I’ve followed Liz Suburbia’s comics for years, snapping up each $2 issue of her series Cyanide Milkshake or her other B&W photocopied zines whenever I saw her or her friend and distributor, Kevin Czapiewski of Czap Books, at a fest. Liz’s drawings of sweaty, hairy people with curves engaging in gleeful, consensual sexuality helped me connect with my own body.

I’ve followed Liz Suburbia’s comics for years, snapping up each $2 issue of her series Cyanide Milkshake or her other B&W photocopied zines whenever I saw her or her friend and distributor, Kevin Czapiewski of Czap Books, at a fest. Liz’s drawings of sweaty, hairy people with curves engaging in gleeful, consensual sexuality helped me connect with my own body.

Her debut graphic novel from Fantagraphics, Sacred Heart, follows a teenage girl named Ben Schiller who lives in a religious community in Alexandria, Virginia. All the parents have disappeared, leaving the teenagers to fend for themselves. Kids still show up at school, but just to hang out, acting casual while clinging to what little structure they can. It recalls Miriam Toews’ novel A Complicated Kindness, another story about an outsider teen dealing with religious oppression, if protagonist Nomi Nickel lived in a semi-wasteland where it seemed like zombies or other supernatural horrors might descend at any moment. Liz blends the Bible, punk rock, the magical realism of the Hernandez brothers, and trashy teen girl revenge flicks into a subtle story that explores alienation, gender, consent, sexuality, and trauma.

I once hung up an issue of Cyanide Milkshake on my bedroom wall, open to a comic about Rogue from the X-Men. Rogue figures out sex; her powers make it so that she can’t touch or be touched by anyone without hurting them. Rogue says that she refuses to deal with jerks who treat her like damaged goods. She tries out a Skype jerk session, meets up with another girl both clad in latex, and gets tied up and explores impact play, all in her search, she says, “for a little sugar.” Liz brings this nuance, sensitivity, and playful openness to any subject she engages with. I wanted to interview Liz since meeting her and reading her work at SPX 2012, and I’m happy to bring you this interview, recorded over Skype while Liz was in the middle of preparations to bring Sacred Heart to SPX 2015. Liz made the book as part of a projected four-volume series, and I’m excited to see where the story goes.

ANNIE MOK: So you started serializing Sacred Heart as a webcomic, around 2010?

LIZ SUBURBIA: I think it was around New Year’s, right when I started working at the comic book shop.

MOK: And you were living in Virginia, or DC?

SUBURBIA: Virginia, the DC suburbs.

MOK: And you were how old, can I ask?

SUBURBIA: 25.

MOK: I went back to the archives and looked at the beginning of it. You had obviously redrawn the entire thing, and I remember when I heard that, I was like, ‘Oh my god, that’s Herculean.’ But I understand why you did it. It’s such a huge leap in your abilities from then to now. The first scene, when I look at it, is story-wise essentially the same. Ben goes under the bleachers and ogles this football player that she likes. Can you talk about the origination of the story and how it developed over time, and how it might have changed as you changed, as an artist and as a person?

SUBURBIA: When I started it, I didn’t have much of a sense of where I was going. I planned it as a loose bunch of stories that were all in the same setting. It came a long way to the point that it is now. Like you say, the art on the website isn’t very evolved. I chose to leave it up, so that maybe people can, uh [laughs] see how long of a process this sort of thing is. It doesn’t just come out of thin air. I had just started reading Gilbert Hernandez’s Love and Rockets. I had been into Jaime’s for awhile, but I started to develop an appreciation for Gilbert’s work and his take on it. I was reading him and thinking, “These are a bunch of loosely connected stories that don’t have a ton to do with each other, and I’m gonna do something like that, it seems like fun.” Not realizing, of course, that they’re all very interconnected. The longer I worked at it, and the more developed I became technically and as someone who thinks in terms of stories, it came together. And it’s really important that my publisher gave me the chance to edit it because some of the chapters online aren’t even finished. It was good to have a chance to mature a little, and still go back and do right by the story a little more.

MOK: Chris Ware has talked about how editing is one of the most important and most ignored parts of making comics. It’s considered very intuitive for prose and film, but for comics it’s a pain in the ass, and I think a lot of people just skip it. I’m happy to hear you talk about going back and making the story full, because I’m doing that with a story of mine right now, and it’s a weird process. What about Gilbert’s work inspired you back then? And you’re reading the first Palomar stories [at that time]?

SUBURBIA: I actually started with the Luba in America stuff, with Three Daughters.

MOK: That’s wild. That’s a wild one to start with! [laughs]

SUBURBIA: Yeah! [laughs] I’ve always been good about jumping into the middle of a story and rolling with it. I went back and read the earlier Palomar stories.

