We asked Phoebe Gloeckner (The Diary of a Teenage Girl; A Child's Life) to interview Julia Gfrörer (Black is the Color; Laid Waste; the forthcoming Mirror Mirror II) about her life and work. The two artists spoke on November 28, 2016 and edited the transcript in the weeks since. -eds.

JULIA GFRÖRER: Hi, how are you doing?

PHOEBE GLOECKNER: You're in New York, right?

Yeah.

How are you doing this morning?

I’m good, pretty good. How about you?

Pretty good. I'm really nervous about doing this, because it's not what I've done before so...

Yeah, me too.

Yeah. So I guess let’s do it. And also I'm nervous about recording.

And do you have your recording stuff all set up?

Yeah.

Yay!

So hopefully it will work.

I feel weird about this FaceTime. I feel like I look funny. I'm gonna have a cigarette.

I have my fake cigarette.

Is that an e-cigarette or is that something else?

Yeah, it's an e-cigarette.

Whoa. I've never seen one that looks like that.

It’s really good because you don't have to deal with the juice. You just pull this thing out and replace it.

That’s cool.

Yeah. And it's totally made me not want cigarettes. I mean, it's better than a cigarette for me.

Oh, cool.

Yeah.

[Shuffling about.] I'm just looking for my lighter. Okay so you have questions…

I've got lots of questions but I'm trying to figure out a way to like... uhh, God I'm so bad at this, aren't I? Okay, I'm trying to remember like the first time we met... Do you remember?

Yeah, I remember. It was at CAKE [Chicago Alternative Comics Expo] and, if you remember I was friends with Sean [T. Collins] and he is just crazy about you and he’s like, “She's amazing. I'm so excited for you to meet her…” And wait… I'm going to bring my whole pack of cigarettes with me...

Where are you going?

Just out in the backyard.

Because you're not allowed to smoke in your apartment… Okay. So you got to CAKE and saw that we were sitting next to each other and... was that Sean's doing?

No… I don't know how it ended up like that… I think the organizers do that.

Okay.

And then you got there, like late, and you seemed really freaked out, and you were like, “I don't know how to display these. How much should I charge for these? Can you watch them? I have to go get something back at my hotel…” And then you left again and I was like, "Sean, what the hell, is she always so freaked out like this?"

My only excuse was that I'd never been more depressed in my life.

Really?

Yes. That year was like middle of like the four or five worst years of my life.

I’m sorry.

And I didn't know why I was at CAKE or even why anyone had wanted me to be there. I needed to sell my work but I didn't even fucking know how. At the time, my self-esteem was very low and I had no sense of who I was, not so much as an artist but as a living being. I felt so withdrawn that no matter what good things were said to me, they just didn’t sink in. I was so unhappy, I walked around like a ghost, wondering if and why I was alive.

You seemed kinda manic almost.

I wouldn’t have described it as manic, but I was unmoored. I was not navigating well through a terrible divorce. Life felt so tenuous. Most things that had seemed constant in my life had been taken away. I was lost. I was like a baby bird fallen from its nest and flailing on the ground, fighting for its life.

I guess that's manic, you know, not in the sense of elevated mood but with a lot of nervous energy.

I’m sorry you had to meet me under those circumstances!

No, that was just my first impression and you weren't around at the table much that day anyway. Later, I saw you at the party.

Right!

We were on the roof and we got caught in this rainstorm and had a really intense conversation and there was lightning all around us. It was a really big deal to me. I was thinking, “This is amazing. Phoebe's amazing.”

I was thinking the same thing. “Julia’s amazing! Who is this creature?” That meeting in the rain gave me a chance to atone. It’s not easy meeting young cartoonists who seem like they might be interested in getting to know you when you’re at the lowest point in your life. All hopes of making a good impression are quickly dashed. Even worse, it’s even harder to inspire empathy when you present as a madwoman. But talking with you was a great distraction from my life. You were fascinating, and I hadn't even read your work yet.

You said, in one of your other interviews, that when a fan speaks to you about your art you sometimes find it hard to connect with them. There is something intrusive and vaguely threatening when a smiling stranger approaches you as if they know you. They do know you, in a way, through your work, and might be convinced of that whether you were dead or alive. This kind of “knowing” can be alienating. A reader understands works of literature in the context of their own experience. They see you as an extension of the work, and through the same filters, in the same contexts that they find meaning in the work. It’s overwhelming when their gaze shifts from the work to you, the author. You said that if you succeed in getting beyond this point and find that you have common interests beyond your own work, the fan-artist barrier melts and you’re able to relax and actually enjoy the interaction.

Yeah, totally. One thing that Sean said about you before I met you was that you were… I don't know how to describe it... not open exactly, but as we’re talking now, I feel like there is the sense that there's not much boundary, like you're going to take the things that I say and internalize them. And I do that too when I talk to you, like everything really goes into me. Do you ever have that sense that you have just a thin skin between you and other people?

In a way, I guess. I feel so much a sense that I am everybody, but yet sometimes I feel totally alone, which I guess is an odd thing to say. I find some comfort in recognizing connections with everything and everybody, because it does make you feel at one with the world. But paradoxically, communion with the other is not always possible. When attempted, it is not as always as satisfying as you imagine it will be, and in the end you realize that there will always be that skin, that separation between yourself and others.

Why are we talking about me, anyway? Let’s talk about you!

I don’t know, but I definitely relate to everything you’re saying.

I think we’re just finding the common ground between us. Anyway, I was reading the other, extended interviews with you, the one by Sean Collins and one by that other guy, what's his name?

I want to say the first one is with Jason Leivian, the owner of Floating World Comics in Portland.

Yes, you’re right. After reading those interviews, which are both great, I was wondering what could I add? I guess maybe the fact that we’re both creators, we write and draw, is a difference. So how does that make the possibilities for this interview different?

I think that it can be hard for people to understand… you know, Sean writes comics so maybe it's a little easier for him to understand. There's like a weird magic that happens in between whatever is going on in your life that makes you make the thing, and then the finished product, which is the thing that people [your audience] interact with. The relationship between what caused it and what you did or what your process is in making it and then the final thing is obscure to people when they see the finished work. Maybe it seems kind of easy, like I don't want to say it is overlooked, but you know, once it's done there's a sense that it feels like it was inevitable—of course this would be the finished product of what happened here, but you know it's not really like that.

I can’t visualize a person that I’m talking to other than myself. I don’t know what that person would want. I don’t have a sense of what the book is going to do once it’s in the world. I make it because that’s what I do. What happens when I want to express myself, is that it comes out as stories. And then I like to draw, so I draw the stories. But I don’t have a sense of what my audience is, other than, maybe, if it’s me. If there’s something that I need to externalize — I need to get it out and put it down somewhere.

But when you think of yourself — well, when I work, I’m generally conscious that I am the sum total of every generation of human beings before me. And I’m connecting to people laterally as well. When I get to that point, I lose self-consciousness, because I’m very aware that anything that happened to me is not unique. I have no shame about it. And it isn’t me. Or it doesn’t matter. This question of when — when people ask you about the sex scenes, and they kind of think, “Oh, my God, she must be a freak.”

[Laughs.] Right.

And that’s happened to me, too. People ask, “Did this really happen to you?” All this crap, which to me just seems like a non-question in a sense. But how do you respond to the confusion of the audience, fans? They look at you, and they look at your work, and they either make assumptions or have a picture of you that kind of smells like raw, creepy sex? [Laughter.]

