Obligatory Warning. These notes are about some of the recent books of Daniel Clowes, which tend to have twisting plots rich in surprises. I’m working from the premise that anyone browsing through these notes has already read the comics and so I’ll be free with analyzing various plot elements.

A Good Time. It’s a good time to be a Clowes watcher since he’s been on a publishing roll. Last year saw the publication of Wilson, and this year we have Mister Wonderful (an expanded and re-mastered edition of a story first serialized New York Times Magazine), The Death-Ray (a soon-to-be-released book version of a story that originally appeared in Eightball #23), and a new paperback edition of Ice Haven. Of the four books, Ice Haven is likely to stir the smallest fuss because it offers the least new material (the front cover, back cover and spine have new art but otherwise it is the same as the 2005 hardcover). But I think these works benefit from being read (or re-read) together since a set of recurrent themes and artistic strategies ricochet through them, making for a very cohesive oeuvre, although also one in which each book has a carefully demarcated individual identity.

The Impossibility of Ranking. I was talking to one of the most aesthetically-astute comics folks around and he said that he preferred Wilson to Mister Wonderful, although of course he enjoyed both. I myself find it impossible to make judgments of this sort since each of Clowes’s recent work has its own peculiar charm. Although all these comics are clearly from the pencil and pen of the same artist, these works are very distinct. I don’t know if this is a self-conscious goal or just his instinctive procedure as an artist but Clowes seems to approach every new book as a fresh canvas, as a challenge to do a type of story he hasn’t before or to rework a longstanding thematic concern in a fresh way. I can’t think of any other cartoonist – except perhaps for Crumb – who has displayed quite the storytelling range of Clowes.

Fragmented Storytelling. Ice Haven is Clowes's first experiment with fragmented storytelling, told in brief, bite-size segments that are no more than four pages long. These segments are stylistically diverse, ranging from the antic anthropomorphism of “Blue Bunny” to the noirish melodrama of the Mr. and Mrs. Ames segments. As Nick Mullins has noted, the storytelling is also highly elliptical: key events (the kidnapping and release of David Goldberg) take place off panel. Clowes would return to this mode of fragmented, elliptical and stylistically various storytelling in future works like The Death-Ray and Wilson. In recent years other cartoonists – Seth, Chris Ware, David Heatley – have also tried their hand at fragmented narratives. In explaining this mode, Clowes has cited the influence of film-making (he worked on Ice Haven after doing the Ghost World film). In film, editing plays a key role in the act of shaping the narrative. Fragmented storytelling allows the cartoonist to have the luxury of editing, something that is much harder to do with a continuous narrative. Clowes has also mentioned the influence of the newspaper Sunday comics supplements of the late 1950s and early 1960s, where very stylistically varied strips (say Mary Worth and Henry) would be stacked together on the same page or in the same section.

But perhaps fragmented narratives are also rooted in Clowes’ own earlier practices as an artist. The much-cherished first few issues of Eightball all featured a variety of short works done in an impressive diversity of styles. Typically an issue would include a chapter from the nightmarish thriller Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron coupled with a page of winsome and baffling illustrated non sequiturs from The Duplex Planet as well as a bile-filled Dan Pussey story and a ranting monologue. A lot of the energy of an Eightball comic book came from seeing different styles, tones, genres and voices rub against each other in the pages of the same comic.

Fragmented narration allows Clowes to tell a single unified story (as required in the age of “the graphic novel”) while reviving the energizing friction of stylistic variety. Of course, the format of Eightball itself was influenced by both the humor magazines Clowes grew up on (Mad and Cracked) which contained within them many discordant styles and also the one-man anthologies of Robert Crumb (for example Hup) which also allowed the artist to house his many storytelling modes and artistic concerns in a single package.

Movies versus Comics. Clowes’ script for the Art School Confidential movie was an ambitious attempt to deploy one aspect of fragmented storytelling to film: tonal variety. The episodes in the film vary from a tone of lacerating mockery to moods that are much more somber, introspective and, at times, violent. But this tonal variety makes for a jarring moving-watching experience. The shifts are too abrupt and there is no visual language cuing us to have different expectations for each individual episode. But in his comics Clowes can get away with great tonal dissonance because each episode is drawn in a different style, which makes the discontinuity from episode to episode easier to grasp. Theoretically, it should be possible for a film to have the tonal variety of a Clowes comic but it would have to be a very daring and experimental film, one that has sequences fashioned in imitation of such divergent directors as Frank Capra, Chuck Jones, Sam Fuller, Stan Brakhage, and Woody Allen.