MOK: That’s such a huge element of Sacred Heart, a very well-played in media res element where there’s a big reveal at the end. Then when you go back [as a reader], it adds so many layers to the story.

SUBURBIA: I didn’t set out to do that, it just kinda accidentally happened. I don’t think of myself as a very strong writer. I never studied it or anything, I’ve really been learning as I went along. I guess there’s something to be said for the process of making it up as you go along and letting the story develop naturally from a lighter framework. This is the first big thing I’ve worked on, so I can’t tell you if that’s how I work, or if that’s just how this happened. But I guess we’ll see. [laughs]

MOK: Right up front, there’s so much about the process of physically writing and drawing that the characters connect with. There’s graff all over the water tower, then Ben writes with a stick into the dirt ‘Mom + Dad.’ Then she wipes it out and she writes ‘Butts.’ Then further into the story, one of the first things that Ben and her best friend Otto do is she tattoos his arm with this girl ‘Lola,’ this hot punk girl. Can you talk about what you get out of the very physical processes of writing and drawing?

SUBURBIA: I get a lot of exhaustion. [laughs] It’s something I’ve been doing my whole life. All kids draw from a young age. I don’t know if my parents were especially encouraging compared to other people, or if I just got positive reinforcement at school, but for whatever reason I kept with it. It was a good way to get attention [laughs] to stand out. We moved all the time and I was always the new kid, so I tried to get the other kids to welcome me into the fold, and if you can draw, everyone says, ‘Draw me this!’ And I think the kids who are the drawer kids, some of them go into doing tattoos for people, which is very similar to the ‘Draw me this’ thing.

MOK: Ben is on the edges of a lot of cliques, but she gets welcomed in, in a tacit way, when she does tattoos for people.

SUBURBIA: Sometimes it can lead to real friendships and sometimes it can be more proximity.

MOK: In that scene where she’s doing the tattoo for in group of friends, she’s on the edges. And it’s the same group who had been going, ‘Ben sucks’ and one guy goes, ‘Well, she’s okay, if you’re nice to her.’ [laughs] And that’s kind of the extent of what they think of her.

SUBURBIA: Yeah, a lot of teenage boy awfulness. But in their defense, everyone has an awfulness stage, I think. [laughs]

MOK: That’s something I find attractive about this book. There’s a cliché in art comics—Dan Clowes, Chris Ware—a very masculine approach, a Raymond Carver approach to depicting the “warts ‘n’ all” character of people. And then there’s the way you treat it. People’s flaws are integrated with their personalities, and it’s apparent that they’re on a path, at an difficult part in their lives. Their actions, as well as their bodies—I love this hairiness and lots of freckles, and cellulite—all these details are celebrated. And while some of these people do really awful things, it’s within the context of what they’re going through. Like with Ben’s sister literally being named “Empathy,” and then you find out what’s going on with her.

SUBURBIA: When I started this story, I was a lot closer to being outta high school. I didn’t go far from my last high school to go to college. I was still talking to a lot of the same people. And I think the age I started this was right around when people were starting to settle in to the paths they were gonna be on. People were going their separate ways, and the relationships that were standing the test of time were starting to show themselves. I started a high school-set story because I was feeling introspective about that experience, and as I’ve gotten older, working on it, and gotten more far removed, the perspective is… Growing up is really hard for everybody. Some people definitely more than others. And these kids are in this fucked up situation, and they’re making it work because there’s a lot of strength and resilience in kids that they’re not even conscious of. And sometimes awfulness is your strength, y’know? [laughs] It’s not an excuse for treating other people like shit, but when you’re young and you’re just trying to hang on, sometimes that’s just what you do. I developed a lot more compassion for the characters, even the... [laughs] even the terrible ones. The kids who die in the end, I’m not trying to punish them.

MOK: That feels really real to me, that idea that sometimes your awfulness is tied up with your resilience and your strength, because kids often have to get really tough to deal with a situation, just trying to survive and cope, and hopefully thrive. I love this relationship that Ben has with her little sister Empathy. They’re maybe two years apart, three years apart?

SUBURBIA: Around two… Penny, can I help you? [talking to the dog, who’s licking Liz’s face]

MOK: [laughs] I love this dog! Those eyes! They look just like your drawings! So, they have this relationship that’s tender in certain ways. They’re tied to each other, but also they’re separate in a very teenage way. I know when I was that age—my sister’s a couple years younger than me—I was breaking apart from her through childhood and adolescence because we were living in an emotional warzone. But also there’s this element with Ben and a lot of other characters who are teenagers, where they’re being thrust into an adult role, a totally inappropriate role of being a caretaker. And that’s taking a real toll on them. Can you talk about that as far as it relates to these characters?

