Part of a group who defected from Charlton to DC in the ’60s, comics writer Denny O’Neil, who had a background in journalism, is best known for expanding the superhero genre to include socially conscious themes that helped attract adult readers in the 1970s. Though he is probably best known for his work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, he also created the characters Ra’s al Ghul and Richard Dragon and edited the Batman books for DC for 15 years. For Marvel, he worked with Frank Miller on Daredevil and wrote for Iron Fist and Iron Man ...

..two characters that writer Matt Fraction has had a hand in revamping, probably most famously in Invincible Iron Man, a six-issue miniseries that was timed to coincide with the release of the 2008 film. He’s also worked on top-tier Marvel titles such as The Uncanny X-Men. In addition to his mainstream work, Fraction also writes Casanova, a critically acclaimed creator-owned Image title that features a metaphysical take on the spy genre.

Matt Fraction: I have this theory that they’ve put us together on the phone because we’re both from Missouri. I think that was how this came about. I think they had a list of people —

Denny O’Neil: Where in Missouri are you from?

MF: I am calling from Kansas City.

DO: Oh, OK. That’s probably about 300 miles east. One of the last major conventions I did while I was still gainfully employed by DC was in KC with Devin Grayson and Greg Rucka.

MF: Oh gosh, I was probably at that show, weirdly enough. So you were born in St. Louis —

DO: Well, Clayton — it was virtually St. Louis — it was one of those things where you can’t tell where St. Louis ends and Clayton begins.

MF: What was your childhood like? What were your folks like?

DO: Irish Catholic. Not a terrible childhood — nobody beat me — but the nun did lock me in the convent basement every night in eighth grade. It was not a great environment for someone with my limitations and someone with my proclivities and, dare I use the word, talent. The arts were not encouraged, even less so when I went to a Christian military high school — talk about bad casting! [Fraction laughs.]

MF: I actually had in my notes that you had gone to a military high school and that led to time in the Navy where you were on a ship involved in a blockade during the Cuban Missile Crisis?

DO: Yeah, that’s my little piece of history.

MF: What was that like?

DO: It was strange. I was in school — atomic, biological and chemical warfare school — in Rhode Island [Fraction laughs] about to stick a needle in my leg and inject myself with atropine because what we were told was: If you were exposed to nerve gas and can get atropine into your system within 30 seconds, you’ll probably be OK. So, that’s what they teach you — just jam it into your leg and squeeze. But I didn’t have to do that because a Marine came and said, “Everybody report to your ships. Don’t bother to pack; we’ll take care of that. Just go to your duty station immediately.” And we did and an hour or two later, we were heading for the Caribbean and then for about four days, we really didn’t know what was going on. We were on battle alert 24/7. We knew that our pilots were flying round the clock and they were taking thousands of photographs. I saw some of the photographs and they were of Russian ships with their holds. One of them was a photo of a Russian ship with its hold open and a woman in a bikini on the fantail, which was a little treat when you were at sea for a long time. When it was all over, we found out what we had been doing, when the crisis was past and we were heading back to the U.S. I edited a shipboard newspaper and I guess I saw AP stuff and wire-service stuff about then on what we had just gone through. I mean, I have — somewhere in this house — a medal, like all those who participated in that, and it’s an interesting comment on getting medals because we didn’t know what we were doing and that we were in harm’s way. I mean, what were we going to do, swim home? You had to do whatever combat duties they assigned you because you really didn’t have a choice.

MF: So, how old were you then?

DO: 21, 22, something like that.

MF: There’s a — I’m guessing here — but there’s a sort of a shift in the way that military culture was viewed at that point with the war resistance, and all that hadn’t started and there wasn’t such a thing as draft dodging or anything like that.

DO: Well, not much.

MF: And for somebody with an artistic background, I wanted to ask about the Catholic Workers Movement and how these two things were reconciling in your head.

