until, at last, just when you think he may have drowned in his ambition, he resurfaces with something glittering in hand. Consider that he’s spent the greater part of the past dozen years working on two books: the autobiographical Blankets (2003), the origins of which predate 1999, and which, we remember, earned Eisner, Harvey, and Ignatz Awards and a lot of love; and the new Habibi, released serendipitously on the fateful decennial of 9/11, but which he started long, long ago, in 2003, when Blankets had just hit. He was deeply into Habibi by the time I interviewed him more than six years ago.

Since then Habibi has been no secret. On the contrary, it’s been teased and telegraphed. For a long time, Thompson’s blog provided a running diary of the book’s creation, with mouthwatering roughs and plenty on process. Readers of that blog know that for the past year Habibi has been a nearly completed story slowly working its way into final, brick-like form. To say that the book has been keenly anticipated would be a pitiful understatement.

Shall I say for starters that, as bricks go, Habibi is gorgeous? That’s easy enough, but I think more than gorgeousness matters here. Reading Habibi was, for me, an exhausting, transporting, mood-altering experience—a bit troubling too. I just put the book down a couple of hours ago, and it’s still hanging over me like a bright, dazzling, yet frankly bemusing cloud.

Habibi is ambitious, certainly—staggeringly so. At its heart, obviously, is a sincere and adamant desire, a fevered ache. Thompson wants to give us something not only transporting but important: Habibi wants badly to bridge West and East, Christian and Muslim, the erotic and the implicitly political, the gutsy and the rightfully sensitive—in sum, religious, liberationist, ecological, and artistic agendas, timed and primed for our era. Tall order. Oddly enough, the book tries to do all this by way of an epic Oriental tale, a fanciful, 1001 Nights-inspired romance in an exotic, Easternized world.

Uh-oh. The usual ideological caveats about that genre apply here. Thompson, though, waxes allegorical, turning the Oriental fantasy into both an environmental alarm—parts of the book feel post-Hurricane Katrina, and anxiety over global warming is omnipresent—and a rebuke to Islamophobia. Some of the commentary isn’t even allegorical, but direct: among the horrors invoked here are conflicts over water rights, environmental racism, pollution, trafficking in human slaves, and, throughout, the threat of rape and sexual degradation. Habibi has a hell of a lot rattling around in it.

What possesses Thompson to build books like this? My guess is that he lures himself into projects like Habibi without taking full account of their likely scope and implications, or the depth and length of the dive they’ll require. On the face of it, Habibi is the love story of Dodola and Zam, escaped slaves who make a life together but then are forcibly parted, each to suffer transformations and losses before their final, emotionally fraught reunion. So very much else, though, comes to depend on that story: not only evocations of desire but also examinations of sexual shame, gender, motherhood, race, ecological catastrophe, writing, storytelling itself, and Thompson’s own concerted encounter with Islam and Islamic culture, including Quranic tales and teachings, the commonalities of Muslim and Christian scripture, the lore of Arab mathematics and numerology, and the art of Arabic calligraphy. The story is full-to-bursting with history, legend, intellectual schemata, and esoteric teachings—and Thompson has put all those elements to work in the book’s very design, conferring a unity and cohesion that are remarkable and deeply pleasurable. Yet it’s hard for me to imagine Thompson planning on all these things from the get-go; my sense is that Habibi, like Blankets before it, confirms the idea that writing is a process of discovery—organic, messy, and recursive, outward-turning but then inward-looping, additive, unpredictable, and demanding. He’s done a good job of hiding this by designing the book up the hilt, but Habibi is a wild sprawl.

Talking to Thompson about Blankets years ago, I gathered that, though he’d started with one express intention—to write a story of first love—he ended up tricking himself into engaging, sideways, a more difficult and demanding subject, the subject that, for me, gives Blankets its heft and integrity: his rejection of the Christian fundamentalism that defined his upbringing. To the extent that Blankets works, I think it works as a religious text. With hindsight, I don’t think it works entirely, because its two coming-of-age trajectories, that of first love and that of spiritual struggle, are uneasily intertwined, enough so that the attempts to resolve them together result in some mawkish and bewildering passages. Still, I credit Thompson with exploring far enough, and bravely enough, to go past a facile original conception toward something that truly got under his skin and bugged him. Habibi too has this quality of searching out something essential and tender to the touch—and, like Blankets, biting off a hell of a lot and creating a comic that is way too big for elegance.

