“Emil Ferris is one of the most important comics artists of our time.”

“Emil Ferris is one of the most important comics artists of our time.”

- Art Spiegelman, quoted in The New York Times ("First, Emil Ferris Was Paralyzed. Then Her Book Got Lost at Sea." by Dana Jennings)

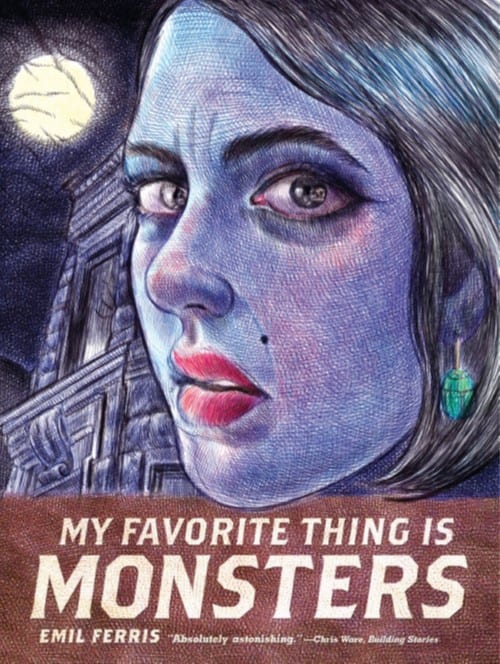

A reclusive person, Emil Ferris, author of the just-released breakthrough graphic novel, My Favorite Thing is Monsters (Fantagraphics, 2017), has not allowed much personal information out in the world. This is her first long form interview.

In my earlier review of Monsters, I wrote: “The author, one Emil Ferris, seemingly arrives from nowhere to join the ranks of graphic storytellers of the first order.” A single mother who has supported herself for many years as an artist-for-hire, including designing McDonald’s toys and working in animated films, Ferris has developed a complex visual-verbal style that is at once extremely refined and highly personal and used it to create her first published work., thrilling in its artistry.

In this interview, conducted February 7-10 2017 in several Internet chat sessions and additional rounds in email, Ferris challenges a lot of labels, putting them in quotation marks. This is a telling detail about the outsider stance of this author-artist. My Favorite Thing is Monsters similarly challenges commonly held preconceptions, including how a graphic novel should look and work. In conversation with her it becomes clear Monsters is new and different because Ferris, a gifted artist, is approaching comics and graphic novels from an offbeat, hard-fought viewpoint.

Part one of this two-part interview covers Ferris’ background, her life as an artist and her love of monsters.

Paul Tumey: First off, let me thank you for this interview, Emil. After I read My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, Book One, I was intensely curious about you and your novel.

Emil Ferris: I'm glad to be talking with you, Paul.

Paul Tumey: You’ve had quite a journey with this book and, as I understand it, your life to date. Why don’t we start with you and your early years? My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is set in 1960s Chicago. Is that autobiographical?

Emil Ferris: Yes, I was born in Chicago but my parents left here when I was around a year old and, when I was five or so, after living in Albuquerque New Mexico and Santa Fe my father―a dyed in the wool Chicagoan - moved us back here to a low income building in Uptown.

Paul Tumey: Were your parents artists?

Emil Ferris: My parents met as two hippie art students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. My mother described offering to "Clean his brushes, if he would stretch her canvas..."

Paul Tumey: Have you always been a visual artist? Did it begin for you as a child?

Emil Ferris: It began with Lil' Abner actually!

Paul Tumey: A Tribune comic from 1964 to 1977, when you were growing up in Chicago. Of course, it got started before that, in 1934 I think. Tell me about that, please.

Emil Ferris: My mother, an artist herself, kept me busy by giving me the strip cut out from the paper when I was about two years old. I could not walk until I was closer to three years old, due to having scoliosis, but I began to draw very early. She said at two I began very carefully copying the characters from the strip and she said my drawing at two surprised her because it was so exacting.

Paul Tumey: So you were drawing before you were walking. And it seems comics got into your blood at an early age. Did you read much comics growing up?

Emil Ferris: Mad was my oasis. It was so defiant and contentious and it demanded that the social structure be questioned and that it explain itself!

