On March 26, 1994, after four days of trial and a deliberation of forty, ninety, or 120 minutes, depending on what you read, a St. Petersburg, Florida, jury of three men and three women, each older than the defendant by at least a decade, declared Mike Diana to be the first American cartoonist officially guilty of obscenity.

The judge, an ex-naval officer, ex-prosecutor, and Rotarian, ordered Diana jailed. Diana’s girlfriend, Suzy Smith, wept.[1] Diana’s lawyer asked for his jewelry so it would not be stolen by his guards. Diana spent four days in maximum security while the judge pondered his sentence. The noise was unrelenting. The lights were on constantly. His cell had a metal bed with one blanket. Sleep was impossible. His company included murderers and rapists.

Because of pictures he had drawn.

When Diana returned before him, the judge asked what he had learned.

“I learned I don’t want to be in jail.”

“Is that all?”

"I learned what I did was wrong.” Diana didn’t believe that. But he sensed the judge wanted more than his previous answer.

The prosecutor demanded that Diana be imprisoned for three years, arguing, falsely, that he had made thousands from his art because the trial had made him famous.

The judge placed Diana on three years' probation. He fined him $3000, which he was to pay in $100 monthly installments, and ordered him to perform eight hours of public service for 156 consecutive weeks while working full-time. He was to be psychiatrically evaluated and have up to ten months' therapy at his own cost. He was to submit to urine, breath, or blood tests upon demand. (This requirement was stricken on appeal.) His residence could be searched at any time without a warrant. He was ordered to complete a course in journalistic ethics. He was forbidden contact with anyone under 18. He could not possess or create – even for his own pleasure – drawings that were “obscene.”[2]

Following his sentencing, Diana, his mother, and Smith went to a seafood restaurant. The tablecloths were sheets of white paper, and crayons were available for children to draw upon them. Diana drew fish defecating, then added breasts and penises to them. At his first meeting with his probation officer, he asked if he should give the police a key to his apartment or let them kick in his door? His P.O.’s attitude seemed, “Let’s just get through it as smoothly as possible.” Still, Diana kept his art in his car’s trunk and worked on it only at night.

I

Michael Christopher Diana had been born in New York City, June 9, 1969. At the time of his trial, he was five-foot-two and fit from running, calisthenics, and weightlifting. He had light brown, shoulder-length hair, which he had refused to cut despite his lawyer’s recommendation, because he felt it important to his identity as an artist.

His father taught junior high school science. He gave his son animal skulls and tapeworms preserved in formaldehyde and entertained him by attaching electrodes to a frog and making its legs jump. Diana’s mother kept house. He had a younger brother, now married with two children, and a younger sister, who, upon graduating high school, joined the Marines.

The children were raised Catholic, in Geneva, a city of 15,000 on Seneca Lake. (Scott LaFaro[3] was born there.) In nursery school and kindergarten, Diana wet himself during naps. He was tested and hospitalized and prescribed pills. Surgery on his urinary tract was considered.

Once, assigned to draw his family, Diana portrayed them nude, with genitals. Once, when his class collected material on the beach for art projects, he brought back a dead fish. By 2nd grade, his interest in art was so strong, his mother enrolled him in an after-school program.

When Diana was in fourth grade, his family moved to Largo, Florida, a city of 50,000. (D’Quell Jackson [4] was born there.) Diana hated the heat. He hated church. (He attended mass and Bible class until he was 15.) He hated the conformity and culture of a community, primarily elderly and retired, with lawn statues of flamingos.[5] He hated the schools, where teachers disciplined students with paddles. When he was 12, his parents divorced, and he stayed with his father.

Diana liked the Three Stooges. He liked Tales from the Crypt, “old, bloody, gory, religious art,” and the underground comics of S. Clay Wilson, Greg Irons, Rory Hayes. He had few friends. His only pet was a tarantula, to which he fed lizards and crickets. When it died, he cried for days. His father had taken over a fruit and vegetable store, which sold beer and cigarettes, cheap. Diana worked the register, drinking himself to better engage the customers.

He received A's in art and failed or barely passed everything else. Creating art, he felt, gave him the chance to be who he was meant to be. As part of this art, he made videos featuring himself as a slasher film-like killer. His mask was a money bag, which he had found in a dumpster and cut eye holes into. The “blood” he splattered came from corn syrup and food dye. Once he performed, masked, wearing all black, at a “night happening,” while a duo played electric guitar and bass. On his belt was an 18-inch dildo, which penetrated a baby doll, from which he had removed the stuffing, and whose head he had filled with heavy cream, which spurted from the eyes and mouth at each dildo thrust.

