Jeet Heer is one of a small group of writers and critics about comics who have been enrichening the discussion of comics in the 21st Century. A regular contributor to TCJ, Heer is the author of In Love with Art, about Francoise Mouly, and has co-edited books including Arguing Comics, A Comics Studies Reader, and The Superhero Reader. He’s also written introductions to many collections of comics including Little Orphan Annie, published by The Library of American Comics/IDW.

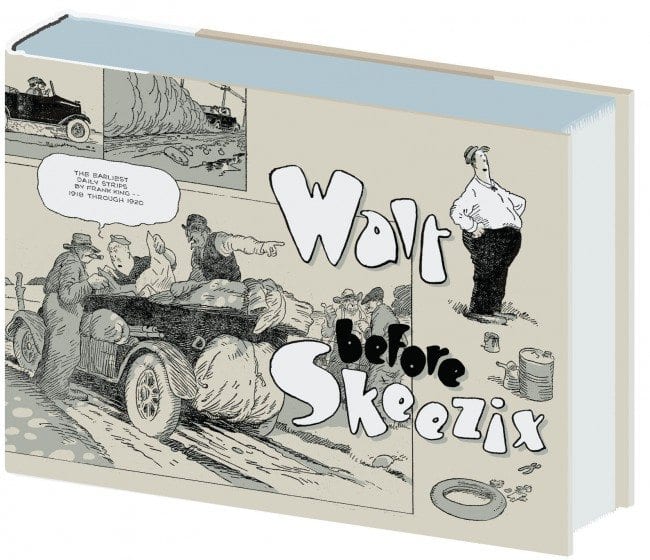

In addition, Heer is the co-editor of the Walt and Skeezix books from Drawn & Quarterly. These collections of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley have been one of the great comics publications of the past decade and have led to a new appreciation for King and the strip. The newest volume in the series is Walt Before Skeezix, which collects the early years of the strip. It’s clear reading the strip why they didn’t start reprinting the series with these strips, as they are so different from what will follow, but it’s easy to see how, King grew as a writer within a few months, and glimpse the shape of the masterpiece that he would go on to create.

Alex Dueben: I’m glad we could talk about Walt Before Skeezix and your other projects. There’s a lot to talk about.

Jeet Heer: I’m heartened you wanted to ask about the Walt Before Skeezix book because when we were working on it, I thought it was going to be a hard sell, since it doesn’t have the narrative of the other series. It’s 100-year-old jokes about cars. [laughs] We thought we’ll do this and then resume the books everyone loves but oddly enough Walt Before Skeezix has gotten more attention than any book since the first book in the series. The first book gets a lot of press and acclaim but as so often happens with continued series that tapered off quickly since people assumed each new volume was just more of the same. Walt Before Skeezix has gotten more reviews and more praise than anything in the series for a while.

This is technically the sixth book in the Gasoline Alley reprint series. Why was this the time to go back and do these early strips?

We had several reasons. One is that we had just completed a decade of the Gasoline Alley series. We’d covered the twenties, and we’re going to do the thirties but we’re probably going to redesign the series a little bit to give it a different feel for the new decade. In between the redesign we figured now we can go back and do the beginning strips. Maybe another way to say this is why didn’t we start with these strips because we started in 1921 instead of 1918. The reason is that the appeal of the Gasoline Alley strips is the relationship between Walt and Skeezix. That’s why we call the series Walt and Skeezix and we wanted to start with Walt discovering Skeezix and then the baby ages in real time. But we always wanted to reproduce the early strips at some point so it seemed like a good time to do it.

You talk about this a little in your introduction to the book, but all the things that became evident a year later you can see in the strip emerging in 1920 before Skeezix arrived.