Form and Fragmentation. It could also be that fragmented storytelling is uniquely suited to comics, an inherently splintered art form that splits up visual action into discrete panels and fuses images with disparate texts (word balloons, panel narration, sound effects). Much of the “action” in comics has always taken place between panels and off panels, but Clowes (along with Messrs. G. Gallant and F.C. Ware) has found a way to make stories that are much richer by foregrounding this experience of gaps and elisions, by forcing the reader to ponder the fact that what-is-not-drawn can be as important as what-is-drawn. Reading these fragmented narratives requires a heightened degree of readerly attention, one that requires a constant querying of artistic intent.

Detective Fiction. From Lloyd Llewellyn to Mr. and Mrs. Ames, Clowes has often featured detectives in his stories, not to mention many amateur clue-hunters such as Clay Loudermilk and David Boring. Another variation of this are the characters who are not quite detectives or clue-hunters but like to spy on other people: Random Walker, Violet, and Charles in Ice Haven are good examples. Fragmented storytelling forces the reader to become a detective. Each fragment is an incomplete bit of evidence and the full meaning of a story like Ice Haven or The Death-Ray involves guessing at the larger story these clues point to. By making the reader act as the detective while reading a fragmented narrative, Clowes has found a new way to fuse form and content.

Blinkered Chivalry. In an earlier set of notes I’ve remarked on the fact that several of Clowes’ stories are variations of the myth of Orpheus, with the hero descending into the underworld to redeem his lost lover. But perhaps another way of saying this is that Clowes often features men animated by a blinkered chivalry, keenly intent on rescuing some fallen or endangered woman (even if she doesn't want or need redemption). The detective Mr. Ames falls into this pattern, as does Marshall in Mister Wonderful (the endpaper of this book is a hilarious tableau of chivalric fantasies). Or consider Wilson’s attempt to reunite with his ex-prostitute wife and given-up-for-adoption daughter to form a family is an extreme example of the chivalric hero trying to get his way through sheer force of will. As his name indicates Wilson (will plus son) is willful son-of-a-gun, a man who, on the death of his father, tries to will himself a family. A kind of obtuse romanticism also fuels the actions of the main characters in Velvet Glove and The Death-Ray, and indeed even as far back as some of the Lloyd Llewellyn stories (such as “Hound Blood”). If I had to locate the central themes in Clowes’s work, it would be blinkered chivalry and love triangles.

Prostitutes. The flip side of blunderbuss chivalric men are the women in trouble, who are often (Chester Brown please take note!) prostitutes or sex workers of some sort. In Ice Haven the self-romanticizing detective Mr. Ames sits in a bar and sees a street hooker out in the rain. He thinks to himself, “I’m attracted to people who are in trouble. I can’t help it; I want to save people … I’m one of the good guys.” (Ames's use of “people” is a nice bit of euphemism since it is the prospect of women in trouble that gets his engine started). In Mister Wonderful Marshall is brought out of his celibate slumber by a fling with a woman who seems to be a borderline prostitute who he tries to assist and who ends up bilking him. And as mentioned Wilson’s former wife also worked in the sex trade. One can see a skewed version of this theme in Velvet Glove where the hero’s former lover now makes very bizarre porn movies.

Speaking of Chester Brown. Mister Wonderful arrived shortly after Paying For It, and I read the books in quick succession so they are conjoined like Siamese twins twins in my mind. On the cover Mister Wonderful is described as “A Midlife Romance” which actually describes the hidden plot of Paying for It. As Seth astutely notes, Chester Brown’s decision to become a john was the product of a “midlife crisis.” Mister Wonderful is the story of a middle-aged schlub who, after a bad break-up, has given up on romantic love. A chance encounter with a borderline prostitute, a “transformative” human event that awakens his romantic feelings and gives him the strength to go on a blind date overly-fraught with romantic expectations on his side. Paying for It is the story of a socially-awkward soul who, after a hard break-up, gives up on romantic love. After a celibate spell he decides that the services of prostitutes will solve his sexual needs. Becoming a john turns out to be a transformative experience, surprisingly reigniting the john’s emotional life so that by the end of the book he falls, against his own conscious plans, in love with one of his call girls. Both books deal with the mid-life theme that has become a major concern for alternative cartoonists.