Hmm. If people make assumptions about what I’m like because of my work, probably some of them are accurate. I don’t feel like it affects me. What people who don’t know me believe about me isn’t really my business, exactly. If it’s helping them to have a relationship with the work, then I feel like that’s good. That’s fine. Mostly the assumptions that people make about me are flattering, or maybe not accurate to how I see myself in other areas of my life, but good for my brand or whatever. A lot of people, when they meet me, assume that I’m a Satanist or a witch. Which, maybe, in an abstract, symbolic way, is accurate. But in a literal sense—of my beliefs and practice—is not accurate. When I was in college, I made a lot of work about — I was really interested in martyrs, and the saints. I still am, but I don’t make as much work about it now. I remember one time, being at a crit or something, and somebody saying a curse word, and then apologizing to me, and I was like, “What?” And I realized they had all assumed I was a very devout Catholic because of this work. That made me feel like the work was not interrogating the subject matter deeply enough. That it seemed like I was taking it at face value. I think that’s one of the reasons that I moved toward occult and supernatural. Stories about Christian miracles are still supernatural, but more fairy-taleish imagery that people wouldn’t take at face value so much. Or, that it would be easier to understand as something that I was trying to recontextualize, or understand, as a mythical entity.

Without the heavily charged Christian associations?

Yeah. What’s always been interesting to me about those stories is this narrative of physical suffering being redemptive. You enumerate these horrible, torturous experiences that this fictional person has had, and then that proves that they were really worthy, it proves their love for God or whatever. And in medieval romances and stuff, which are written in a similar way, where the trials that the lovers go through prove that their love is really special. And that’s such a beautiful, romantic, and seductive idea, that isn’t reflected in reality, I think. The suffering that you go through doesn’t necessarily mean much about the quality of the thing that is causing you to suffer. It’s probably not necessary. I don’t know if this is real, I’m sure that some people have the experience of — say, like marriage. You fall in love with somebody, you get married to them, and you have small disagreements, but you have a good partnership that lasts for a long time. That wouldn’t be more real if you had to be refugees together, move to other side of the world to be with this person, or if they died, and then you spent your life memorializing them. That wouldn’t make that relationship more real if suffering was a part of it.

You were quoting when you said that love is a trick on humans…

A discourse of suffering? [Laughs.]

No, you said it was something that had been intended to blind and cripple humans, so they didn’t realize how meaningless it was to attach those emotions to something else. I can’t remember the quote…

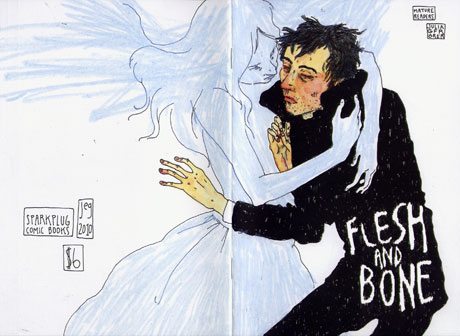

Oh, that’s in Flesh and Bone. I think that the witch talks to a demon, and the demon says something like, "Love is an illusion to distract humans from questioning God."

Flannery O’Connor, in Wise Blood, says, "Jesus is a trick on n******s.”

[Exhales through teeth.] Yeah.

To give them this belief that, in a sense, controls them.

One of Jenny Holzer’s truisms is that romantic love was invented to manipulate women. [Gloeckner laughs.] I think those things are true. Religion is the opiate of the masses. All that stuff. But at the same time, I think something like the love you have for a romantic partner, for your children, those are the things that life meaning. I read a Carl Sagan book years and years ago, I think it was probably Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. One of the things he talks about is how love is an adaptive trait that animals have to insure the survival of the group. If you don’t love your children, then you don’t take care of them, and then the species dies out. So, it’s a survival mechanism, like a program that you run to make sure that your hardware stays intact.

Right. And there are plenty of humans who have no children and aren’t in any relationship, but still they feel love. Maybe it’s to their friends, maybe it’s to their animals, maybe it’s to their books. Maybe it’s to their own thoughts and adventures.

And there are people who feel no tendency towards, or need for, romantic love in their lives. But it’s something that I can’t relate to. I don’t address that in my work, because I can’t understand it.

But, on the other hand, what you do write about is about what you don’t understand. But I guess you were saying that —

Things in my own experience that I don’t understand. [Laughs.] When I’m doing something, and I’m like, “Why am I doing this? Why do I feel like this is the thing I need to do?”

Yeah, that’s often when you know that you have to do it, because you have to find that answer. Okay, good.

Well, I am changing the topic entirely now. As an artist, I can see clearly, we are two totally different generations. I could be your mom. That makes me think about people who really inspired me or mentored me, so to speak, in informal ways or accidental ways, when I was your age, younger, older, whatever. It’s a funny thing, because as an artist, I always felt like I was in this little bubble. Maybe people had influenced me, but I felt, totally, like I was my own little planet. Of course, it’s an illusion. Things inspire you, and make you do what you do. I was wondering: I haven’t seen a whole lot written about your early life, but maybe I missed it. What brought you to making comics? When did you do your first comic?

I drew comics when I was little, just because I was drawing all the time. When I was in high school, my best friend and I published a zine, so I would do comics in the zine. Or one of the things that I would do was make little finger puppets of different characters, and then write a little play that you were supposed to act out with them, and put that in the zine, and you were supposed to cut them out. But I wasn’t really thinking of that as being my art form. Up until I was in high school, what I really wanted to do was, I wanted to a be an Egyptologist, or to study languages, or something like that. When I was a teenager, when I was in high school, I was taking French and Latin. You were only supposed to do one language, but I signed up for both. And then, in my spare time, I was studying Japanese. One of my best friends was an exchange student from China, so she was teaching me Mandarin Chinese. I took a class over the summer to learn American Sign Language. I was really interested in philology. When I was younger, when I wanted to be an Egyptologist, I learned to read some Egyptian hieroglyphics. All that stuff was what I was really interested in.

But when I was in high school, I got really severely depressed, and I think — I didn’t really make this connection until just recently — I began to feel like going into academia, like, I wasn’t going to be smart enough, or it was going to be somehow like showing off, or something. I wanted to do something more modest. Art was the only other thing I felt like I was good at. I was like, well, I bet I can learn to be really good at drawing. So I went to art school, and I majored in illustration, because I loved to read and I loved to draw pictures of the things that I was reading about. But the illustration program in college was really commercial based, about designing logos, and I was like, this feels crummy.

I was raised Quaker, and there are conservative Quakers, but the type of Quakerism I was raised with was very liberal, very social-justice-focused, activist. A lot of ex-hippies became Quakers, it seems. I was really uncomfortable with [the illustration program's] level of commercialism. Being involved in any type or marketing or advertising just seemed really dirty to me. It just seems manipulative and insincere, and then my art was going then be used to trick people into giving their money to people who already had a lot of money.

Then, because I was learning about art history and stuff, that was when I really became more aware of contemporary fine art. So I switched to a fine art major, and, I guess, conceived of myself as becoming a fine artist. I think that my plan was to have a day job, and hopefully have shows in galleries, so, whatever. My work was always really narrative, and my teachers and advisers were kind of like, well… I had an art school boyfriend, who, his big senior project was he cast in plaster little letters of the alphabet — every letter and number and punctuation mark in book of Genesis. And then he had this huge pile of plaster letters that were maybe two inches high, and that was all he did all day, was just make these letters.

Every letter in the Book of Genesis? That must have been a very heavy pile.

