From the local and particular to the grandiose and universal Jeff Lemire easily and expertly guides the reader through life as experienced in the lonely Northern Ontario outback. The fictional town of Pimitamon near Timmins, Ontario acts as a natural stage for the unfolding dramas of everyday life in Lemire’s most recent work, Roughneck. “Pimitamon,” the Cree word for crossroads, neatly encompasses the conflicting and converging choices we make and paths we take as we wander through past, present, and future moments. Alcohol, drugs, domestic abuse, cycles of violence, family, Native heritage, and of course hockey enter and exit as they are re-called and repressed aspects of Canadian life. Lemire spotlights these underlying issues as the characters ebb and flow through the thicket of problems these issues create. Lemire’s relentless focus on feet, slowly carrying characters wherever they are going, emphasizes a journey that must be undertaken step by excruciating step.

The story begins effortlessly with the simplicity of Lemire’s inside cover page, a single image that adeptly introduces the remainder of the text. With such images Lemire demonstrates his candid ability to say so much with so little. A sparse tree, off-centred, standing in a bank of snow, alone in the dead of winter. The tree is naked and vulnerable, it stands prey to and yet against the elements, it reveals no answers. How big is it? A towering tree, a young sapling? It’s impossible to know. It is simultaneously natural and unnatural in its composition. It conveys, ever before the first question of the text “That him?”, the inscrutability, the barrenness, the isolation of Derek Ouellette. Asking the reader to come along on a journey through Pimitamon’s barren landscape and Derek’s mind to find beauty in the wild and stubborn nature at the heart of this man and the environment that shapes him.

Lemire’s quiet focus on boots throughout the book – walking, crunching, two and from – emphasizes the inward and outward journeys of his characters, walking along different paths that converge and diverge. Panel after panel, Lemire closely focuses on the step’s slow progress before revealing each character in splash page, overwhelmed by the enormity of their surroundings. For Derek, this is the familiar space of the ice-rink, the arena, a place that contains his successes, his failures, and his personal demons. For Beth, Derek’s little sister, her parallel trek is emphasized by her steady progress alongside the grandiose but bleak rural roadside. The burden of her life is evident with each crunch of her boots, a silent attempt to break the cycle of abuse that plagues her. Each step, a small victory, a small escape in itself. Lemire’s splash page of Beth shows her hugging herself against the penetrating cold, a gesture at once self-protective, standoffish, and self-loving. Beth must walk away to choose herself, while Derek must retrace his steps in a continual attempt to escape himself. Both are desperately trying to recover what they have lost in the bleak backwoods town of Pimitamon – perhaps their innocence, perhaps their will, perhaps their roots, perhaps their faith in justice. In the timelessness of Lemire’s quiet splash pages, only this steady metronomic crunching reverberates through the empty enormity of the barren landscape and the reader as each character retraces their steps in an consuming effort to finally set things right.

Those familiar with Lemire’s work, will appreciate the time he takes to tell this story. Time is both the agent and the enemy of the text, and is never rushed for need of action. Glenn Gould used to say about playing music, “it is not related to the striking of individual keys but rather to the rites of passage between notes.” Similarly, in Roughneck, it is not so much the moments of action Lemire strikes, but the passage of inaction that fills the reader with the reflections of the characters’ inner and outer worlds.