Romance Comics. Clowes has cited 1950s romance comics as an influence on Mister Wonderful. I think the fingerprints of romance comics can also be seen in the Violet Van der Platz sections of Ice Haven, with her pinkish and overheated letters to her lover Penrod. There’s an element of romance comics also in The Death-Ray with one-sided love letters. In general, the impact of romance comics on alternative cartoonists has been under-analysed. There has been endless commentary linking contemporary art comics back to Kirby, Toth, Barks, and so on. But for some reason, critics still find romance comics icky and haven’t noticed the evident impact they had on the early undergrounds (see Young Lust) and the Hernandez Brothers (it’s right in title: Love and Rockets). I’d also argue that the Charles Burns of Black Hole is at least as indebted to romance comics as he is to horror comics (or rather, the sensibility of romance comics as refracted through 1960s Marvel monster and super-hero stories). One reason romance comics get a short shrift is that comics criticism is still inflected by the concerns of superhero fandom, a largely male subculture that tends to dismiss genres that appeal mostly to women. But romance comics were not just repositories of kitsch, they also provided valuable narrative strategies and tropes that contemporary artists can recuperate. Clowes’s re-purposing of romance comics is of a piece with his general predilection for playing with genres (superhero comics in The Death-Ray, hard-boiled detective fiction in the Mr. and Mrs. Ames episodes, funny animals in the “Blue Bunny” segment).

Pepper and Pippi. Wilson’s beloved dog is named Pepper, his troubled and troublesome ex-wife Pippi. The fact that the two names are near-homophones reveals something about Wilson’s trouble with women. He wants a wife who is as utterly subservient, as unconditionally affectionate and as unspeaking as a dog. Tellingly, Wilson ventriloquizes Pepper’s “dialogue” just as he tries to manipulate Pippi into doing something she has no heart for (restarting her family life with Wilson and their daughter). Wilson chides Pippi for being so quiet but when she does offer her opinion he shoots her down with a typical Wilsonian put down (“Hey, it talks!”). Wilson's affection for Pepper is one of his more endearing traits but it looks much more troublesome when linked and compared to his treatment of Pippi.

The Best Critic. The second best critic of Clowes is Ken Parille. The best critic of Clowes is Clowes himself. I’m not just talking about the interviews he gives (which are invariably shrewd, informative and helpful) but also Clowes’s habit of embedding exegetical clues in his books, hints on how to read and interpret the text before us. On page 21 of Ice Haven we overhear a high school English teacher explain an assigned text: “his city is a living organism, no less, and perhaps more, than any of his ‘human’ characters.” That’s not a bad description of Ice Haven as a book, a story where the town, even though filled with isolated misanthropes, still has a communal identity. Other useful hermeneutical hints are provided by the comic book critic Harry Naybors, who is both a character in the story and a commentator on it. Naybors is meant to be a figure of fun (he walks around in his underwear, is shown urinating and, worst of all, owns a copy of Elfquest) but his ideas on comics are quite sound and a good launching pad for discussion. This tendency to preempt and direct the task of criticism places Clowes squarely in the tradition of the high-modernist novel. Joyce and Nabokov also wrote books that contained within them guides and suggestions as to how they should be read. Implicit in dense books like Ulysses and Pale Fire is the vast exegetical apparatus that will grow up around them. John Updike once described himself as being "intoxicated by the wine of self-exegesis.” The same is true of Clowes.

Advice from Harry Naybors. “As always, it behooves the critic to examine the intimate details of the author’s life and to strip-mine his body of work for evidence of thematic continuity, et cetera.” Well, I don’t know about prying into Clowes life, but there is certainly value in looking for thematic patterns.

The Leopold and Loeb Pattern. The famous Hyde Park killers Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold are characters in Ice Haven. Loeb is described as “affable and gregarious” while Leopold is “a quiet, prickly honor student.” Leopold and Loeb have a very dangerous friendship, the type described by the French as folie à deux (or “a madness shared by two”). As separate individuals they might be mildly misanthropic but when they come together a sick symbiosis pushes them to transgressive acts that neither alone would have dared to imagine let alone to commit. Both in Ice Haven and in his other works, Clowes has often returned to Leopold-and-Loeb type relationships, where the aggressive extrovert is teamed with an sullen, sometimes silently resentful, introverted partner. In Ice Haven we have Carmichael, who tries to be the Loeb to the quieter Charles, Violet Van der Platz and Julie Rathman (typically, the Loebish Violet is so verbally profuse that we barely get a hint of Julie’s story, although it involves a teen pregnancy), and Mr. and Mrs. Ames. Elsewhere there is Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer in Ghost World, Wilson and Pippi in Wilson, and Louie and Andy in The Death-Ray. Even Zubrick and Pogeybait fall into the introvert/extrovert pattern.

Twos and threes. Related to the Leopold-and-Loeb pattern, in a 2004 review of the comic book version of The Death-Ray I wrote: “At first, Andy is reluctant to use his newfound powers, but he is egged on by his cocky friend. As always, Clowes is very good at portraying the dangerous Bonnie-and-Clyde dynamic of friendships based on a quarrel with the world, where the twisted synergy of a duo pushes them to do things together that they would never dare alone. (In Clowes’s universe, everything comes in twos or threes. Two is the number of friendship, three of love triangles. The most recurrent relationships in Clowes’s comics are tight, almost, claustrophobic friendships and love triangles that erupt into violence and sometimes murder).” Clowes keeps returning to the interplay between twos and threes, between couples (where homosocial or heterosexual) and love triangles.

