Jerry Dumas was a cartoonist’s cartoonist. Specifically, he was a life-long associate of Mort Walker’s, a member since 1956 of “King Features East,” as the Walker “studio” was sometimes called when Walker and his partners produced several comic strips simultaneously. Dumas was a part of the team that met weekly to propound jokes for both Beetle Bailey and Hi and Lois—and other strips as Walker came up with them—and he also drew some of the product from time to time. Dumas died November 12 at his home in Greenwich, Connecticut, from neuroendocrine cancer. He was 86.

Since April 18, 1977, Dumas had been producing a comic strip of his own, Sam and Silo, a reincarnation of one of the medium’s most eccentric creations, Sam’s Strip, in which the title character was the proprietor of his own comic strip that he ran like a business. Sam frequently encountered characters from other strips, tried to hire some of them, stored unemployed speech balloons in a closet against the day they might come in handy, palled around with John Tenniel characters from Alice in Wonderland, kept arrow-pierced hearts and shining light bulbs in a handy prop room with a supply of labels (“desk,” “table,” “phone”), and watched out constantly for disappearing border lines and characters with erasers.

Dumas’ handiwork extended far beyond the funny pages: he was a gifted writer, an insightful poet, raconteur, painter, athlete and essayist. He was a storyteller with words alone as well as with words and pictures combined. In quiet unassuming prose, he recorded his apt observations of the follies and frailties of human nature in articles for The Atlantic Monthly, The Smithsonian and the Washington Post. He wrote a weekly column for Greenwich Times, the last of which appeared a few days before he died, titled “Ageless Tips That You’ve Reached a Certain Age.”

“Cartooning is a great American art form and Jerry was one of the people who shaped it,” said Greenwich Times Managing Editor Thomas Mellana, “But people didn’t love and respect Jerry because of his accomplishments. They loved and admired him because he was such a good man, and such a great guy. He was someone who took genuine interest in others. A phone call to the newsroom from Jerry was never just about the business at hand. It was a conversation. And your day was made better by it. Every single time. We at Greenwich Times were extremely fortunate to be able to call him one of our own. We will miss him greatly.”

“Many people claimed to be, or are honored as, ‘Renaissance Men,’ but Jerry simply was,” said comics historian Rick Marschall, quoted by Robert Marchant in his Greenwich Times obit. “And the artwork he did on certain of his own strips— especially his Sam and Silo Sundays— were masterpieces, utter masterpieces, of detail, ‘feathering,’ visual substance and plain inky love.”

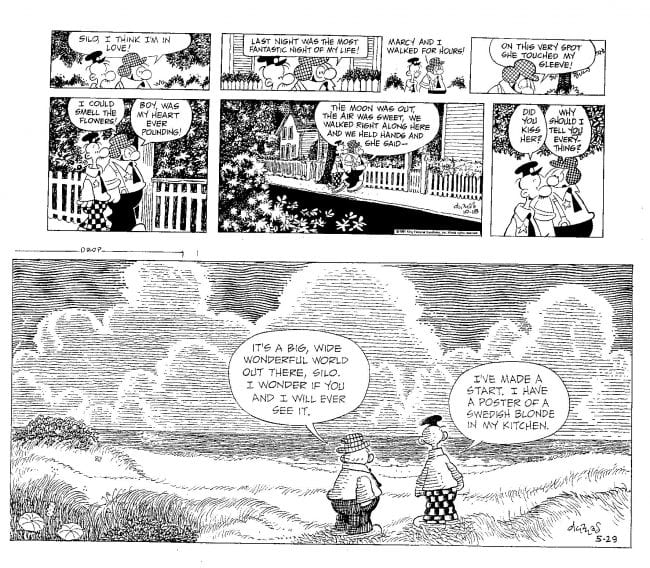

Here are samples of Dumas’ Sam and Silo Sundays. I’ve admired Dumas’ work on his strip for a long time: sometimes he produces visual symphonies of texture and shading just for the sheer fun of it—that is, neither the gag nor the pictures conveying it require the embellishment he so happily lavishes, sometimes, on the strip. He was drawing for the sheer sake of making a drawing.

Marchant quotes Bill Janocha, a Walker assistant who worked with Dumas on Beetle Bailey since 1987. Said Janocha: “Jerry was a great story and joke teller, with a seemingly unflagging memory for details and color in his tales.... He spared nothing in his descriptions of past interactions, personalities and commentary on the beauty he saw in his surroundings and the quirks in humanity.”

Gerald John Dumas was born on June 6, 1930, in Detroit to Frieda Holm, a nurse, and Floyd Dumas, a firefighter and aspiring boxer. Jerry started drawing cartoons when he was only nine years old and continued through high school, when he started selling them.

“I used to get on the bus and go into downtown Detroit and sell cartoons to Teen magazine for $2,” he said during an interview in the National Cartoonist Society newsletter. “I really thought I had it made. I was aiming for The New Yorker and the Saturday Evening Post.”

He finally realized his dream, but not until he was twenty-six when he was published in the Post; getting into The New Yorker took a little longer—until he was twenty-nine.

Dumas served in the U.S. Air Force and later enrolled at Arizona State University; he graduated with a degree in English in 1955. Wrote Marchant: “A painting teacher, recognizing his ability, suggested he move to New York City and study with the Abstract Expressionist school then in its ascendancy. But Dumas, who had a childhood fascination with comics and had already drawn a paycheck for his early cartoon work in Phoenix, chose the path of an ink-stained gag writer over the fine arts.”

