Over the past eighteen years, fragments of the Rusty Brown story appeared in the New Yorker and Acme Novelty Library volumes, which makes reading Rusty Brown like getting reacquainted with old friends we haven’t seen in ages. In fact, it’s not one story but three interlinked stories—we are brought into the worlds of eight-year-old Rusty Brown, aspiring superhero, and his preoccupied father, Woody Brown; Jordan Lint, a spoiled, self-involved child who grows up to be a domineering patriarch; and Joanna Cole, dedicated elementary school teacher, and a black woman working in a conspicuously white, and often unwelcoming, environment. Pieces of these stories have accumulated over the years, and the dedicated reader will find references connecting distant characters and works. In a sense, Ware’s narrative has the ambition of a novel cycle like Balzac’s Human Comedy, but rather than witnessing the moral and power struggles of 19th century France, we are transported into lives of midwestern characters of the American 1960s and 70s. As remote as this comparison may initially appear, both projects are meditations on the role of social status, power, money, love, and parentage in determining a character’s fate. Each character’s perspective is cast into relief against another’s, producing a kind of shock of recognition in the attentive reader.

In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera develops his theory of the “polyphonic novel” to describe the pacing of The Joke (1967), his bitter satire of ideological extremism and the failure of humor. Because sections are narrated through the voices of different characters, the readers are able to fully grasp how characters deceive, betray, and misunderstand each other. A similar dynamic is at play in Rusty Brown when the contrasting perspectives different characters clash, sometimes on the same page, as is the case with Woody Brown and Alison White in the first section. Alison is nervous for her first day of school, and tries to comfort her little brother; when seen from Woody’s perspective, however, Alison bears an uncanny resemblance to Woody’s first lover (as we eventually discover). The rhythm of each character’s perspective creates a form of musical counterpoint in combination with the other narrative strands. This kind of text cannot be truly appreciated at one go and invites slow reading and re-reading. David Mazzucchelli, author of Asterios Polyp, articulates this narrative structure through the character Kalvin Kohoutek, who explains his theory of composition:

Simultaneity—the awareness of so much happening at once—is now the most salient aspect of contemporary life. In a cacophony of information, each listener, by focusing on certain tones and phrases, can become an active participant in creating a unique polyphonic experience.

Rusty Brown is such a polyphonic novel—graphic novel, that is. Taking this proposition as a possible starting point, I invited a group of scholars who contributed chapters to The Comics of Chris Ware ten years ago to offer different possible interpretations and perspectives on Rusty Brown. Warning: the discussion that follows does contain some spoilers for those who have not read the book. --Martha Kuhlman

The Contributors

Dave Ball is series editor for Critical Approaches to Comics Artists and working on a monograph about the intersections of comics and modernist art and literary history.

Georgiana Banita is co-editor with Lee Konstantinou of the forthcoming Artful Breakdowns: The Comics of Art Spiegelman and currently completing a monograph on wordless comics. She is a Research Professor at the University of Bamberg, Germany.

Joanna Davis-McElligatt is an Assistant Professor of Black Literary Studies at the University of North Texas. She is currently co-editing, with Jim Coby, a collection entitled _BOOM! #*@&! Splat: Comics and Violence_.

Shawn Gilmore is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and writes on comics, prose, film, and the like, teaching the same, and is the editor of The Vault of Culture.

Martha Kuhlman is Professor of Comparative Literature in the Department of English and Cultural Studies at Bryant University. With José Alaniz, she co-edited Comics of the New Europe, forthcoming from Leuven University Press this spring.

Peter Sattler, Professor of American Literature at Lakeland University, spends much of his time thinking about early American comic strips and other arts.

Daniel Worden is the author of Neoliberal Nonfictions: The Documentary Aesthetic from Joan Didion to Jay-Z and the editor of the forthcoming The Comics of R. Crumb: Underground in the Art Museum. He is an Associate Professor in the School of Individualized Study and the Department of English at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Georgiana Banita: What draws me to Chris Ware is the way he maps lived time onto a lifeless comics page, seemingly without difficulty or compromise. It’s a staple problematic of Ware Studies and, to be fair, not even an exclusive trademark of the Warean universe. McGuire’s time-travelling Here is attuned to the same fluid frequency. Kevin Huizenga’s recent “The River at Night” reproduces a Buddhist mandala to suggest the interconnectedness of experience. And yet Rusty Brown marches to a different beat than these books, or even than Jimmy Corrigan or Building Stories. The way the novel codifies the dissection of the moment into an overarching statement on the nature of time is openly indebted to some of the artists Ware admires most, from Kriegstein to Faulkner. Rusty Brown may in fact be Ware’s most overt engagement with modernist time, which the astronomy buff takes one step further by venturing into the astrophysics of space-time.

My reading is anchored in the Mars segment that, for lack of better words, I can only describe as “Mark Beyer in space.” The story and realization are frightful, just bone-chillingly bleak. But Mars helps Ware dramatize the conflict between Einstein’s spatial, objective, mathematical time and Henri Bergson’s subjective, mind-dependent duration. By building its story around individual timelines rather than a single reference frame, Rusty Brown continues the modernist literary tradition that Bergson influenced so greatly by pushing it to discard measurable, scientific time in favor of a more tangled form. In a medium like comics, one that is so dependent on a succession of separate moments—quilted or braided together, but distinct instances nonetheless—Ware’s elastic temporality might hold an even greater subversive potential.