Yeah. It was massive. He moved it with a forklift. And then he displayed them all in a pile. One time I was talking to him, and I was like, “You don’t like my work, do you? You don’t like my art.” And he said, “Well, I think of it more as illustration.” I think he thought he was being diplomatic, but it felt very disdainful.

It’s funny that the word illustration, to me — and maybe, to many artists who are also writers, and combine these things — illustration is pejorative.

Yeah.

And also, in the real world, because typically, if you illustrate a children’s book that you haven’t written — if you’re working with an author — you will often get second billing. Some authors see illustrators as hired hands rather than as collaborators or interpreters of their work.

Yeah, I think maybe the idea, the thing that people at school were taking issue with, was that it seemed to them like I was just regurgitating other people’s stories, or the imagery was already there.

Right, so your interpretation was discounted.

Like it wasn’t original enough.

Right.

Maybe it wasn’t. I don’t know.

Let’s talk about your process. When I’m writing books, it takes me forever because I never, ever outline anything. And I resent it. I just can’t do it because I don’t want to know exactly what happens next, I don’t want to know how everything’s going to fit together until the very end. How do you generally work?

So you just do one finished page at a time?

Yeah, but then I’ll often discard pages. Well, now I’ve been working on a very long novel. I’ve made progress in several different directions and then abandoned them entirely. But, then maybe I’ll go back and pull stuff in. It’s a way of working which the process is my joy. And, I’m not going to tell myself where I’m going to end up, I’m going to find it. I know that in the end when I finish it I’ll have this other type of joy, but I will have abandoned that adventure. It’s almost something that I fear. [Laughs.]

It’s scary in between projects. That’s not a good feeling.

It can be really depressing. You can feel like you have no reason to live because you’ve devoted yourself to something for so long.

My first longer project — I don’t remember which one it was, maybe it was Black Is the Color. Greg Means [who does comics under the name Clutch, or did. He runs Tugboat Press, or did. He’s a Portland guy] was like: “Let me give you some advice. Before the book comes out, you need to have started your next book. Because if you haven’t started your next book, when the book comes out, you’re going to feel this horrible decline as the excitement of the book starts to wane. And you’re going to feel lost. So you’re going to have to already have something in motion.” And I did that. That was good advice. I try to always follow it.

My first longer project — I don’t remember which one it was, maybe it was Black Is the Color. Greg Means [who does comics under the name Clutch, or did. He runs Tugboat Press, or did. He’s a Portland guy] was like: “Let me give you some advice. Before the book comes out, you need to have started your next book. Because if you haven’t started your next book, when the book comes out, you’re going to feel this horrible decline as the excitement of the book starts to wane. And you’re going to feel lost. So you’re going to have to already have something in motion.” And I did that. That was good advice. I try to always follow it.

Right. You know, I was also raised a Quaker.

Oh, you were?!

Yeah, I was.

How did I not know that?

I don’t know. We just never talked about it. But I was raised in Philadelphia until we moved to San Francisco before I was a teenager…

So, you were in Quaker territory.

One set of grandparents were Presbyterian but the others were Quaker. My grandmother was a doctor, and she was very devout and involved in the Quaker community. We went to Quaker schools all through elementary school. I think I always liked this idea of, God doesn’t need a vehicle through which to speak to you. That we all have the inner light. That was the most beautiful thing, whether religious or not. It feels so inclusive. It loses that hierarchy, which is so oppressive in many religions and governments and organizations.

I haven’t seen you talk about your father much in print. I’m wandering, again, about the young Julia. You talk about your mom, the Jungian psychologist. Was she an academic, by the way?

She was in private practice for a while. She doesn’t probably want me to talk a lot about her real life now, in public.

Why? Is she a criminal? [Laughter.]

She’s just very private.

Whatever that means. My mother says she’s very “private,” too, and I honestly don’t know what she’s talking about.

Really?

Yeah.

But my dad — my parents split up when I was really little, but they lived a block away from each other, so I saw my dad a couple times a week. My relationship with my mom — because I’m an only child, and because it was just the two of us in the house — was always really intense, and really my primary relationship in my life. So I didn’t get really close to my dad, because I felt like it was betraying my mom. My dad is a really cool guy in a lot of ways. He makes documentaries. For the last, I guess, 20 years or so, he’s been self-employed. He has his own documentary company in New Hampshire. He was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War. He did alternative service with the National Welfare Rights Organization in Washington, D.C.

When you say, he has a documentary company, do people come to him, saying, “I want to make a documentary about this?” Or, is it self-driven projects?

He does video production for hire, but also does his own projects. And sometimes they’re about history and stuff. Mostly they’re about different towns in New England. He’ll go there and stay for a while. Get to know people and then do a piece about the town. They’ve been shown on the History Channel, and they’ll sell them in gift shops and stuff.

Can you name a topic or a title?

He did one about Concord, the town I grew up in in New Hampshire. I’m not going to be able to think of one now. He did one about the Cold War that was called Rights & Reds. He did one about William Loeb, the publisher of the Manchester Union Leader.

So when you talk about how your parents made you intellectually, what were their contributions?

From my mom, I think, one of her most significant contributions to me as an artist is that she taught me a lot about analysis and symbolism when I was little. She taught me to interpret my dreams really young, which has been really valuable to me. About archetypes, and mythology, and all that Jungian stuff. Translating the drama of universal story into understanding it as a journey of the self.

With my dad, I think a lot of what I got from him was more practical. My dad has always been a real workaholic, and seeing him get absorbed into whatever project he was working on… He taught me, because he would give me little jobs to do. I did work for him, running camera or editing, up until I moved out of New Hampshire as a teenager. Learning about composing and image, or looking for the parts in the story that you want to interrogate further. When I was really little, he was working for the local cable station doing some news and current events, too. My stepmother is also a journalist. She was a TV news reporter. With them, any conversation about current events, or — not even current events, really, anything — it’s a lot about what’s the story, what’s the angle on the story, what are the things being discussed, what are the things not being discussed, and why? Considering how a narrative is a created thing that is separate from reality. You know?

Yeah. And yet directly related to reality, and has the power to create new perceptions of reality.

Aesthetically, my dad used to take me to go see the Bread and Puppet Theater. It’s a radical puppet theater in Glover, Vermont. They do — I don’t know the history of theater very well, but I’m sure Brecht is an influence — plays about history, socialism. Aesthetically, they do a lot of woodcut and letterpress art that you can buy for very cheap from them. They have a whole philosophy. They would publish what I would call zines, too. The idea being art should be accessible. It should be relevant to the lives of normal people. It should empower and honor everyday people. They would have performances that you could be a part of. You could sign up to be in this or that performance, and then they would give you a costume and be like, “OK, you walk in here, you say this, and then we all do that.”

On my 7th birthday, actually, they came to Concord. They just happened to be there, then, and they did a performance about a rebellion of rubber tappers in Brazil that had happened not that long ago — in the ’80s, I guess — lead by a man called Chico Mendes. I got to be in that, and that was a really exciting thing for me. I got to be a red rainforest bird. I think part of what was so valuable about that to me was the sense that the art was coming from people. People were making it; other people were participating in it. It was really accessible, and it wasn’t a thing that was handed down from on high; and it wasn’t in a museum. It was a manifestation of community and of real conversations.

Right. Just in the simple fact that you, a redhead, got cast as a red forest bird. It suspect it was a response, in part, to your appearance. “OK, Red. You’re the bird.” [Gfrörer laughs.]