The crowd was “indifferent.” And his car was towed, costing him $300.

Diana created his first comic at 13. The cover depicted an eyeball dangling from a skull. On the second, a creature munched on a baby’s skull. In 1988, with a friend, he created his first zine, meaninglessly entitled HVUYIM. In 1989, he launched Angelfuck. Then came Boiled Angel.

It ran from 30 to 86 black-and-white pages, and was duplicated on the photocopying machine of the high school at which he was a janitor. He wanted Angel to be “as shocking as possible.” He wanted it to be “more extreme” than the UG cartoonists he admired. When #6 was found in the possession of a fellow busted for marijuana in San Francisco, the police sent it to law enforcement authorities in Florida, and Diana was asked to give a DNA sample to prove himself not the person who had killed five college coeds in Gainesville.

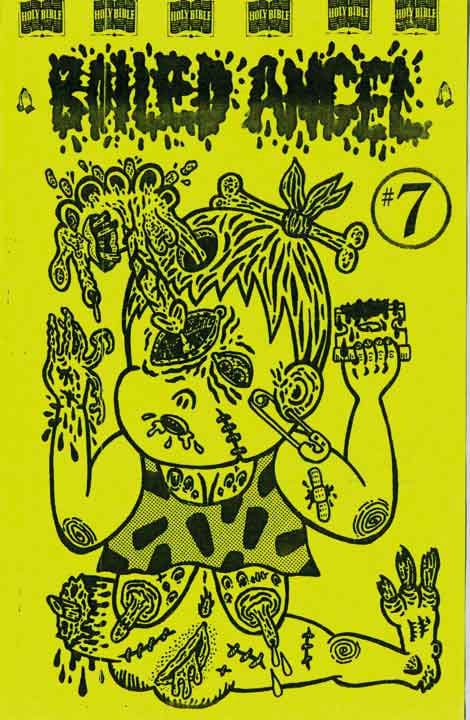

Angel’s circulation never exceeded 300. Its only sale inside Pinellas County, where St. Petersburg was located, was to an undercover police officer who wrote Diana claiming to be a fan. (“Far fucking out,” he called it. “Tasty.”) Diana sent him issues #7 and #8 (aka “Ate”).

The cover of #7 depicted a child with one leg amputated and one eye gouged out. Issue #8 displayed four naked women clutching a decapitated man. Inside, knives and dollar sign-decorated crosses penetrated people’s bodies. A penis entered a beheaded neck’s stump. A severed head fellated a cross-wearing monster. A huge penis entered a child so tiny that it exploded. A chalice cup is labeled “AIDS-infected Blood of Christ.”

Fourteen months after mailing #8 to the undercover officer, Diana was arrested.

Once courts decided that the First Amendment did not mean “no law” when it said “no law”and that some expressions were too sexually dangerous – or “obscene” – to be disseminated, issuers of these expressions became subject to criminal prosecution. Phrases defining limits were planted like stakes in the ground, and beyond them “speech” could not go. As time passed, courts moved these stakes and expanded this ground, and the public became able to read Ulysses and watch Carnal Knowledge. But markers remained.

In 1994, in Florida, a work was obscene if an average person, applying contemporary community standards, found it lacked serous artistic, literary, political, or scientific value, while appealing to prurient interests by depicting patently offensive sexual conduct. This definition said nothing about “disgusting” or “sick,” but it is difficult to believe that the jurors who convicted Diana did not feel these thumbs pressing heavily on justice’s scales.

On appeal, Diana’s attorneys argued lack of notice, entrapment, prosecutorial misconduct, that “community” should have been defined to encompass the entire state, and that a jury judging a work four years after its creation could not apply “contemporary” standards to it. I doubt any of these arguments gained traction with the appellate court. I think the guts of the case were “prurient interests,” “patently offensive,” and “serious.” And as with the jury, I suspect the calculated vileness of the work overwhelmed the court’s sensitivity to jurisprudence.[6]

On appeal, Diana’s attorneys argued lack of notice, entrapment, prosecutorial misconduct, that “community” should have been defined to encompass the entire state, and that a jury judging a work four years after its creation could not apply “contemporary” standards to it. I doubt any of these arguments gained traction with the appellate court. I think the guts of the case were “prurient interests,” “patently offensive,” and “serious.” And as with the jury, I suspect the calculated vileness of the work overwhelmed the court’s sensitivity to jurisprudence.[6]

Not that it would have had difficulty upholding the verdict.