For the Rusty of “The Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars,” who passes his time reading Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, time is relative only to his own consciousness. The unchanging landscape with the rocket at one end and Rusty’s small house at the other implies that time does not exist outside his perception; once the colony comes to a standstill, so does time. The confined architecture of the strip rests on several well-threaded themes like weightlessness and the circular aesthetics of space travel, iterated in pretty much everything from the rocket design to doors and helmets. On the final page, we see Rusty desperately trying to break up the indivisible time bubble he is trapped in by catching a glimpse of the Earth through his fingers “just for a second.” Meanwhile Woody Brown tries the same thing when he looks up from the page to gaze at intersecting cracks in the wall; yet they remain stubbornly fixed from panel to panel, like the hands of a clock that has stopped marking time in discrete units. The same gelatinous intervals surface in Jordan Lint’s life story through the recurring effects of faces mirrored in window panes, blurred vision, and pointless temporal cues (“so,” “but,” “then,” “after,” etc.). For Joanne Cole in the final section, the experience of time as lived consciousness has political implications, too, as archival material of Nebraska’s lynching history intersects with the casual racism she endures in a predominantly white school.

Most of all, I’m obsessed with the out-of-time, wordless panels that fill entire pages, panels that to me appear modeled on Precisionist paintings by the likes of Edward Hopper or Charles Sheeler. They interrupt the narrative so unobtrusively, though, that while reading, I’m not shifting location from an indoor to an outdoor space as much as zooming in on a picture on the wall inside the same scaleless room where all the particles of the book are confusedly collecting. Ware assembled this prismatic novel from non-concurrent segments that dropped at different times over the last decade. To me, this confirms that even if he had written something entirely new and ostensibly self-contained, it could only make sense in relation to what came before and might follow (see the “Intermission” cue on the last page). Any work, in other words, is mysteriously caught in the indeterminate continuity of its creation.

Daniel Worden: There is much in Rusty Brown that harkens back to Ware’s other works. Perhaps most notably, in the volume’s first half, we encounter stories of two frustrated artists, working on the margins of high and low art forms. W.K. Brown’s “Seeing-Eye Dogs of Mars” is published in the pulp sci-fi magazine Nebulous, and the high-school art teacher Mr. Ware’s Lichtenstein-esque paintings of superheroes are intended to produce “an intuitive transcendence of culture and corpus.” Both struggle with the realities of middle age and their mundane cycles of work as educators, while holding on to their ambitions like talismans, dim flickers of their wounded senses of superiority. Indeed, both Brown’s pulp sci-fi story and Mr. Ware’s derivative paintings are preoccupied with failed heroism, whether it’s Brown’s Martian settler-turned-psychopath or Mr. Ware’s self image as a tortured artist hoping to escape the genre content he nonetheless cannot eschew.

These kinds of figures are familiar territory for Ware, whose characters often yearn for a kind of artistic or social recognition not forthcoming. On a formal level, Ware’s own understanding of the comics medium involves an inherent conflict between high and low art status, captured in self-ironizing remarks such as the Rusty Brown dust jacket’s definition of “comic strip” as a “colorfully playful, disposable and active-yet-seemingly-passive reading experience.” This reflexive anxiety about the legitimacy of comics as an art form is, I think, the major theme of many cartoonists of the RAW moment and afterwards, from Art Spiegelman’s synthesis of modernist art techniques with genre material, to artists like Ware and Daniel Clowes whose long-form narratives feature cyphers for the comics artist, doing the work of making art yet acutely aware of the cultural biases that surround them. Today, this kind of anxiety about comics might seem outdated, as the medium seems to have fully graduated into mainstream art and literary culture through the success of Ware and others, as well as the ubiquity of works by artists like Raina Telgemeier in grade school libraries.

Yet, I think Rusty Brown’s representation of art-making as a melancholic process, overwritten by self-doubt and the looming inevitably that one’s work will not connect with others, means something more, too. The historical sweep of Rusty Brown helps to clarify what the book is about, as it is fundamentally rooted in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In Ware’s dreary Nebraskan setting, we see the emergence of what Phil A. Neel has described as America’s “hinterland” in his 2018 book of the same name. Neel’s “hinterland” is not a remote location, but instead the alienating and isolating geography of suburban development, constituted by stagnant wages and increasing debt, a foreclosure of the upward mobility so prized by the architects of finance capitalism yet so unavailable to us today (and, in retrospect, to many of those who supported ideas like “trickle-down economics” as a solution to economic and political crises of the 1960s and 1970s). As Neel writes, “the thing about poverty in these suburbs is that it doesn’t look like poverty, just as class doesn’t look like class” (126). In Rusty Brown, it is visibly apparent that the teachers who are at the core of the narrative are not comfortably middle class, but are instead struggling in both a threadbare, deteriorating environment, and a culture with no sense of community or collective belonging.