So, both of your parents — your dad was talking about the significance of imagery, and creating stories out of facts or material that you’ve got in front of you. But your mom was talking story in a different way, accepting your own dreams as stories that your unconscious reveals to you, encouraging you to record and interpret them.

It seems like your background was heavily influenced by the thought of narrative. Obviously, you read quite a bit, too. You’ve always just been steeped in language and story and visual things.

My mom is a writer, too. She published in magazines and stuff. When I was growing up, we always used to write stories together. We’d go on a walk, and make up a story, and when we got home, we would write it down. We used to self-publish a little newspaper about stuff that was going on with us and people that we knew. Then we would give it out to all our friends. With her, too, that was a very valuable experience. That art is something you can make yourself, you don’t need permission, and you don’t need… In my case, as a child, I didn’t have any qualifications, I just had a desire to make it.

That’s great. This might seem immaterial, but I’m going to get back to the physical now, and to your red hair. [Gfrörer laughs.] Is it still very long?

I cut it a couple months ago to just past my collarbone, I guess. I never go to the salon, because I feel like I never know what to do. I don’t have a good sense of what I look like, or what I want to look like. I don’t know how to go to the salon and be like, “Oh, give me that haircut that some celebrity has, that will look good on me.” Like, I don’t know. I just let my hair grow out until it’s down to my butt, and then it’s just such a hassle I end up cutting it off, or I have some emotional issue where I’m like, “I have to get rid of all this,” and then I cut it off myself.

I feel that way, too. I have no idea what I look like.

It’s weird, right?

Yeah. It is weird. Because, you don’t — I guess you can see yourself in the mirrors, but it’s never exactly —

But it’s not the way you see other people, when you look at other people.

Exactly. You see them three-dimensionally. And you see them move, you see them express. And a mirror is a dead expression, generally.

If you don’t mind me saying so, you’re an extremely beautiful woman. I think that can fuck with your way of being in the world because that’s a thing that people deal with that they think is you, but that’s also outside of you. I think about this in old rock songs all the time. There’s this idea of this woman who’s so in control of her beauty and her seductive powers, and she uses it to get what she wants from men or whatever. And, I’m, like, “How is that a thing, though?” I heard a song on the radio, where they were like, “She’s got legs, and she knows how to use them.” How does anybody know how to use their legs? Is there really any woman who’s like, “My legs are so incredible, I’m going to use them to get a man buy me a car.” I guess people do? I wouldn’t know how.

Right. When you said whatever you said about my appearance, it’s so weird to me. I think of myself as so deformed.

Really?

Incredibly so. I have no love for my appearance. At this age, I can maybe accept it so I don’t feel embarrassed to leave the house. [Gfrörer laughs.] Because I have to teach, so I’ve learned to not even think about how I look after a certain point. I’ll put clothes on, and brush my hair, do whatever I’m going to do. But then I stop thinking about it. Because when I start thinking about it… awareness of appearance is so oppressive to me, the inside-outside thing…

It’s hard to conceptualize yourself as you appear to other people.

I’m sure, ever since you were a child, people focused on your red hair.

That’s true.

I don’t have red hair. So, no one’s going to say, “Oh, you have brown hair! Amazing. Your brown hair… ” [Gfrörer laughs.] No. Never heard it. Right? But with you, it’s almost something magical. People are fascinated by it because it is so rare. You’re the classic redhead with freckles and everything. Perfect! What do think that means to people? What has it come to mean to you?

I think there’s definitely a mythical quality about it. When you think about redheads in art, there’s a lot of pre-Raphaelites. Who are some famous redheads in history? Eleanor of Aquitaine, or Boudicca, or Lilith: witches and queens. It seems kind of magical, and maybe like mermaids, too. And also, because my hair is long, I think I have a body type that’s —

Sylph-like, yeah.

— associated with mermaids, probably. People have compared me to a mermaid, often. Men.

Did that have any influence on your work? [Laughs.]

I’m sure that it did. For a while, when I was a younger adult, I think I was really suspicious of that — it was like internalized misogyny. It felt really “girly” to me, and therefore not serious.

And yet, you were just talking a minute ago about that song. “She’s got legs, and she knows how to use them.” But mermaids have no legs, and yet, they know how to use them. And in your stories, as well, they seduce and use —

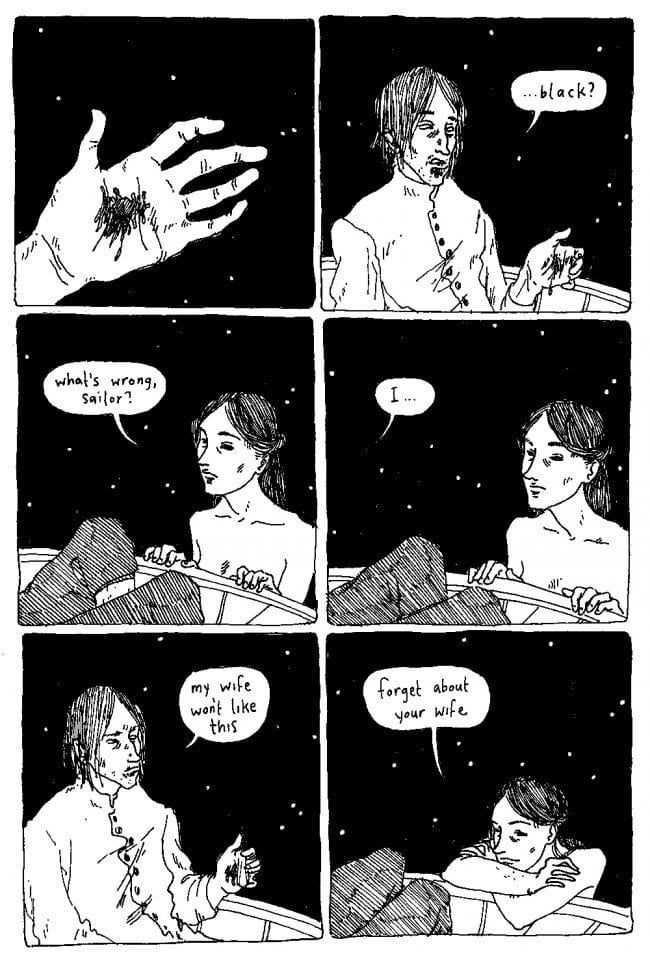

That was a huge concern to me in Black Is the Color. The idea of mermaids—normally, you get it filtered through the experience of sailors. Men who are being seduced by these mermaids. The mermaids sing to them, they comb their hair, and try to get them to crash on the cliffs. I was thinking, “What is it like to be these mermaids?” The same idea of, you’re being yourself in the world, and then, if a man finds that attractive, he’ll be like, “Oh, you’re doing this thing to me. You’re doing this so that I will respond.” But you’re just doing it because you’re doing it. So, that’s what I had them doing. They’re making music because that’s their art form, and they’re watching the ships sink because it’s entertaining to them, and not really thinking about how it affects these men. It’s secondary to them.

Exactly. It does become oppressive. Someone looking at them, perceiving them as beautiful, and seductive. But it really is in the eye of the beholder. They fail to see the mermaids as human. Well, not human, but — [laughs].

Like I was talking about with being beautiful, it’s The Man’s — I’m saying The Man because I think this especially an issue between men and women — that idealized perception of them is getting in the way of his understanding them and what they want and who they are when the man is not around.

It can be dangerous, too, if someone has seen you as this ideal, and then if you do anything to call that into question, they get angry at you.