When I spoke to Thompson, oh so long ago, I came away sensing that he was fascinated by three things: the virtuosity and prolificacy of his favorite European cartoonists, which he referred to as a kind of artistic “virility”; the organic quality of the lively brush line—stock in trade of his European favorites—which he referred to as “calligraphic”; and, very obviously, the beauty and grace of the female form, or at least an ideal of the female form, an interest that crowded his sketchbooks and that extends from Raina in Blankets to, now, Dodola in Habibi. All these fascinations are on view, are even conflated, in Habibi. Take as Exhibit A page 405, in which Zam at last sights the long-lost Dodola and, in his eyes, her body becomes a white silhouette filled with Arabic calligraphy, including long, swirling strokes that define her breasts and belly. That’s a fairly good synecdoche of what Thompson’s up to here, or at least what fascinated him enough to propel him through the project—though, as if to counterbalance the sensuality, the book also stresses, heavily and even alarmingly, sexual shame. Huh?

When I spoke to Thompson, oh so long ago, I came away sensing that he was fascinated by three things: the virtuosity and prolificacy of his favorite European cartoonists, which he referred to as a kind of artistic “virility”; the organic quality of the lively brush line—stock in trade of his European favorites—which he referred to as “calligraphic”; and, very obviously, the beauty and grace of the female form, or at least an ideal of the female form, an interest that crowded his sketchbooks and that extends from Raina in Blankets to, now, Dodola in Habibi. All these fascinations are on view, are even conflated, in Habibi. Take as Exhibit A page 405, in which Zam at last sights the long-lost Dodola and, in his eyes, her body becomes a white silhouette filled with Arabic calligraphy, including long, swirling strokes that define her breasts and belly. That’s a fairly good synecdoche of what Thompson’s up to here, or at least what fascinated him enough to propel him through the project—though, as if to counterbalance the sensuality, the book also stresses, heavily and even alarmingly, sexual shame. Huh?

I’ll close my first salvo by observing that Thompson seems influenced overmuch by Richard Francis Burton’s rendition of the Nights, specifically by Burton’s satyromania: his obsessive vision of the Nights, and more broadly the whole so-called Orient, as a distillation of an exotic and untrammeled eroticism (in contrast to the straitened, subliminated, or subterranean eroticism of 19th-century England). Thompson was reading Burton’s Nights years ago, I know, and Habibi’s plot owes something to the tropes of disguise and Oriental drag that were keystones of Burton’s reputation. In any case, he cranks the Burton-esque, Orientalist evocation of sensuality way, way up, drawing persistently on harem stereotypes, even the cliché of the concubine crawling up her master’s bed (page 241)—a canard that scholarship has debunked.

Historically, we know that harems were not palaces of sin but complex spaces in which women, or at least some women, though sequestered, may have enjoyed relative autonomy, status, and sociability. The harem—in essence, the women’s section of a Muslim household—was an enclave in which women could, to a degree, wield authority and shape their surroundings. In other words, it was a domestic and social space far from the stereotypical image of the seraglio as carnal playground. Furthermore, harems were not as isolated from the surrounding culture, or as irrelevant to it, as the stereotype insists. (I’m no expert in this area, but I’ve found particularly helpful Leslie Pierce’s The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire [Oxford, 1993], Reina Lewis’s Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel, and the Ottoman Harem [Rutgers, 2004], and Harem Histories: Envisioning Places and Living Spaces, edited by Marilyn Booth [Duke, 2010].) Habibi’s harem world, though, is that old, rutting male fantasy of the isolated pleasure palace ruled simply by the pasha’s sexual whims.

On some level I suspect Thompson knows this stuff to be fanciful and ahistorical. As if to admit it, he has his lecherous sultan character (for this is definitely an imperial harem) concede, “What I’m interested in is the fantasy” (198). But, still, there’s something disturbing about the way the book’s not-quite-licit enjoyment of erotic imagery is ambivalently paired with a guilty reflex. The book is full of harem baths, languid odalisques, and so on, which are cool except when you realize that Thompson wants both to luxuriate in these images of caged sexuality but also comment moralistically on the fetishistic pleasure they give. The result is a double-bind yoking pleasure to horror, a linking that haunts and frankly overwhelms the book. Dodola is its victim.

Now, Thompson must have known from the get-go that he was playing with fire, and the book is certainly self-aware. Perhaps we should thank him for being self-ware to the point that his depiction of sex is often conflicted and troublesome—but arguably there’s still an element of pandering in the florid erotic imagery, and, by using the exoticized East to license this tendency, Habibi participates in a pretty hoary tradition.