Take “prurience.” Anyone who has seen the opening credits of Masters of Sex knows proving that is easy. Mushrooms and champagne bottles, railroad tunnels and crevices in geological formations can appear sexually suggestive.[7] While most people would seem more likely to snap Boiled Angel shut and abandon its vicinity than hunker down beside it with lubricant and tissue, once the state had Sidney Merin, PhD, a neuropsychologist known in local legal circles as “Sid the Squid” for his ability to cloud waters, testify that Angel’s depiction of “pain, mutilation and torture” would sexually arouse members of a “bizarrely unstable” deviant group, that hurdle was cleared.

And “patently offensive” was no barrier either. Remember the old joke? “Well, Mr. Jones,” the psychiatrist says, “the test results show you prone to bestiality.” “What’s ‘bestiality’?” says Jones. “Intercourse with sheep, cows, pigs, chickens...” “Chickens! UGH!” says Jones. If chickens can freak out Jones, what chance did exploding babies have with six average Floridians? No, once “obscene” words and pictures warrant time in the slammer, you can forget “prurience” and “offensive.” You better have “serious value” going for you.

Diana spent much of his five hours on the stand, trying to convey the worth of his work. He cited the influence on him of Salvador Dalí and Diane Arbus. He itemized the hours he put into each book. He explained that the nightly news’s reporting of serial killers and pedophiles, “each channel battling for the bloodiest stories,” had left him feeling people had become numb to murder and sexual abuse and wishing to shatter their indifference. (His approach, it strikes me, was similar to Pop Artists like Andy Warhol, whose soup cans and Elvises were said to document America’s consumer culture and celebrity worship. Only Diana was making it confront its lust for blood and perversion.)

But his testimony alone would not do.

In any case where attorneys fear how jurors’ pre-existing inclinations will define the phrases that are key to their verdict, they will provide “experts” to influence the jurors in the direction the attorneys desire. And since in a country as diverse as ours it is hard to find an issue about which experts will not disagree, jurors of almost any inclination will have an credentialed peg on which to hang it.[8]

During the second half of the 20th century, “obscenity” experts regularly trooped into court rooms to debate the existence of “value.” They included nationally known literary critics (Malcolm Cowley, Alfred Kazin), poets (John Hollander), novelists (Leon Uris), academics (Harry Levin, Mark Schorer), book review editors (Barbara Epstein, Eliot Fremont-Smith), newspaper columnists (Nat Hentoff, Dorothy Kilgallen), as well as eminent priests, ministers, rabbis, sociologists, and a co-author of the Kinsey Report.[9]

Diana’s prosecutor cleverly cut against this grain. Both his hardly-household-name experts came from the Presbyterian Church-affiliated Eckerd College, located in St. Pete.[10] One, James Crane (Art) testified that magazines “aren’t usually considered as art” since they were often thrown out.[11] (He also said that, he considered Diana’s work inferior to Prince Valiant and Peanuts.[12]) He conceded Angel might compare to “shock” art, like that of the Dadaists, but noted that once this had shock worn off, their work “didn’t last”; and work must endure in order to be art.[13]

Crane’s colleague, Victor Sterling Watson (Literature) testified that, for a creative work to have value, it must make “sense,”[14] must offer a creator’s “interpretation” of experience, not simply reflect it,[15] and must be “life-affirming... I mean, does it give certain values such as courage, fidelity, beauty, honor, love, friendship, community?” Boiled Angel, he felt, lacked “any context of interpretation.” Nor did it contain an “affirmation of anything that I would consider a positive value...”[16]

A basic rule of obscenity defense, as promulgated by Charles Rembar, who successfully represented Lady Chatterly's Lover, Fanny Hill, and Tropic of Cancer, is: The less defensible the work, the more “impressive” its defenders must be. (They might not register with jurors as much as a couple fellows from the local Presbyterian college, but they could disincline appellate judges from linking themselves with the Philistines in bound volumes on law library shelves for future generations to scoff at.) No disrespect intended, but Diana’s experts did not meet this standard.

One, Seth Friedman, published the San Francisco-based Factsheet Five, a magazine devoted to—and little-known outside of—the world of ‘zines. The other, Peter Kuper, a cartoonist from New York City, edited the leftist anthology World War 3 Illustrated, whose circulation never exceeded 3000. Moreover, neither emphasized Boiled Angel’s value as much as they argued that it wasn’t about sex but “victimization.” But it didn’t matter what Angel was about, so long as it prurient appealed to one of Dr. Merin’s deviants. That could only be offset by social contribution.