Paul Tumey: Li'l Abner had a lot of satire in it, too.

Emil Ferris: Looking back, I realize that it did. At the time, I was just enamored by the concise drawing style and by emotions caught in a few scritch-scratches made by a quill pen.

Paul Tumey: Were the adults in your childhood years questioning social structure? What were your parents like when you were a child?

Emil Ferris: My father was the child of an immigrant who became the tailor, dressmaker and furrier for a lot of wealthy famous people. My grandfather had a furrier shop only blocks away from the “murder castle” of H.H. Holmes and was here through the “Devil in the White City” period. My grandfather paid his (required) protection money to Al Capone - and I understand he liked him - calling the young Capone, “a nice young man.” Apparently, he preferred to pay protection money to Capone than the Chicago Police. So in this story I'm telling you that my father―who loved history and was something of a philosopher―understood that the world was not a place of blacks and whites but a much more inscrutable and complex place.

Paul Tumey: Can you share a little about your background?

Emil Ferris: My mother is descended from indigenous Mexican people, German, French and Irish emigres and the Sephardic Crypto Jews of New Mexico, who fled the Spanish Inquisition and ended up there in the early 1600s.

Paul Tumey: What a rich heritage. I was in a thrift store yesterday, and I found this collection of poems and prose by Robert Frost. I opened the book at random and read this passage of words spoken by Frost in a 1923 interview:

"America means certain things to people who come here. It means the Declaration of Independence, it means Washington, it means Lincoln, it means Emerson―never forget Emerson―it means the English language, which is not the language that is spoken in England or her provinces. Just as soon as the alien gets all that―and it may take two or three generations―he is as much an American as the man who can boast of nine generations of American forebears. He gets the tone of America, and as soon as there is tone there is poetry."

I think this helps me get at why your book is so rich and works on so many levels. In part it may be the immigrant experiences that happened close enough to our own time they still swirl around and influence us. The courage and desire to make something of one’s life with hard work is an inspiring example.

Emil Ferris: My maternal grandparents were both very invested in what they world have described as the American ideal of service―a life as a service. My grandfather, who became the Chief Justice of the Appellate Court of New Mexico, was a Spanish-speaking man who attended the University of Chicago and was proud of his Mexican heritage. He worked tirelessly on behalf of the less fortunate. Currently, these disparaging, fallacious things―that some people feel “empowered” to spout off about regarding people of color―really piss me off. When this country is beautiful and strong, it is so because of the genius and nobility of people from many and varied places. That should be celebrated. It should be something of which we’re all proud.

We should be in the service of protecting freedom. People are not our enemies. Fear and ignorance are our enemies. While I was making the book, I thought a lot about how works like Maus, Fun Home, Jimmy Corrigan and others, really set me free. There are so many great books within the graphic “canon” that are situated firmly in that ideology of service. I drew and drew and truly hoped that what I did would inspire others to tell their stories, to really believe in them and honor them.

Paul Tumey: I would be surprised if Monsters doesn’t inspire others to tell their own stories. I know it’s inspired me. I have admired Spiegelman, Bechdel and Ware for having the courage to tackle the Important Stuff, perhaps out of a sense of service. There's a photo of Art Spiegelman during the time he was working on Maus and his shape had temporarily shifted -- he looks very dark and full of shadows -- and no wonder, considering the history of vileness and suffering he was processing to make Maus. Perhaps he went back in time and deep inside, to a dark place.

Emil Ferris: That's interesting to me. The way we manifest these emotional storms that are inside of us. I worked myself into some dark places as I wrote the story and then very pointedly I drew while in that state, as an experiment, and hoping that the lines would congeal into a torrid emotional sub-statement. Something perceivable to one's base or core, reaching the viewer on a subliminal level.

Paul Tumey: Is that when you developed the graphic style using layers of thin lines to define forms and space and to also create emotional tone? It works on a subliminal level, directing both the eye and the emotional response.

Emil Ferris: I'd been using that technique when working with pen and ink and I knew that Deeze taught Karen these techniques and she was willingly bastardizing them by drawing in Bic pen. But in terms of actually being sad, angry and afraid when I drew: that was the experiment.