Now that people are familiar with King’s work, from having five volumes of the dailies and some other volumes reprinting the Sundays, we can go back. In some ways readers are in a better position to understand how Frank King evolved because we know what he ended up. We can go back to the beginning and see him putting things together. I really see part of the interest in Walt Before Skeezix is you can see an artist evolving and almost brick-by-brick building this series. In some ways it has the interest of early Peanuts where it’s not quite the Peanuts we know and we see Schulz trying out different characters and different ideas and really working at the parameters of what he’s doing. I think that alt Before Skeezix definitely gives you that. You see different directions that the strip could have gone into. The times where he’s really highlighting the character Avery and his wife and the strip could have focused on the penny-pinching Avery and his wife. Then Bill and his wife Amy have a child and you can say that if he hadn’t decided to have Walt discover Skeezix, it could have been a family strip about Bill and Amy.

One reason I specifically wanted to talk with you about the books is that if the canon of comics has changed in the past fifteen to twenty years, I think it’s the addition of Frank King and that’s because of these books. It’s a reprint project but it’s also a scholarly and critical project.

I think that’s definitely the case. One of the things we had wanted to do is to get people to take a second look at Frank King and the books do a heavy contextualization of him. I’ve written about this on several occasions, but what’s also happened is that as a new wave of alternative cartoonists have come around we can see Frank King as being part of a larger story. Chris Ware doing work like Jimmy Corrigan and Building Stories—Frank King becomes the ancestor of that. Not just Chris, but Kevin Huizenga and Sammy Harkham can now be seen as the grandkids of Frank King. And there’s a whole school of cartooning that we can now see Frank King being one of the initiators of. It sounds like boasting but I do think that the series has done more to change the comics canon than most books of this sort have. I think people have a much higher opinion of Frank King now than they would have in the 1990s or 1970s.

I spoke with Jules Feiffer a little while back and he mentioned his love of Gasoline Alley, which he didn’t love when he was young because he couldn’t see what King was doing, but he’s able to in the books.

I think that’s true as well. I think that in some ways the emergence of the graphic novel as a genre has given us a new way to read Frank King because we can now see him as being a novelist in comic strip form that follows the life of a character. Gasoline Alley now reads not like a daily comic strip but as a multi-volume roman-fleuve. For a lot of readers in the twenties if you were reading it day by day you don’t necessarily pick up on that. I’m very gratified by Jules Feiffer’s remark. I think that in some ways the strips work better as a graphic novel than they did as a daily strip. It was a popular strip and a lot of people loved it at the time, but now that you have it in book form we can really see the grand scope of King’s work. We’re living in the age of the graphic novel and there are people reading graphic novels. That also changes the way we read Gasoline Alley.

I reread Walt Before Skeezix because there’s a point where it stops being a gag a day strip and King has each strip represent a day in the life of these characters.

In some ways I think it’s part of the move from the panel the square panel to the sequential strip. That introduces an element of narrative and character evolution. Also I think the addition of the baby, as well, even before Skeezix is born we have the pregnancy of Amy. This is at a time when you don’t have comic strip characters being pregnant. It doesn’t say it explicitly but if you read carefully you know what’s going on. You’re seeing a 1920 view of what pregnancy and childbirth were like.

How did you first get involved in this project?

Drawn & Quarterly had this yearly anthology in book form and they had reprinted fifty pages of the color strips along with Chris Ware doing the cover of the book doing an homage to Frank King. I reviewed that for the National Post where I was doing other writing on comics. Through that Chris Oliveros became aware of my work and I met Chris Ware when he was on tour for Jimmy Corrigan. We knew each other and hit it off so when the time came to do the book it all came together.

There’s an earlier pre-history of all this where a big figure is Bill Blackbeard who in the 1970s had co-edited The Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. That book was very influential in reviving Frank King because it included six of the Sunday strips, very well selected and reproduced, which was not common in 1970s books. Chris Ware, Joe Matt, and I all read the Smithsonian book growing up and those six pages really sparked in all of us an interest in Frank King. Joe Matt is the real unsung hero of this. He started collecting Frank King dailies and Sundays and amassed a huge collection. Chris Ware had his own collection. I know that Bill Blackbeard died a few years ago but I always want to mention his name because he really planted the seeds that made the Walt and Skeezix books possible. Not just those books, but the whole age of reprinting comics that we’re going through is really a product of Bill Blackbeard.