That the novel is flooded with genuine warmth and feeling, and has high personal stakes for Thompson, gives only a shaky warrant to its rapturous Orientalism—though I can for sure imagine teaching this in the next iteration of my Arabian Nights course, just to see what kind of fires it sparks. Maybe if I pair it with Edward Said?

Tom Hart:

Two people asked me to read Habibi because they were pretty sure they were appalled by it. One had read it, one had glanced at it. Finally I got a copy and made my way through it over three or four nights, expecting to be appalled. Of course, I have the same reservations that are common about Blankets: it’s virtuosic but gives nothing to the reader. Every thing to understand about the book is on the page. There’s nothing an adult reader can bring to it that Craig hasn’t already delineated...

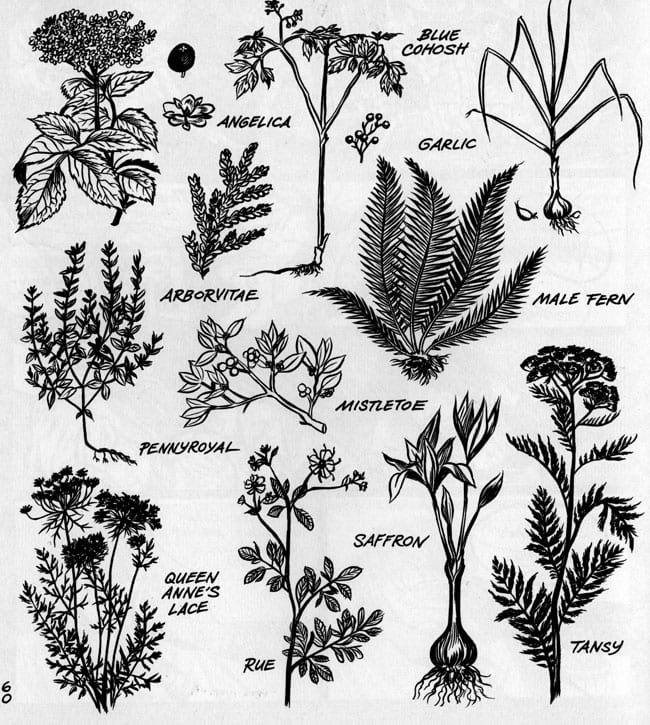

So, a mere 150 pages into Habibi, I found myself similarly a little annoyed at Craig’s grandstanding and too-obvious storytelling decisions—the panel when Dodola’s first desert rapist offers a basket of ripe fruit straight from his genitalia being one. Another annoying part was Craig’s virtuosic drawing-list of abortifacient herbs. “Yes, we all know you know how to draw herbs,” I thought. I stand by this as an unimportant page.

But eventually the story gripped me, and the intertwining of fable (religious tale, whatever) and the fable-ized main plot began to grab me. Something else grabbed me. He was telling the story of longing for a beloved. Many mystical poets play this card: they sing about the beloved but they are pining for God. Knowing what I know about Craig (mostly from the autobiographical Blankets), I began to be moved by this author’s story about a search for the beloved. I believe Craig to be someone who has lost faith, lost his connection to God, and this book, these pages and these stories, are very clearly, page after page, an attempt to call that faith back. When he grandstands as I said before, he is in danger of fraying that connection, but when he is in the story, when he is searching the Koranic fables, which I assume up until a few years ago he knew nothing about, I sense an author on a quest. This moves me. And the slow draping of the story with the modern accouterments seemed to parallel the religious fervor of this book. The story is a loss of Eden, and moving from a timeless Eden to to a Godless-Today makes perfect sense.

A great many of you will probably offer that his forays into Orientalism were way off the mark, and diverting himself from this search. I’m not sure how I feel about that yet, though I know he did his homework, and maybe just for fun: a lot of the more Orientalist images were cribbed (gleefully I think) from Ingres, and other famous artists of that period (sorry, I can’t remember them all—David, also? Delacroix?).

Likewise the humor in the story might be odd. I liked the little dwarf and most of the palace silliness, but could never place the head slave’s “Black Power” talk very well into my pleasure with the book. All that said, I admit that the main story of the two lovers ultimately grabbed me, but I like to be manipulated a bit if it’s done well and I surely will admit to certain prejudices: I want stories of triumph these days. I’ve been depressed too long.