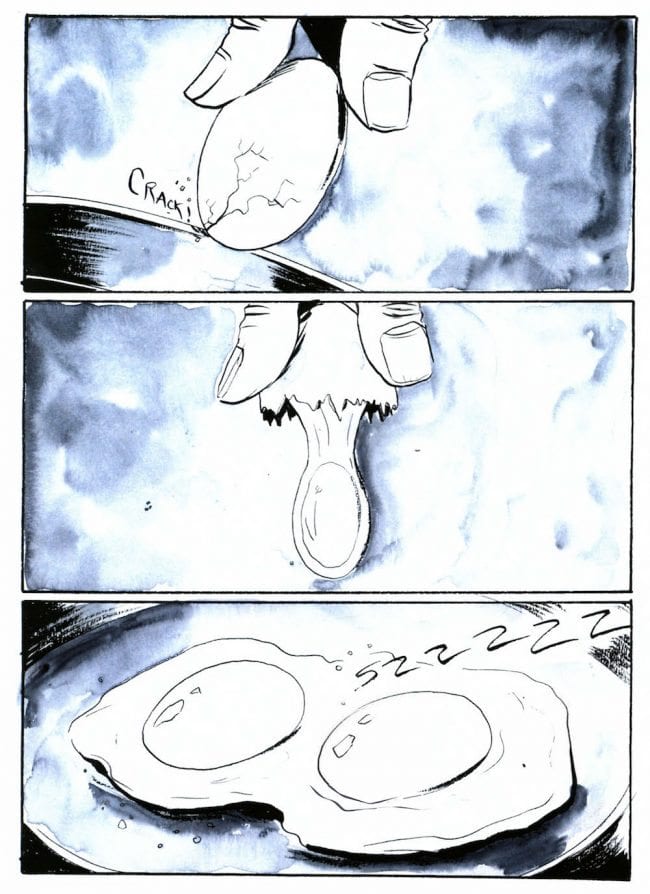

Derek cracks eggs over four hours across the span of one page. The cracking, emptying, and frying of eggs alone, takes up a timeless quality in three elongated panels which turns into an increasingly monotonous mosaic as those same panels are repeated four-fold, punctuated by revolutions of the clock. There is no break from this monotony, until the reader finally flips the page to go out for a smoke with Derek, whom we see through piles of garbage bags awaiting their inevitable removal. In this scene, the mindless routine action takes the reader into Derek’s head in which we find nothing more than the monotony of the routine itself, the smokescreen of avoidance, the suppression of other memories through this painfully dull repetition. Such understated moment-building creates the poetry of these characters lives and struggles as we are brought to witness the minutia of their existence, or perhaps the very essence of life itself. Lemire’s composition creates a unique musicality that emphasizes the rests as much as the striking of individual notes. In these moments, the reader pauses for breath, is filled with the life of each character, and accompanies the characters breath by breath. Lemire’s method is an incredibly intimate approach to story-telling, one that increases the story’s tension as multiple character perspectives merge on the page and unfold the story’s progress with bated breath until Lemire creates the next release.

Derek cracks eggs over four hours across the span of one page. The cracking, emptying, and frying of eggs alone, takes up a timeless quality in three elongated panels which turns into an increasingly monotonous mosaic as those same panels are repeated four-fold, punctuated by revolutions of the clock. There is no break from this monotony, until the reader finally flips the page to go out for a smoke with Derek, whom we see through piles of garbage bags awaiting their inevitable removal. In this scene, the mindless routine action takes the reader into Derek’s head in which we find nothing more than the monotony of the routine itself, the smokescreen of avoidance, the suppression of other memories through this painfully dull repetition. Such understated moment-building creates the poetry of these characters lives and struggles as we are brought to witness the minutia of their existence, or perhaps the very essence of life itself. Lemire’s composition creates a unique musicality that emphasizes the rests as much as the striking of individual notes. In these moments, the reader pauses for breath, is filled with the life of each character, and accompanies the characters breath by breath. Lemire’s method is an incredibly intimate approach to story-telling, one that increases the story’s tension as multiple character perspectives merge on the page and unfold the story’s progress with bated breath until Lemire creates the next release.

Lemire’s signature artistic style enhances Roughneck’s breathless quality and repressive atmosphere. Lemire is perhaps best known for his liquid like use of grey-tones which gives his characters and settings an otherworldly dreamlike quality. This liquid style is contrasted with the stark but messy inked line which comprises the boundaries of objects within the story world: a rough-hewn face, a tree, a cup of coffee. Roughneck is a satisfying extension of the artistic style Lemire has developed in his other independent graphic novels throughout his career: from the Essex County trilogy to his more recent collaboration with Gord Downie on Secret Path. Lemire’s traditional grey-toned colouration is used to great affect in Roughneck, emphasizing the somberness of both the external landscape and the internal state of his characters. However, Lemire’s use of colour in this work is nicely balanced in its reservation for intruding memories. Though memories may be thought of as a degraded accounts of what actually took place, in Derek’s violent flashbacks and induced drunken stupors, Lemire’s colouration creates a carnivalesque world that is more vivid than the character’s present reality.

A simple trigger, a dog in the alleyway, fires an unwanted flashback both powerful and gruesome in the character’s mind. We see as he sees, the bold spill of red against the serene green and brown muddiness of a winter landscape, the translucent shards of blue glass, and yellow smoke rising from an askew black frame. As Derek slams his eyes and the door shut on both his vision and ours, his addiction, his coping mechanism alcohol, unleashes a flood of memories upon the page’s surface and in bright, lurid detail. We, and he, are suddenly plunged into the seminal and horrible details of this character’s world – a past which haunts him and us even as it intertwines itself with the present. Through intertwining memories of hockey and an alcoholic father, the ice becomes the emotional battleground upon which a boy becomes man – for better or worse. Hockey becomes a mechanism for which Derek believes he can escape all that “Indian Stuff” he would rather not acknowledge.

A simple trigger, a dog in the alleyway, fires an unwanted flashback both powerful and gruesome in the character’s mind. We see as he sees, the bold spill of red against the serene green and brown muddiness of a winter landscape, the translucent shards of blue glass, and yellow smoke rising from an askew black frame. As Derek slams his eyes and the door shut on both his vision and ours, his addiction, his coping mechanism alcohol, unleashes a flood of memories upon the page’s surface and in bright, lurid detail. We, and he, are suddenly plunged into the seminal and horrible details of this character’s world – a past which haunts him and us even as it intertwines itself with the present. Through intertwining memories of hockey and an alcoholic father, the ice becomes the emotional battleground upon which a boy becomes man – for better or worse. Hockey becomes a mechanism for which Derek believes he can escape all that “Indian Stuff” he would rather not acknowledge.

Still, escape is short-lived and leads both Derek and Beth right back to the place they started, staring at the same crossroads they’ve been at one too many times. In Roughneck, the ice of the hockey rink quickly yields to the ice of the great Canadian outdoors, a surface for facing and rewriting one’s history to create a different kind of future. The ice becomes a conduit for acknowledging one’s heritage, facing one’s fears, and enacting one’s own manner of justice. A variant travelling route in the face of crossroads altogether with steps that “almost” lead to a future, always unknown, just out of reach. It is a journey each one of us has been familiar with at one point or another, which is what makes Lemire’s expression of this particular journey so poignant. Roughneck is a journey which details a minute and intimate conflict that expresses the land of Canada entire and all of its peoples, the desire to move forward step by excruciating small step to find a better future in spite of our troubled past.