DO: Well, I had run into some of the Catholic radicals while I was still in college and the Catholic Workers — I guess they’re still publishing — and it cost a penny a copy. I somehow got hold of some copies of that and I was sympathetic, but I thought, “These people are impractical and if we don’t stop the Communists in Southeast Asia, they’ll be camping on my mother’s front lawn,” the whole ridiculous thing that the whole country was buying. I was possibly the worst sailor in the history of the U.S. Navy [Fraction laughs] so that was another bad fit. I’ve worn three different uniforms in my life and none of them really fit. But I got out and fell in with the civil-rights and peace movement in St. Louis and suddenly, I began to have sources of information that weren’t Establishment. By the time I moved to New York, where a lot of my social life was Catholic Worker and I was married to a woman who had been raised on a Catholic Worker farm, I was completely convinced — as I remain — that the guys in the brown suits and the ties who claim to know what they’re doing, don’t. The years of the Bush administration were a great demonstration of that: “We don’t know how to fight a guerrilla war, so we’ll bomb because that’s what we know how to do. And never mind that we’re bombing the wrong country.”

MF: Right, right. And any civilians that might be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

DO: And making people like Dick Cheney rich, is how stock tripled in the course of the war. I mean, I’m astonished that the American people can be so obtuse. It was so obvious that he was unqualified and then, after the first term, that they were pursuing what was really a radical agenda. In this country, we tend to think of radical as left-wing, but it swings the other way just as far.

MF: Sure. I remember being particularly worked up and stunned at least with some people in my group in 2000 — the apathy — there’s always election apathy, but really in 2000 not voting really registered, somehow, as a valid decision. Not that I’ve ever been one to say, “I told you so,” but, man. When your vice president was the head of your committee to discover who should become your vice president and decided he was the guy… [laughter] from Jump Street, something was fishy.

DO: And it just got fishier and fishier.

MF: And then to be re-elected — I mean, granted, Kerry wasn’t necessarily a stellar candidate — it’s amazing to see what’s happening in Iran right now.

DO: Yeah, I was surprised that so many people of your generation didn’t realize that it was their asses that were gonna get shot off. Some of the war resisters for the Vietnam War didn’t want to get shot and they were pretty open about that.

MF: Yeah, I think that had there been a draft, it would have been different. I think like you said, that we’re so good at bombing things — it’s videogame warfare. I mean the guys in the troops — I mean, God bless ’em and keep ’em safe — I think there was the clear and present danger of a draft being removed from anyone’s living memory amongst my generation. It was abstract, in a lot of ways.

DO: Yeah, you’re absolutely right, Matt, you guys really didn’t need to worry about it. We had the lottery and we knew, barring wangling a deferment or some kind of physical problem, you were gonna go in and serve some kind of time somewhere.

MF: Yeah, my dad volunteered, just because he knew — sooner rather than later — and it was, I think, ’66, ’67 that he went and it hadn’t gotten necessarily as bad as it was going to get by the end of things. It was just what you did, you know? His number was gonna come up and he knew it and he figured he might as well get it over with.

DO: Well, I joined the Navy just because I thought that I would maybe travel more [Fraction laughs] and maybe get that out of it. I liked boats! [Laughter.] Was your father a military man?

MF: Retail — close! A very similar kind of orthodoxy in that we moved every couple of years.

THE DIRECT MARKET

Kristy Valenti: Between the two of you, you have spanned the rise and, arguably, the fall of the Direct Market. So, I was wondering, Matt, if you had some comment on that, or if you’d like to refute me?

MF: I think the Direct Market — I don’t understand the virtue of a sales program … platform … design? The sales mandate that thinks selling in fewer locations is wiser than selling in more locations. I moved around a lot as a kid and I moved to towns that didn’t have a Direct Market outlet, and it was infuriating. So, it was very rare that I lived in a place big enough to have a Direct Market store. So, I had to fight to keep up and I think that kept me in — I got stubborn and got into the fact that reading comic books meant you had to hunt for the ones you really wanted. Of course, nowadays, the Internet has made that entirely irrelevant, but in that mid- to late-’80s timeframe, it made it quite difficult. Even today, it’s one of those things where my family has trouble finding my work — they have to live somewhere that has a comic-book shop. I don’t know if I’m actually answering the question.

KV: It’s just fascinating to me how people come to comics and how they obtain comics because I do not have that Direct Market collector mentality either. I don’t feel as connected to the Direct Market as I could be and I feel like you, out of the three of us here, are the one who is.