Yeah, they get angry. Especially if you’re an artist and you have any kind of recognition at all, people will see you as this Artist who has a power. They’re not seeing you as a person. You don’t get to know people naturally. In a way, before you’ve even met them, they feel like they know everything about you.

I imagine that's especially true with you, because people read your work and they think, “Oh, this is Phoebe’s autobiography, and now I know Phoebe’s entire life story.”

Right. And they’ll even go and read interviews and things, and then I’ll meet them, and I won’t know anything about them.

That’s so weird, right? Strangers come to you, and they’re like, “Oh, well you did this, and you used to live here, and now you live there. And I know your kid’s name,” and all this stuff, and I’m like, “Who are you?”

And it so alienating. It makes you feel so strange. It makes you feel alone, like there’s no chance of — well, I guess I’m talking about myself. [Gfrörer laughs.] Here I am, single, and I’ve felt this aversion to meeting people, because it’s happened so many times. Because I have an unusual name, people look it up and know everything about me. And his name will be “Joe Smith.” [Gfrörer laughs.] There’s no way I can know who he is before I meet him, and it’s miserable. [Laughs.]

You have to date somebody else who’s famous.

Right. Where am I going to find those? Who cares! Back to your red hair.

I feel like there’s cultural baggage around redheads being very sexual, or hot tempered.

Is it baggage, or is there some truth to it?

It is just an association?

Yeah.

I don’t think of myself as an aggressive person, or a person with a temper.

But you’re intense.

As like, a virago? Am I intense?

Yeah, you’re intense. You’re very focused on what you’re speaking about.

I think that’s true. I also feel like a slow-moving person. I think slowly. I react slowly, which can be good in a crisis, because I will be someone who is not freaking out when something terrible is happening, and then the next day, I’m like, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God,” after the moment has passed.

That makes me feel bad. When we first met, and I was going all over the place. [Laughter.]

That’s okay. You shouldn’t feel bad about it.

I have a student in my comics class now who has really red hair — just like you — and freckles. Her very first story was about her red hair. I think it really did shape how people look at her. She’s the only one in her family with red hair.

Me too.

She was talking about Halloween, and she didn’t know what she wanted to be. And her impulse was to be something that had nothing to do with her red hair. She could wear a Hannah Montana wig or something. Anything. But she ended up being Pippi Longstocking.

[Laughs.] Pippi Longstocking is so interesting. I read those books when I was a kid, and I didn’t really relate to Pippi at all, because I wanted to be good and follow the rules.

Did you?! That’s interesting. See, I wouldn’t have imagined that, necessarily.

Well, I don’t know if that was adults’ experiences of me, but that was how I felt. So the idea of her being such a weirdo and really not giving a shit…

Or not even understanding the rules.

The thing about Pippi is that she’s very independent. I was thinking about this, because Anne of Green Gables is the other famous redhead girl. Anne, people don’t like her, they don’t think her hair is pretty, and she’s also like a weirdo. Her hair is a symbol how she is a weirdo and an outsider. But, because Anne is poor — Pippi’s rich, because her father is a pirate, and she’s also extremely strong. When people try to make her do things, she just tosses them out of her house, literally. Policemen come to try to take her to an orphanage, and she’s like, “Okay, I’m done with you now. You have to leave.” And she picks them up by the belt and dumps them on the sidewalk.

Right. And she is basically an orphan. Father or not.

Pippi’s father is on an island in the South Pacific.

What’s the name of her house again?

Villa Villekula. I’ve read these books over and over. My son and stepdaughter love them. I know them all by heart now.

I think I was scared, too. I didn’t want grownups to think I was rebellious. So, I would read stuff like that, and be like, “Oh, maybe I shouldn’t tell people that I read this.” I was really concerned about that. You remember the show Jem and the Holograms? It was on when I was little, in the ’80s. It was about these rock stars that were really glam. I never wanted my parents to know I was watching it. I was like, they’re going to think I’m trying to be rebellious.

That’s funny. I was thinking of you when I was thinking about what I read when I was a child. One of those things was Edgar Allan Poe. I remember, I must have been 8 or 9, when I was reading “Annabel Lee.” I was memorizing it. My aunt, who was visiting, came in and saw that I was reading that, and flipped out and told me I shouldn’t be reading that, and to put it away until I was older. She took it away from me. No one had ever done that to me before. I think it did cause me to take my reading habits underground. I got far more curious about what actually was on my parents’ bookshelves.

I remember being a kid, and sneaking around, looking for the sex scenes in books — flipping through to find the sex scenes.

I remember seeing the book Naked Lunch on the shelf. “Whoa. I've got to read that!” Just because it said “naked.” But I remember I was disappointed, because I didn’t really get it. [Laughs.]

When I was little, I was into the Phantom of the Opera, when I was 9 or 10. I don’t remember how I first encountered it, but I read the book over and over again. Somebody wrote a sequel to it, like a pulpy book, that I think was called Phantom. I finally got my dad to buy it for me at the grocery store. I read about a third of it, and then he flipped through it, and he was like, “You can’t read this.” That’s the only book that I think was ever taken away from me.

Was it because it was trash, or because of the content?

I think at one point, one of the other circus performers —the Phantom, Erik, when he’s young, he joins the circus—he gets raped by one of the other circus performers. I think that may have been what did it. I never did finish it, so I don’t know.

That segues into the question of your own children — I’m counting them as two.

I don’t have that much influence over what [my stepdaughter] Helena does, but I have some.

Do they read your work?

No. They’ve never really expressed that much interest in it. Also, I would steer them away from it. Frank, because he’ll be around when I’m working sometimes, he’ll look over my shoulder, and be like, “What’s going on here?”

How old is he now?

He’s seven. There was this point when I was drawing a book that Sean [T. Collins] and I did, called In Pace Requiescat, which is about “The Cask of Amontillado”.

I love that story.

The guys, they have sex before he finishes the wall.

That was great.

Frank happened to come in, and I didn’t hear him come in, and he saw me working on this page where the guy is sucking the other guy’s dick. But you could really only see the dick sticking out of the wall. He was like, “What’s happening in that comic? What is that guy doing?” He was like, four or something. I just closed it. I was like, “Frank, I don’t want to talk about it right now.” [Gloeckner laughs.] He goes, “I know what he’s doing. He’s eating a hot dog.” I was like, “Yeah. Yeah, exactly.” I didn’t really discuss it. [Gloeckner laughs.]

There was one thing. In Black Is the Color, there’s a scene where the mermaid breastfeeds the sailor, and her milk is black, and he spits it out in his hand. I did show that to him, because somebody had read it, and been like, “I don’t understand what’s going on here.” So, I showed Frank that scene, and I was like, “Okay, Frank. Can you look at this, and tell me what’s going on here?” He was like, “Oh, she’s nursing him.” ’Cause he was just a baby, you know. I was like, “Okay, my baby son understood this, so adults should be able to understand it.”

Did you get to the part where he was spitting out the black milk?

Yeah.

And did he say, “What is she doing, what is he doing?”

I don’t remember what his response was to that. But I haven’t really talked about sex with him. He hasn’t interested, or he hasn’t asked me questions about it. I think he has a vague idea about it. And even if I did, I don’t think I’d show him my work and be like, “Oh, this is how people have sex.” [Gloeckner laughs.] The sex in my work is kind of pathological. That’s like a 201 class.

It is and it isn’t. The actual sex, oftentimes, seems incredibly regular. Right?