SUBURBIA: I, um… [laughs] It’s interesting that you use the word “caretaker,” that’s what my therapist says. At 30, I’ve realized that a lot of my friendships have fallen into that. Not all of them. The ones that last tend not to. But that’s definitely a pattern of behavior that I have a lot of experience with, codependence or mothering, being someone’s fake mom. I didn’t set up to make Ben autobiographical, but that tendency came up naturally in the course of her character. Mostly through her relationship with her sister. Me and my family, moving around as much as we did, we’re very close-knit. We had to watch out for each other, and me and my younger brother and sister, we fought a lot, we clashed a lot, but we were also each others’ only friends. And me being the oldest, I did a lot of babysitting, a lot of [laughs] educating. We don’t have that relationship now, we’re all kind of on equal footing as adults. That dynamic reached its healthy conclusion. But it’s still one that’s easy to repeat without realizing it. If you’re meeting people from different circumstances, if you don’t have very good boundaries… [laughs]

MOK: [making air quotes] “What do you mean?”

SUBURBIA: [laughs] And that was a conscious thing in the book, that without parental guidance, these kids are stumbling through these relationships. They don’t have good boundaries, they don’t know about things like consent, or healthy friendships, or birth control… Some of them more than others. If you’re fending for yourself, psychologically, when you’re growing up, you learn through trial and error. Sometimes the consequences for that are big, and sometimes you emerge relatively unscathed.

MOK: And they’re also stumbling because of the terrible stress that they’re under. Which is that classic storytelling thing: you put characters in the most terrible situation possible, and then their inner natures reveal themselves by necessity. There’s a favorite story of mine from Cyanide Milkshake about you and your little sister. You two [as little kids] would be falling asleep, and you’d be terribly nervous, and you’d reach over and hold her hand over a gap of floor to the adjacent bed. I thought that was so sweet and real, and also interesting to think about in correlation to the characters—not that there’s necessarily direct correlations, but with some memoir elements in the characters—of Ben being a nervous person, and Empathy feeling a lot more confident, even though she’s struggling with her own demons. But to Ben, through most of the story, she seems to feel like Empathy’s part of the crowd, and she’s very much not.

SUBURBIA: That was, um… I hesitate to draw parallels between Empathy and my own sister...

MOK: [laughs] They’re not the same person! We wanna make that clear.

SUBURBIA: My sister’s a wonderful human being who’s got her life together. But I can see what you mean about that relationship coming out. I was a really nervous kid, scared of everything, and Leigh, my sister, was always really brave. Fearless socially, fearless as far as bodily preservation goes. She’s always had a lot of friends and she’s really smart, and she really lives her life. It’s something I always watched from afar and envied, and thought, “It must be so easy to be you.” Only in more recent years, she let me know, “It’s not always easy. I get depressed too, I just deal with it in different ways.” It looks different on me than it does on her, but we go through the same things. Maybe some of that came out in the book, where Empathy is someone who looks like she’s got it together on the surface, but what’s going on has affected her in deeper ways. And when you don’t confront that, sometimes it can come out.

MOK: What you say about watching your sister, I think that’s a classic artist thing, this quality of observation. I see that in Ben, too. Ben is perhaps a little judgemental, y’know, not for no reason...

SUBURBIA: [laughs]

MOK: But she is a central character who’s watching a lot of balls in motion. She’s looking at her best friend Otto, looking at their relationship as that changes, looking at Otto’s relationship with her girlfriend Kim before that happens. Which is a common thing for high schoolers, because you feel so little autonomy in those years. It’s like any other high stress situation, where you have to suss out relationships and observe, see what are the safe situations, and see where things are going. Can you talk about that, and how Ben deals with that?

MOK: But she is a central character who’s watching a lot of balls in motion. She’s looking at her best friend Otto, looking at their relationship as that changes, looking at Otto’s relationship with her girlfriend Kim before that happens. Which is a common thing for high schoolers, because you feel so little autonomy in those years. It’s like any other high stress situation, where you have to suss out relationships and observe, see what are the safe situations, and see where things are going. Can you talk about that, and how Ben deals with that?

SUBURBIA: I think that started more as a function of the storytelling than as a real character thing, because she’s our point of view character, and I wanted to build the world a little bit. I can’t speak for other people, but I know that’s how I try to be a human. Watch how other humans do it, and see if I can [laughs] do it too. You brought up the word “judgemental.” I’m definitely a judgemental person, for better or for worse. Which I think comes from being on the more observational side of things. That’s the quintessential alienated teen girl viewpoint, isn’t it? That she’s on the outside of things, and she only has the one friend. Everyone from Daria to Ghost World is all, “It’s me and my one friend against the world.” There’s some longing that folds into that kind of willful detachment.

MOK: What do you think it’s a longing for?