What was the thinking behind collecting the daily strips but not the Sundays?

That’s Chris Ware’s intervention. When we first started doing it I thought we were going to do the Sundays. Chris and Joe Matt were more aware of the dailies than I was and those guys had an understanding that King’s genius was in the dailies, in the accumulation of stories and having the characters age in real time. That was something I was only vaguely cognizant of, but thanks to Chris and Joe we made the right decision.

I know there are collections of the Sunday strips elsewhere.

There’s actually been a couple of collections since then. Pete Maresca did a great book and now Dark Horse is doing a series of the Complete Sundays. Everything is getting reprinted. There’s actually four different publishers that have put out Gasoline Alley books in the last decade, which is great. It’s a huge body of work.

It is a huge project. When you signed on were you thinking okay we’ll publish the entire fifty years that King worked on the book in twenty-something volumes over however many years?

I don’t think we’ve decided yet how far we’re going to go. We want to get as much of King’s work as possible. He takes on assistants at a certain point so it becomes less and less his own work. I don’t want to speak for Drawn & Quarterly because we haven’t decided but I feel like going to the end of World War II would be a good end point. After that King is using assistants a lot and the strip takes on a different feel. To get Skeezix from being born to serving in the war and returning home – that feels like a natural progression. He marries before the war and has a son after the war. That would give you a good sense of his life. That’s a good end point. But nothing is set yet. We’re going to do as much as we can.

It’s a large project, but in some ways, the way we’re doing it gives it the feel of the strip. People are following it from year to year. It reproduces some of the effect of a being a comic strip you live with.

Speaking of larger projects, you’re writing essays for the reprints of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie.

Speaking of larger projects, you’re writing essays for the reprints of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie.

Yes and that’s about the same length–44 years–and that’s going at a good clip too. I don’t think every comic strip needs to be reprinted completely. I think there’s a lot of comic strips where a “best of” approach would work well. There are a few like Krazy Kat, Peanuts, Gasoline Alley, Little Orphan Annie, where you need to get the full sweep of it. You see the cartoonist evolving and changing and reacting to the world around them. It makes for a very rich reading experience.

You interviewed Walter Biggins the other year and touched on this idea about how we’re starting to see comics programs and academics who write about comics

It’s definitely proliferated far beyond what anyone could have predicted ten-fifteen years ago. Comics Studies is a very lively part of academia now. It used to be that University Press of Mississippi was the only one but now there are other presses–Rutgers, Ohio State, Yale University Press–that have substantial lines on comics. That’s all to the good. It’s very interesting because what you also see is a lot of comics scholars who are involved in comics culture and there’s a cross fertilization. I was invited to Denver Comic Con to give presentations with other academics. I think that’s interesting that in comics culture you have academics who go to comic cons and there’s an overlap. There’s an academic event that’s affiliated with TCAF. You don’t see that in other areas. You don’t see academics at the Cannes film festival or the Toronto film festival and giving panels as academics.

I’m interested in two things related to that. One, what is the role of independent scholar in the midst of this?

I think independent scholars are very important and there’s a couple of them who have been really crucial. One is R.C. Harvey who did a couple books with Mississippi and writes for The Comic Journal. He’s someone who doesn’t have a scholarly position but does a lot of really valuable writing. I think that’s a crucial part of the story, especially in the early days. I mentioned Bill Blackbeard before and I think he’s a classic example. He saw value in something other people didn’t which is these old newspaper strips and he was an independent collector. Now eventually his everything that he gathered these trailer trucks full of newspaper comics have been bought up by Ohio State University. Independent scholars are a crucial part of comics scholarship being built up.

I interviewed Katherine Roeder recently about her book on Winsor McCay and we talked about how most comics scholarship comes out of English departments.