For most of Rusty Brown, connection seems impossible, as characters exist in their own fantasy worlds, and even their own temporalities, as Georgiana Banita points out above. But, I think there is a glimmer at the end of Rusty Brown of something beyond the dirge of the depleted Midwest. The character in Rusty Brown closest to the stereotypical “boomer” who has plundered the planet and exploited the young and dispossessed, all to fuel his sense of relevance and consumer-based lifestyle, Jason Lint, dies alone haunted by his own self involvement, his last words “i am.” The book transitions from that point to Joanne Cole’s chapter, where a hint of human connection and collective belonging emerges, a glimmer of bonds forged amidst the desolation wrought by finance capitalism, neoliberalism, and structural racism. The more I think about it, the more I believe that Rusty Brown is about class in America today and how we got to our current moment, from technocratic planning and rock-n-roll individualism to crumbling infrastructures and exploitative rents. For me, the heartbreaking beauty of Rusty Brown is that its characters, like many of us today, can’t recognize each other in solidarity against the structures that limit them.

Banita: Daniel’s comments on Rusty Brown’s neoliberal universe got me thinking about the disintegrated families whose lives intersect in the book. Alienation of all sorts is festering inside them, and not necessarily of the cloying kind bred over time by routine and long-held frustrations. Far from forging and fostering emotional bonds, the family is perhaps the traumatic center of the novel. And it works so well to frustrate these people’s desire for attachment precisely because, in theory at least, that’s what a family is supposed to do: connect, protect, and bring comfort to its members. Family has been a part of comics’ DNA from the start, both in the sense that cartoonists love drawing children—from the Katzenjammer Kids to Schulz’s Charlie Brown and Ware’s own Jimmy Corrigan—and that comics themselves have had to outgrow their juvenile beginnings. With underground comics, Spiegelman’s Maus, and Bechdel’s Fun Home, among many others, the image of the wholesome family unit from Golden Age Sunday comic strips gave way to a bleaker picture of family entanglements going far beyond familiar comics tropes of childhood frolicking, sibling rivalry, and questionable parenthood. Rusty Brown is set against the tail end of the Nixon era, and the endpaper references to the administrations that overlapped with the writing of the book’s various sections (Clinton, G.W. Bush, Obama, and Trump) suggest that such a seemingly arbitrary historical marker may indeed hold some significance. Most superhero and underground comics are usually too busy doodling muscular abs, buxom female bodies, or pornographic sex to bother with the question of conception, but Ware gives us a rare opportunity to watch the consequences of intercourse under an administration that transformed family planning services.

It’s a nice touch from Ware to have Rusty Brown come up with the fantasy of “super-hearing” as a special power he must use “to protect the unprotected” while overhearing his parents argue about his lacking sense of responsibility about shoveling the driveway. Throughout the book, the inner machinations of child-parent relationships seem grounded in the primal trauma of becoming a family. Rusty’s father has no inkling of his son’s reveries as he stares through the window at an absent-minded Rusty no longer shoveling but standing eerily still in the garage door. “This house, this woman, this child … What are they?” When Woody fantasizes about amorous encounters at the Holiday Inn, it’s as if he was trying to undo the sexual act that sealed his fate as a husband and a father. Lots of opinions are voiced about pregnancy and childbirth in the novel, sometimes overtly (Alice: “Okay mum we’re leaving! I’ll be home when I’m pregnant!”) to suggest that sex as a rite of passage helps set the “stiff gypsum of maturity” into which the protagonists are trapped; mostly though in the puzzled tone of a man somewhat perplexed by the mysteries of conception. After meeting his future wife, Sandy, and fathering a child with her, a young Woody wonders how his first lover, a moodier and more promiscuous woman he had fallen head over heels in love with, managed to avoid pregnancy.

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, white American women gained control over their reproductive decisions while black women were left to endure systematic efforts to limit their reproductive freedom, amounting to what Dorothy Roberts in 1997 described as “the degradation of Black motherhood” (Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty). Rusty Brown ends with the emollient scene of the reunion between Joanna Cole and her long-lost daughter, now a neonatal nurse, that instead of obscuring only draws attention to the circumstances of their separation. Between 1960 and 1970, during the so-called baby scoop era, many women were forced to relinquish children conceived out of wedlock, but it was especially common for black mothers to be coerced into giving up their newborns. I wish Ware had gone into more detail about Joanne’s inner life as a mother beyond implying that the baby was forcibly removed from her while she was sedated, so she never even knew whether it was a boy or a girl. Rusty Brown furnishes granular detail about its white characters’ sexuality and parental pathologies. Joanne is humanely, almost reverently rendered, yet from this perspective she seems woefully underwritten.

Joanna Davis-McElligatt: I appreciate Georgiana’s convincing read of Joanne’s forcible loss of her daughter, Janice Woods, during the Baby Scoop Era. As Joanne tearfully explains when she is at last reunited, she “tried … everything” to find her child, “but they put me to sleep,” never bothering to tell her “was it a boy … was it a girl …” Joanne’s aimless exploration of newspaper archives on microfilm might be said to function as substitute for the fruitless impossibility of her pursuit of her child. In fact, in the end we learn that it is Janice, at Amy Corrigan’s urging, an editor’s note clarifies, who ultimately locates Joanne. Ware’s invocation of Amy from Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, a black adopted woman who never learns that she shares ancestors with her white Irish adopted family, forces us to continue the pain that attends histories and pasts which are fundamentally, irrevocably lost. Joanne is at last united with her daughter—but they remain strangers to one another.