SUBURBIA: There’s the illusion that it’s easier if you fit in, or if you have a lot of friendships rather than putting the burden just on one person. But I think it can be difficult in a different way. For someone like Ben, who feels so much responsibility for her sister, and so much accountability towards her parents that she’s waiting on, that she chooses to stand outside because she doesn’t have the emotional bandwidth for that many people. There’s a line at the end where she tells Otto, “I can’t be responsible for one more person right now.” It’s kinda sad when that feeling of love, like, you only have so much to give. It shouldn’t be a burden, but sometimes it is. It doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It takes a lot of growth, a lot of maturity and development as an adult to get to the point where you can manage that feeling—not discount it completely, because emotional resources are a real thing that can be depleted—but to get to the point where you can maintain the boundaries and build the relationships so it doesn’t just take from you, it also gives to you. But at eighteen, you don’t know how to do that.

MOK: Well, most people. Certainly I didn’t. That’s a very mature thing for Ben to say, given that Ben and Otto’s relationship does grow codependent, and Otto is unaware of it, but he needs a lot of care. There’s not anybody else in his life that he can talk or connect with, and he’s going through a lot, like everyone there. And like you say, like a lot of people—I wouldn’t say a lot of young people, I would say just a lot of people—he doesn’t have any kind of knowledge about consent, and that is a huge strain on Ben, and probably on Otto, too. And that’s the tipping point in this one scene between Otto and Ben. Ben says, “Do you ever miss us being just friends? I wish we could go back to how things were before we were doing it, sometimes.” Otto freaks out and says, “I thought it was good for you.” Which in effect is saying, “You owe me, you owe me your body and your care.” And there’s a lot of rage from a lot of different characters, including a pivotal turning point, which is a bit of a spoiler, just so readers know. There’s this string of murders, where at the end you find out are all against teenage boys, committed by Empathy.

SUBURBIA: Empathy has a lot of rage that comes out in a lot of ways, whether it’s field hockey, or… whatever...

MOK: Are you going on the record saying that field hockey is more productive than murder? [laughs]

SUBURBIA: [laughs] I’m willing to stand behind that. I never played field hockey, but y’know… I think also, in this situation, she...

MOK: You also didn’t go on the record saying that you never killed anybody.

SUBURBIA: [laughs]

MOK: I’m just gonna call you on that.

SUBURBIA: [laughs] Damn. You’re too quick for me, Annie.

MOK: I know, it’s earlier in the morning there, it’s not fair.

SUBURBIA: What was I saying? Her pent-up feelings about this lack of parental guidance, the lack of boundaries or structure… She doesn’t have as much of an outlet to express her confusion. It’s easy, without anyone to stop you, sometimes you can get an idea in your head, like “I am a force for righteous vengeance in our community.” And if you don’t tell anybody, and if nobody says, “Mm, maybe that’s not a good idea,” it can take root. And the more she realized that she liked it, the more she reinforced the idea for herself that this is the right thing to do. It was empowering. It’s sick to get your feelings of power from killing people, but anything goes in this environment, so it took awhile for her to come around to that mode of thinking.

MOK: You’ve put her in a situation where it becomes clear that while you don’t condone what she does, I think I feel the same way about violence a lot of the time, where I don’t condone it but I don’t not condone it.

MOK: You’ve put her in a situation where it becomes clear that while you don’t condone what she does, I think I feel the same way about violence a lot of the time, where I don’t condone it but I don’t not condone it.

SUBURBIA: Sometimes it’s necessary.

MOK: Absolutely. I guess I can’t say that I don’t condone it... Where did that track of the story come from?

SUBURBIA: To be super honest, from prurience, and it became a little more layered as the story developed. I watched Battle Royale, and I liked the movie Jennifer’s Body, and Ginger Snaps, which are “teen girl becomes a monster and murders her male classmates” stories.

MOK: So just watching these movies and getting a thrill out of them?

SUBURBIA: Yeah, horror movies and exploitation films. There’s a trashy glamour to murderous young girls. So I put that in the story without thinking about it that much, and it developed from there.

MOK: There’s several scenes with horror movies, and several scenes influenced by the vocabulary of horror movies. I know you’ve mentioned to me that it’s a natural drawing thing that you tried and it stuck, but even just the way that the characters are drawn with these snake-like pupils, which are so distinctive and expressive. And then harkening back to Love & Rockets, with this wonderful magical realism, certain characters inexplicably have sharp ears or vampire-like incisors. Then there’s a scene with literal monsters. At one point they watch [Ginger Snaps], and the character says, “I get this ache, and I thought it was for sex, but it’s to tear everything to fucking pieces.” The theater burns down because they’re such idiots that they’re screwing around and they accidentally light grain alcohol on fire, just as this character is saying this line. Zombies come up over and over, too, in the story of a wasteland sort of town where this desolation is approaching. What do horror movies and zombie movies say to you?