Her book is very valuable. I had read her thesis before it was a book. I think that’s one of the other things that’s happening. In the early days of comics studies a lot of it was coming out of English so there was a heavy emphasis on narrative with a real interest in people like Alan Moore, who does a lot of stuff that English scholars would be familiar with in terms of creating complicated narratives with a lot of symbols and textual interplay. But comics are also a visual form. There are a few people like David Kunzle, who did a valuable history of comics, but it’s very rare for someone in art history to do comics. That’s something we’ll probably see more of. It’s a valuable perspective we need.

That parallels the popular conversation about comics in thinking of it as a writer-driven medium and thinking about it primarily in terms of narrative rather than art

I think that’s true. Again to talk about independent scholars it’s coming from people like Dan Nadel and Frank Santoro. That’s the other thing in terms of independent scholars a lot of the best or most interesting comics theorization is coming from cartoonists themselves. Because the academy was so slow to take it up, people like Will Eisner, Art Spiegelman, Scott McCloud, Lynda Barry have been major theoreticians of what comics are and how they work.

Frank Santoro recently wrote that how he wouldn’t read criticism by people who don’t make comics.

I don’t agree with Frank on that point but I think Tim Hodler’s point [in The Comics Journal] was pretty much on target, which is that people use criticism for different reasons and Frank is using criticism as a particular type of educator. He’s running a school for cartoonists so he wants cartoonists to be thinking in terms of practice. For him a lot of the more theoretical more academic more historical writing isn’t really pertinent to teaching someone how to make a comic. I think that’s where Frank’s comment comes out of. A specific type of pedagogy that he’s trying to follow through.

I think that's true, but comics are probably one of the few media where you could say that and still have a significant body of work to work from.

I think that’s true. In the olden days you did tend to see filmmaker-theoreticians. Hitchcock/Truffaut is the great example.

Late last year your monograph In Love with Art about Francoise Mouly was published. I can’t help but think about how some of what we’ve been talking about, the thinking about comics from a narrative perspective, means that people like Mouly are ignored.

I think that’s right. That’s part of what I wanted to get across in the book. It’s hard for people to see what she does because so much of what she does is in the world of design and visual editing like giving artists advice how to tweak a cover or tweak an image. A lot of the sensibility she brought to that partnership was a visual sensibility. Look at the difference between Arcade, which Spiegelman and Bill Griffith created, and RAW. In RAW you see a much more visual sensibility and I do credit Francoise with being a big part of that change. In writing about Mouly I wanted to highlight comics as a visual medium. I’m glad you picked up on that. I think that’ a very important point and it also helps to explain one of the central points of the book which is why her contribution has been ignored.

Also in general editors tend to be ignored unless they’re someone like Gordon Lish where their sensibility is prominent, which is its own problem.

Yeah. It’s interesting in comics as well because there hasn’t been a lot of great editing but there’s been a lot of dubious editing. Harvey Kurtzman was undoubtedly a great editor. After him, we have Spiegelman and Mouly but other than that what do we have? Mort Weisinger, whose idea of editing is to say, “Let’s put a gorilla on the cover.” There’s Stan Lee who takes credit for what Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko have done. That’s not a great tradition of editing. There’s Jim Shooter who fired Gene Colan because he didn’t match Shooter’s idea of what Marvel Comics should be. [laughs] Maybe I’m being unfair. Another predecessor would be newspaper people like William Randolph Hearst sticking with Herriman in his period of unpopularity. There are some good editors.

There are some good editors, particularly in the past twenty-thirty years, like Diana Schutz and Bob Schreck and others. Archie Goodwin is probably the model of a great editor in comics.

Those are all good names. There are plenty of good editors: the late Kim Thompson, Gary Groth, Eric Reynolds, Chris Oliveros, Tom Devlin, Annie Koyama, and Dan Nadel. There’s a curatorial sensibility in editing which we really see in the art side of comics.

That stands out because you don’t see that curatorial sense in mainstream comics where the editor’s task is to put out x number of books a month with y number of pages.

One thing with Mouly which we see going forward with Drawn & Quarterly and others is the idea of you don’t just grow for the sake of growing. They could have published 50 to 100 titles under the Raw label and they decided, no, we’re going to do this out of our loft and select the artists and do one or two books a year. I think that’s very important to have a model where your line fits together because you’ve selected them very carefully.

