Jillian Tamaki’s new book, Boundless, has just come out from Drawn & Quarterly. It’s a collection of her short comics done over several years: a calm, whipping, crackling body of work.

Jillian Tamaki’s new book, Boundless, has just come out from Drawn & Quarterly. It’s a collection of her short comics done over several years: a calm, whipping, crackling body of work.

To talk about Jillian Tamaki’s artwork, for me, means talking about myself. For most of my life I felt like being a woman meant I was worth less as a human being. I felt like I could never make art as good as I could have if I were a man.

I first learned about Jillian Tamaki’s work around 2007. After several years of seeing the images she created, I knew that there was no artist who was better than her. There are artists who may be as good, but there is no one who is better. It was the first time – but not the last - that I was able to recognize this in a woman artist.

After that, a long and awful lie broke apart inside me and began to melt away.

– Eleanor Davis, May 17th, 2017.

ED: What story of yours have you found people respond to the most strongly? And what was your response to their response?

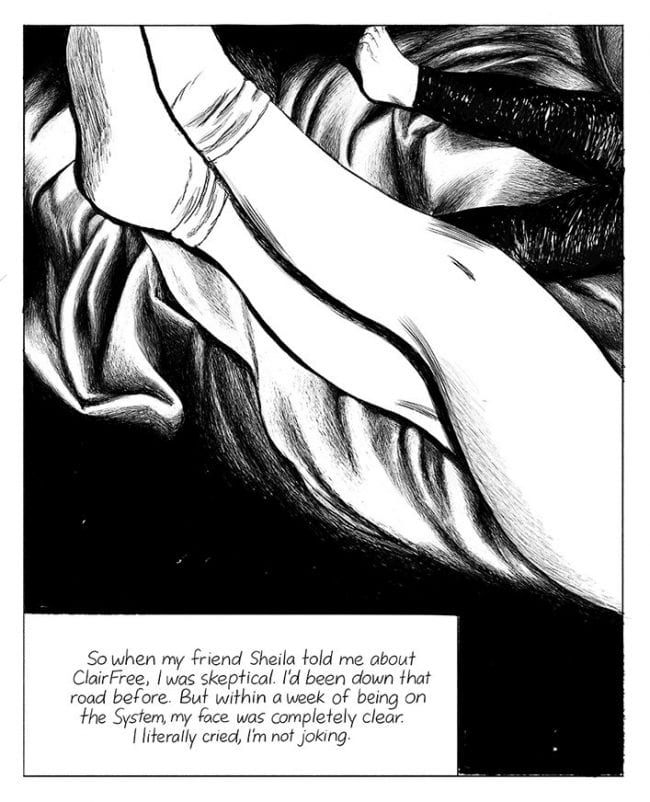

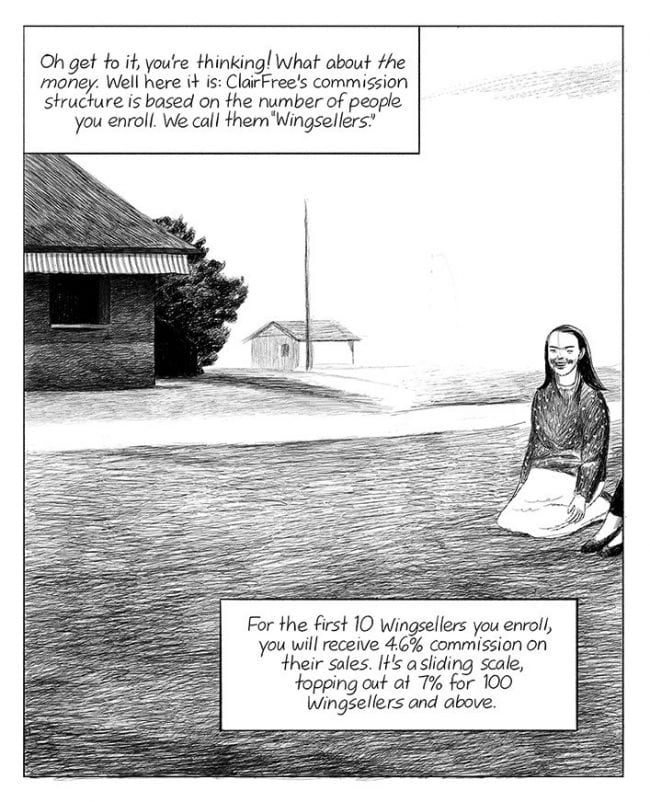

JT: Well, obviously the strongest reaction I have had to A Book has been This One Summer, which is a collaboration. [This One Summer, by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, was the ALA’s most challenged book of 2016 – ED]. It's interesting, for the interviews for Boundless thus far, people have wanted to discuss “The ClairFree System.” Which is slightly surprising.