Paul Tumey: How long have you had that remarkable graphic style -- how far back does it go?

Emil Ferris: I think I really started developing that style when I was about eight.

Paul Tumey: And I agree―a flashy style with substance isn't worth much, I think―facing off with the difficult feelings is what gives the whole enterprise depth. I feel that when I read Monsters. That pulled me through the narrative as much as plot. You can see artists getting into that space and producing work of remarkable depth and complexity, and then backing off from it, perhaps out of survival. It seems very intense and consuming ... although the work that can come from that state can bring rewards.

Emil Ferris: I agree. I think that's the sacred geometry, if you will, that makes theater cathartic. The capacity we have to feel an emotional state and move through it towards empathy and understanding and yet have it all be 'fictional' 'play-acting' and thereby safe. The artist is a willing servant to those altered states and a shamanic being taking us down a dark path, meanwhile punching holes into the tunnel to allow us light and hope and a view as we travel that dark passage. That view is sometimes a page, a scene, a moment of film or a painting, poetry, music, dance, vision.

Paul Tumey: That shamanic journey, the transformation of one’s self and life, is captured with sensitivity and vision at several key points in Book One of Monsters. I’m thinking of Karen's shift into werewolf mode and later, her psychedelic trip in the graveyard at night.

Emil Ferris: As unlikely as it is, there is some truth to that graveyard tripping scene. When I was a kid I belonged to the Marble Cake Kids, a little theatrical troupe of children of many different races run by two counterculture mavens called Leo and Mila. The troupe had their base at Hull House on Beacon Street, only a stone's throw from Chicago’s infamous Graceland Cemetery. So necessarily as a kid obsessed with monsters, I decided I needed to sneak into Graceland and wait for wonders. When I was finally able to get into the cemetery, the actual wonders were the graves of famous Chicagoans whose stories I researched as I got older. There was also a ghost child rumored to live in the cemetery who I desperately wanted (and still want) to appear to me and befriend me. As for the marijuana connection, that occurred after I was a bit older, when imbibing of the weed and going into cemeteries became a pastime of mine.

Paul Tumey: I see you put the iconic "Eternal Silence" monument that is at the Graceland Cemetery into that scene in Monsters.

Emil Ferris: Yes, and there will be others in Book Two.

Paul Tumey: So you were, like your character of Karen Reyes, a young girl obsessed with monsters?

Emil Ferris: Very much so. Monsters consumed all my thinking. Monsters, art. Dickens and the questions I had about my sexual identity.

Paul Tumey: Your novel makes me want to go watch old B-movie horror films, especially The Wolf Man, which I’ve never seen. The 1941 one, with Lon Chaney, Jr.

Emil Ferris: I find it interesting that the U.S. release date of the movie, December 9th, 1941, is bracketed between the first executions at Chelmno (December 8th 1941) and the German Declaration of war on the United States (December 11th 1941)

Paul Tumey: Really? Another case of highly symbolic timing.

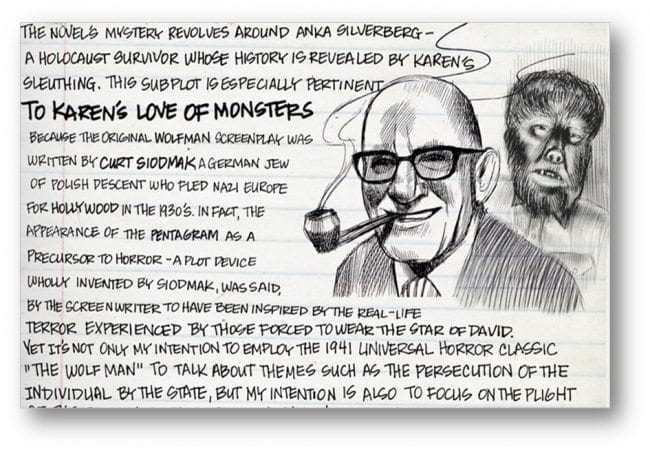

(copyright 2017 Emil Ferris, used with permission)

Emil Ferris: The screenwriter is Curt Siodmak, a Jew who fled the Nazis. Pay close attention to the pentagram scenes, those were Siodmak’s. They work within the plot very much like the labeling with the Star of David foreshadowed doom in Nazi Germany.