Friedman’s and Kuper’s lack of renown and misdirected focus were not their only problems. Their cities of origin allowed the prosecutor to inflame his closing argument by charging the jurors to protect Pinellas County from what might be “acceptable in the bath houses of San Francisco... (or) crack alleys in New York.” That was a cheap shot, but it made me wonder why the defense hadn’t had a Floridian, past or present, testify. Had they approached, for instance, Dave Barry, Judy Blume, Edna Buchanan, Michael Connelly, Harry Crews, Carl Hiassen, Duane Hansen, Peter Matthiessen, Tom McGuane, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Joy Williams? Had they all declined? Was their price too high?[17]

It also did not help that, at the time of Diana’s trial, the killer of those coeds, Danny (“The Gainesville Ripper”) Rolling was in the news, awaiting sentencing. This encouraged the prosecutor to call Boiled Angel “the sort of stuff that stirred up... somebody like Danny Rolling.... Step number one [is]... the drawings. [Then]... you’re into the pictures... [Then] you’re into the movies... [Then] you’re creating these scenes in reality.” In other words, he was arguing that drawing comix was the first step in a march to the turning the imagined scenes into actuality, so that Diana had to be stopped now before he began snuffing women, children, and babies.[18]

After three months, Diana’s lawyers had his probation stayed, pending the outcome of his appeal. In June 1996, without telling anyone but his parents, Diana moved to New York City. The day he arrived, his conviction was upheld.

New York refused to oversee Diana’s probation. So once a month he reported by phone to Florida. Once a month he mailed his $100. He completed a journalistic ethics course at NYU. He delivered food to HIV patients as his community service. And for the next two years and nine months of his probationary period, he remained forbidden to be in the presence of a 17-year-364-day-old or, I suppose, draw a murderously deployed penis.

New York refused to oversee Diana’s probation. So once a month he reported by phone to Florida. Once a month he mailed his $100. He completed a journalistic ethics course at NYU. He delivered food to HIV patients as his community service. And for the next two years and nine months of his probationary period, he remained forbidden to be in the presence of a 17-year-364-day-old or, I suppose, draw a murderously deployed penis.

III.

It will surprise no one who has read my views on transgressive art[19] that I found Diana’s prosecution to have been stupid, cruel, and a waste of taxpayer money. I am aware of no evidence that any kind of art causes people to act criminally, and even if there was, I do not believe the rest of us should be denied access to material simply because it might detonate our most marginal neighbor. And I think it beneficial for people to see what words-and/or-pictures disturb them, so they can search themselves to see why that is

To me, Diana’s prosecution seems more like bullying than justice. He was a single guy, without corporate backing, publishing a barely read comic. His drawings were crude and off-putting, not seducing or rousing one to action. His stories were hardly commanding enough to seize control of one’s unconscious. He did not, in detailed prose, describe the nailing to the floor and dismemberment of a woman, like Bret Easton Ellis in American Psycho. He did not salaciously link sexuality and automobile accidents – “the erotic delirium,” the semen spilled, and pubes lacerated – like J.G. Ballard in Crash.[20] Diana’s aesthetic seems like The Three Stooges Meet Freddy, or Rory Hayes guest-artists Little Orphan Annie, the oddity of the juxtaposition making one chuckle, if ruefully, at the carnage, the continually building how-can-he-top-this bank of outrages fascinating like a playing card tower. It does not, I say without hesitation, make one think, “Gee, that sounds good. Where’s my chainsaw?” and head for the local preschool. Diana was a lone weirdo (in the best sense), a zine-making guy seeking footing in the world, not an author of lit-ra-choor, anchored to important friends in important places. He was an easy target to beat on.

If the State of Florida was engaged in something beyond a sadistic exercise in PR, a good faith effort, say, in deterrence or rehabilitation, I have some seat-of-my-pants-researched news for it. In 2012, to accompany a European tour of Diana’s art, Divus published a two-volume slipcased compilation of his work, America. One volume, Live (400 pp.), was entirely black and white and the other, Die, (128 pp.) mostly color. By my calculation, Diana would have been on probation from approximately March 28 through June 28, 1994, and from June 8, 1997, through March 8, 2000. These compilations only give the year of completion of each work, so I have confined my study to 1998 and 1999.

If the State of Florida was engaged in something beyond a sadistic exercise in PR, a good faith effort, say, in deterrence or rehabilitation, I have some seat-of-my-pants-researched news for it. In 2012, to accompany a European tour of Diana’s art, Divus published a two-volume slipcased compilation of his work, America. One volume, Live (400 pp.), was entirely black and white and the other, Die, (128 pp.) mostly color. By my calculation, Diana would have been on probation from approximately March 28 through June 28, 1994, and from June 8, 1997, through March 8, 2000. These compilations only give the year of completion of each work, so I have confined my study to 1998 and 1999.