MF: But I never was because I was never a diligent bag-and-boarder. The best thing I can say about the collector mentality is that it put a friend of mine through his first semester in college. He was able to gain a speculation bubble over a two-week period and bring in enough money to put himself through school when he couldn’t afford financial aid. For that — great — God bless the collectors because they kept my buddy in school. I was too busy hunting the damn things to want to put them away. It was never about finding a thing that was going to be worth money; I was very much driven by the narrative. I grew up in a culture where variant covers existed, but it was a little after my time that all that ridiculous stuff really came. I was into girls and drugs by the time the real collector mania stuff started.

In terms of the Direct Market growing and the newsstand market dying, I still remember comics on Monday at 7-Eleven — that was new-comics day.

DO: There are people who argue that comics as — I use this word advisedly — a mass-publication venue, would not have existed without ol’ Phil Seuling and his nutty Direct Market idea. That was at a time when magazines — very like the one we’re going through — were really dying. Things like The Saturday Evening Post that you thought were the Rock of Gibraltar, they would always exist, and suddenly they weren’t there anymore. The normal newsstands were not on the corner anymore.

I’m not comfortable with that collector mentality at all. You’ll be at a convention and somebody will say, “I have every Detective Comics published for the last 20 years!”

I’ll say, “That’s nice.”

“Well, what are the stories about these days?”

“I thought you said you had—”

“Oh, I don’t read them.”

I did not become a writer to write for Mylar bags.

MF: Exactly. One of my favorite editors is fond of saying that monthly comics is a train that leaves the station every 28 days. If you’re not on it, then somebody else will be. Just in terms of deadlines, it’s gotta go — the book’s gotta go out.

DEADLINES

DO: Is that a problem for you guys, the deadline thing?

MF: I love it. It keeps me honest, you know? I would nitpick endlessly if I didn’t have deadlines — and I’m sure there are people that do have problems — I thrive with that little bit of pressure. It helps me not be precious; I could noodle around forever would I not have people calling and asking, “Where’s the script?”

DO: You hear people like Julie Schwartz talking — well, you don’t hear him anymore — but it was evidently one of the things that hurt Bill Finger’s professional survival and it’s a problem that goes way back. I was at DC to do a talking-head thing a few months ago and I asked one of my editor friends, “What’s your biggest problem?” and he said, “Getting two consecutive issues out of a given team.” It was certainly the major problem I had as an editor, both at Marvel and DC. The guys who will go to work for television and scrupulously adhere to TV schedules to do a 60-page teleplay, but can’t do a 22-page comic in months.

MF: I think there’s a pay priority differential.

DO: Yeah, but it’s also a cultural thing and I’ve never heard anyone say anything that I agree with more than what you said just now: I like deadlines because they focus you. It has nothing to do with the quality of the work; there are writers who are fast and there are writers who aren’t.

MF: I’ve done a couple of writing seminars and what-have-you and one of the best — if I could go back in time and tell myself anything about it, it would be: Give yourself the gift of sucking. You kind of have to let yourself be lousy and just do better next time and believe that there will be a next time and get it done and move on to the next thing. Otherwise, I’d have paralysis by analysis.

DO: Did you major in English?

MF: No, I was an art and a film major. Close enough, we’d have been in the same cafeterias. I very much came from a production culture in my education where we had to produce work constantly. So, I need that little nervousness, that little shock of adrenaline just to keep things going.

DO: The worst thing about being an editor — one of the reasons I retired three years early — was you had to fire occasionally. That’s an awful experience on both sides of the desk. But I once took someone off a book and I pointed out that this person had missed a dozen deadlines in a row and the writer didn’t understand why I was upset about that, why that was a reason to switch writers. It’s something about the people who come up primarily through fan culture — it’s their hobby. The other thing is — Dick Giordano used to say, “We have to remember we’re not curing cancer.” We had to remember that what we do — storytelling — is very deep in the human psyche and very important to us, and may have something to do with our survival. But, any individual story — whether it’s written by Shakespeare or by the guy who does the funnies for the bubblegum — is not, at the end of the day, that important. It’s an interesting job, it’s a fascinating job, I can’t imagine anything that would have given me more satisfaction, and not everything I did was awful, but it was just writing another story in a world that’s full of stories.

MF: Yeah. This is interesting — one of the things I really wanted to ask was about the transition you made from writing to editorial. You still had your foot in both worlds, but what was that transition like? What was it like as a job — what was the corporate culture like at the time? Tell me about Denny O’Neil, Writer, becoming Denny O’Neil, Editor.

