The precocious, hyper-articulate adolescent is a ubiquitous and well-catalogued type, and with good reason; it’s not hard to find a way into a character who is charismatic and forthcoming, as either an author or a reader. Charles Forsman’s gift, however, in works such as The End of the Fucking World and Celebrated Summer, has long been to convey the inner lives of teenagers whose emotions and troubles exceed their ability to express them. I Am Not Okay with This is Forsman’s latest variation on this theme, focusing on Sydney, a lonely teenager with a more than passing and less than explicable resemblance to Olive Oyl, muddling through the days and being slowly overtaken by her emotional turmoil in the wake of her father’s death.

I Am Not Okay with This leans toward the episodic, with each episode feeling less like the progression of a story and more like another brick in a wall. It’s held together by Sydney’s narration, which takes the form of a diary her guidance counselor asks her to keep. Syd tells us her English teacher praises her creative writing assignments, suggesting a fertile imagination, but the voice we hear in her diary is blunt and unaffected, as though she is trying to minimize her depth of feeling even in her inner monologue. The diary entries could easily be a limiting factor, not allowing the story breathing room outside Syd’s head. but Forsman deploys them savvily. He keeps the story tethered to Syd’s perspective while quietly revealing the limits of her perception in vignettes where Syd’s words are, if not exactly in contrast, in a kind of discordant harmony with the panels below. In the “Lasagna” chapter, Syd vents about her frustrations with her mom and their relationship, and we see her words overlaid with images of her mom struggling through an exhausting day of work as a diner waitress and gripped by grief alone in her car. That both Syd and her mom are on parallel tracks of suffering and unable to reach each other through it is one of the most heartbreaking currents in the book.

The bifurcated narration and imagery is even more striking in the “Baby Jesus” chapter. As Syd reflects on her friend Dina, for whom she harbors a painful crush, we watch as Dina and her abusive boyfriend Brad get into a violent argument over Dina’s accidental pregnancy. The panels are static, framed from outside the car where their argument occurs invisibly but certainly not inaudibly. Just as Dina keeps Syd at arm’s length, knowing that permitting too much intimacy blur boundaries she wants to keep intact, Forsman holds us at a remove from the scene and its violence.

Forsman’s ability to maintain the immediacy of Syd’s point of view without completely surrendering to it results in a complex piece of work and one of the most honest depictions of the emotional telescoping effect of both depression and adolescence. His empathy for Syd never wavers, but he is unflinching in depicting the ways she falls short of empathizing with others. Syd is preoccupied with the idea her own selfishness, but, overwhelmed by her emotions, she can't see past the fog to connect with the people in her life and is often destructive to herself and others.

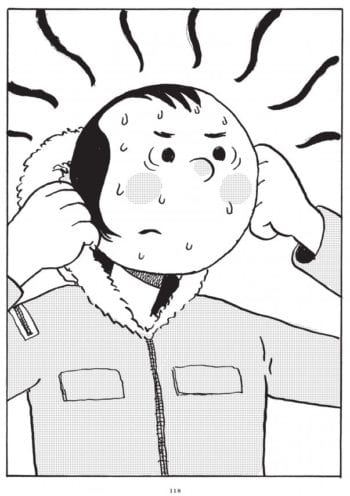

Forsman literalizes this idea, making her anger and grief take the form of an ambiguous type of telekinesis. It's painful to her, painful to others, blunted by drugs, and heightened by pleasure and anger alike. It is also inherited from her father, a veteran who returned from Iraq with an unendurable case of post-traumatic stress disorder. Syd’s powers provide a plot engine, escalating her anger and desolation into violence and subsequent regret, but as a metaphor for mental illness they feel too familiar. The atmosphere of looming darkness is palpable enough without having to physicalize it. The device offers a few moments of body horror (the conclusion to “Last School Day” in particular jumps to mind), made more visceral and shocking in the context of Forsman’s tenderly cartoony character designs, but the telekinesis feels like one element too many in a story that is rich enough without it.

Forsman literalizes this idea, making her anger and grief take the form of an ambiguous type of telekinesis. It's painful to her, painful to others, blunted by drugs, and heightened by pleasure and anger alike. It is also inherited from her father, a veteran who returned from Iraq with an unendurable case of post-traumatic stress disorder. Syd’s powers provide a plot engine, escalating her anger and desolation into violence and subsequent regret, but as a metaphor for mental illness they feel too familiar. The atmosphere of looming darkness is palpable enough without having to physicalize it. The device offers a few moments of body horror (the conclusion to “Last School Day” in particular jumps to mind), made more visceral and shocking in the context of Forsman’s tenderly cartoony character designs, but the telekinesis feels like one element too many in a story that is rich enough without it.

I Am Not Okay with This ends tragically, with Sydney unable to overcome her sorrow and isolation. In a crushing moment, Syd sabotages her relationship with the school counselor she reaches toward for help, and what follows feels somehow both inevitable and lamentably preventable. It's a credit to Forsman that he can indulge in this kind of dramatic irony without lapsing into cruelty or sentimentality; the ordinariness of his characters and the world they populate makes every turn and coincidence feel organic. Sydney is the kind of lonely person who so easily fades into the background, it's hard not to wonder how many like her your eyes have passed over without noticing. In I Am Not Okay with This she is, momentarily, indelible.