ED: I experience the clearest emotional arc reading it. Not intellectual clarity, but emotional, with the conditional intimacy of the final moment.

JT: I'm trying to think of their "reaction" though. I feel like they want to hear me talk about it. It feels very mysterious and strange to them, I guess? It's not a typical image-text pairing. I mean, it's about The Economy, which I think about constantly.

ED: I read that comic as both a feminist critique, and defense, of Capitalism. I LOVED it, obviously.

JT: I had forgotten: that story was sparked by learning that some of my friends in my hometown had gotten into what they called a "Skin cult." Which is maybe a pyramid scheme? You made commissions off of selling to your friends. But on the other hand, it just seemed like Mary Kay or Avon for the millennial set. And it was bizarre because I was like, oh, I remember Avon and these suburban selling-parties when I was a kid. But now I'm on the flip, the adult, and the moms needed CASH.

ED: It's so fucking empathetic to the need for both beauty - a healthy, smooth exterior - and money. It’s so empathetic to what those two things can mean, in this case for women.

ED: It's so fucking empathetic to the need for both beauty - a healthy, smooth exterior - and money. It’s so empathetic to what those two things can mean, in this case for women.

JT: I am constantly bewildered by the juxtapositions of city-life. Like, businesses closing left, right, and center, but then so many empty storefronts. No one can afford to rent, and yet we can bid $500K over asking price on teardowns. So there was an attempt at that in that story. Human needs and desires with cold hard, figures. Friendship and manipulation. Hopes and realities.