Paul Tumey: I just read an interview with Siodmak. I'm very interested in his work.

Emil Ferris: Me, too. I did a whole teeny graphic novelized bio of him as part of the sales package for the book - to contextualize the book.

Paul Tumey: Siodmak wrote I Walked With A Zombie, one of my favorite films.

Emil Ferris: No, I know! I loved that movie. I have it.

Paul Tumey: I have it, too. I have the whole Val Lewton set!

Emil Ferris: Me too! Val was tops.

Paul Tumey: How did you get into monsters as a kid? Did you read Creepy and Eerie?

Emil Ferris: I did. But I discovered them later. When we moved to Chicago I began watching Creature Features which was a show that aired B-movie horror at 10pm on Saturday nights. That became the central focus of my life. But, I will say I was primed to love monsters via an early childhood in New Mexico.

Paul Tumey: Why is that? Are there monsters in New Mexico? I've never been.

Emil Ferris: The Penitente art of New Mexico, featuring Death Carts and the traditional Retablos. I remember my grandmother taking me to Sanctuario de Chimayo and I remember passing a cemetery built and decorated by local people. The saints -guardians at the gates - were very menacing. Their bodies were those of manikins, their haloes were bicycle wheels, the sun was setting - it was that beautiful glowing radioactive type that was due to the nuclear testing - gorgeous New Mexican sunset and I knew these saints, these badass guardians were the “Golems” of the town and that they meant business.

Emil Ferris: Terror is beautiful in New Mexico. It is very beautiful.

Paul Tumey: Why do you think you resonated so much with the B-movie monsters? What was it about them that captivated and consumed?

Emil Ferris: When I was suddenly exposed to the Wolf Man, Dracula (and his gorgeous Brides) and Frankenstein, I would weep for them. Their lives were so tortured and yet they were so forlorn and beautiful like New Mexico, like outsiders, like the people I loved most.

Paul Tumey: So you see the monster-figure as an outcast?

Emil Ferris: Well usually that is what the monster is. Although I make a distinction between good monsters―those that can't help being different―and rotten monsters (not sure they even deserve to be called the sacred “m” word, truly) those people whose behavior is designed around objectives of control and subjugation. I don't really think they deserve the title of monster. In my mind that's an honorable title. It represents struggle and wisdom bought at a high, painful price.

Paul Tumey: It seems to me both categories of people are represented in your novel.

Emil Ferris: I remember a woman calling a Vietnam Vet a “monster.” And I remember thinking―because I had a friend whose brother came back utterly transformed by the experience of his service―that if he was a monster it was because he'd been broken and reformed in new and terrible ways and why would that be laid at his doorstep? Could it be laid at Larry Talbot's doorstep? We are the receivers throughout a lot of life. We receive so much from the larger world and what light we are shown is all we have to make more light within. It's understandable to me, this tremendous rate of suicide, homelessness and addiction among the returning vets of our most recent wars. The book was crafted with them in mind, too.

Paul Tumey: In your novel, you mix it all up. No one is all good or all bad. Schutz, for example, seems to be, well, pretty evil. He’s a Nazi collaborator and does S&M scenes with child prostitutes. However, he is generous and helpful to Anka when he doesn’t need to be. He’s sort of her “Schindler.” The "scenes" they play out are very complex; they are not black and white at all.

Emil Ferris: Yes, so many times we look at a life and judge it, but the good that people do is often sidelong with cruelty born out of terrible provoking need. Like monsters, we are creatures motivated by hunger. But also, like monsters, we are capable of mercy and love.

Paul Tumey: That's a compassionate and balanced view. One thing I realize that needs to be said is that My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is not a "creature feature" in the sense that it offers horror and fear of these beings. When I look at Karen's "copies" of the monster mag covers, I don’t feel dread or revulsion -- instead I am fascinated by the beauty of the images and how you’ve drawn them. Later, when I learned about Anka used as a child prostitute, that’s when I felt revulsion and horror.