There are a couple manipulations I applaud as a storyteller. Primarily when Dodola “turns water into gold.” You believe this passage to be a triumph while Craig changes chapters and you watch Zam go through his lowest point of losing his genitalia, etc. Had we known the outcome of Dodola’s shenanigans, the book at this point would have been overly pessimistic, very tragic, and probably just as manipulative, but I was happy not to feel nothing but misery in this section, believing that our heroine had triumphed. This is simple but smart macro-storytelling and I’m just saying that I personally liked the story being told that way.

There are a couple manipulations I applaud as a storyteller. Primarily when Dodola “turns water into gold.” You believe this passage to be a triumph while Craig changes chapters and you watch Zam go through his lowest point of losing his genitalia, etc. Had we known the outcome of Dodola’s shenanigans, the book at this point would have been overly pessimistic, very tragic, and probably just as manipulative, but I was happy not to feel nothing but misery in this section, believing that our heroine had triumphed. This is simple but smart macro-storytelling and I’m just saying that I personally liked the story being told that way.

Obviously, there are dozens of micro-storytelling decisions on every page and most of them are quite amazing. Craig plays with false light constantly (maybe too much in places), he decorates, makes fluid compositional choices, etc.

I’ll stop here and let others chime in, but, first, in reply to Charles’ opening, particularly about Thompson’s knowing use of fantasy: It should be pointed out that Craig is also playing fast and loose with the characters/places of this book. Namely, there are at least three vastly distinct Islamic peoples as main characters in this book: the Ottoman sultan and his palace, the desert Arabs, and the Indian sub-continent Muslims, who are the Hijra/Eunuchs he is depicting. It may be that he is exploring other Islamic areas as well, maybe Malaysia, Indonesia, etc., but I haven’t seen that yet. (On second thought, I’m taking an uneducated guess that the water and canal villages come from research into those cultures...?)

Katie Haegele:

I finished reading the book last night and I’ve got some thoughts to share. I’ll talk about my problems with the book first.

Going into this book I expected to be annoyed by its Orientalism, as some of you have called it (aptly—this book feels pretty 19th-century. Think it’s meant to, or is Thompson just revealing his own prejudice?). Actually READING the book I found much more egregious race issues that distracted me from caring about the story. For one, the “black” characters Zam and Hyacinth often look downright inhuman. To me this is very noticeable and disgusting. Do others see it? Also, Thompson has cast Hyacinth as some kind of lovable hood who talks in Black American vernacular, which is stupid on its own in a Hollywood-stereotype kind of way, and also inappropriate in this context.

Going into this book I expected to be annoyed by its Orientalism, as some of you have called it (aptly—this book feels pretty 19th-century. Think it’s meant to, or is Thompson just revealing his own prejudice?). Actually READING the book I found much more egregious race issues that distracted me from caring about the story. For one, the “black” characters Zam and Hyacinth often look downright inhuman. To me this is very noticeable and disgusting. Do others see it? Also, Thompson has cast Hyacinth as some kind of lovable hood who talks in Black American vernacular, which is stupid on its own in a Hollywood-stereotype kind of way, and also inappropriate in this context.

Thompson’s cornball humor is very odd and out of place. One of the worst moments was the racially insensitive joke made during a scene in the slave market: “No. This is not the variety of BLACK I am looking for.” Pointing to men standing in a line, the slave trader says, “But we have several hues: charcoal, cinnamon, shiny prune, chestnut,” and the final man says, “Actually, I’m closer to walnut.” Terrible. How could this joke be appropriate here, especially when the book has so little humor throughout it?

I noticed the wrongly-placed hijra too, and found it confusing, though by the book’s end, when I understood that there was an intentional blending of east and west, ancient and modern, it seemed less problematic. It’s obvious that Thompson did a lot of, erm, homework in writing this book, so this can’t just have been some careless mistake.

As for the sex—yes, it’s problematic, fetishistic of Dodola’s suffering and also of her ethnicity. I mean, that woman’s naked body, Jesus, I’ve seen it more times now than I’ve seen my own. But the truth is, it’s not uncommon for the treatment of women’s bodies in comics to be off-base in some way, distracting or downright hurtful. Poor Craig Thompson might have some especially complicated self-loathing stuff going on, I don’t know, but he’s not exactly in the minority in seeming preoccupied with his female characters’ sexuality. (As an almost-aside that I can’t resist mentioning: for all of his pervy attention to reproductive detail, he slips up in making Dodola’s slave-attendant Nadidah her wet nurse without ever showing us Nadidah either pregnant or working as a wet nurse before this. Which would be a problem because, well, that’s how lactation works.) A big YES to Charles’ observation that Thompson has attempted to moralize on the atrocities committed against Dodola but also is clearly rolling around in it himself, seeming to include her debasement among her list of attractive attributes. Again this is not uncommon, in comics or anyplace else—depictions of exploitation that are themselves exploitative.

