In 1987, at the tail end of his undergraduate art studies, Chris Byrne began a comic strip called The Magician. He returned to it in 2000. But then it developed into something else, only just finished in January 2013: 12 objects housed in, and dependent on, a facsimile of a magician’s box.

In the intervening years Byrne ran a gallery in Dallas, became an art consultant and curator (including his collaboration with Gary Panter on a Zap retrospective in 2011) and co-founded the Dallas Art Fair in 2009. He became very interested in Peter Saul and spent years selling and researching the older artist’s work, culminating in a primary involvement in Saul’s 1999 Paris retrospective. He learned something important from Saul, which was “to let the imagery go where it goes, as opposed to the materials-first approach of most modern and contemporary painting”. And like Saul, everything in his life could come alive and find its way into the project.

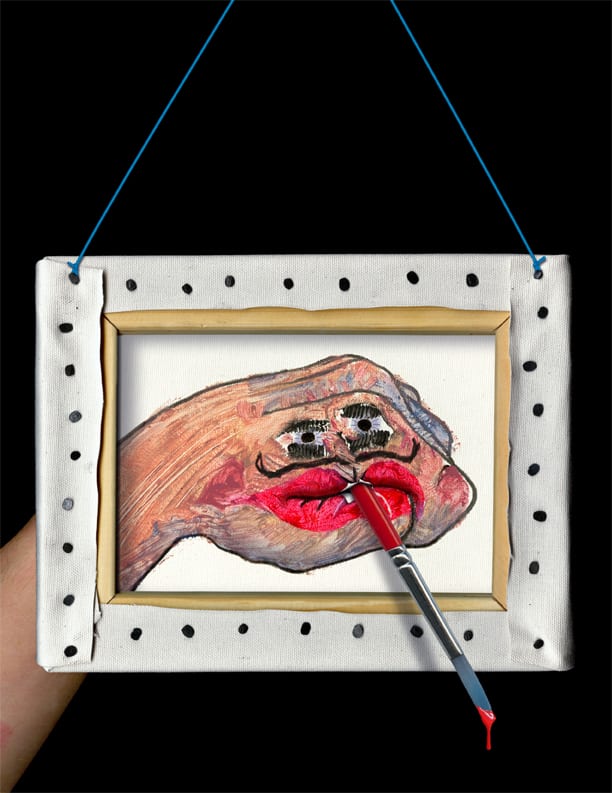

So what is it? Byrne’s succinct description of The Magician (published in an edition of 20 by Marquand Books) is: It’s set in a public bathroom. The Magician is this character that goes through and reconciles opposites. Every misunderstanding I have about the universe is documented in these objects. And creation myths, too. But it’s all tongue-in-cheek.” The Magician takes different forms. He is a sleeping figure. He is a hand. He is sperm. He is a cape.

Each book/object uses some element of stage magic in the Mandrake the Magician sense of the term. And each asks the viewer/user to in some way engage or create herself.

The first book, "Theogony", depicts a birth of the hermaphrodite, uses oversized panels and a transparent hourglass shape, as well as pages that open and shut, creating (bathroom) infographic transformations of time and shape in order to achieve the toilet expulsion of The Magician.

Maybe the most successful book is “Handmade”, which summarizes the basic concerns of Byrne’s: birth, death, eating and sex, but using entirely the stuff of children’s art, like paper plate drawings, hand puppets, leaves and hand shadows.

Maybe the most successful book is “Handmade”, which summarizes the basic concerns of Byrne’s: birth, death, eating and sex, but using entirely the stuff of children’s art, like paper plate drawings, hand puppets, leaves and hand shadows.

The same book depicts the actual hands (no longer shadow puppets) creating structures of heaven and hell.

And still another uses the basic form of the toilet and corresponding plunger to tell yet another creation myth of birth in a toilet.

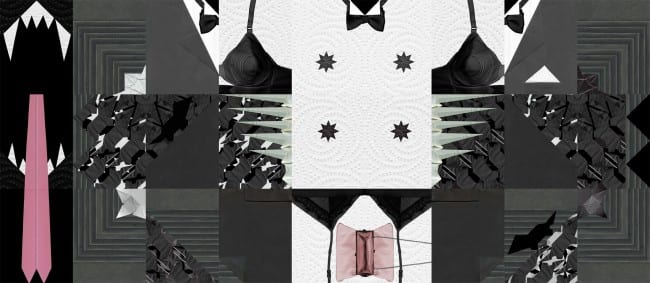

Maybe the most successful object is a folded poster, which, once unfurled, simultaneously resembles a magician’s cape and the actual hermaphroditic physiology. Bowtie included.