SUBURBIA: I like them because they’re fun to read, there’s a lot you can dig into with the themes and the symbolism. A lot of times it’s there without the director or the writer even intending it. Sacred Heart, in an ideal world, if my artistic abilities were developed a little differently, would look a little more like a black and white horror movie, like the original Night of the Living Dead. I was thinking about that when I was economizing my drawing style. Big swaths of black trees as backdrop, and these characters seeming small in this darkness. A lot of my favorite horror movies are metaphors for adolescence, or that transition from childhood to adulthood. There’s that murderous female monstrousness from Jennifer’s Body or Ginger Snaps that comes in with Empathy, and then there’s the zombie thing, where they’re always sniping at each other for being complacent by waiting around for their parents. If you start watching horror movies when you’re a teenager, you’re getting scared but it’s fun for you, because it’s a way to frame what’s happening to you. It’s a fear that you can deal with because it’s so cut and dried. The Sacred Heart world reverses that, where the terror is in their real lives.

MOK: They’re in this horrific, chaotic situation, which is an extreme version of the “regular” things a lot of teenagers deal with, and then they find solace in these people dealing with totally chaotic situations. I think of the Evil Dead movies—it sounds like they’re watching a version of [Army of Darkness] at some point, because they’re talking about a zombie horse, and I love that they looked as solace to this character dealing in a comical way with a chaotic situation.

SUBURBIA: My favorite horror movies are the ones that have a little humor in them. I used to be way too scared to ever watch a zombie movie, and [Return of the Living Dead] was the first one where I sat down, and was like, “Okay, I’m gonna watch this one.” And the fact that it was funny and had some levity helped it go down a little easier.

MOK: There’s a tremendous sense of play with the drawings. I wanted to ask about figures, underdrawing, and process, and also about acting. In Sam Sharpe and Marnie Galloway’s podcast Image+Text, Sam said that acting is something that almost all cartoonists are terrible at, and I agree. Your characters have great range. Their gestures, expressions, and body language are quite subtle and say a lot. What’s your process like both for constructing figures, and for easing into your characters, figuring out gestures and expressions?

SUBURBIA: My pencils are pretty tight. I’m always trying to get them looser so that the final result is a little more spontaneous, but [laughs] it’s hard to let go of that kind of control. My thumbnails are loose, and I don’t spend a lot of time on them. I do a lot of my dialog on the fly, so a lot of it comes down to how much room I have for it. I’m terrible at balloon placement, I have no instincts for that kind of thing, so a lot of times I’m just trying to cram something around the character. And the focus is what the character looks like and what they’re doing… I don’t know. Maybe it’s more instinctual. I don’t think super consciously about what gesture they would do in the moment. I notice it when other comics don’t do it, and I’m like, “This is just talking heads,” but I don’t think about it much. I think it comes more from life, and like we said earlier, being a more observational person. Being sensitive to people’s facial cues, and the way people talk with their hands, and body language. ‘Cause if you feel like an outsider, you’re really watching that stuff extra closely, ‘cause you’re like, “How can I use this to make them like me?” [laughs]

MOK: I wanted to ask you about Otto. And also Jenna [frontwoman of the band Sex Heretic in the book]—is Jenna trans?

SUBURBIA: No, Jenna’s [cis] lesbian-identified. A lot of the gender and sexuality stuff is in the background because it’s kind of the long arm of the religious upbringing. Even without their parents around, there’s still the desire to keep it covert. Like Dominic, the boy that Ben has a crush on, him and his secret boyfriend still keep it under wraps, just in case, because their parents could come back any day.

MOK: Did you grow up in a religious community?

MOK: Did you grow up in a religious community?

SUBURBIA: We jumped from religious community to religious community. My dad is Catholic, so I went to a few Catholic schools, and I still have a lot of Catholic flavor. [laughs]

MOK: Everyone’s favorite! I grew up Catholic, too.

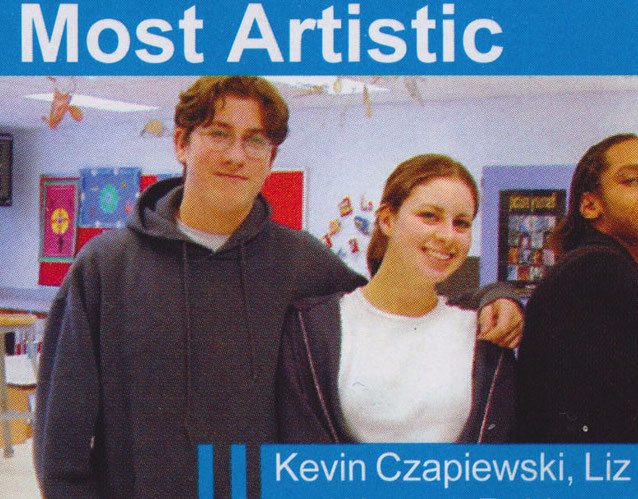

SUBURBIA: When I was five, my mom became born-again. My mom and dad got married and had me pretty quickly when they were overseas, and my mom got thrown into this army life that she wasn’t prepared for. She grew up in a small town. And moving every two years with three kids under the age of five is really, really stressful. She’s more chilled out now, but she got really into the Evangelical thing and clung to it for comfort when we were kids. I was going to Catholic mass, and Evangelical Baptist Pentecostal Sunday school and youth groups. I was very, very religious as a teenager. If you talk to [cartoonist and publisher] Kevin Czap, he remembers when I was like that.