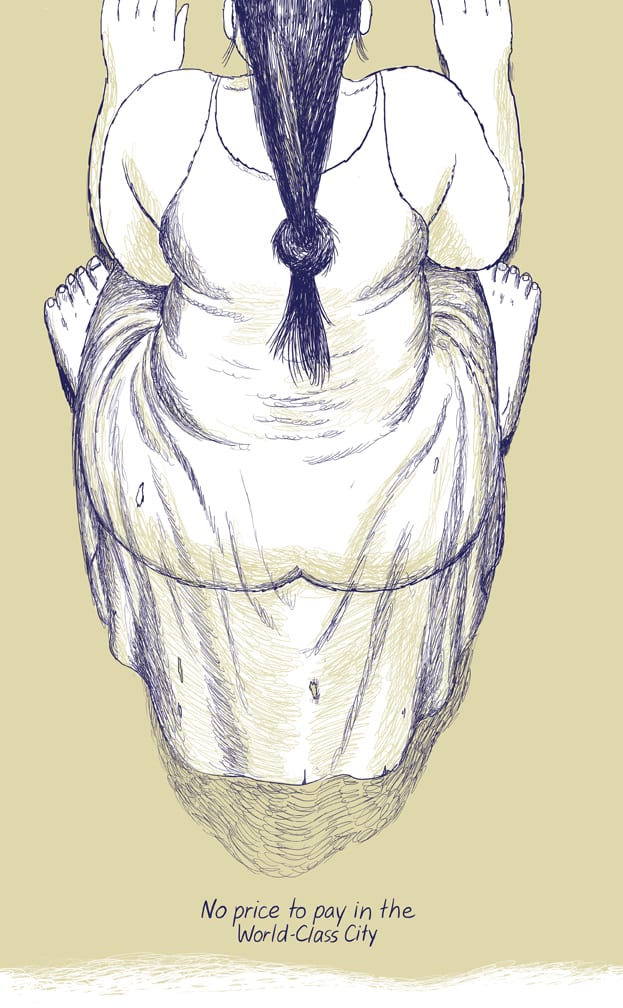

ED: I've noticed you think about environment a lot. Your first comic in Boundless, “World Class City,” is one of my favorites. That comic is so loving, and scared, and hopeful, and sheepish? I don't know if I'm projecting too much.

ED: I've noticed you think about environment a lot. Your first comic in Boundless, “World Class City,” is one of my favorites. That comic is so loving, and scared, and hopeful, and sheepish? I don't know if I'm projecting too much.

JT: Cities. I feel like it's a real relationship. With longing and dreams and disappointments. Beautiful bits and really ugly bits. That comic is about NY, but can be about any big city. People project so much onto NY, it is still seen as a place to go make your dreams come true, put yourself to the test, be the best version of yourself, possibly even make yourself over. I think this thing can happen where the city gets folded into your identity. It's a song, by the way! The words in “World Class City” are song lyrics

ED: Oh! Like, an existing song?

JT: No! The one and only song I have ever written. I was briefly in a punk band with a few other women in their 30s.

ED: Oh my God! Your band Shebola? Have you recorded it? Why doesn't Boundless come with a flexidisk insert?

JT: It always ended up very shoegaze-y or angry songs about pussies. Literally, we could have put out an album of pussy songs. Anne Ishii and Chelsea Cardinal are the other members.

ED: FLEXIDISK INSERT!

JT: Oh God, I would like to be much better! I am very enthusiastic, though. Screaming is great.

ED: Jillian! That's so cool! I want to hear this song‼

JT: This is so embarrassing, but here is “World Class City,” the song, sort of.

[JT sends ED the song]

[ED listens to the song]

ED: Holy shit! I love this so much! What instrument are you playing? This is just hugely satisfying.

JT: We switched all the time! Guitar, keyboard, drums. Punk as fuck.

ED: Did you write “World Class City” after you realized you were gonna leave New York?

JT: Oh yes. Definitely. I had always had a very weird, uncomfortable relationship with New York, but it was my home and leaving was very melancholy despite being 100% the right decision.

ED: I read it in the voice of someone who is in love with a thing, but is aware of being in denial about its flaws. A keening sort of mournful love.

JT: Oh, I never fell in love with the place. But, I'm glad. I prefer that, instead of it seeming sarcastic.

ED: How did you decide the images for it?

JT: To be honest, I can feel increasingly confined by the image part of comics. Perhaps because often, for more commercial works, the images need be a lot more literal? I feel like images can "lock" an idea. To depict someone specific can be nice sometimes - the books I do with Mariko are always about specificity of time and place and character. But sometimes it's nice, when reading prose, to have the ideas and concepts more open. They can feel more universal or possibly even symbolic. So I guess this comic was about trying to stretch that word-image relationship. I don't want to show you what kind of person thinks this way, acts this way, etc.

ED: “World Class City,” and another story in Boundless, “The ClairFree System,” are doing an odd trick that I'm not super familiar with in comics. With both of them the divide between the words and the images is very stark. The dreaminess of the images makes real life feel muffled. Then, in “ClairFree,” when you come out of the beautiful dreamlike images and into a sequence depicting reality, reality is this scruffy, itchy thing.

JT: The images in ClairFree system are a combination of found photos I had kicking around and pictures I took of various artworks at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Both were sort of adapted to a sort of universality, which is what that comic ends up being about.

