Perhaps the primary distinction of the artist is that he must cultivate that state which most men, necessarily, must avoid; the state of being alone. - James Baldwin. “The Creative Process”

As Tolstoy almost said, in high school, all alternative cartoonists are the same. Bullied. Ridiculed. Shunned. No one who has read R. Crumb (or any of several others) will be surprised by Purgatory ("A Rejects Story"), by Casanova Nobody Frankenstein. But it still impales the heart. Crumb, at least, had sisters and brothers. Crumb, at least, was white.

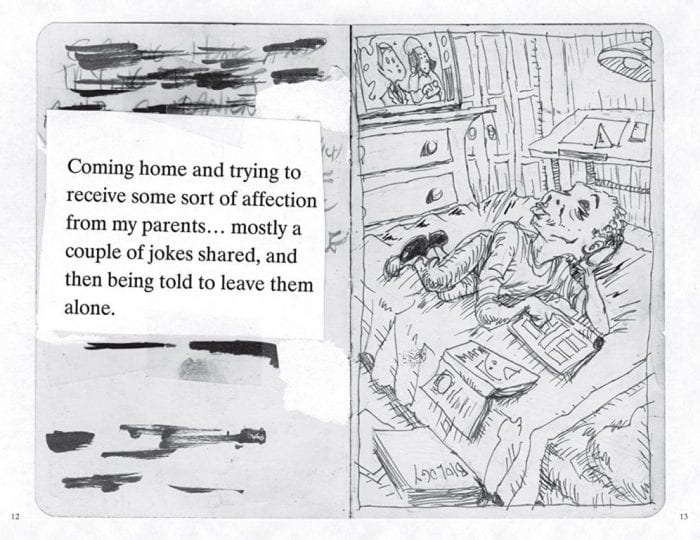

“To be almost alone...,” begins Purgatory. It picks up Frankenstein at 13 and, through one day’s compression, carries him through high school. He travels, on foot or by bus, “alone.” At school, he feels secure only in study hall, “alone.” At home, he closets himself in his room “alone.” His classmates are “beasts.” Sitcom characters are “closer” to him than his parents.

His solace is comix, cartooning, art.

Purgatory is slight: 6” x 4" x 1/4” Thirty-seven pages of text on the left of the fold, each balanced by a black-and-white drawing on the right. Frankenstein is best known for the head-clubbing Adventures of Tad Martin (see my review). That came spiked with sex/drugs/violence. This has none. This is softer. The sun shines at the tunnel’s end.

For the four years covered, Frankenstein “contemplated suicide...” But his pain had been “the best thing that could have happened....” “(E)very step... (chipped) off another slab of hardened grime from my soul.”“Stay alive”; things “change.” “An honest look into your soul” leads “to actual living.”

It is a survivor’s message. It is an artist’s. The prose is clear and clean. Sometimes the art reflects it. Sometimes it adds to it.

From the art, the uniform of Frankenstein’s father reveals him as a policeman. The depiction of Frankenstein’s mother reveals her to be white. Through the art, Frankenstein’s subjective sense of the world is expressed. In the locker room, one of the (modestly) prose-described “overly-aggressive... athletes” becomes a KKK-hooded nightmare. The class-room “beasts” are all snouts and gaping, sharply fanged mouths.

From the art, the uniform of Frankenstein’s father reveals him as a policeman. The depiction of Frankenstein’s mother reveals her to be white. Through the art, Frankenstein’s subjective sense of the world is expressed. In the locker room, one of the (modestly) prose-described “overly-aggressive... athletes” becomes a KKK-hooded nightmare. The class-room “beasts” are all snouts and gaping, sharply fanged mouths.

Then there is Frankenstein’s portrayal of eyes. Especially his. Haunted. Dreamy. Startled, Scared. Windows to the soul, I’ve heard. Sometimes his eyes are simply lovely, the promise in them immense. Then, at the end, the author’s photo shows them opaque, sealed behind Steampunk shades, above – is it? – a Mona Lisa smile.

With the book in our hands, with the triumph it has expressed, we may smile back. Purgatory is, I hope Frankenstein won’t be offended, a sweet book. That it could issue from his ravaged earth reminds one of hope.

In garbage, say the Buddhists, the rose.