DO: Well, my life was very, very bumpy at the time. Going through a divorce, did a lot of drinking and carousing, and I was maybe past the worst of that but I realized that I had a kid who was starting high school and I needed more money. If I wrote any more, I might have been compromising — I had enough regard for what I did to want to do it as well as possible, given whatever limitations were in effect. So, I went to DC and said, “I really need a few more bucks,” and their answer was to offer me some more books to write. Well, I was writing a book for Scholastic Publications on the history of comics and that involved interviewing a lot of people, one of whom was Jim Shooter at Marvel. So, I went in to talk to Jim about this chapter I was writing and he offered me a job. It was an editing job, it was something I could do with the left side of my brain. I’d let DC make a counter-offer and they didn’t have anything like that open. Jenette Kahn hired me as an editor the first year she was there. That was during the worst of my bad life, bringing a thermos chock full of cheap brandy to work every day — not recommended, this is not the path to career advancement.

MF: Yeah, I was a gin man myself; also available cheap and readily.

DO: Yes, exactly. So that job only lasted a year, but when Jim made this offer, it just came at exactly the right time. I was looking for something to do to make a living that did not necessarily involve writing. It was interesting that, for about six months, I didn’t have to write and found that I missed it. The question you ask is, “Am I doing this just to put food on the table, or is it something deeper?” But both there and at DC, I think the understanding was that I would be a writer/editor — not a guy who edits his own stuff, that almost never works out — and, as a result of not having to edit my stuff, I got to work with Mark Gruenwald and Julie Schwartz and it was really fun and gratifying to collaborate with them. But I did Spider-Man and I was removed from that and Iron Man was a kind of fluke.

IRON MAN’S ALCOHOLISM

DO: I later found out that Mark Gruenwald shielded me, that his boss thought that Iron Man as an alcoholic was a terrible idea. There are people who think about alcoholism, “If you just get hold of yourself, dammit! Stop being so damn self-indulgent!”

MF: And that was how Tony Stark got sober, he just kind of white-knuckled it for a night and was fine.

DO: Yeah, if it were that easy, everybody would do it.

MF: I was wondering if that was a case of somebody not wanting to see — I’ve done scenes where we’ve seen Tony being a part of AA, have a sponsor and all that stuff — but, going back and looking at that early stuff, this was clearly editorial mandate: Nobody wanted to see Tony at an AA meeting, he just had to stare out of the window as it rained for an evening and he would be fine come daylight.

DO: Yeah, well, the first Iron Man story I did was a fill-in and Dave Michelinie had established the drinking problem in the continuity. I opened on Tony having a dream that he’s in the Iron Man suit, but he’s drunk and then you turn the page and he’s waking up, saying, “Wow, what an awful dream.” Steve Ditko did a great job on the rest of the story but we ended up having Marie Severin drawing that one page. There are people who think that heroes should never have serious flaws. I don’t think they should be jerks, the word “hero” is from the Greek “to serve and protect” and I think that has to be an element of it. But, having a guy overcome something like an addiction or a terrible flaw seems to me to enhance his heroism and I think Gruenwald’s boss was of that school or something like it.

We — Mark and I — if we had to do it again it would be six issues shorter. I think we did stretch it too far. There were a couple of other glitches but, basically, it was pretty successful and we got a lot of praise from rehabilitation organizations. So, what’s Tony’s drinking situation these days?

MF: Well, he’s onto a bad patch, but I’ve written him as being, basically, a dry-drunk. I don’t know that I want to get him drinking again, but I want to show him not asking for help — that’s been a big deal for me — and so this has been him as an arrogant, headstrong, “it’s OK, I can keep it together, I can fix everything” — coming from that sort of place. So, he’s learning the hard way that that is not, in fact, the case.

DO: Did you have a sense of the movies moving in the direction of more —

MF: My sense of having talked to the guys is that it’s going to be an issue, but I don’t think they’re ever necessarily going to do a Demon in a Bottle kind of story — that takes it into a different place than you can comfortably handle in a summer blockbuster. So, I think it will remain an issue and, if you’ve seen that first film, he clearly enjoys being in his cups a little bit. So, I think it’s going to be there subtextually and I don’t know how fine a point they’re going to put on it, but it’s definitely informing how they’re handling the character. In the casting alone, they’re acknowledging —

DO: Oh yeah!