MOK: You and Kevin have known each other since high school? That’s so cute!

SUBURBIA: I should show you the picture in the yearbook when we were both voted “most artistic” in our senior class… [laughs] So that’s the kind of environment they’re in. You asked if Jenna was trans; there is a stealth trans character. There didn’t seem to be any point in the story where it made sense to mention that about her.

MOK: Can I ask which person?

SUBURBIA: Donna, one of the two little girls who does the fake-ass Tarot readings and tries to predict the future.

MOK: Megan and Donna, who “prefer to be called ‘the Megadon.’” I love these characters who crop up as kind of a Greek chorus.

SUBURBIA: In the next book, I plan on opening with kind of a documentary on their whole situation. Donna feels conflicted because she’s raised by her cousin Candy, and she hurts for parental care like everyone else, but she also knows that if her parents had been around, they woulda made her wear boy’s clothes and use a boy’s name. She’s gonna carry those conflicted feelings around with her for the rest of her life. I have a separate story planned for her where she refines her spiritual or magical powers, and she goes on this quest to bring her friend back from the dead before she realizes that’s not a good idea, and makes her peace with it.

MOK: There’s also [gender] stuff going on with Otto. There’s this scene where Otto offers to take Ben to the dance, and he says he’ll dress up, too. Then [when Ben comes to get him] he shows up to the door in a prom dress and a cute flower barrette and makeup, and he’s like, “Pretty hilarious, huh!” And she’s like, “Yeah, uh, it’s nice, it’s a nice dress.” He quickly realizes that it’s not “Ha-ha, weird thing,” and it gets real for him very quickly. They go and get booze and ice cream, and Otto’s eating this crappy 7-11 ice cream cone, and smiling with lipstick on. And then that’s the moment when they hook up for real. They’re sitting next to each other [on the car hood], and Ben stares at his cleavage-ish poking out of his dress, and Ben kisses his shoulder. Then there’s this moment later in the story when they’re sort of breaking up. Otto’s sitting at home watching the end of the second Kill Bill, and he sees this vision of this male-assigned person in lingerie, and the person looks like him. Can you tell me about that scene?

MOK: There’s also [gender] stuff going on with Otto. There’s this scene where Otto offers to take Ben to the dance, and he says he’ll dress up, too. Then [when Ben comes to get him] he shows up to the door in a prom dress and a cute flower barrette and makeup, and he’s like, “Pretty hilarious, huh!” And she’s like, “Yeah, uh, it’s nice, it’s a nice dress.” He quickly realizes that it’s not “Ha-ha, weird thing,” and it gets real for him very quickly. They go and get booze and ice cream, and Otto’s eating this crappy 7-11 ice cream cone, and smiling with lipstick on. And then that’s the moment when they hook up for real. They’re sitting next to each other [on the car hood], and Ben stares at his cleavage-ish poking out of his dress, and Ben kisses his shoulder. Then there’s this moment later in the story when they’re sort of breaking up. Otto’s sitting at home watching the end of the second Kill Bill, and he sees this vision of this male-assigned person in lingerie, and the person looks like him. Can you tell me about that scene?

SUBURBIA: Well, some background on Otto’s gender identity first… Otto’s a character I identify with, and I put a lot of myself in. In the course of the story, we see him kind of cast a wide net as far as sexual and gender exploration goes, and doing some things that are kinda creepy, like hanging out under the bleachers to look at girls’ shoes and legs. He’s got something inside him that he doesn’t understand yet, which is something that I relate to. I’m assigned female at birth, and I’m married to a cis man, and we walk down the street and it looks… When you’re growing up in a religious environment and a narrow cisnormative and heteronormative world, you just think of yourself as the default even though the signs are all there. Like you said, that point of view shot from Ben, she thinks of herself as straight, but maybe she’s a little more queer than she realizes. None of these characters are aware of this stuff yet. They’ve all got bigger things on their mind. I guess this is a spoiler, that Otto survives the book.

MOK: Yes!

SUBURBIA: I didn’t conceive of him as a closeted trans woman, but I’m still thinking about where the character’s gonna go. He’s a fluid person, and I guess we’ll see how that solidifies as his life goes on.