Live has nine works from this period. In them, a child stabs to death his parents and three siblings, machine guns hundreds of school children, and kills himself. A teenager blows up a school with 3427 students and teenagers inside and urinates on their graves. Aliens invade Florida and behead and eviscerate naked citizens. A naked woodsman ejaculates while felling a phallus-resembling tree. A fellow fearing he has been invaded by insects slices off his own nipple. A skull drips semen after sex with a giant cock.

When Diana’s probation officer would remind him that he could violate his probation by drawing, he would reassure her, “Of course, I’m not drawing.”

But of course he was.

IV

Becoming America’s most shocking cartoonist is a bit like becoming its fastest runner, except that instead of pushing one’s body, one pushes one’s mind. Both feats test courage and commitment. To both, upbringing and obsession contribute.

Diana had to identify where our society’s nerves were rawest and squeeze that spot until his knuckles whitened, despite its shouts and screams. This act set him apart at the same time it elevated him. While his prosecution gave him name-above-the-title power in some circles, it also cost him. People feared that if they asked for his art, it would make their doors a target for the jackboots. So while the tag “Only Cartoonist Ever Convicted...” may ring Diana’s neck like Olympic gold, a Wheaties box was never in his future.

At present Diana shares a three-room apartment with two other artists in what had been a party house for Argentine skateboarders in the Fort Washington section of Manhattan. He scrapes by, supporting himself primarily through his art. His website sells his drawings, paintings, comix, t-shirts, patches. He contributes work to others’ comix and zines. He designs the occasional album cover. He has graphic novels in progress. Manhattan’s galleries elude him, but he has exhibited at them in London, Prague, and Berlin – and at squats in abandoned factories in France. He will have a joint show in Paris with Stu Mead, an American ex-pat painter of sexually explicit works, often involving juveniles. A documentary about Diana’s trial, to which he is contributing animated clips, is being made by Frank (“The Godfather of Gore”) Henenlotter and Mike Hunchback, the punk guitarist/song-writer.

While writing this article, I had one phone interview with Mike Diana and several email exchanges with him. At the end, I asked him, “Was it worth it? If you had it to do over again, would you?”

“Since I was little,” he said, “I wanted to draw things I liked... I wanted to share my drawings with others. When I was in Florida, in my teenage years, I wanted to make shocking art. The oppression is so heavy there, it makes you want to rebel. The religious folks there cause this to happen. I wanted to offend those that needed to be offended, and Largo, where I was living, is overrun with those kinds of people. I never had a feeling that I did anything wrong, I was just using my freedom of speech. It’s not my fault nobody else in that part of the United States wanted to exercise this freedom. Yes, I would do it again and again.”

“Since I was little,” he said, “I wanted to draw things I liked... I wanted to share my drawings with others. When I was in Florida, in my teenage years, I wanted to make shocking art. The oppression is so heavy there, it makes you want to rebel. The religious folks there cause this to happen. I wanted to offend those that needed to be offended, and Largo, where I was living, is overrun with those kinds of people. I never had a feeling that I did anything wrong, I was just using my freedom of speech. It’s not my fault nobody else in that part of the United States wanted to exercise this freedom. Yes, I would do it again and again.”

I mentioned that, at artwhore.com, he had advised others to “Draw as sick as you can.” Why, I put to him. Who or what was being served?

"I was trying to say, if you want to make art that is risqué or that most [people] don’t like or feel is unsavory, just do it, Draw what you want. Don’t let the bastards that are always grumpy get you down, discouraging you from what you create. It is important to the artist and this free society we live in.”

I thought about that.

It was, of course, by no means certain that permitting Mike Diana to keep drawing children being fucked to death would have led him to personal growth, or to work that museums would hang, or which would lift civilization further from the mud. It did seem, though, that his continued application of ink to paper had not resulted in any of the state-warned-against conduct on his part or, as far as I knew, triggered anyone else’s felonies.

Beyond that, I only found myself thinking thoughts I had already thought and writing words I had previously written. (It was so wearyingly discouraging to think that in the late 20th century we had not progressed beyond the nonsense of State v. Diana. Of course, we are now well into the 21st and look at the megalomaniacal, malicious death cap we have elected president.)

So, seeking freshness, I asked a few people whose work and opinions I respect what they thought about Diana. Here are their responses.

One thing I hated about the way Mike Diana gets processed by most people is that his comics are awful, that they are beyond-the-pale offensive, and that we defend him anyway because of principle.

I think all this is wrong.