Emil Ferris: We are the monsters. Yes, I believe we are and I'm not unhappy to be aware of this fact.

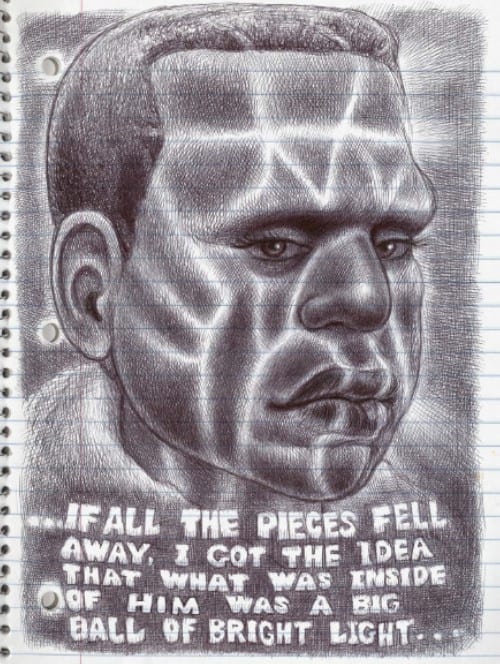

Paul Tumey: It seems to me your visual treatment of Franklin, who has a horribly scarred face, and whose name and form evokes the Frankenstein monster, captures this. At one point, you drew Karen imagining him with a radiant inner light shining out through his scars, a core of goodness.

Emil Ferris: I think there are things that happen to people that ennoble them - should their choice be for that. That does make one see tragedy as being a kind of honor.

Paul Tumey: Do you think the ennobling comes from victims choosing not to pass on the suffering to others in an attempt to help themselves feel better?

Emil Ferris: I think that would be part of it, sure. That there is something ennobling, empathic about choosing not to pass cruelty on but there is this other thing, too. I'm thinking of people whom I've known who were broken by life and then engaged to re-form themselves (and this is the heart of the monster ideology to me) in order to be more extraordinary and more powerful within themselves.

Paul Tumey: A transformation, or a transmuting.

Emil Ferris: The old saying goes something like, "there are no brave people, only people willing to carry their fear into battle." I think this is true also for suffering, mental illness, emotional scarring and profound catastrophes of the soul.

Paul Tumey: I am thinking of alchemy. Joseph Campbell said the true meaning of alchemy and the philosopher's stone was not to turn objects into gold to increase material wealth, but to turn suffering and pain into love and joy to increase spiritual wealth.

Emil Ferris: I like that. I like that a lot. And although I never said those exact words as I wrote the book I'd say you put your finger on what my mantra, if you will, was throughout the process. If you've ever refined gold, it's a rather brutal process. You heat the gold almost to the point you'll destroy it and then a gray tear of dross weeps out. Immediately the heat must be turned off. The dross is the impurity. Weeping and extreme pain are required to remove it.

Paul Tumey: I'm guessing you've refined gold, perhaps as part of your art training?

Emil Ferris: Yes. A ferris is an ironworker and I suspect that is what my family was way back when. I took to metalwork immediately.

Paul Tumey: That’s cool. “Ferris” probably comes from “ferrous,” which is a word used in connection with iron compounds. The gold refining process you describe leads to a thought I have that Art is the process of transmuting one thing into another. It’s kind of an arcane, secret knowledge of how that is actually done, the methods. Sometimes art contains within itself a record of various "monstrous” experiments that contains clues for others who might want to travel the same path. Such is the deep thinking your novel elicits!

Emil Ferris: I like that. I think it's true. I'm thinking about the question in regards to myself. Making art was such a given in the home in which I grew up that there was never any intentionality about it. So, for me to separate it out and consider how it works in the book, is to consider how it works for me, since Karen's mindset was very much mine as a child.

This interview is concluded in Part Two. Click here to continue reading.

Note: To raise funds needed to complete Book Two, Emil Ferris is running a crowdfunding campaign. Among the different levels of support, for $108 (the Chicago Cubs waited 108 years to win a World Series), Ferris will put a contributor into Book Two of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters. See YOU CAN BE IN MY GRAPHIC NOVEL.