You wrote a good piece for The New Republic earlier this year about Herblock and your point was that he was an interesting and important artist, but the film deified him.

I had to write that very quickly so I didn’t get to go into all the details, but in some ways it does him a disservice by deifying him because it makes him this bipartisan figure. In this way of thinking, Herblock stands for America and all these patriotic principles almost everyone agrees to. I think one of the interesting things about Herblock is he is a real partisan. When he hated someone like McCarthy or Nixon, he was a dirty fighter–which is good! To make Herblock into the Statue of Liberty is to do him a disservice. I don’t write a lot about political cartooning because I find it a hard form to write about. A lot of it dates very quickly and it’s hard to get at but it’s something I’m trying to think about writing about political cartoonists because some of them are very important and some of them I really enjoy like Matt Bors or Ruben Bolling. There are people doing interesting work but I find it hard to write about them because the nature of their medium is such you don’t have a plot or character to hang your hat on.

I bring it up in part because I think that’s a trap a lot of people fall into when writing about cartoonists.

I think that’s right. There is a tendency to deify and I try to resist that as much as I can even with figures I have a lot of respect for. I have a lot of respect for Herblock, I just don’t think we should deify him. I think you want to try to get at the complexity of these figures as much as you can and in some ways you see that with the opposite with someone like Harold Gray. It’s easy for people to dismiss him as this fascist warmonger. Warbucks is his hero–“War bucks.” But if you go into the weeds and Gray is a very complex, interesting guy. He’s much more friendly towards immigrants and towards racial minorities like Chinese Americans and Jewish Americans than any other cartoonist of his age except maybe Milt Gross. Harold Gray and Milt Gross are the two cartoonists who have an appreciative sense of the diversity of America and you don’t expect that from Harold Gray. With Gray I want to say, let’s step back and not just call him a fascist but see what’s going on in his work. You want to get at the complexity of these figures.

Whenever people tackle something like Li’l Abner, there’s the question of, how do you treat Al Capp?

I haven’t written about Al Capp because I would find it hard to balance my appreciation for his work with my distaste for his personality. I enjoy late 1940s Li’l Abner and I love Fearless Fosdick, but Capp is in a lot of ways a very unsympathetic human figure. One way to think about him is that comics culture has a larger problem with gender and the persistent harassment of women. This way we can see Capp as not an anomaly but as more typical of the culture than one would like to think. It would be an interesting project to do a human portrait of Al Capp because in a lot of ways he’s such a monstrous figure. I think I would find it hard to go back and reread Li’l Abner knowing everything I know about Capp.

I haven’t been able to read Li’l Abner since reading the Denis Kitchen-Michael Schumacher biography of Capp.

Yeah it’s a hard thing. Humor relies on some sort of shared sympathy. You’re making a joke together. It’s different than if someone is a poet or doing work that’s not trying to be funny–like Ezra Pound. Pound was a monster on many levels yet his poetry still yields riches, but with humorists, you want to feel a human connection to them. With Al Capp, it’s genuinely hard after you know about his life to go back and appreciate the work. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

That’s often a problem with biography. I know the Schulz family wasn’t thrilled by the biography of him, but it is a struggle to convey the complexity of these figures without destroying the work.

It’s more of a problem with Capp than Schulz. Even at his most horrible moment, Schulz is still an endearing human being. I had problems with the Schulz biography as well, but I thought it was okay. I can still appreciate Schulz and I don’t think it did any lasting damage to Schulz, but gave us a more complex view of the man.

I know that you write about a lot more than comics, but what else are you interested in doing, going forward?

I do a lot of writing on literature and culture in general and politics. I’m putting together a new collection, Sweet Lechery, which will collect the range of my essays. There will be a lot of stuff on literature, some stuff on politics and a few pieces on comics and science fiction. In the future I do want to do more monographs on the model of In Love with Art. I have a list of artists I want to do book length studies of. It’s just a matter of finding a publisher and the right circumstances.