I think Mike’s comics are funny. I think they’re pretty clearly “white trash shenanigans” stuff more than comics exploring the real terrors of the soul, like Simmons or Columbia do, and I think a lot of his comics art is attractive. -Tom Spurgeon. Editor of The Comics Reporter

I was inspired (by) his surrealist visuals... (and) unfurled psychedelic id. Simpler minds may only want to feel appalled by the vileness of his subjects but there is great, eye-popping beauty to his images... He has an innate sense of layout and optical play. His imagination and attention to absurdity are more commanding of my attention than any institutional artist. -Jon F. Allen. Writer, cartoonist and co-editor of Pop Wasteland.

I see interesting parallels in Mike Diana’s case with the start of the first Gulf War. Police action against him started the same time [as] the cycle of war and violence conducted by [the] American elite. And you take draconian measures against the guy who never did any actual harm to anyone and who was only drawing comics and you don’t have any call for legal responsibility for people who were involved in premature deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent people at the same time. And you have official psychiatric evaluation of “criminal” Mike Diana who was only in charge of his own comics zine but you don’t have any psychiatric evaluation of Madeleine Albright for an example who was in charge of heavily armed superpower... Mike Diana was the victim of the same school of thinking which finds suspect and guilt everywhere but never in themselves.[21] - Wostock. Filmmaker and cartoonist

One of these people, J.T. Dockery, author/artist of Despair, responded at such length and in such depth that I felt he deserved stand-alone recognition. So here’s...

Satan, Mike Diana, At Least One or Two Other Things & Me:

An Appendix by J.T. Dockery

With Mike Diana's work, I can feel the imagery moving along ley lines of artists before him who charted geography in lands that made the squares twitch and recoil but also sparked an audience--however limited-- alternately hungry for subversion and wills to be weird such as: Rory Hayes, S. Clay Wilson, Joe Coleman, along with a soundtrack of lyrics by The Misfits and artist Raymond Pettibon's Black Flag album covers, I can observe Diana surfing the waves of punk and heavy metal, its subcultural imagery.

It's not for nothing that the same Florida that begat Diana's comics also begat the death-metal genre of bands like Obituary, Deicide, and Morbid Angel--with their reveling in blasphemy, Satanism, and at least one or two other things--concurrent with the late '80s/early '90s/Diana's pressure cooker of Boiled Angel that got him in such community-standard-hot-water in the "Sunshine State." I'm aware that the court would not allow any evidence of context or tradition, so no entering into evidence any previous underground comix, etc. to establish a heritage for the kind of "folk art" that cuts the guts right out of the American apple pie. I would argue that tradition--and Diana's place in it--is one of the nobler emanations of American arts and letters/(sub)culture.

I also can't imagine his work being made and distributed outside the context of the '80s/'90s zine scene, with Factsheet Five serving as central hub for distribution of weirdo print matter traveling across state lines before the rise of the internet, giving Diana an underground/alternative audience outside of his immediate community. And I can't imagine his prosecutors having any sense of the zine scene, punk rock, heavy metal, or underground comix (even in their own backyards), actively dismissing any context as nothing but degeneracy. (What did one of the Florida prosecutors say about New York crack alleys and San Francisco bathhouses again?)

I would say Diana’s work is evidence that he's processing the hypocrisy of avowed American normalcy and, furthermore, if he was capable of doing any "actions" delineated in his work, he WOULD NOT be MAKING that work. It's the repressed and those who fear the shadows full of their own darkness who are the real scary beasts, crouching low and breathing heavy, preying on society/individuals; the old fallacy of failed thinking that if someone makes transgressive art, he or she is, it follows, either capable of performing transgressive acts and/or inspiring the transgressive acts depicted. (Not to mention the reactionary fear that comes from observing an artist drawing the spears that poke the sacred cows of the status quo/decency/the current community standards of any given neighborhood conservative Christian church). It reminds me of the scenario of the elected conservative politician who endorses the most foul homophobic legislation, harping on enforcing his morality crusade, who often seems to be the most likely to end up caught with his pants down engaged in illicit acts with other men. I find myself thinking also of serial killer John Gacy. (Did he ever paint BEFORE he was in prison?) Certainly one can almost regard his strange paintings as the result of an incarcerated killer who is restrained from the option of further murder, with killer coming first, artist second by a wide margin. If Gacy had it within himself to put his murderous impulses into paint, he wouldn't be a killer. Speaking of Joe Coleman, he's often said that if not for discovering the outlet/s of art, he thinks he would have become a killer and/or some kind of criminal.