MOK: “Closeted” is such insufficient language sometimes, right? In this case, and as was the case for me, it wasn’t so much that I was closeted growing up as I just did not realize what was going on. I never really had a period of being closeted, because as soon as I identified as trans, I told the people I was close to. The way that this vision of a person that looks like him appears to Otto, free of context and in a high stress moment, a moment of loss, mirrors my experience. It points out how nonverbal, how elemental and primal this experience is for Otto.

SUBURBIA: It goes back to the horror references, where it’s kind of a ghost moment: he sees this apparition. I’m very aware of the kind of privileges I have, as someone who’s female assigned at birth, who considers themselves gender neutral but doesn’t present in any kind of way that trips anybody’s alarms. So I wanna be really careful with the gender stuff in Sacred Heart.

MOK: Can I ask what pronouns you use?

SUBURBIA: “She,” “her.” It’s as good as any. [laughs] I use “she” for my dog, too. She probably feels as much like a girl as I do. It’s something I wanna treat sensitively. And I have a lot of fears about doing it wrong, because I come from such a place of privilege in relation to existing power structures. But it’s also really important to me not to pretend it doesn’t exist.

MOK: I get frustrated by the way a lot of people who think they’re being supportive treat trans women in stories, comics, and I also get frustrated with people who choose just to not depict them ever, very conveniently.

SUBURBIA: “All you have to do is listen,” that’s the tack I’m taking. There’s still that risk and fear, but I don’t think there’s an excuse not to address it, and not to try and learn. We’re living in the future here, and it’s easier than ever to stay intellectually curious, and be curious about the experience of others, and humanizing people who are not like yourself. Treating them like humans. It’s vital, otherwise you’re never gonna grow as a person, and you’re never gonna put good into the world. The education’s right there for the taking. I’m not articulating this well... It’s work that I’m glad to be able to do.

MOK: Are there things in that regard that you’d change about Sacred Heart now that you’re done with it?

SUBURBIA: I’m sure there are. I still feel like I haven’t separated myself from it all the way, now that it’s done.

MOK: Seems like you finished it pretty recently.

SUBURBIA: Yeah, in May. It was such a long process, and even with the editing and rewriting, there’s still changes to the story structure that coulda been made. I’m sure when I go back and read over it, especially with the more sensitive stuff, dealing with trauma and gender and sexuality, maybe I’ll look back on it and go, “Maybe I shouldn’t have put in so much nudity…”

MOK: I always think about writing characters that are teenagers, specifically in comics, is the issue of their boundaries. Particularly characters where I have a lot of privileges that they don’t, I often think about what would these characters be okay with me saying, given that they don’t exist. I try to think of characters having their own autonomy, and their own boundaries, in a way.

SUBURBIA: I tend to come down on the side of fiction giving you a little more flexibility with boundaries, but I also feel deeply that the moment the reader identifies with the character, that gives the character a little spark of humanity, and that’s something you gotta be respectful of. With the nudity and sexuality, I worked hard and intentionally to try to make it something that was humanizing. For the reader to identify with the characters, like, “They have sexual feelings, I have sexual feelings,” not “This sexy drawing is giving me sexual feelings.”

MOK: [The poet] Cat Fitzpatrick talked about sex scenes in movies as being, the story stops for a little while and they have sex, and then the story picks back up. That reminds me of what [the video game maker] merritt kopas had said about sex in video games, where in mainstream games, sex is the moment you put down the controller and stop playing, you stop engaging. How do you approach characterization in sex scenes?

MOK: [The poet] Cat Fitzpatrick talked about sex scenes in movies as being, the story stops for a little while and they have sex, and then the story picks back up. That reminds me of what [the video game maker] merritt kopas had said about sex in video games, where in mainstream games, sex is the moment you put down the controller and stop playing, you stop engaging. How do you approach characterization in sex scenes?

SUBURBIA: It was important to me to show that it was something that was happening. Even though, I’ll be real with you, I didn’t have any sex in high school. [laughs]

MOK: Neither did I!

SUBURBIA: Yeah. [laughs]

MOK: But people do! I remember walking down the hallway in-between periods, and seeing this blond girl say to this guy, “Hey, you wanna have sex this weekend?” And I was like, What?!

SUBURBIA: [laughs] Yeah, I remember my friend had been dating her boyfriend for a year and a half, an eternity in high school. We’d been friends for awhile and she casually mentioned having sex, and I was like, “You guys have sex?” If my parents hadn’t been around, who knows what woulda happened? So extrapolating from that, I was like, of course these characters would’ve been sexually active. With Ben and Otto, their relationship escalates quickly, even before she decides she doesn’t have the room in her life for their relationship as it stands, she’s like, “Do you think we have sex too much? Do you think it’s taking over our lives in an unhealthy way?” I tried to show that without making the sex itself seem like a bad thing. It’s something they’re both into and enjoying, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best thing for what’s going on in their lives and their relationship.