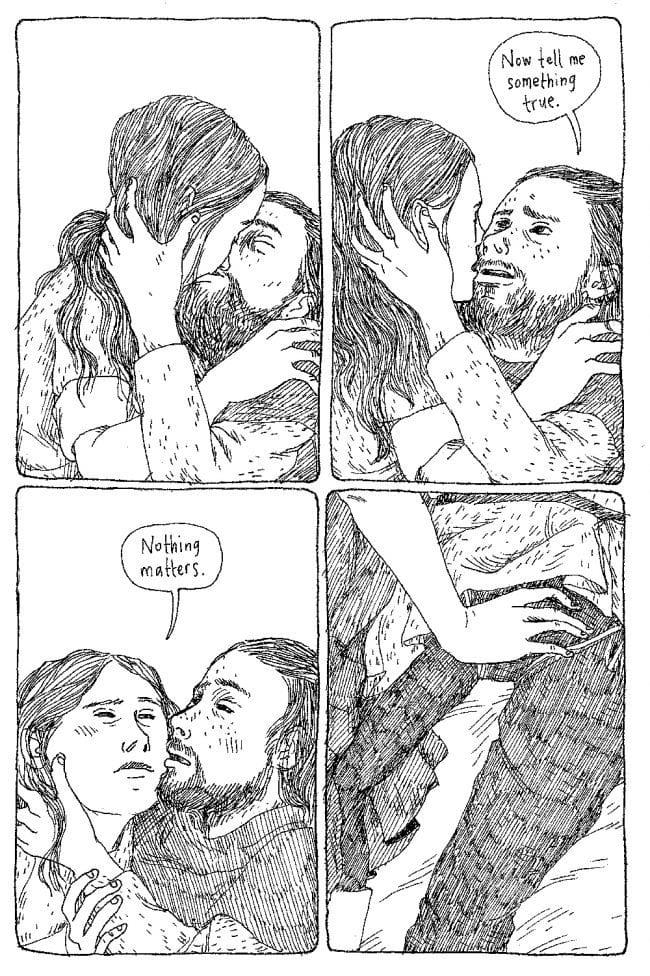

Yeah. Like in Laid Waste, I think the sex is really normal.

In a sense, yeah, you could show that to someone and say, “This is what sexual intercourse is.” It’s the psychological stuff that makes it complex and very real, in a sense.

I think the way I depict sex oftentimes is very normal, as a normal thing that people do, as an expression of emotion or because it’s fun or whatever. I think it’s better than if I were only thinking about it as porn, and what’s going to be the hottest thing.

Sex is a very powerful element in your stories. The sex feels like just as much an integral part of the story as psychological and magical elements. They all work together to give you this — I feel speechless, sometimes, at the end of reading a story by you. But it feels complete. Sometimes I don’t even remember everything that happened, but I’m remembering this feeling of both despair and elevation. It’s kind of addictive. You’re able to make me feel that again and again. I’m not a very articulate critic of “literacha,” comic or otherwise, but my response to it, is, I just feel like, “Wow,” after I read your work.

That’s good. [Laughter.] Sometimes when people write reviews, they say it’s like getting punched in the face or something. So, that’s good.

More the stomach. You don’t particularly exaggerate penis size. Just as your female characters are always very thin, and don’t have big boobs, the men also are very normal proportioned. Kind of on the wimpy side. But their parts are all functioning —

A big penis is not part of what’s interesting to me in sex. I’m interested in penises, for sure. Looking at penises is sexy to me. But, if I’m trying to visualize a scenario that’s sexy to me, a huge dick is not necessarily part of it. That just seems boring.

Why is a big dick more boring than a small dick?

Why is a big dick more boring than a small dick?

I don’t think I made them abnormally small, either. The body is just the body. What’s interesting to me isn’t the physical qualities of the particular person, but the meta-narrative, emotionally, what’s happening. What do these acts mean as opposed to what does it mean to have this body shape? I’m interested in, what does it mean to behave this way, more than, what does it mean to look this way?

I think more about body variation with women than with men, because it’s important for women who don’t have whatever is the idealized type of body to be represented.

But you’re not drawing fat women.

I know. But I wish that I would.

And you’re not drawing fat men, which is something that both men and women have to deal with.

I should and I just don’t. It never comes out that way. I feel bad about it.

The bodies seem almost as neutral, sexually, as you can make them. [Gfrörer laughs.] The sex scenes are so graphic. I’m just wondering how those two things fit together. Well, it’s clear how they fit together [Gfrörer laughs], when they fit together.

Well, the thing goes in the thing, and —

That’s very clear. I think that maybe one day, you can show your illustrations, your comics, to your son.

[Laughs.] When he’s older.

The general neutrality of their appearance makes it seem all the more normal. You could project anything onto those people.

This gets back to what to what we were talking about earlier, about how you don’t have a perception of yourself as a unique individual. To you, you’re the default, and everyone else is some weird variation on that.

Right, and interesting, therefore.

The idea that the neutral body is a thin, white body. That’s very political.

It is.

There is no neutral default body.

There is none.

That’s culturally constructed as the default.

But it feels like, in your work, like you’re neutralizing those bodies, somehow.

Yeah. Because that’s my relationship to it. That’s the body that I have. It feels neutral to me. It’s not something that I have moved outside of, because I feel so consumed by the puzzle of my own body.

If it feels neutral to you because you’re housed in the same sort of casing as your characters, then does that subtract the political meaning from it? That’s what artists do. They project themselves —

I think the political action in my work is that I want to show women as actors, rather than a receptive or decorative object.

You do it in such a way that it’s not like that song you mentioned—“She's got legs, and she knows how to use them.” You’re not saying, like, “Yeah! Some women have spunk, and they can do this, and we should all be like that.” You’re not saying that at all. Women do typically climb on top of men and have sex. All of those things. And it’s not because they’re sexual demons or succubi. It’s because that’s human nature.

What’s on your shirt?

This is the CAB [Comic Arts Brooklyn] T-shirt that Dame Darcy drew.

What do you think of Dame Darcy? Is she an inspiration at all?

I really like her work a lot. I was talking about this with my friend Hazel [Newlevant] this weekend. I’m glad that I don’t — I worry about setting myself up by having some kind of a persona. It seems like it’s really hard work to be Dame Darcy. Do you know what I mean?

You talked the other day about developing your brand, and how difficult that was. I’ve never thought too much of “branding” myself, honestly, but I can see that it is becoming more and more important… (Oh, you look lovely. I’m going to have to take a picture of you in good light.) Artistically, there are some stylistic similarities between you and Dame Darcy. I don’t think of you as having a persona that’s as tightly packaged as that at all.

I love her illustration style. I really love her drawings and I like — it feels like her work is very girly. Most of the men that I know who read comics haven’t read her work because there’s something about it that’s off-putting to them. Like there’s a lot of bows and sparkles and fancy dresses, and they’re like, “Oh, ew.” And I like that. I like that it’s really aggressively feminine.

But I’m just curious for my own purposes what you think of her stories? Are your connections to Dame Darcy’s work more than superficial? I guess I’m struggling to tie you to someone whose shirt you're wearing…

No, I mean I haven’t really read that much of her work. I have a handful of Meat Cakes. I haven’t read everything. And I hadn’t really read it until I was older so I don’t know if I could say how much she’s an influence on my work, but probably some.

Are you saying that only works that you read at a certain time were bound to have influence on you? And what time was that?

I think that my illustration, or the aesthetics of my work, were pretty set before then, but I guess stuff still influences me.