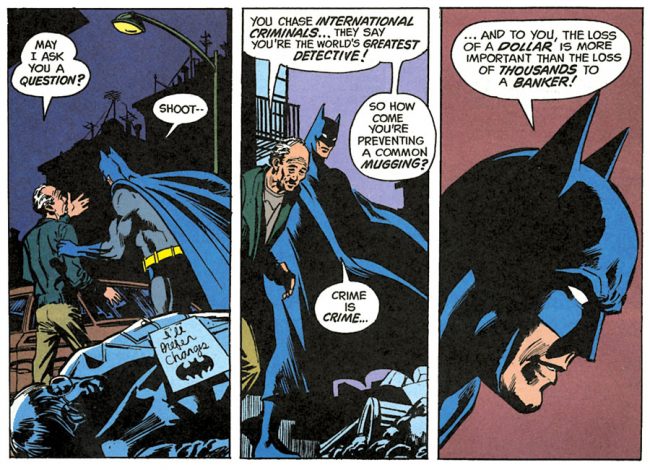

MF: This is maybe an interesting segue, but you very much are known for bringing in cultural and topical and political relevancy to the mainstream at a time when it might not have been a clean fit. Whether it’s Green Lantern/Green Arrow or any of this stuff — tell me about urging comics to grow up a little bit, or to deal with issues a little bit more complex and complicated than: “Ooh, Dr. Doom!” or “Ooh, Joker!”

DO: Or, “Who is this guy?” on page 22 and you turn it and it’s a full-page shot of Viktor von Doom! [Laughter.]

MF: Exactly, but you were very instrumental in turning —

DO: So they tell me and that’s very gratifying to hear, though I will disabuse anybody of the notion that Neal [Adams] and I were the first. There are some Superman stories that are socially conscious — in the way that Warner Bros. movies were back then —

MF: Right, the “I am a fugitive from a chain gang” school of —

DO: Yeah and the last year I had an editorial job, I was living here in Nyack and it’s an hour and 15 minute drive, so I listened to a lot of old radio shows and the Superman radio show was remarkable. The writer in me responded to it: “Wow! They establish everything you need to know every day without slowing down the story.” There were also a number of them that were really socially conscious.

MF: There was a K.K.K. story, is that correct?

DO: I think so, and there was an anti-Semite story.

SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND COMICS WRITING

DO: My own memory of my first glimmering of social consciousness was hearing — as maybe a 6-year old or 7-year old — Superman on the radio telling me that the difference in skin color was only because of a chemical called melanin and people were all the same. I had never heard anything like that. My parents — I don’t know how they avoided being bigots, but they did. Well, thing is that some people don’t know — they’ve never known a black man or a Jew — and the only information they have comes from tainted sources, but they don’t know that the sources are tainted. Anyway, that didn’t rub off on my parents, but that was the first thing I can remember hearing about this racist problem. Then, at Charlton, I did a one-shot called Children of Doom, which was a pacifist-oriented story and, as the Justice League writer, an ecology-themed story based on that river in Ohio that actually caught fire.

MF: My grandmother lives on the muddy banks of the Cuyahoga River I will have you know, sir.

DO: So, you know all about that?

MF: Sure, sure. And, as a matter of fact, I just bought Children of Doom at the last convention I went to, which we can get into but, please, continue.

DO: Well, Neal and I became flavor of the week at DC and, similar to what happened with Batman, Julie [Schwartz] said, “We want to continue publishing this title; it’s not doing well —

MF: This is really the aftermath of the show being canceled and the camp stuff not working.

DO: Yeah, that was Batman — suddenly camp was as dated as button-hooks and I had to come up with a new concept. But, with Green Lantern/Green Arrow, it was just, you know, “this thing is dying... Whattaya know?” Well, I had fooled with Ollie’s characterization in Justice League, I had taken his fortune away from him so that he wasn’t just another clone of Bruce Wayne. I was really, sincerely involved in the peace movement and the civil rights movements and I was living on the Lower East Side, surrounded by that world. So, there seemed to be no reason not to try something that would combine my comic-book writing with the real-life concerns that I had as a citizen, a parent, a veteran and all that stuff. I don’t think that Julie Schwartz even mentioned it to his bosses — it was such a loosey-goosey business back then that I think editors pretty much did what they wanted. Of course, you had to worry about the Comics Code but, as for the rest of it, we just did it. I assumed — I didn’t know — that Neal was going to do the art because he had not been a Green Lantern guy, but I think I first saw his proofs in Julie’s office and I was blown away particularly by the last three panels of the first chapter. I think he did a brilliant job and then, suddenly, journalists started paying attention.