As Saidiya Hartman explained in Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (2007), the slave trade permanently constructed the enslaved African and her descendants as strangers. For many vaulted across the Atlantic, the stranger-making process of slavery left the enslaved with no ability to reclaim their pasts; torn from languages, home lands, customs, fathers, brothers, and daughters, to be black and in diaspora is to lose all trace of one’s mother. Joanne, Janice, and Amy’s enslaved African ancestors, and they themselves, are “the perpetual outcast, the coerced migrant, the foreigner, the shamefaced child in the lineage.” As we see in Joanne and her mother’s relocation from the South to white upper Midwest, in Joanne’s inability to recover even the memory of the loss of her child, and echoed in her engagements with Louise, the only black student at the Catholic school where she works, to be a stranger is to exist perpetually and marginally in a new world and to never be fully known, even to one’s self. In many ways, the Joanna/Joanne section is an exploration of what it means to be made a stranger, which is in Hartman’s terms what it means to be black in a white supremacist system.

As a black Midwesterner raised in Illinois and Iowa myself, I was struck by how clearly Ware investigates the ways quotidian racism renders Joanne a stranger to herself, her family, her colleagues, her students, and her life in Omaha. Over and over again, we see white people spit on her, refuse to eat food she prepared, undermine her credentials, solicit her for sex, ignore her, belittle her, and call her into question—a repeating pattern that is never disrupted, even at novel’s end. The pain of these scenes were, for me, somewhat buttressed by Joanne’s engagements with black Omahans; in her interactions with them there is an implicit acknowledgment of an underlying discriminatory structure. Yet because Joanne must spend her life precariously straddling and forcibly integrating deepy segregated spaces, there are no places where she can become entirely incorporated. Indeed, eventually Joanne’s own mother ceases to recognize her, confusing her with her estranged sister, Jeanine. It is to Ware’s credit that he avoids speculating about what Joanne’s emotional responses to racism might be. However, by laying bare the many layers of macro- and microaggressions that define Joanne’s daily life, readers are asked to confront the ways human experiences and relationships are malformed and shaped in what Hartman calls “the afterlife of slavery,” or the lingering effects of the slavery on every aspect of our society.

I was struck the fact that both Jimmy Corrigan and Rusty Brown explore how the afterlife of slavery is so often registering of the failure of generations to know themselves as family. I look forward to seeing how Ware continues to grapple with the interpersonal and intellectual consequences on the body politic of these unknowable and inaccessible histories.

Shawn Gilmore: To be honest, I’ve found Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown (2019) more challenging to grapple with than I had anticipated. The book is not as unified as Jimmy Corrigan (2000) and less overtly experimental than Building Stories (2012), but instead manages to bring together elements of each while mining the emotional and psychological development of a small set of characters whose lives briefly intersect in a high school in Omaha, Nebraska in the 1970s. As Georgiana and Daniel note above, some of these portraits are both affecting and thought-provoking in terms of the themes and aesthetic possibilities they suggest, and much can be made by exploring each character’s arc, inner life, and presentation in the collection.

However, think it’s important to note the structure Ware employs here, with an “Introduction” occupying the first two-fifths or so of the book, followed by three relatively discrete character studies focusing (as pointed out above) on Rusty’s father, William (Woody) Brown, Jordan Lint, and Joanne Cole. As with Jimmy Corrigan and Building Stories before, most of that material had been serialized in Ware’s ACME Novelty Library, since 2005, particularly in issues #16, 17, 19, and 20, and appears here relatively unchanged, with only the last portion being mostly new to this volume. [Also, as with Jimmy Corrigan, earlier, one-off Rusty Brown stories that appeared in ACME #10, 11, and 15 do not appear in this compiled volume.] This allows Ware to begin with troubled child Rusty Brown, the school he attends, and the variety of players that intersect with his story (including art teacher Franklin Christenson Ware), before splintering the rest of the book into three formally-distinct character studies.

When I’ve written about Ware previously, I’ve focused on the disconnect between private experience and public history in Jimmy Corrigan and the mix of forms as a challenge to narrative progress in Building Stories. And I had read two of the four sections of Rusty Brown that had previously appeared in ACME, so perhaps I had expected more coherence across the book, which is limited to minor narrative intersections between some characters. Further, early reviews stressed Ware’s return to standard themes, calling him “The Bard of Sadtown” and asking “Does Chris Ware Still Hate Fun?” and I’m sure these conditioned my reading as well, leading to me expect tales of depressed, morose characters throughout.

That said, I find Rusty Brown more successful than I had first thought, at least when considered in the vein of something like Sherwood Anderson’s prose short story collection Winesburg, Ohio, published a hundred years earlier, in 1919. Subtitled “A Group of Tales of Ohio Small Town Life,” Winesburg is a masterful story cycle, presenting a series of loosely interrelated tales of desperate, isolated figures whose traumatic pasts and personal obsessions keep them from connecting with or understanding one another.