That said, I actually really liked the sexual aspect of Zam’s story, when all was said and done—the way he, in denying his desire for Dodola, came nearly full-circle to BECOME her. The castration story initially seemed far-fetched and steeped in self-loathing in a very Christian way, but ultimately it was an interesting idea, I think. And the mystical sex scene toward the end, when Dodola teaches Zam what sex really is, was surprisingly moving and really lovely.

I can’t find it in myself to take issue with the lavish detailing in the drawings, even the pieces deemed show-offy by some. (I glanced at, but did not properly read, Michel Faber’s review in the Guardian and I appreciate that he addressed this “odd prejudice” in the comics world. Can we talk about it? I’d like to hear others’ thoughts. Since I’m not a visual artist myself it’s hard for me to touch down on what might annoy others about it, though maybe I can relate it to a certain kind of muscle-flexing in literary writing, an Martin Amis-style virtuosity that I can’t STAND. But as long as the story keeps moving forward, the odd portrait or botanical drawing doesn’t really stand in the way, does it? Discuss!) In any case I admire the visual detail, especially when it seems appropriate to the content, when the design (and size) of the book puts one to mind so obviously of a holy book. The image of the wooden ship marooned in the desert was especially poignant and lovely to me, the way at first glance the whorls of sand look like ocean waves until we realize that this boat isn’t going anywhere. Very nicely done.

At first, as the ancient/mythic gradually began to melt away into some polluted modern time, I felt vaguely confused and annoyed at what seemed like sanctimonious environmentalism, or something. But as it went on I enjoyed the new world I found myself in, and found it much more honest and warm than the exoticized Middle East of Thompson’s imagination.

Probably my favorite element in the book is the inventiveness with language, script, and naming: the snake that starts out as an Alif/Aleph and becomes other letters and words as it moves through the sand; the healing words that Dodola drinks. On this subject Thompson seemed quite sincerely personally engaged.

Also, I was impressed by the masterful way this book wrapped so many stories around each other—folklore, Koranic/Hebrew Scriptures/Christian Bible stories, and Thompson’s own stories. Some of this was a real education for me. But I wanted to feel touched, inspired, challenged, something more passionate and difficult; impressed isn’t good enough. It seems to me that there are ways of reconciling religion and faith, and reading this book I’m not convinced that an elaborate intellectual engagement with a religion that’s not your own is one of them.

Hayley Campbell:

Humour-wise, I’m going to disagree entirely with Katie here. I think there’s loads of humour in the book—some of it “cornball,” some of it a lot less obvious—all deployed very carefully at moments of unbearable tension as a way of letting the air out, releasing the pressure of the relentless grim doings in the main narrative. I liked the walnut joke (and do not think it’s racist, and I think that by denouncing this as being so, we’re trivialising stuff that really is racist), and I liked the two snails boarding Noah’s arc—“Do we count? We’re hermaphroditic,” then “I’ll play bottom.” It was an absurd and brilliant anomaly on an otherwise heartbreaking trajectory. The farting dwarf! And the fisherman in his squalid river of shit! “Why, you’re covered head to toe in feces!” he proclaims, with a beaming cartoon face.

In fact, I think my favourite part of the whole work is the stuff with the fisherman: his hut, his motley collection of hobos, his Tom & Jerry fish skeleton trophies. It felt like some Will Eisner book I’d never read before. Eisner is everywhere in this chapter: he’s there in the way the clothes fall, he’s there in the characters’ expressions. I was talking about the book to an envious Eddie Campbell (who is currently sitting forlornly by a mailbox in Australia waiting for a copy from Amazon) who told me he’d said all this long before I did, in The Comics Journal no less, in a 2004 review of Carnet de Voyage. He recently resurrected it on his blog:

Thompson’s Blankets was an interesting success from many angles, my favorite being that here was one of the bright young crowd merrily adapting a bunch of Eisnerian approaches into his own very individual style. Eisner’s kind of storytelling has tended to be seen in more than one decade as old-fashioned, only for a later crowd to come along and find it useful all over again. So once again we see a young artist picking up on the emotionally wrought figures, the expansive brush style, the centering of the image, letting a bit of random chiaroscuro account for the corners.

Bah, that guy says everything first.