When do you think your tastes were set? And what do you remember reading or seeing that —

I think when I was in college. I was really into German and Austrian Expressionism. I really loved Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, and Otto Dix a lot. And Kathe Kollwitz is still one of my favorites.

So, in college — that’s where you can recall all the influences bumping about, and influencing what was to become your style?

Yeah, I don’t think that my work ended up looking much like that, though.

No, but it definitely shares a spirit. When you say you’re influenced by those artists I’m not surprised at all.

I really liked pre-Raphaelite art, too. When I was younger, in high school, I did. And Victorian or Golden Age illustrators: I liked Maxfield Parrish. I loved Aubrey Beardsley. And Maurice Sendak — we always had a lot of Sendak books when I was a kid.

So there’s different stages in your life, where art of different sorts influenced you, somehow, or interested you.

Yeah. But I was never a big comics reader.

I wasn’t either, actually. That’s interesting. Do you remember: what was the first comics story that you ever published, yourself, or maybe someone else? What was that?

When I was in college, I took a comics class taught by Ellen Forney. So, for a project, I made a minicomic. It was an adaptation of a story from the Little Flowers of St. Francis. I don’t remember which one it was now. I probably still have a copy of it, but I have avoided reading it, because I think it’s really bad. The drawings look really bad and stupid to me. There’s something really earnest about it that’s embarrassing to me now. [Gloeckner laughs.] I still really value earnestness, but it’s un-self-aware.

That’s kind of sweet, actually. I would love to see it, the way you describe it.

Oh, God. It’s so embarrassing.

Julia’s young earnestness.

I made a bunch of copies of it, and I wanted to sell them, the way I had used to sell my zines when I was in high school. So, I went to this coffee shop called Joe Bar that everybody used to go to, that was right up the block from the school. They said they would consign it. I gave them all my copies to consign. The next time I went there, they were gone, and they were like, “We don’t know what you’re talking about.” [Laughs.]

[Sympathetically]: Oh, you’re kidding.

No.

So, you don’t know if they actually sold them, or just stuck them somewhere.

No. Maybe they lost them? I have no idea what happened to them.

That’s disappointing.

In retrospect, I can’t imagine why a coffee shop would want to consign thirty copies of my stupid St. Francis comic [laughs].

Hopefully they sold them, and they exist somewhere.

No. I think they’re bad. I think nobody should see them.

I think you should send me a copy.

If I find one, you can have it.

I know you know where it is. You must.

I’m pretty sure I have one in a box with my old stuff at my mother’s house. I might have a couple.

I really would like to see it. Whether for this or not.

Let’s just talk about the future, then. I actually wrote out these questions, where I didn’t before.

All right!

Your stories stand on their own, solidly. But collected, the effect is overwhelmingly dark, visceral, haunting. Collected, they’re amplified. They read together really well, but they can also stand on their own. I’m just trying to imagine what kind of longer work you might do? You’ve become kind of a master of the short form. I was wondering if you’ve entertained the idea of doing a long, novel-length book?

I really would like to. When I was younger, I did this book Flesh and Bone, in 2010. Dylan Williams, who published it, was like, “Okay. I need you to make it at least forty pages long.” I was like, “Oh, my God. That’s so long.” It was really a struggle for me. Since then, I’ve done a few things that are that long. It seems easy to me now, and my two longer books are about eighty pages long. I would like to be able to make still-longer work as I get older and more comfortable with my writing. I don’t want to push it or force it. I know my publisher would like to have something longer from me. [Gloeckner laughs.] I know that it can feel like a longer, more substantial book is taken more seriously.

Not necessarily. I think some authors have built bodies of work on shorter pieces — like Edgar Allan Poe, for example.

I agree with that. I guess I’m thinking more from a marketing perspective.

Even Robert Crumb — Genesis can be considered —

But that just came out.

His whole life, it’s a string of short things.

Yeah. But after finishing a story, I think about the story I could have done; different parts of the story I could have continued with. In Laid Waste, one of the last things that I wrote was the scene — the main male character, his name is Giles. He has a bunch of daughters and they’re hanging out together. Their mother has just died, and one of them is milking the cows. That was the last scene that I wrote. Afterward, I felt like I could have done a lot more with them. I would have been interested to write more about what they ended up doing.

I remember wondering about them at the end of that story.

That’s the only time you see them. You see the little one, Mariette, at the beginning, with her father — later, her father’s off doing some shit, and her sisters are looking after her. I would have liked to see more of them.

I don’t think the way you finished the book would prevent you from continuing it.

I could really add more and more minute scenes into the edges of the story. Right now, I’m working on a sequel to Flesh and Bone that’s already written. I’m in the process of inking it now. Originally, I hadn’t planned to make it a series, but I got to thinking about it, and more stuff that could happen with those characters.

How long is this book going to be?

It’s the same length as the first one. I’ll publish it in Island, probably — Brandon Graham’s magazine that he publishes through Image.

You’ll publish it as a book, not in the magazine?

I’m going to publish it in the magazine first.

Serialized, or all at once?

I’m not sure. I think he would let me do it either way. But I want to publish it in the magazine first, because I’ll get paid for it.

Oh, great. You just said that you’re working on the drawings; you have it all written. Is that your typical process? Do you write the whole thing out? Do you script it? What do you do?

I thumbnail and script it at the same time. And then pencil it and ink it, so it’s all penciled now, and I’m just inking.

You generally do it in different passes. It general, you have the whole thing worked out, and then you return to the beginning, and start inking, and so on?

Yeah. Usually I’ll kind of jump around. I won’t do it straight from beginning to end, but I’ll do whatever part I feel like doing. If I’m feeling not super into it, I’ll ink a page or draw a page that I feel like is going to be fun or easy — when there’s not a lot happening in it. In this Flesh and Bone sequel, yesterday, I was feeling unmotivated, and there’s a page where the witch is spinning with a drop spindle. And then the thread gets tangled, it does that thing where it twists in on itself and makes a tangle. That was really easy to draw, it was just several panels of thread spinning and then tangling up. It went really quick, and I was like, this is really motivational. It was like: BAM, I finished a page.

You got into the swing of things.

Another question I had is about collaboration. Amongst your collaborations — and I don’t know all of them — I’m thinking of the work you did with Sean, and they were adaptations of Poe stories. That was just something I would just expect you to do on your own. I would totally trust whatever you would come up with, your interpretation. I’m wondering: why the collaboration, and how did that change your work?

The porn adaptations of Poe, that was Sean’s idea. He sent me the script for the first one [In Pace Requiescat] before we really had a relationship. He just knew my work.

[Laughs.] That’s very seductive.

I know. [Laughter.] I read it, and when I realized what was going to happen in it — at first I was like, “Who does this guy think he is?” To try to improve on Poe seems like a gutsy move. When I finished reading it, I was like, “This is amazing.” I was really into it. I did end up drawing it. Then, it just became a thing we do for fun. I don’t usually collaborate with people. I drew some stuff for Anne Elizabeth Moore for a magazine but she hired me to do it. With Sean, I really like his writing, I think he has a good sense of what is going to be good for me to draw: what I’m going to enjoy drawing, and what’s going to look good drawn by me. We’ve done a couple Poe/porn books. We did a comic called Hiders, which was just a four-page one about these two young women who turn into werewolves together. But they don’t talk about it when they’re both human.

It’s almost like they don’t acknowledge it to each other?

Yeah. They just pretend like they don’t know what’s going on. They just see that some people got killed, and they’re like, “Huh. That’s weird.”