The collection opens with “The Book of the Grotesque,” in which an aging writer attempts to describe those around him:

[…] the interest in all this lies in the figures that went before the eyes of the writer. They were all grotesques. All of the men and women the writer had ever known had become grotesques. The grotesques were not all horrible. Some were amusing, some almost beautiful […] The old man had listed hundreds of the truths in his book. […] It was the truths that made the people grotesques. The old man had quite an elaborate theory concerning the matter. It was his notion that the moment one of the people took one of the truths to himself, called it his truth, and tried to live his life by it, he became a grotesque and the truth he embraced became a falsehood.

While Ware’s work often lacks a central thesis for the pitiful, estranged lives of his characters, I find this approach to thinking of his characters as beautiful “grotesques” helpful. Each character’s full story is withheld from others, their personal pain, joys, desires, and desperation isolated away. Here, Ware makes this isolation formal, with the stories of Woody Brown, Jordan Lint, and Joanna Cole masterfully drawn (though not, to my mind. without flaws).

As those above have highlighted Woody’s story, in particular—the one I found most affective—I want to add a note on what Ware is able to accomplish in these portraits (which I treat much more fully in a piece at The Vault of Culture). Much of Woody’s narrative deals with his youthful past, dwelling on a science-fiction story he had published as a young man, his first real lover, and his inability to fit in the world of corporate office work (like middle-age Jimmy Corrigan). These threads spool out over dozens of pages revealing he can no longer hold these parts together, landing on a cacophonous page, with some 176 panels surrounding a central reflection my dissipated middle-aged school teacher Woody: “Now, that time of my life all just little pieces of memories that speed by in a flash (or linger, if I want them to)… None of it makes any sense… I guess all roads lead to the present, though…” This, as much as anything, seems to sum up the potential of Ware’s approach in Rusty Brown.

Peter Sattler: Whose comic is this anyway?

This is the question I asked while reading Shawn’s meditation on the mosaic of Woody Brown’s life, filled with images that slide between first-person perspectives and third-person reconstructions, between blotted visual experiences (through tears, fantasies, and poor eyesight) and the narratives one makes of them after the fact.

And the same question applies to the words at the center of the page, where we find Brown silently plagiarizing and repurposing ideas from his own – or, rather, from “W.K. Brown”’s – youthful science fiction. Of course, this is entirely fitting: almost everything we have seen of Brown’s short story has come to us, not directly, but instead through the mind of the older man. To whom, then, do these words and images really belong? And whose perspectives are we seeing? Whose comic is this anyway?

I’ve asked these kinds of questions—questions about the experience of memory—in my own study of Chris Ware’s Building Stories, published in Martha and David’s 2010 collection. But the inquiries of that younger reader and critic never seem to resolve themselves into anything resembling a conclusion.

In fact, my old questions pose themselves anew about two-thirds of the way through Rusty Brown, when Jordan Lint, aged 61, begins to read about the time he violently snapped his own son’s collarbone. This is the moment, you’ll certainly recall, when Rusty Brown breaks.

Ware’s customary artwork suddenly disappears, replaced with what reads like a jam of sublimated comic influences: Philip Guston, Gary Panter, Mark Beyer, Ron Regé, Chris Forgues, Ben Jones—all in a raggedly expressionist monochrome, straight off the Risograph. Even the physical orientation of the novel shifts ninety degrees, its story and style turned sideways.

But again, whose comic is this? The answer is that these pages were created, essentially, by Jordan Lint himself. Gabriel Lint's memoir exists as text, visible on Jordan's computer screen. The comic, however, exists in Jordan's mind—or rather, in his experience of that text. It emerges somewhere in the space between the son’s memory and the father’s imagination. Gabriel Lint’s words are replaced by Jordan Lint’s DIY creation.

In this way, these pages simulate the primal scene of reading, at least as Ware envisions it. Words and comics seem to happen somewhere in the space between the page itself and the reader’s mental enactment of that page’s contents. The book translates itself into new images, filtered through memories, now externalized.

Jordan Lint’s “comic” seems to testify to the power and promise of that reading experience. In a moment of empathy, a father can suddenly see the feelings of his own wounded son, and thereby see himself (as he is seen by his victim). Jordan’s normal ways of looking, as well as Rusty Brown’s normal ways of storytelling, give way to something new and transformative.

The change, though, is short-lived. Ware’s style and Lint’s character both reassert themselves, almost immediately. Indeed, Jordan’s empathetic opportunity ends as we turn the page, into the year 2020, only to find that the father has sued his son for defamation.

Moreover, Jordan’s alt-comic memory—for all its apparent novelty—actually recycles much of its imagery from elsewhere in the chapter. The geometric abstraction of Gabriel’s face recalls Jordan’s own birth-image, the shrieking face and monstrous outstretched hands repurpose those of Jordan’s mother (and his wives), and the repeated images of a violent father reflect those we see in the Lint backyard of 1961.