As for the obvious storytelling techniques, I’ll partially agree with Tom, here. As a reviewer I’m regularly called upon to try and uncover the artist’s original idea or the deeper meaning in something they’re struggling to get across, or are maybe even deliberately being vague about for whatever infuriating reason. Thompson doesn’t make the reader do this at all—everything is already there and we can add nothing to it. But despite not being invited to participate, I can’t remember the last time I read a comic in such rapt silence without dicking about on Twitter between chapters. Maybe by feeding everything to us, the author’s got us on a tighter leash.

No one could spend so long submerged in a world like this without a deep and obsessive love for the stories and every detail they unearth. So forgive Thompson for the herbs, and the extended lessons on magic squares (though these do admittedly form the structure for the entire book, so you’d do well to know all about them). I actually really like it when writers go off on some tangent in a madly enthusiastic way. Should I ever need to, Herman Melville has furnished me with a detailed explanation of how to peel a sperm whale like an orange, and Nicholson Baker has given me the entire history of the rise and largely unnoticed fall of the paper drinking straw in a multiple-page footnote in The Mezzanine. The great David Foster Wallace’s work is roughly 90 percent tangential to the crux of his story.

Thinking about it some more, I think I place Habibi in the same place in my head as Moby Dick, in that Moby Dick is not really a book about a whale. It’s about everything there is. I just finished listening to Inkstuds’ very good podcast with Thompson — link here — and they sort of touch on what I was trying to say about footnotes and tangents, etc. Thompson was saying how much he’d been enjoying D&Q’s recent output of alternative manga titles (“gekiga”) because of their intentional wandering. “I love those moments in comics when you’re allowed to either visually or narratively wander off for a moment… Plot doesn’t interest me that much. When I’m reading a book and suddenly I feel sucked into a plot—a Point A to Point B to Point C—I get bored. I get that sort of existential boredom. I want to have more of a sense of no plot…. I think that’s what separates literature from a pop form of writing, which is about plot.”

Anyway. Probably Dan will say I sound too “fannish” but I can stand here and take it. I am. I think it’s a masterpiece. What a fucking book.

And as a little aside—anyone else notice it hit the New Release shelf in the same week as Frank Miller’s totally mental Holy Terror? Quite a double feature. Life and death, love and hate, side by side on the rack.

Joe McCulloch:

I’m personally hoping Xerxes is Miller’s full-length response to Habibi. If you think you’ve seen images of Arabic barbarism now, just wait till Frank the Tank rolls through!

Hayley:

Arf.

Joe:

Actually though—and speaking of authorial personae—I think there’s also a more fundamental separation at work between these two long-brewing fables. Miller, for all his superheroic accoutrement, is essentially working in a self-referential, I’d say nearly confessional mode; it isn’t for nothing that when Not Catwoman ventures into the underground space beneath the sinister mosque, Miller suddenly abandons his otherwise non-stop exotica-as-Othering practice to cross the parameter’s upper strata with what appears to be the Spartan helmets from 300 arranged in a double helix pattern. “Some say it was built by a race of madmen,” we’re told of the chamber’s exceedingly non-Orientalist decoration, nonetheless familiar as the frenzied subterrain of Frank Miller himself, an artist who’s happily soaked in the terrorist potential of Batman on earlier occasions and, in the end—as in, on the very final page of Holy Terror—pulls back the curtain to suggestively contextualize the entire preceding propaganda as the dream/memory of a tangential character: a non-superhero and an exceedingly troubled man, his personal life in ruins, trembling on his bed alone, perhaps involuntarily filtering the media sensations he’s absorbed in the '00s through an iconography built up over longer years.

A friend suggested this denouement operates in the same manner as those of Congress of the Animals and Love and Rockets: New Stories #4, as presenting a potential “ending” to the artist’s body of work; I’d at least agree Holy Terror pops livelier in the idiom of personal revelation than through the processes of mainline action comics, though adding this sort of despairing self-pity to Miller’s usually half-snarling/half-snickering indulgence—something I’ve often liked—makes the book uniquely noxious even beyond its political gameplay.

In contrast, Habibi—while obviously chock-full of Thompson’s personality—struck me as a more distanced look at narrative super-structures. The name Alan Moore began springing to mind as soon as the diagrammatic table of contents was explained on-page in Chapter One as a “river map”: both a summary of numbers—the nine save for zero that combine to form the basis of other numbers in Arabic numeration—as well as a fecund series of letters, the “four corners” of which serve as heavenly protection to the supplicant while the construct as a whole stands as a mystically-charged symbol of sacrifice, its zones inevitably adding up to the same sum, the end of trial. Fittingly, the image of the river map recurs throughout the book as a talisman of faith protruding through earthly suffering, just as the idea of the “river” is conjoined on page one with the properties of ink, and thereby drawing, and thereby language, and thereby comics, and ultimately this comic, as the word “Habibi” forms a pictogram of a river from the communion of—*gasp* *choke*—the very letters representing the first and last chapters of the book itself. WHAT A TWIST.