But maybe talking to/about Mike Diana right now is perfect timing, when, somehow, a "reality television" celebrity/smoke-and-mirror-millionaire has been elected (is that vomit I taste in my mouth?) to the highest office of the land. Whether he's getting caught on a hot mic endorsing sexual assault or generally spouting fragmented ill-formed hate speech, Donald Trump seems like a Diana character to me. Which is to say, a vile/violent walking, talking caricature of himself (either not self-aware, or so deeply cynical that he IS aware, that he's playing a character for an intended audience). And yet he was recently tossing around, on the bathroom stall of Twitter, that threadbare notion (what year is this again?) of prosecuting citizens for burning the American flag. Which reveals, at best an ignorance and at worst a denial, of what the law of the land protects as freedom of speech.

I think of William S. Burroughs's "Roosevelt After the Inauguration". Burroughs had the experience of being prosecuted on charges of obscenity--and it seems to me that casting Trump in the Roosevelt role and adapting/updating Burroughs into a comic, as delineated by Mike Diana, would be--as I imagine the result in my mind's eye--a perfect summation of the current situation. (I'm not exactly sure why Donald Dump can't be deemed legally obscene, ha/ugh.)

Of course, invoking Burroughs as positive to the negative example of Gacy, one could argue, subverts my analogy – being that, indeed, Burroughs did accidentally – as the official story goes – shoot and kill his wife. Unlike Gacy though, Burroughs was not a serial killer, and himself viewed the act, however unintentional, to be the central motivating fact of his career as a scribe, and the corpus of his work as something of an atonement, or rectifying/attempt at redemption for having been an instrument in the bodily death of Joan Vollmer. No matter where one lands on the Burroughs question, I'd venture to say there is no meaning/understanding/criticism of art without including context (and then there's the issue of not separating the artist from the art, which is to say: seeing value in failed/flawed human beings capable of producing interesting work despite their inherent flaws, as transcendence of flaws and failures, not because of the same).

What's interesting to me is that 1. Diana was legally prohibited from making art, period (not merely a judgement of specific works in print, but a judgement/censure of any future works) and 2. what that fact means to an artist, how it changes him. On the back end of that, I'm aware that the actions of the prosecuting authorities in Florida ultimately negated their own goals, meaning that as the events were happening other artists and writers and institutions stepped forward to make statements in his defense – (it's difficult to imagine Neil Gaiman discussing Mike Diana's work if not for the situation of his prosecution) – and generally making an obscure artist more well-known by the very processes of censuring/censoring him.)

Like anything else, if one can't take one's faith being satirized, or one's country/its leaders being satirized, then what occurs to me is that it is more pudding-proof that one's religion/government – and humorless faith in such institutions/individuals within those institutions – can't, in actuality, BE all that powerful. Not if any reaction to any skewing of the supposed power of faith/government in the form/s of art/the arts is perceived as an attack, a threat, which must be eliminated. As I would say of a government so afraid of its own citizens that it spies on them, that's playing from a weak position.

There seems to be a moral/lesson in this story for those in power willing to pursue censorship, for the short term silencing/derailing of careers of artists. History reveals that censoring artists/their works seems to never accomplish much more than making the artist/their works censored/censured more famous and studied than if the authorities had just let them work/satirize/poke the sacred cows in the warm amniotic fluid/peace of freedom of expression.

I think of William Tyndale, put to death in England for illegally translating biblical scripture into the English language, and yet, within a generation, his work was put into the language of the King James translation, the official version, sanctioned by the throne which killed him, ultimately making him as important an architect of the language as William Shakespeare. The Tyndale name is not well known outside of the circles of biblical scholars, yet every time we say a word such as "atonement" or utter a phrase such as "eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth," that's all Tyndale/14th century words and phrases from his translation. And they strangled/burned him for his efforts.

That's a major-league digression. But, hell, Diana is more like Tyndale than his church-going, painfully middlebrow, corn-pone persecutors. At least we don't torture or kill our artists, writers, philosophers, scientists, etc. simply for doing what they do, and exploring ideas/expressions that run contrary to the status quo and legally protect their freedom of speech. I mean, at least...for now.

Endnotes:

[1].Smith (aka “Suzy Morbid”) had been drawn to support Diana because she had been fired from her job as the hostess of a public access cable TV show after showing a tape of the singer GG Allen urinating and defecating on stage. She found Diana “nice,” “shy,” “lonely,” and “depressed.” “He needed somebody,” she concluded.

[2].Since, arguably, nothing is “obscene” until a judge or jury rules it so, and since the jury had not identified what part of Diana’s work it found criminal, this placed a burden on Diana’s judgment. It would have also seemed counter-productive to those who believe that if one is possessed by inner demons, which some in the courtroom seemingly believed Diana to be, it lessens the chance of their acting anti-socially if they can release through art the pressure these demons generate.