Even the scene’s most visually gruesome effects arrive secondhand. Fists clutching a child’s neck are imported from the births of Zach and Levi, as well as from Jordan’s flashback during a recent medical exam. And the explosion of Gabriel’s pain reproduces the halo of Jordan’s own out-of-body experience in a car crash—or, alternately, of an orgasm.

Even the scene’s most visually gruesome effects arrive secondhand. Fists clutching a child’s neck are imported from the births of Zach and Levi, as well as from Jordan’s flashback during a recent medical exam. And the explosion of Gabriel’s pain reproduces the halo of Jordan’s own out-of-body experience in a car crash—or, alternately, of an orgasm.

In this way, the most un-Ware like pages in Rusty Brown speak to the themes of the novel as a whole. To a person, Ware’s characters seem chronically unable to imagine the lives of others. Extended dialogue is all but absent. Few of these protagonists talk with other people, except through walls and doors (Rusty and Woody Brown), off-panel spaces (Jordan Lint), conversational tics (Joanne Cole), and the incessant detour of your own thoughts (Mr. Ware).

Even the epiphany of Gabriel Lint’s pain cannot stanch the flow of auto-narrative and self-conception. In fact, when these pages first appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review, they were accompanied by Jordan’s own thoughts, running along the header: “Summer, 1995. / Or was it 1996? / It was 1996. Summer 1996.” (Adding insult to injury, these years in the “Lint” chapter show no hint of violence – only Jordan’s placid religiosity [1995] and a sad feeling that he doesn’t know how to talk to an upset six-year-old Gabe [1996].)

Everything is a remix, and your own self-image shines back from any attempt to see or speak beyond the screen or page in front of you. The novel is threaded with such motifs: reflections atop reflections, images reproduced through squinted eyes and broken lenses.

But the “Lint” chapter stands as an overture to the inarticulate monologue. You type a letter, and the keyboard sticks. You think about your new partner, wishing at the same time that she would “just shut up.” You pray, but those words turn to blood in your mouth. And even your clumsiest pantomimes of true love – how God, or perhaps your mother, “meant for me to meet you” — become an articulated hiccup of “me me me” and “ma ma ma.” (For more on this, see the back cover of Acme Novelty Library #20.)

Chris Ware has said that the comics page—at least for its artist—is a “paper mirror,” which allows a “horrible person” to stare back at you while you draw. Rusty Brown, by making comics part of the way we already think and read, insists that this mirror is unavoidable, especially when it poses as a pane or a panel.

So whose comic is this again? Ware has elsewhere hoped that Rusty Brown would capture the “sense of inevitable change and shift of memory as we unseeingly daily and hourly recall and anticipate our lives while life itself passes us by.” Seeing, unseeing, mis-seeing: that just about answer the question, for the book’s characters and its readers.

If Building Stories simulated a web of a novel that no one ever really wrote, Rusty Brown turns the project back on itself, exploring the interior life of a graphic novel—your own—that no one can ever truly read.

Worden: I think Georgiana and Joanna have clarified what makes Rusty Brown compelling and unique, especially in its final, new chapter focused on Joanne Cole. On the book’s dust jacket, Ware categorizes each section of Rusty Brown as a genre: Rusty’s opening section is “Comedy,” Woody’s section is “Western,” Jordan Lint’s is “Science Fiction,” and Joanne Cole’s is “Drama.” I wonder about this genre schema, and if the implication here is that the Joanne Cole section should be approached as being more realistic than the other sections of the book, because “drama” is not necessarily tethered to popular or formulaic genre forms--it seems like a more expansive category than, say, “Western.” Or, it could be that the genre category of “drama” means, for Ware, something more akin to melodrama, which would also explain the emotional punch of the book’s final section, as Joanne and her daughter meet each other for the first time. Either way, and as Shawn and Peter have pointed out, the book does seem to want to spin its characters out into multiple trajectories, temporalities, and genres -- extreme polyphony, to borrow Martha’s term from the introduction. I find Janice’s comforting words to Joanne poignant here, for thinking about Rusty Brown’s use of genre: “You did the right thing … then and now … but we’re not supposed to find each other … the system’s not set up that way.” Janice articulates a compelling framework for thinking about the book as a whole: each character in Rusty Brown is isolated in their own way, yet the realization that this isolation is, in part, by design makes some connections possible. The piling on of genres makes them visible as “systems” that obscure even as they shape narratives. In its cycling through genres and its dramatic conclusion, Ware’s book seems to be grappling with how to tell a story that can both focus on individual characters and do justice to the systematic brutalities that constitute so much of U.S. history.