It’s a metaphor that endures throughout the book—nine chapters for nine numbers following the nothingness of zero, mapping the trial facing the book’s two lead characters as sure as that first drop of divine ink recurs just pages later as a virginal bloodstain, marking the first exploitation of the saga’s heroine and—in cruel parallel to Thompson’s own earlier metaphor—anticipating a blood river from the slit throat of the man who taught the girl to read and write: the man who raped her at age nine. Violence and aesthetics, as sure as blood and ink are indistinguishable in a black-and-white comic. As such, human boundaries are literally demarcated by the book’s contours; if you listen to what Seth tells you (as I do in all of life’s situations) and dispose of that fucking paper band on the back cover, you’ll notice that the image of the lead characters as children on the front cover—creeping around to the spine to capture them at the book’s midpoint—recurs on the back as a depiction of them at the book’s conclusion. If Thompson is grasping for the divine, he is nonetheless studied in the structure of myths, fables, books—chapters that sort of congeal into modular thematic inquiries.

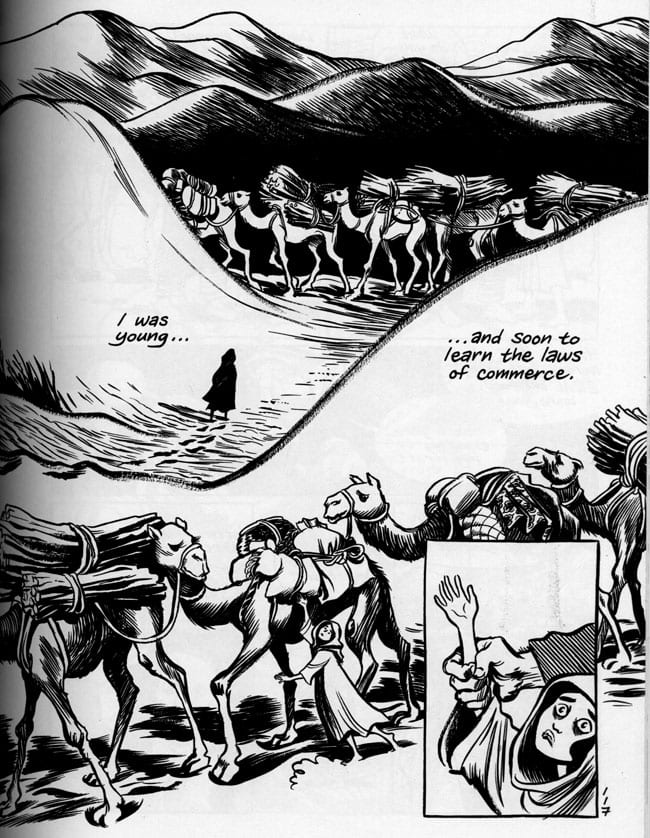

For example, chapter three (“Raping Eden”) is marked on the river map by the character for “labor” though it is specifically concerned with transaction, as announced in its opening lines: “I was young... and soon to learn the laws of commerce.” (I agree with Tom Hart that Thompson typically won’t leave anything implicit when there’s perfectly good space on the page.) “Labor” is Thompson’s term, not mine, and—as one might guess from its specific connotation alone—its chapter is heavily critical of unrestricted capitalism, with a particular emphasis on the commodification of Dodola’s body and thus her exploitation, in spite of the voluntary and “powerful” nature of her life of prostitution—obviously Thompson has been working on this book for years and years, yet cosmic arithmetic nonetheless posits Habibi in part as a delightfully harsh rebuke to a certain other thoroughly discussed and extremely Free Market-focused hardcover comic book of 2011 (er, this one, Joe?—CH) (I was thinking Owly & Wormy, Friends All Aflutter!, but that works too! —JM). The idea of bodily commodification then extends to Zam, who, in his rush to save Dodola from this situation, exploits the local village's need for clean water.