MOK: In Ben and Otto’s relationship, there’s a lot of care involved, and to a degree very nonconsensually. The sex is an element of that care. And like you suggest, sex takes a lot of emotional energy, particularly if you’re stressed out and if your life is fucked up. Even if it’s good and fun and something you wanna do, it’s not easy to integrate into your life, especially if you’re not used to it. That’s a point Ben makes to Otto a couple of times, and Otto really resists.

SUBURBIA: Otto finds out that he can be real with her in a way that he can’t with his guy friends, and he grabs onto her like a lifeboat. It’s a real need that he has, but at the same time it’s not something that she signed up for. I don’t want to judge him too much for having that need, but I also want to show that he’s not addressing that need in a healthy way.

MOK: As you probably know from comics, I started identifying as trans almost the same time as dealing with abuse in my past. It makes me think of the incredible degree that I had [around that time] that I was not conscious of on a verbal level necessarily, for my relationships, both friend relationships and especially romantic relationships. I see that in Otto. He brings this gender exploration to Ben before he does to anyone else, and it’s kind of private. I see that as part of the strain that’s making this extreme need, not being able to deal with what’s going on with himself.

SUBURBIA: Yeah, and only being semi-conscious of it. I definitely can feel that confusion writing it.

MOK: What do you make of some of the magical elements? There’s the scene near the end where Ben gets stigmata. For them, growing up in a religious community—it’s one thing when there’s monsters, but it’s another thing when Ben has this horrible religious experience that’s almost demonic.

SUBURBIA: There’s a lot of Catholic flavor to the story. She starts the first stigmata on her side in the school bathroom, earlier, then it comes back.

MOK: Then of course, the ending with the flood, this massive Biblical torrent.

SUBURBIA: It’s all mashed together in my head. I have trouble separating that stuff from the rest of existence. There’s a lot of it in Love & Rockets. I read a lot of Hellboy too, there’s a lot of Catholicism mixed with other stuff going through there. It made sense to put it in my comic.

MOK: The Bible is certainly science fiction.

SUBURBIA: [laughs] It’s pretty wild.

MOK: I noticed as soon as I started writing songs in [See-Through Girls], Catholicism hadn’t come out in other forms of art, but with songs I was writing about plagues of locusts, blood above doors. I guess there’s something about music to me that’s religious-connected, because pop music is so grand. There’s a wonderful sense of play connected to music and other elements [in Sacred Heart]. You visualize music as little disparate clouds that are directional, that suggest sound pulling out of the instruments or the voice and dissipating over a crowd. In the scene where Jenna plays for the first time, and everyone’s giving her shit for being a fat girl in a band, she starts playing and [the audience’s] faces literally rip off and reveal their skulls. A lot of “serious” graphic novels are extremely staid. Sam Sharpe referred to his own comics as “I’m still making mini-movies,” and I see that in a lot of graphic novels: a lack of play in regards to the drawing. In your book, there’s a riotousness in some of the formal elements. There’s that “Doggie Break” part where the chapter’s from the dog’s point of view. There’s the scene where the guys are walking, and there’s a panel of a close-up of their heads and a panel beneath them of close-up of their feet, and [the two panels together make it] look like they’re in a fun house mirror. Can you talk about that sense of play?

SUBURBIA: Comics just make it so easy. You can draw anything you want. When I worked at the comic shop, I heard people complaining a lot about this one artist on Spider-Man. Spider-Man’s got these white, blank eyes on his costume. This one artist would draw them as squinty, even though they’re part of the costume, so they wouldn’t be able to move. I remember that from the opening credits of Batman: The Animated Series, where he’s in silhouette and you see his eyes narrow, even though those are just the holes in the costume, so you couldn’t do that. It’s a comic! You can do whatever you want. You don’t have to obey the laws of physics. I watch a lot of movies, a lot of TV, I have that love affair with movies that a lot of people of our generation do. But comics is like a movie you can make for almost no money, and you can do whatever you want. You’ve got the budget to do whatever special effects are cool or fun for you. With the music especially, I came up with that shorthand to denote noise because that’s the thing that comics don’t have, is sound. I’ve heard [cartoonist] Brandon Graham complain about music in comics: “I can’t hear it, there’s no point!” If I see just lyrics and no effort… “Here’s the band, and here’s the words that they’re singing.” I have no musical ability, I can’t even carry a tune. I can’t imagine music to go with these words. It comes across awkward a lot of times. There’s some people who can really communicate it. I remember a scene in the most recent book of Wet Moon by Sophie Campbell, where it’s lyrics and a character singing them, but she managed, through the shape of the word balloons, and the dynamic panel construction, it comes across. You can’t show the music, but you can show how it makes the characters feel, and how it’s changing the atmosphere and the environment.