The first story ran in the Village Voice and did not mention Julie, Neal or me — the guy who gave the interview might not have known what the hell he was giving an interview about — for whatever reason, that changed and I was getting the same 15 bucks a page that I was getting for writing Super Friends. But, Neal and I suddenly found ourselves getting interviewed and seeing our names where comic-book writers’ names don’t normally appear and we were aware, on some level, that we had pushed the envelope. I am looking at a hardcover edition of those stories that was published a few years ago — I don’t think either of us, in a million years, would ever have believed that that would have happened. Conventional wisdom was that the audience turns over completely every three years, so we think, “Well, the average comic book is forgotten in a year. Maybe it’ll take ’em two years to forget this one or this bunch.” But they did stick around.

MF: Were you aware when you were writing it that this was pushing it or did it just naturally happen? Was it a conscious decision to cross that street?

DO: Well, it was conscious decision to incorporate real-life social concerns. I guess we knew that that might ruffle some feathers and it did: We heard stories of the comic books not getting off the boxcar in certain cities because authorities objected to the content. We got some nasty letters, but the vast majority of the response was really positive and it didn’t save the sales thing. In those days, editors never saw sales figures so you never knew why a book got canceled. In my stint as a freelance editor, I knew that they could not have sales figures on some of the stuff that got shot out from under me. In those days, you got preliminary figures three months after off-sale and reasonably accurate figures in nine months. So, if something has had only two issues for sale and they say, “Bad sales,” you know that can’t possibly be right. So, after 14 issues, Julie said, “We’re going to continue it as a back-up in The Flash but the book itself is folding.”

“OK — onto the next thing. What am I going to write for you next week, Julie?”

NOW VERSUS THEN

DO: Do you get much editing?

MF: I’ve been very lucky, I have very good editors. I feel like I have guys who I workshop ideas with and who will make them sound better and make me look like a much better writer than I am. I’ve had a very easy time of it, really. My editorial relationships have been really conducive and really terrific and I feel that they’ve made me a better writer just through working with a good editor. I have no problems being edited, I have trouble with the stupid stuff, but the meat of it has been great and I’ve worked with some really great guys who have a terrific instinct for story. As I’ve come from an indy-art-school world where it’s very loosey-goosey and make-it-up-as-you-go, I’ve been lucky to work with guys who have helped me focus and narrow it in a way and I think the writing is better for it. People have horror stories, but I think I’ve been really lucky.

The film and animation stuff I did took me to advertising and I don’t do well with being art-directed by people I disagree with, especially on aesthetic issues. So, I don’t know that I’d respond well to a heavy editorial touch — mentally, emotionally, I don’t think I’d handle it well. I’ve been lucky that people have liked what I’ve wanted to do and have supported me, so I’ve had a pretty easy time of it.

KV: I have two questions about that. One: Are you able to avoid continuity-heavy projects, or how do you work with that? And my second question: You also do creator-owned work, so obviously that has to be fairly lightly edited, or maybe not?

MF: Oh yeah, that’s pure punk rock, you know? Garage-rock stuff: If it sounds right, do it. What’s interesting, though, is that I’m discovering that the more mainstream stuff that I do, the more I’m able to clearly articulate what I want to do sooner. I always felt that the way I wrote was like trying to catch butterflies with a stick covered in honey — running through and trying to see what I could get at the end and sometimes there are the right butterflies and sometimes there are the wrong ones. You have to run around like a lunatic to get a stick covered in butterflies and then you’ve got a story. I’m getting smarter about catching them.