This is all interspersed with images of Edenic fable and local mystic custom, which when read at once form something of a problem—does Thompson suggest that taking from the Earth for sustenance is rape? Certainly one of the book’s master images makes its gala first appearance here: the dam, i.e. the blockade on the flow of the arch-image of the river, and, inevitably, an idolatrous substitute God indivisible from the economic apparatus benefiting and corrupting everyone on the contemporary end of the ancient/modern divide in which Habibi traffics. This, I think, is Thompson’s giveaway. He is not a convert to Islam, but his enthusiasms are such that he adopts the mindset of these stories, suggesting a bountiful Eden in the light of the divine as never-ending provision, while mankind separated from the divine is prone to ruination; the story of Job is duly related in commemoration of its characters’ powerlessness, save for their faith in divinity, again symbolized by the river map/amulet/storytelling/comics, which by this point has already become intermingled with images of both a serpent anticipating the flow of liquid (oh dear) and poor Zam’s doomed erect penis (oh, huh), which will itself be from inhibited from concerns for starvation and misplaced shame.

Many of these images also recur in later chapters, and truthfully I began wondering how much control Thompson had over his own creative flow. I enjoyed one of the subtler iconographic touches in chapter three: the triangles representing the four elements, which recur both in the retelling of Job—an upward triangle for fire (trial) and a downward triangle for water (succor)—and the chapter’s apocalyptic rape scene with the separate points of the triangles representing the disconnect of Dodola (now drowning) and her rapist (burning through his climax). This setup is reversed in chapter seven—which, if we view the book as a now screamingly, inescapably Alan Moore-like symmetry, is the counterpart of Chapter Three on the nine-chapter scale, though not every chapter is so responsive to its counterpart—where two triangles with pointing tips are drawn on the River Map to symbolize the womb and the serpent, and between them the precarious balance of human relations premised on reproductive necessity, replaced by chapter’s end with a revisiting of the non-pointing triangles as icons of Heaven and Earth, now intermingling into one another to form a star, which spreads out to form the pattern of Love—which eagle-eyed readers will note is exactly the varied pattern behind each chapter heading—and foreshadows the final chapter’s notion of stars and crosses forming the “breath” of the River Map’s squares, as metaphoric of the breathing of proper, affectionate lovers who don’t really need one another to be in perfect factory-fresh condition psychologically or below-the-belt to function an a rightly Beloved manner. Which is really what counts, eh?

I’m enough of a brat, however, to keep track of all these charged images and wonder why Rape and Trial and Fire (volcanic upturned triangle, remember!) in Chapter Three has suddenly become Heaven itself in Chapter Seven. I am likewise inclined to follow Thompson’s life-as-river-as-snake-as-penis-as-alif chain of symbolic custody to the conclusion that this “tree trunk from which all letters extend as branches” (Ch. 8, p. 603) is perhaps an unwitting fortification of that classic paternalistic conception of the male father as creator of all things, fitting enough for a work this eager to adopt the viewpoint of its subject of study but played so hard across so many, er, cascading icons that it enshrines this concept with verily cosmic force in a manner at odds with both the shouted “I” of the entirely subjective, narrated, near picture-free alif chapter (again, Ch. 8), and indeed the ostensible gender equanimity of the book’s text. I mean, as Katie points out, Zam has practically become Dodola by the book’s midpoint, in that he’s dressing as a woman and nearly pressed into prostitution himself, but deviations from the gendered norm are always contextualized as either mutilating social constructs or misguided reactions to earthly suffering, a la the “false god” of Bahuchara Mata. I found myself wondering how an apparently secular, monied metropolis like Wanatolia didn’t have any alternative cultural enclave in it, or even how the presumably multi-religious makeup of its people might affect its societal operation, even as I realized that acknowledging such positives of urban existence would distract from the purity of Thompson’s metaphor of consumption as an aspect of separation from the divine, and secularism as consumption itself.

I know it isn’t the project of Habibi to address these things; it’s a love story augmented by a studious exploration of Islamic writings, with the love poised to humanize a caricatured culture and the study often meant to sap their Other-ness through emphasizing parallel traditions. The latter effect was stronger than the former for me; I never particularly clicked with the characters as human beings (which isn’t an instant dismissal for me, though it will be for many), while I was pretty pumped over some of the cumulative images of image-as-recognition, like the hand of Fatimah rearranging itself into the opening words of the Qur’an, or the final sex scene revealing itself as the very molecular formula of the book. But to invoke so much in an often nebulous, de-specified manner is to invite the charges that Thompson has produced little more than a gaudy bauble, oblivious to its malign implications and pathetic in its pretension. Candidly, when I see Charles describe Thompson’s writing process as discovery, tricking himself into taking on bigger topics, I wonder if such delving hasn’t weakened the very bloodflow of the work: its sloshing river of associations.