We did one called The Deep Ones that was about why water is scary, or why the ocean is scary. Why are there sea monsters? Is that trope —

I think I have that one as well.

That came out of some conversations we had had. The Deep Ones and Hiders, both of those, we ended up doing because I wanted to do a comic for a certain anthology, or something, but I didn’t have an idea. And I was like, “Do you have an idea? Can you write a script for me?” And so he did.

How much do you have to pay him?

He wouldn’t take any money for it. He was like, “No, no.”

It’s funny that you describe those stories as “porn.”

Yeah. They’re not exactly —

It never even occurred to me to classify them that way. Can you explain?

They are stories about fucking. I think they’re sexy. I get turned on when I read them. Maybe I’m used to them now, but, at some point, I did.

I’m asking this because the definition of porn is kind of mushy. Those stories seem so psychological and the sex seems like a natural expression of something. I felt such an empathy for the character [in The Hideous Dropping Off of the Veil, based on “The Fall of the House of Usher”], the dead girl who comes back and fucks a guy.

Madeline Usher is a very relatable character for a character that never speaks.

It never even occurred to me to call it “porn.” It seemed to be all of a piece. There was a reason for it, and it was all tied into the mind and everything else. It seemed quite complete and not sex for sex’s sake.

I think that we looked at the original story, and what the psychological and emotional state of the characters are. In both of those stories, and in a lot of horror stories, when the people are doing something awful, it’s because there’s some other, unaddressed thing that they’re trying to …

Resolve?

Get rid of. That was what we were working with. Where’s the tension in the story? What if that tension was addressed through sex? What if sex was part of the conversation that they have in the story? In the original story, “The Fall of the House of Usher”, Roderick Usher, his sister dies, and he gets his friend to help him bury her under the house. He admits to his friend — they hear her breaking out of the tomb — that she was alive when they buried her. Then she breaks into the room and pounces on him, and he dies of fright. She dies from the exertion. The friend runs out of the house as it spontaneously collapses. She’s furious about having been buried.

She comes back, in your version, as the angry virgin. The adolescent, or young woman, who was on the precipice of being able to express any libidinous feelings, but… And her brother, whatever relationship they had — that whole sexual energy and regret, and fear — it all comes and out is expressed sexually, but death is always just around the corner. It’s death and sex. It’s fantastic.When you said porn, it just startled me because it just didn’t occur to me. And, yeah, it is kind of sexy, but I don’t think that’s the definition of porn. If it turns you on, is it porn? I don’t know. That’s like saying, “Oh, she’s wearing a sexy outfit. She must want it.” You can react sexually to anything. If your cat is warm in your lap and you’re like, “Oooh, I feel warm down there…”

I don’t know if regular porn is that interesting to me. Sometimes it is. For me, if I’m making something to be turned on by, I want to create some kind of emotional stakes.

Yeah, tension.

In this case, it’s essentially fanfic. It’s the same thing people do when they write a story about what if these two characters from Game of Thrones had had sex in this scene.

That’s an interesting thought. I guess so. I think you only have about ten minutes, right? You have to leave soon. Two quick questions to wrap up.

Okay.

What do you think happens to us after we die? [Gfrörer laughs.] Seriously. Can you tell me please. So I know.

Yeah. What happens to us after we die?

Our house falls down.

Yes. I don’t know what happens to us after we die. I don’t think about it. I think about the moment of death. I think that it must be a relief. I think that once you know that you’re doing to die, it probably feels good to just let go.

If you have a chance. If your head is squashed by a one-ton…

[Laughs.] If you don’t have a moment to think about it, I guess not. If you suddenly get blown up by an atom bomb, then probably that’s frightening. But maybe you don’t even notice.

But if you’re going down in a plane and have advance notice. That must be…

I think probably first you feel panic, but at some point you feel calm. Maybe? I don’t know.

After you’ve struggled with your phone, and turn it on to text “I love you” to your son, or whatever.

Oh, God. Yeah, I suppose so. I did a comic where I was killed by some malevolent spirit that I offended by accident. I become kind of a ghost or a wraith-like creature. One of the things that I say in the comic is, “This is great. I feel really good about myself right now.” I talk about all the things that I can do now that I’m dead and one of them is that I never have to pay my student loans back. Do you ever have that thing when someone cancels plans with you — like you’re supposed to go out, but then they can’t — and you’re like, “Yes!”

Yes! Yes! But you’re afraid to decline in the first place or cancel it yourself.

Yeah. Maybe there’s a part of you that’s like, “Now I don’t have to do that job interview on Monday,” or whatever.

Right. [Laughs.]

I think after you die — nothing. Your consciousness disappears into the whirling void. Or maybe becomes part of a larger consciousness.

Maybe.

I think that you forget your identity. I think you no longer have the identity that you had in your life.

Okay. Good answer. [Laughter.] I guess on a lighter note, perhaps, I’m wondering about your relationship with your son. He’s 7?

Uh-huh.

Your parents were a psychologist and a filmmaker. How do you see him? Do you have any notions of what he might be good at or ideas of where you see him the future? And if you see him as someone creative, how do you encourage that?

He loves to draw. He draws constantly. He’s really smart and funny. He makes up a lot of stories and I can tell he makes up more stories that he doesn’t want to talk about that are private to him, that maybe have a lot of power that he doesn’t want to ruin by sharing. I’ll tell you a story about Frank. I hope he doesn’t find out later that I told you and get mad. A couple years ago — I guess he was in kindergarten — he had a crush on a little girl. She had red hair like me. Somehow he found out that she liked him too, so she was his “girlfriend” for a day or two. Then she broke up with him because she also liked this famous hockey player and she was going to marry this hockey player.

[Gloeckner laughs.] He was really devastated by this. And, of course, it was so awful to see his tiny heartbreak. Anyway, he drew a picture that day of a monster — kind of a terrible monster — and he told me he was going to bring it to her as a present. I was like, “Oh Frank, that’s really nice.” But then I was like, “Wait. Are you giving this to her because you want to make her happy by giving her a gift, or do you want to give it to her because you want to frighten her or upset her with this monster?” He was like, “I need to give her this so that she can understand how she made me feel.”

Mmm. The monster itself — did it have an emotion?

It looked angry.

So that’s how he felt? Angry. Or at least he wanted to express that to her.

I told him, you can’t give her a drawing because you want to upset her. That’s not okay. When he told me that, I was like, all right, he has the cartoonist’s instincts. The thing where I can’t talk about this, but I’m going to draw a picture that will make you feel like I feel.

That’s absolutely true and that’s oftentimes the power you feel in comics. It does give you a feeling that you have control over your life and your history. It’s amazing. And sometimes you do use it in that magical way … I’ve drawn characters that are reprehensible and then given them the names of people who have really pissed me off. [Laughter.] No one knows it except me.

Do you like it when people tell you that your comics have upset them? If someone says that your comic made them cry, it feels good, right?

Someone I don't know?

Yeah.

Yeah! Yeah, it does. One time, this small-town politician who was running for some office in California — one of my books was banned because a kid had picked it up. A Child's Life. In his stump speech, he held the book up and said that this book was a “handbook for pedophiles.” And he got it out of the library!

Nice. [Laughter.]

A handbook for pedophiles? I mean… [Laughter.] I was happy.

That’s great. I think that’s very cool. Fuck that guy, also.

Right, but still! It was so dramatic, that it made me feel very powerful. I pitied him for his misunderstanding of my work … and probably life in general.

Every time someone says something like, “Your book ruined my day.” I’m like, “That’s right.”

Score! [Laughter.]