Continuity: I think that continuity’s the devil. [O’Neil laughs.] I’m a fan of consistency — I think consistency is the watchword. Continuity? I mean, I’ve been reading comics for 30 years now, my parents have been reading comics as long as I’ve been writing them professionally and any time I’m in sticky territory where I’m not sure my folks are going to be able to follow what’s going on, it’s like a little red flag goes up. So, I try to make things as accessible as humanly possible and as consistent with the history and the continuity. But continuity-heavy stuff — and I write [Uncanny] X-Men, I am in a continuity minefield many days of the week and I try to avoid that exclusionary approach, even when you’re wrapped up in these big crossover events or when the currents of the macro-narrative are flowing in a certain direction, I still think there are ways that you can write and be as accessible as possible to somebody. I was told that Stan Lee always used to say that every comic is somebody’s first comic. While I’m not a fan of characters speaking in logos, spelling out for everyone what their powers are and what they do every third panel, I think there’s a way that you can write these stories to make them accessible to newcomers and make them satisfying to people who have been reading.

DO: And the lack of accessibility is the single biggest complaint that I hear from intelligent people who like comics. Once, when writing a novel, I needed a main villain’s name — and it was one of the biggest deals there was at the time — and I couldn’t get his name. This was the major antagonist that year. I finally called up another writer and said, “You did some of these scripts. Who is this guy?” So many editorial people assume that the audience has been reading this stuff and remembering it for 30 years. It’s a terrible technique. It’s one of the things that Shooter insisted on that I agree with — if you’re good, you can integrate what they need to know about what’s happening in front of them into the ongoing narrative: but, if it’s a question of — as writers of my generation used to do — stopping on page three to explain, well, that’s better than nothing.

MF: Yeah. Well, it’s true, now that collection and trade-paperback sales are such a nascent sales model, what works in a 22-page magazine every 30 days, might read like garbage if Reed Richards is reminding everyone that it was cosmic rays that gave him these fantastic powers every 22 pages. It’s going to be like Memento or something. There are ways if you’re conscious and cognizant of it — the Iron Man book I write was launched when the movie came out and I didn’t have any more special access to any information about the film than anybody else did. Indeed, I saw the trailer the same weekend that everybody else saw the trailer and that was all I knew apart from what I’d read in Variety about who had been cast. I just tried to make as many intuitive guesses as I could about what the film would be. What I saw as my mission for that first storyline was that I needed to write a book for people who had been reading Iron Man their entire lives and for people who come to a comic store the Saturday after they saw Iron Man Friday night and want to check out what’s going on with the Iron Man comic. So, how do you get people who only know the comic, how do you get people who only know the movie and how do you synthesize a way [to get both]?

DO: What you described is exactly the right way to approach something like that and, if you don’t, these people will pick up a comic book and they won’t understand it and they’ll say, “This is not for me. I don’t like comic books.” They probably won’t think about it enough to realize, “I might like comic books, but it’s easier to understand the first 10 pages of Finnegans Wake.”

MF: James Ellroy is a favorite of mine and he used to live in the Kansas City area and he would do his book launches at the little indy bookstore. So, I used to say, “Oh, when I have something written, I’ll go and give it to James Ellroy. Won’t that be neat? I’ll be able to tell myself that James Ellroy is reading my little crime comic.” But then I read in an interview that he had said, “I can’t make sense of comic books, my eyes just don’t know where to go.”

And he wrote some of these operatically complex novels, but presented with that early- to mid-late-’90s visual gobbledygook, he just didn’t know what to make of comic books. So luckily, I spared myself the embarrassment of my idol sneering and brazenly tossing my stuff into the garbage can next to him. When James Ellroy can’t follow a comic, there’s something fundamentally wrong.

VOICE

KV: You both write very clear, but very dense stories. One thing I want to talk to you both about is voice, because I remember you, Denny, saying in your ’78-’80 interview in the Journal —

MF: I was 3: I remember speaking about Crayons a lot. [Laughter.]

DO: Well, part of it is, insofar as this is possible, subtract the ego from the process. Any time the work becomes about you and not about the story you’re telling or about the problems you’re solving, you’re probably going to screw up. So, it’s a lonely gig we have. You can get help before, you can get help after, but during it’s you and that keyboard in that room. And that’s good! It should never be about me. I’ve probably used every significant experience that I’ve had in my life over the last almost-50 years of doing this, but I’ve tried not to ever put myself on stage, except maybe as a background figure in a crowd scene or something like that. It just gets in the way of doing the job, Alfie Bester said, “Among professionals, the job is boss.” If it becomes about my life, is that true anymore? Unless the conditions of the assignment are to write about your life — that hasn’t happened yet … Matt?

