In 1973, Terje Brofors, alias Hariton Pushwagner (b. 1940) sat in a window in Chelsea, London, drawing as if possessed. After several years living on the street, drawing for food and haunted by thoughts of suicide, he had found a home with the woman who would become his first wife. Perhaps it a feeling of living on borrowed time, now that he had a newborn daughter and a possible future, that motivated him finally to realize a project he that had first come to him in an LSD-induced haze some years earlier – in 1969 – in Frederiksstad in his native Norway.

Present at that moment of inception had been the Norwegian “beat”/SF writer Axel Jensen, with whom Pushwagner was collaborating at the time on stories and experiments in psychedelia, and instrumental in its formulation, title, and cut-up language was William S. Borroughs, of The Soft Machine, whom incidentally he had met in Tangiers a decade or so earlier.

Three years later, he bound together the finished work, consisting of 158 large pages, in a book. It circulated on the London club scene where it was appreciated by Pete Townsend and Steve Winwood, among others. In 1979, he returned to Norway and the book disappeared under circumstances that have yet to be explained. It resurfaced in 2002 only to be claimed by Pushwagner’s former assistant to whom he had signed away the rights to all existing work sometime during his years of living on the edge in the late 1990s. The artist won back ownership after a court case in 2008 and exhibited the originals to Soft City at the Berlin and Sydney Biennials, and they were published in book form in Norway. This helped him emerge from years of obscurity onto the international art scene and he has exhibited widely and to great acclaim since.

Pushwagner himself has stated that everything he has done since springs from Soft City. This is clear. It presents us with the kaleidoscopic view of modern society that has always characterized his art. It is the blueprint for his almost maniacally fastidious, densely packed visions of society as a machine that have made him famous. It is furthermore the direct model – in terms both of individual motifs and narrative – for what was previously his best-known work, En dag I familien Manns liv (‘A Day in the Life of the Mann Family’), which was published as a series of silkscreen prints in 1980 and developed further in a number of paintings after 1988.

In Soft City we witness a day in the life of an average family in a metropolis populated by average families. George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun” is the co-opted counter-culture overture; the sun gazes at us with the eye of the New World Order – the one we know from the pyramid on 1$ bill.

The couple start their day medicating their dreams away with “Soft” ‘life pills’; we see the endless lines of office drones in their cars, their vast parking towers and panoramic office landscapes; we see women dropping off their children at vertiginous day care farms to spend their day shopping in the city’s “Soft” megaplexes. Everything is overseen electronically by the ruling class, which itself seems just as susceptible as its subjects. All while the gears of war churn beyond the horizon.

Soft City thus is a natural extension of the portrait of the individual as a depersonalized unit in society as machine that has been a central narrative in critical discourse in the modern era. Walter Benjamin’s characterization of the person as an automaton, Fritz Lang's Metropolis, Aldous Huxley’s clinical dystopia, the assembly lines and buzzing wheels and cogs of Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times, and of course George Orwell’s Big Brother, form the basis of Pushwagner’s vision, while his formal presentation is in the tradition of the socially engaged modernist woodcut novels of Frans Masereel, Otto Nückel and others, as well as the disillusioned counter-culture of the 70s, notably its compromised pop art.

It would all be smotheringly rote if it were not staged with such conviction. Symmetry and synchronicity are the guiding principles. The books many panoramic spreads are ordered symmetrically, with the straight lines and angles of oppression subversively rendered in the artist’s imprecise and unruled, shaky hand. Synchronicity provides the structure of the narrative – the actions we witness are repeated ad infinitum by countless families across the at times almost diagrammatic compositions. Guided by their mothers, the children wave like machines to their fathers. But here and there, subtly, small human deviations are suggested between individual figures.

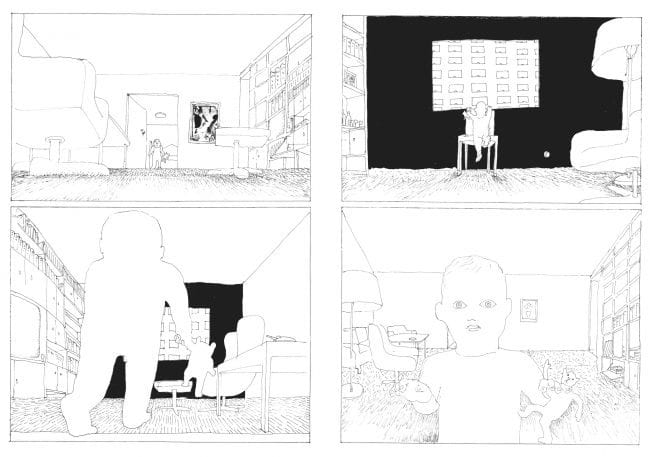

Accentuating its quiet insistence on individual humanity, but in a particularly bleak manner, is the fact that we experience the story’s opening and closing through the eyes of a child. It is named Bingo – suggesting stunted imagination on the part of its parents, a banalization of the gift of childbirth that we know motivated the artist. It is caged in its crib most of the time, but at the beginning, at dawn, before the parents awaken and the Machine activates, it is shown capable of climbing out and exploring the environment on its own.

Its consciousness is presented ambiguously. Although only a toddler, it thinks in full, multisyllabic sentences, declaring its status in the “soft” system: “I am a baby. Time to get up, move around and find out what’s happening.” On the one hand it indicates awareness beyond the boundaries set by the system, but on the other it reads almost like programming – these are the things a child is built to do – suggesting that automation is inborn, that the Machine is us. But at the end, as night has fallen, the child does not shut down, and that may Pushwagner’s slim assertion of hope. However, he simultaneously, and almost apocalyptically, indicates that it may be too late.

Soft City represents an artistic vision in its embryonic form, but its precocity makes it more compelling that much of what the artist has produced since. Its critique is heavy-handed, almost didactic, and the drawing uncertain and unclear in places, but it is crafted with genuine nerve. One senses acutely the urgency the artist must have felt back then, sitting in that window.

The book is beautifully designed by Chris Ware, who also provides an introduction. An informative afterword by Martin Herbert rounds off the package.