Worden: I think Georgiana and Joanna have clarified what makes Rusty Brown compelling and unique, especially in its final, new chapter focused on Joanne Cole. On the book’s dust jacket, Ware categorizes each section of Rusty Brown as a genre: Rusty’s opening section is “Comedy,” Woody’s section is “Western,” Jordan Lint’s is “Science Fiction,” and Joanne Cole’s is “Drama.” I wonder about this genre schema, and if the implication here is that the Joanne Cole section should be approached as being more realistic than the other sections of the book, because “drama” is not necessarily tethered to popular or formulaic genre forms--it seems like a more expansive category than, say, “Western.” Or, it could be that the genre category of “drama” means, for Ware, something more akin to melodrama, which would also explain the emotional punch of the book’s final section, as Joanne and her daughter meet each other for the first time. Either way, and as Shawn and Peter have pointed out, the book does seem to want to spin its characters out into multiple trajectories, temporalities, and genres -- extreme polyphony, to borrow Martha’s term from the introduction. I find Janice’s comforting words to Joanne poignant here, for thinking about Rusty Brown’s use of genre: “You did the right thing … then and now … but we’re not supposed to find each other … the system’s not set up that way.” Janice articulates a compelling framework for thinking about the book as a whole: each character in Rusty Brown is isolated in their own way, yet the realization that this isolation is, in part, by design makes some connections possible. The piling on of genres makes them visible as “systems” that obscure even as they shape narratives. In its cycling through genres and its dramatic conclusion, Ware’s book seems to be grappling with how to tell a story that can both focus on individual characters and do justice to the systematic brutalities that constitute so much of U.S. history.

David M. Ball: When I first wrote about Chris Ware’s comics it was in 2010—two kids later; two states, three houses, and a job ago—a fact that seems both mundane and seismic in its implications. As a fledgling literary scholar and a rank amateur in the world of comics criticism, what drew me to Ware’s work then was his brash experimentalism, his sweeping gestures to the whole of US history, the sense that he had the entire medium at his command. It was Ware as the direct descendant of Melville, Joyce, and Faulkner. It was the Ware of reverse dust jackets revealing world-historical maps (Jimmy Corrigan) and serial covers stitched together in multiple editions to tell generational stories of loss (“Thanksgiving”/ACME Novelty Library #18.5). It was the conviction that Ware’s fiction was the most exciting thing I’d read in the twenty-first century.

In the ten years since the publication of Martha Kuhlman’s and my co-edited The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking, Ware has since released the collected Building Stories, the massive, retrospective Monograph, and most recently the first, 300+-page act of Rusty Brown, all narratives that were visible in part in the earlier work and all startling creations in their own right when seen in their totality. Ware the experimentalist is still very much in evidence, from Building Stories’ box of fourteen books, read in an order determined by the individual reader, to Jordan Lint’s chapter in Rusty Brown (first published as ACME Novelty Library #20), each year of his life told as a page reflecting his cognitive perception of the world at that moment, from object permanence to the paroxysms of dementia. I still find these narrative risks exhilarating and unexpected, richly rewarding as experiences of reading.

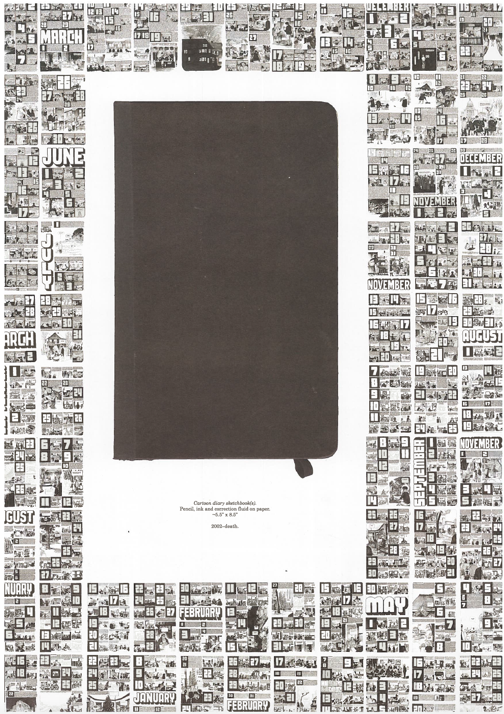

Yet it is Ware the humanist, the recorder of everyday time and its progression, who most moves me as a reader now and has helped me make sense of these past ten years. Steadily mining an interior Yoknapatawpha of suburban despond, a terrain of missed connections and human frailties, Ware’s work now reads to me as that of a diarist, an archivist of quotidian life. Not so much Pablo Picasso as On Kawara, painting dates steadily through the years, hand lettering himself and his characters into existence in a prodigious act of recording. Visible from his earliest fascinations with time in Quimby and Sparky’s vaudevillian pratfalls and Jimmy Corrigan’s diagrams, Ware’s work reads most clearly to me now as a diary of time itself. “[C]artoonists are odd, as artists go,” Ware wrote in Monograph, where his unpublished diary comics crowd the page in miniature: “we spend the majority of our lives sitting at a table staring down into a reflecting pool of paper on which we trace our surfacing memories, ambitions, and lies in the form of little doodles” (60). Those doodles still read to me like one of the most important contributions to contemporary literature not for the grandness of their ambition but for the reflections that shine in their stillness. That I needed my son’s junior gemologist magnifying glass to read many of the words in Rusty Brown seemed a particularly Wareian touch, both an exercise in close reading and an apt study in the passage of time (and the aging of my eyes).