MF: Yeah, I’ve been nodding the entire time. At the end of the day, the job is the boss, man. Of course, personality and belief and perspective, all that stuff will come through in the work. To hear your involvement with the Catholic Worker movement and the Civil Rights movement, knowing your work, is absolutely not a surprise. Obviously, yourself will come through like that, but I just want to say what you said again, only first [laughs] — it’s amazing how inarticulate I’m becoming while talking about my process — it’s you sitting alone in a room and sweating these things out.

DO: Yeah, it’s one of the downsides of conventions and things like that.

MF: I find that actually going to conventions or any kind of professional event, there’s a warming-up process: I have to remember how to be social and how to talk to people and how to get a game face and get out of the office for a little bit. I have a 2-year old now and it’s one of the great joys in my life to come downstairs and hear him shout for me and, immediately, I can take the job off, leave the work jacket up in the office and go and just be dad for a while and play and get away from it. It’s such a solitary thing, but I enjoy that. I like to work, I like feeling driven, I like feeling like a professional, I like feeling like a grown-up and I like being competent and dependable and reliable and all those things.

DO: And you meet your deadline, you can feel so smug! [Laughter.]

MF: Exactly! I’ve been thinking a lot about Michael Mann movies lately — as berserk as the man might be in real life, he makes these movies about very dire professionals who tend to work very dangerous jobs with lots of guns and great suits. I think I get that — being someone whose job it is to push buttons on a keyboard and to make these words up in your head, I understand the appeal of wanting the “drama of the professional.”

DO: Yeah, I wonder if that isn’t why some writers — Hemingway, of that ilk — made such a big deal of being macho. Because what we do, as Larry Block says, is basically the same job as a stenographer, only at least a stenographer has somebody else in the room.

MF: We’re poking at the fire with a stick and making stuff up, you know?

DO: People who think that writing is a tough job ought to try driving a cab or working on an assembly line.

MF: Yeah, dig a ditch for a week.

DO: Even something like selling subway tokens — you’re breathing in terrible air and you’re bored for 40 hours. This is really pretty good!

MF: This absolutely beats working for a living.

DO: Yeah! You go downstairs — in my case, I work an hour a day because I’m working on something without a deadline — but even when I’ve been working tough deadlines, it’s an air-conditioned room in a swell little house.

MF: I don’t have tuberculosis: it’s pretty good for me. I’ve been boasting that I’ve never had a job where I’ve had to put on a nametag. I’ve never had a job where I’ve needed to wear a paper hat. I’ve only almost burned my face off with a deep fryer once. I always suspect, too, that that’s why there’s such romance and drama around the blacklist because that’s a time where writers really were in a time of danger and there was like, “Woah, these are big stakes. There’s a real importance happening there,” and I think there’s a drama and a romance because, for the most part, we sit in a room and make stuff up all day. So, for the one time, when Congress wanted to interview writers — oh my God, that’s so dramatic!

DO: And some of them put their asses on the line and paid their dues on principle.

MF: And made real moral choices.

DO: Dashiell Hammett was dumped from everything: He had a radio show and suddenly he didn’t have a career. I remember I used to listen to Sam Spade: Private Eye on the radio and then one week, with no warning, it became Charlie Wild: Private Eye. Obviously, they had a script by Hammett and they went and crossed out the proper nouns. He was one of them, and then he enlisted in the Army at age 42 when he was safe and he was one of them that really got screwed over by that whole, insane, vicious McCarthyism.

MF: And more recently, think about Salman Rushdie.

DO: Sure, sure, sure.

MF: Or even, hell, the Bush-Cheney administration, when you had Ari Fleischer smacking Bill Maher down from the White House press briefing room. I think it goes back to what you said, earlier, that these are 22-page stories, and they’re fun and they’re light, and they come and they go. Taken on its own merits, it’s a small thing, and we’re telling the same stories that have been told since the beginning of history. This is not grand drama.

DO: And there really are only seven plots.

MF: I actually just called the title of this X-Men story, “Somebody Comes to Town, Somebody Leaves Town.”

Continued.