[3]. Look him up.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. . Largo recently made national news when its City Commission voted 5-2 to remove its City Manager because she was transitioning from male-to-female.

[6].The only part of the court record I was able to review was Diana’s opening appeal brief, so my understanding of the case may be incomplete. But since this brief is likely to have recited the facts in the light most favorable to Diana, and since my analysis will focus on his defense’s shortcomings, what I have to say may not be terribly undercut.

[7]. If Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree is to be believed, some men may even find watermelons sexually irresistible. And at least one serial rapist/murderer is said to have been inspired by Cecil B. DeMille’s Ten Commandments. See: Murphy. “The Value of Pornography.” 10 Wayne L.Rev. 668 (1966).

[8]. Speaking of “experts,” journalists ring them in too when purposes require, and, coincidentally, I have just heard from the always-fascinating Ruth Delhi, PhD, who has been on a lengthy, silent meditation in the mountains of Peru, but read the first part of this article and passed along a hand-written note, via a touring charango player. “What an unusual child!” she said of Diana. “And his parents were amazing. They recognized his interests and encouraged them. They didn’t confuse their son’s playfulness and imagination with pathology, even though his behavior was extreme, but accepted it, removing its negativity, and helped him function.”

[9]. Even cartoonists were not unworthy of such defenders. When the owner of an Oakland gallery was prosecuted in 1970 for displaying the art of UG comix Snatch and Cunt, the Founding Director of the UC Berkeley Art Museum testified on his behalf.

[10].U.S. News & World Report currently ranks it 127th out of 180 liberal arts college in the country.

[11]. So much for newspaper comic strips, comic books, political broadsheets and pamphlets, rock show posters.

[12]. S. Clay Wilson was not discussed.

[13].This assessment would startle Yale University, which recently celebrated Dada’s centennial with a five-month long exhibition.

[14]. One might cite Pablo Picasso to the contrary: “The world doesn’t make sense. So why should I paint pictures that do.”

[15]. Or one might cite Andy Warhol’s films, William Burroughs’s tapes, or Marcel Duchamp’s urinal to the contrary.

[16]. Watson was not asked about the “courage, fidelity, beauty, etc.” within, say, Louis Ferdinand Celine or Nathanael West, Otto Dix or George Grosz.

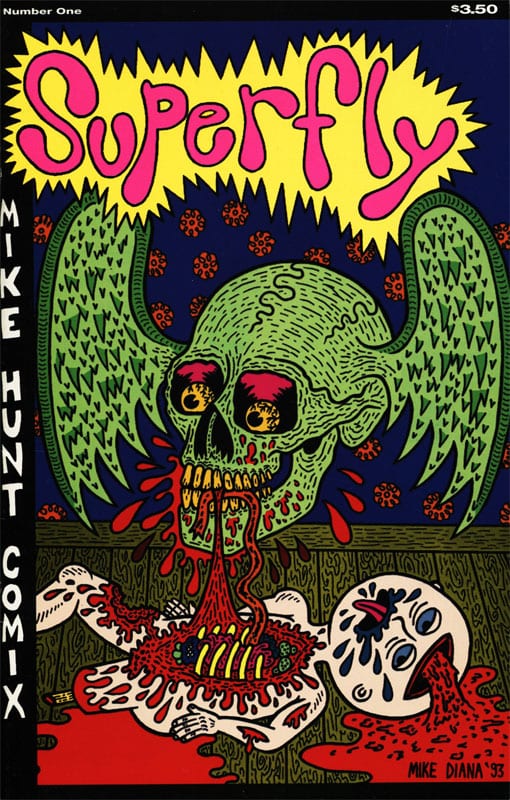

[17]. Diana’s attorneys had intended to call a third expert, Shane Bugbee. After Diana had been charged, Bugbeen had reprinted Boiled Angel #7-8, published a new comic by him, Superfly (a bat-winged skull devours a corpse on the cover), and arranged a gallery show of his work in Chicago. But Bugbee’s nom de publication was “Mike Hunt” (get it?), and since this was how he was identified on the defense’s witness list, his testimony was excluded due to his identity not having been properly disclosed.

Not that he would have solved the impressiveness problem, I daresay.

[18]. According to Diana, the alternate (non-voting) juror told him he had been done in by “the serial killer slant.”

[19]. If you haven’t, I refer you to my essay collection, Outlaws, Rebels, Pirates, Free-Thinkers, & Pornographers, Fantagraphics. 2005.

[20]. I did not watch “slasher” films, so I can’t pull comparisons from them. I’m sure there are many.

[21]. Wostock’s dating of the war and identity of the Secretary of State responsible are off, but his point is well-taken.