Reflecting on my first two readings of Rusty Brown, I was drawn to the Joanne Cole section that concludes the first published act of the novel, perhaps in part because it holds much of the previously unpublished material in the volume. Cole is the long-suffering colleague of both Woody Brown and the metafictional “Mr. Ware” character. She is also the teacher of both Lint and the titular Rusty Brown, in a familiar if seemingly distant orbit in the solar system of Ware’s Omaha. She appears throughout the earlier sections but is easily displaced, a slice of her vest framing early morning tableaus of the teachers’ lounge, her censorious figure looming over Rusty in sudden flashes. Yet as her section opens in full, the pages expand. We see her withstand the concrete ceiling for Black women professionals, the casual if cutting racism of her charges and her colleagues alike, and most powerfully, the separation of Black families as old as the Atlantic slave trade. We might view her as a nod to representations of Black endurance across the depravations of US history in a line from the earliest representations of African American suffering, clear inheritor of a figure like Faulkner’s Dilsey Gibson in The Sound and the Fury.

Yet Joanne’s narrative refuses her the role of simple helpmeet to the novel’s white characters. Rusty and Jordan are just two of her more difficult charges; the novel expands instead on a reunion between Joanne and one of the few African American students at her parochial school, documenting the ways in which these women helped buoy one another in an at-times hostile environment. It shows her in all her complications, both in tears upon hearing a rare compliment from an otherwise unseen white coworker, and enraged at her sister and elderly mother for the undue burdens of care placed upon her as the older, (seemingly) childless sister. And when the novel reunites Joanne with her adult daughter, who we learn has been the subject of a tireless search that marks nearly every day of Joanne’s adult life, we resonate with the simultaneous relief and intense sadness that marks their reunion.

We are having a national conversation about who has the right to tell whose story, whether the identification possible in literature and art allows for meaningful and rich translation across identities and experiences. This amidst a moment in which the cruelest, crudest, and most backward looking voices seem to have crowded all else from the national stage. That Ware has given over much of his late work to telling the stories of women and people of color remains for this reader, with my own blinders very much in place, something still worth celebrating. Ware is keenly aware of the risks of voyeurism and minstrelsy in such an act; Joanne’s banjo is no accidental choice. Yet he chooses to document her story in exacting detail, drifting daringly across moments in her life. I’m drawn back again and again to a two-page spread that records a day in her life, her figure rotating around the demands of her daily routine.

The white actors in this drama now occupy the margins—Woody’s ashtray in the ninth panel, Chalky White (another of Ware’s hapless, bullied misfit-collectors) on his first day of school in the tenth panel—while Joanne commands the symmetrical stage, her meals and commute, and most poignantly her search for her daughter shaping the composition. There she is entering the school library in the eighth panel and bound to the microfilm reader in the seventeenth. She asks us, in the final panel, to look backward, to reread more closely, to fill in the gutters between these images. I’m hopeful her story will be extended in the volume, or volumes, of Rusty Brown to come. Stories of quiet dignity, maybe even redemption, feel like they’re in precious short supply these days.

The white actors in this drama now occupy the margins—Woody’s ashtray in the ninth panel, Chalky White (another of Ware’s hapless, bullied misfit-collectors) on his first day of school in the tenth panel—while Joanne commands the symmetrical stage, her meals and commute, and most poignantly her search for her daughter shaping the composition. There she is entering the school library in the eighth panel and bound to the microfilm reader in the seventeenth. She asks us, in the final panel, to look backward, to reread more closely, to fill in the gutters between these images. I’m hopeful her story will be extended in the volume, or volumes, of Rusty Brown to come. Stories of quiet dignity, maybe even redemption, feel like they’re in precious short supply these days.

I am eager to see where Ware, and we along with him, go from here.

Martha Kuhlman: As was the case ten years ago when we initially decided to assemble a series of essays on Chris Ware’s work, I am continually amazed by all of the various possible disciplinary angles one can pursue and find so much to say. American literature, Art history, the history of race relations, science fiction, quotidian experience, the representation of time, American popular culture, comics history––these are a few of the frameworks through which one can unpack and explore aspects of Rusty Brown.

There is something paradoxical, and yet hopeful, about the way in which all of these readings chart the emotional chasms that separate the characters from each other––but we, as readers, connect with the stories nonetheless. We are genuinely moved by Rusty Brown, which goes against a popular snarky reading of Ware that dismisses his work as too cold or cerebral. Over the past ten years, there has been a rising interest in whether literature can promote empathy in readers. Although it’s not possible to offer a definitive answer to this question, it’s worth noting that Suzanne Keen, the theorist at the forefront of this trend, sees special potential in the form of the graphic novel to evoke empathy given the visceral impact of the combination of word and image. At a time when our official American political narrative is triumphant, arrogant, and unapologetic, these smaller-scale narratives ask us to slow down, to be humble, to inhabit the lives of people possibly quite different from ourselves, and imagine how the world looks through their eyes. We look over the shoulder of Joanna Cole as she gazes at the white children playing in the schoolyard, or at Woody, as he recalls his lost sci-fi dreams; or at Jordon Lint, when he surveys the wreckage of his broken family, and think about what it would feel like to be in their position. In an interview with Belgian comics scholar Gert Meesters, Ware remarked, “If human beings have any superpower ...it's the ability to feel for, about and most especially through others. There is no more important skill we can learn [...]”