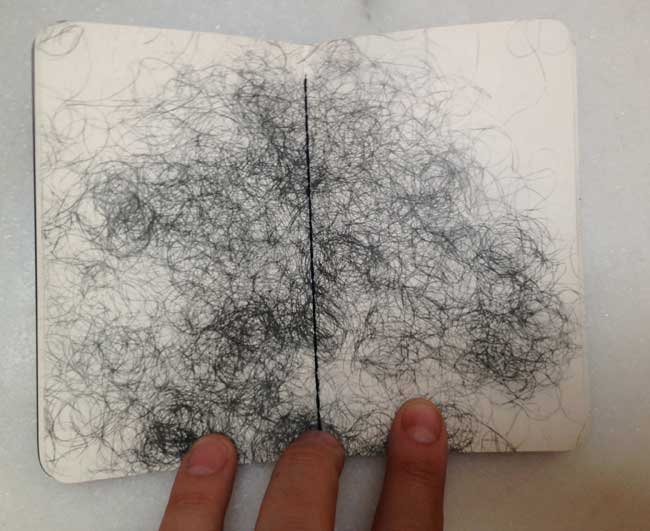

One of more ingenious bits is a moleskin notebook of pubic hair “drawings.” It functions two ways: What does one look down on when on the toilet? But then as a joke on the last 40 years of art. Are those process-based graphite abstractions? No, that’s pubic hair.” Or, as Byrne says, ““I’m not above school boy puns: That’s basically the magician.”

Another is a flip book of diamond patterns on toilet paper, emulating card handling.

Another book makes card patterns from sheets of toilet paper. Cards form patterns not for any real meaning but because they can, and life becomes a pattern of one thing on top of another, on top of another, until the whole thing gets flushed.

Then there are a series of comic strips printed on specimen slides, which can be viewed through the lens built into the box. The strips emulate cellular movement. Another birth, another melding of forms.

A hardbound standard size “sketchbook” containing Byrne’s studies for the objects and imagery functions not as a “behind the scenes look” so much as an artifact like all the rest. As if someone sat there sketching the objects in the box – deciphering it.

The box works because it’s not only a container. It provides a soundtrack (endless flushing) as well as a screen for an animation (figures flushing), not to mention a lens for viewing specimen slides.

That’s a brief laundry list of some of the components. The obvious comparison here is to Chris Ware’s Building Stories, but aside from the multiple-book idea and interest in schematics, there’s not much in common. Byrne is not interested in narrative per se, more like psychological and physiological events, which he manifests one by one in each book object. It’s a drop-in on a life, in a way. It’s not a-to-b. It’s not even a-to-b with lots of diversions. It’s a kaleidoscope of experiences.

That’s a brief laundry list of some of the components. The obvious comparison here is to Chris Ware’s Building Stories, but aside from the multiple-book idea and interest in schematics, there’s not much in common. Byrne is not interested in narrative per se, more like psychological and physiological events, which he manifests one by one in each book object. It’s a drop-in on a life, in a way. It’s not a-to-b. It’s not even a-to-b with lots of diversions. It’s a kaleidoscope of experiences.

When Byrne talks about the project, it’s Saul and Gary Panter that come up again and again. And yet there’s not a hint of either man’s style in the work. It’s more their presiding spirit. It is Saul’s willingness to lay down concrete images and make the viewer view with them as they are – to accept or reject a full thought. There is much about Saul that is influential, but no one talks about his actual (brilliant) thought-to-object process. Byrne gets that, and demonstrates it in another medium entirely.And it’s Panter’s intellectual omnivorousness. Furthermore, both artists, like Byrne, are not afraid to be “dumb”. To go for the toilet gag because it’s true and yet part of a large thought.

And so Byrne, playing dumb, uses “Magician” not as a caricature but as a category. It’s like “magician” because of course – in the hokey rabbit in the hat way, that’s how things are created. Something out of nothing: It’s magic. So we begin with a simple trick in which a hermaphrodite is created. And we move on and on.

The experience of dealing with the box (because it’s kind of intimidating, and you kind of know you’re in for a lengthy viewing experience, means you’re dealing with it) is funny. It’s almost like someone talking really fast, ideas tumbling out and then each idea spread out on a table individually and carefully constructed into material being, with a full recognition of the absurdity of the enterprise. I mean, that’s art, to an extent, but rarely visual books and rarely aligned with comics. Byrne’s unique achievement here is to have built an absurd object containing multiple meanings – to have performed the trick and allowed it to remain onstage to be unpacked, gazed at and puzzled over.