Internal/External, introvert/extrovert. The astute critic Harry Naybors sees the interplay between the internal and the external as inherent in the very form of comics. As he notes, “There exists for some an uncomfortable impurity in the combination of two forms of picture-writing (i.e. pictographic cartoon symbols vs. the letter shapes that form ‘words’) while to others it’s not that big a deal. Alleged awkwardness aside, perhaps in that schism lies the underpinning of what gives ‘comics’ its endurance as a vital form; while prose tends toward pure ‘interiority,’ coming to life in the reader’s mind, and cinema gravitates toward the ‘exteriority’ of experiential spectacle, perhaps ‘comics,’ in its embrace of both the interiority of the written word and the physicality of the image, more closely replicates the true nature of human consciousness and the struggle between private self-definition and corporeal ‘reality.’” If Naybors is right in suggesting that the form of comics embraces both the internal and the external, then it makes sense for a cartoonist to constantly monitor the relationship between introverts and extroverts, between characters who are all psychology and characters who are all action.

Monologists and Silent Types. Another way to divide up these characters is to make a distinction between chattering monologists and the more silent characters. In Ice Haven the big talkers are Random Wilder, Harry Naybors, Carmichael, Violet, Leopold, Vida, Mr. Ames. Characters more chary with words include David Goldberg, Ida Wentz, Mrs. Ames, Officer Kaufman, Penrod, Kim Lee, George, Julie Rathman. Charles is an interesting liminal figure, a middle-man or middle-child of sorts. He’s relatively silent when around the pushy loudmouth Carmichael but become hyper-vocal around the nearly mute George. As a result of Charles we see that the division between monologists and silent types is not absolute but relative to social situation.

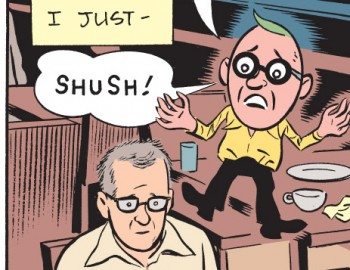

Marshall and Wilson. The introvert/extrovert theme plays itself out as well in the similarities and differences between Marshall and Wilson. They have some superficial commonalities: both are middle-aged, Oakland based, living dead-end lives, and looking for a life partner. Both have a scar-picking scabrous wit. But Marshall is an extreme introvert while Wilson is an over-the-top extrovert. Everything Marshall thinks, Wilson says. Marshall can’t listen to other people because he’s too busy talking to himself. Wilson can’t listen to other people because he’s too busy talking, period. In Marshall, cynicism and self-loathing are directed against himself, in Wilson the quarrel is with others and there is a distinct lack of self-knowledge. Marshall is paralyzed by excessive self-consciousness, Wilson is dangerously lacking in self-awareness. What would happen if the two were in the same book and teamed up? It would be another Leopold and Loeb combination.

Bifurcated characters and Doppelgangers. Perhaps another way to think about the introvert/extrovert pattern is say that Clowes likes to bifurcate his characters or split them into several selves. Rebecca Doppelmeyer isn’t just Enid Coleslaw’s friend, she is also (as her name indicates) a doppelganger. She is a variation on Enid, somebody Enid could have become with a few changes in her life. Doppelgangers are especially evident when you see characters with similar names as in Carmichael/Charles (Carmichael's sexual boasting about Paula and tough guy talk being an outward expression of Charles sexual turmoil and anger) or Violet/Vida (both young women who come into Ice Haven from outside, both who use their writings to express their unfulfilled desires). Violet has another doppelganger in Julie Rathman, who is more than just a silently listening friend. Julie dramatizes what could have happened to Violet (teen pregnancy on top of desertion) rather than what did happen. In Mister Wonderful, this sense of divided self is visually externalized in the form of a floating super-ego who is stylistically similar to the Great Gazoo from the Flintstone and who occasionally offers Marshall advice (not all of which is welcome or wise).

Nabokov and Freud. To speak of divided selves and doppelgangers is to enter into Freudian territory. Clowes has played with Freudian ideas in many works (see the cover of Eightball #17 for one particularly explicit example). Intriguingly, Clowes’s other polestar is Nabokov, who was second to none in his hatred for the “Viennese quack." Freud and Nabokov are not just dueling deities in Clowes' imagination, he has miraculously found a way of combining them. Clowes narrative strategies are Nabokovian: he tries to keep readers on the ball by hiding information and being as indirect as possible. But the clues that Clowes scatters in a Nabokovian-fashion often point to a classically Freudian interpretation of character action, with especial emphasis on the family romance of mother, father, and child.

(continued)