ED: It feels hypnotic.

JT: Most of the artworks were statuary. Universality is the wrong word. Perhaps more like, the line between hope and survival, future and present?

ED: The images have a sense of purity and solidity, and grandeur.

ED: The images have a sense of purity and solidity, and grandeur.

JT: I dunno, I just feel like, how to recapture some of the feeling of prose? Where ideas are so much more free-floating. It's cool to create juxtaposition between dialogue and body language, I do that all the time, and we have our tricks as to how to create ambiguity, but what if you are given NO "clues" as to how the words are intended? Sometimes comics can feel like seeding clues.

ED: Yes! I think you did that!

JT: Ideas, dialogue, environment.

ED: One of the things that makes me feel crazy about comics is that they're so distant, inherently.

JT: How so?

ED: Prose feels like it's happening inside your head, because you're building the images of the text yourself. Comics does that work for you, about fourteen inches in front of your face, so you're less engaged. With “ClairFree” and “World-Class,” you're allowing the world-creating prose-response, but then folding additional images on top of that. I had a sense that both comics existed inside my own mind in a way that other comics do not.

JT: Perhaps some people will feel the image-word relationship will have been stretched too far.

ED: Yeah, dude, it's going to really bug a lot of people!

JT: Well, whatever [Laughs].

ED: Just to give you a heads-up. [Laughs] I know this is kind of a shitty attitude, but I feel so comfy in people not getting my stuff. I just roll around in it.

JT: I wonder if having a kid would change this equation entirely. If you're suddenly all, ok, cool, time to flesh out the SuperMutant Magic Academy universe and call up Cartoon Network. Instead at this point it’s like, what am I going to do... NOT try to push myself? I've been making some choices that are, "ok, well, you're in a position to do this."

ED: I've been there lately too. It feels good, and bad, and scary.

ED: I've been there lately too. It feels good, and bad, and scary.

JT: It's really scary. I don't think we're supposed to talk about being scared.

ED: Yeah.

JT: Mid-career is a trip, man. I have seen so many ppl around me flip that switch, where it's like, "time to get real."

ED: Time to get real, like, make that money?

JT: Yeah, or the innovation stops.

ED: "This look is selling."

JT: This sounds weird but it can almost seem childish or selfish to keep on pushing in this way.

ED: Well, art directors and audiences don't tend to ask for it. It IS for oneself.

JT: Yeah. It's true. Feels increasingly like a choice.

ED: I am trying to think of anyone I know who has pushed their style so much or as successfully as you have.

JT: What choice do I have but to try to aim for the highest heights? I simultaneously HATE this way of thinking, because it strikes me as so masculine, and phallic and horrible.

ED: Don't you think we're both masculine ladies though, in that regard? I am OK with that. When I'm not being my best self I'm proud of it. Wanting to succeed, fuck it, that's my feminist act of resistance.

JT: I'm really lucky though. It does feel like a very charmed life.

ED: Oh my God, I say I'm lucky all the time but I HATE hearing you say you're lucky! Guys don't say they're lucky!! They say they WON!!!

JT: I work hard but.... right time, right place, etc. etc... THAT kind of luck! Like, COSMIC luck!

ED: Jillian, that's what I say! But it’s infuriating to hear you say it! It's LUCKY that God came down and pressed his finger into your nog and gave you fight mixed with skill!

JT: WELL! I mean! I coulda had shitty parents who forbade me from drawing and forced me to be an accountant like my dad!

ED: OK, that part is "lucky." That part was lucky for all of us. [Laughs]

Final question: what do you think an artist owes their audience?

JT: I accept various answers. If someone were to respond, "NOTHING!", I totally accept that! I'm even OK with a level of cynicism from an artist. I guess for me I have found the most powerful and meaningful outcomes have arisen from people connecting with characters or stories, and relating them to their own lives or situations. I feel I owe my audience honesty so we can make that connection.