He moved to Greenwich, Connecticut in 1956. On June 21, 1958, he married the former Gail Gaskin. She survives and lives in Greenwich.

“It was in June of 1956,” said Marchant, “that Dumas rolled down the Greenwich driveway of Mort Walker’s studio with an introduction from a friend.” Walker liked what he saw in Dumas’ portfolio. “How soon can you start?” asked Walker, to which Dumas replied, “Right now,” according to an account provided to Marchant by Dumas’ son, Timothy Dumas. “Dumas and Walker embarked on a fruitful collaboration on the funny pages.” “We had a lot of fun together,” Walker recalled, “He was very good at nostalgia, the good old days. So pleasant to be with. I’m really going to miss him.”

Dumas was “the creative force behind Sam’s Strip,” said Marchant. “An early post-modern take on popular culture, the strip’s central character, Sam, runs his strip like a television show and brings on guest cartoon characters from other strips— Krazy Kat, Dagwood, and Charlie Brown. Dumas meticulously drew every character in their original style without assistance.”

Self-referential and high-concept, “the comic about comics,” as it came to be known, was a big hit among cartoonists and cartooning afficionados like me, who could appreciate the insider-comedy that laced it through and through. Starting October 16, 1961, it proved too far ahead of its time and ended June 1, 1963 after only 20 months. But it was an unadulterated joy while it lasted.

The work was later collected and republished by Fantagraphics. Here are a few samples of this famously in-joke epic.

In the book collection, Dumas wrote about how the strip came about:

“All through the late 1950s, Mort and I worked together three or four days a week, however long it took, doing the artwork for the daily and Sunday Beetle Bailey strips. At that time and on into the 1960s, we were the only writers for both strips. ...

“We both had a fairly thorough knowledge of comic strip history, so just for fun, just for each other, we began doing gags about comic strip characters. ... The idea soon came up: what about having a guy who ran his own comic strip as a business? ... But what should this character look like?

"One day Mort was doodling around and I was looking over his shoulder. He drew a face that looked roughly like the short character, Mac, in Tillie the Toiler. I said that he didn’t look different enough, didn’t look unique. We both stared at the paper for a minute or two. I said, ‘Draw a line across the middle of his face. Let’s see what that looks like.’

“Mort penciled a line from Sam’s ear to his nose, cutting off the whole lower half of his face [which was suddenly hidden behind Sam’s shirt collar]. Now he looked different and that’s the way, for better or worse, he stayed. ...

“Mort and I split the gag writing, and I did all the drawing, except for the lettering, which Mort did. ...

“When Sam’s Strip started, there were no copy machines, or no good ones anyway. All the Sam’s Strips were drawn from scratch, laboriously penciled and inked, and research took a great deal of time. I took pride in copying an artist’s work exactly—even Tenniel’s Alice in Wonderland drawings.”

“The intriguing concept,” said Marchant, “ — and precise execution — was typical of Dumas’ work. Dumas collaborated on other enterprises, too—with Mort Drucker on Benchley and with Mel Crawford on Rabbits Rafferty and McCall of the Wild.

“Wonderfully gifted, he could make a line that was beautiful and crisp. And he was a master craftsman and a good ‘ghost,’ someone who is capable of taking on a number of different styles, and do it with aplomb. And among his peers, he was intensely respected,” said Brendan Burford, general manager of syndication for Hearst’s King Features Syndicate, quoted by Marchant.

“In person, he was quick witted and funny and incredibly well-read—he seemed to know everything. An amazing athlete, too. He was one of those men you ask— how did he even fit this much into his life? Really versatile as a human being,” Burford finished.

“In the end, humorists write about humanity, as they see it,” Dumas wrote in an essay published in the Washington Post in 1993. “If a cartoonist is to write about human nature, he must people his comic strip with every facet of human nature he can think of: the sensitive and the insensitive, the lazy and the energetic, the smart and the stupid, those in authority and those who have none.”

“A serious athlete, Dumas earned a New England and Connecticut handball championship in the doubles category,” Marchant said. “He also cultivated four vegetable gardens he maintained at his backcountry residence, one for four different kinds of onions, another for garlic and carrots, a third for spinach and arugula and a fourth for a wide variety of tomatoes. He gave away much of the produce to friends.

“Beside toiling in the earth,” Marchant concluded, “— Dumas was often pondering the larger questions in life, and the pleasures it offered — even a small laugh at a well-executed gag.” And he quotes Dumas quoting Nabokov: “Nabokov said, ‘Our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.’ That’s the big picture. But the small picture is the one we gaze at most, and it is a picture of lovely and infinite variety.”

I met Jerry several years ago when I was visiting Mort Walker to interview him for The Comics Journal. Walker took me to lunch with his sons and a couple friends, including Jerry. A week or so after our lunch conversation, Dumas wrote me (in italics, forthwith):

Even Mort and I can’t believe how long we’ve been together. Just think, I’ve been writing Beetle gags for all but the first five-and-a-half years of its existence. We started working and playing ping pong together when he was 33, and now he’s 85. We had ferocious games in the basement after lunch each day—he was good—and I would spray sweat all over my side of the table and some of his, and I would go through several shirts and t-shirts. Mort would joke that I was the only cartoonist he knew who went to work each day carrying several changes of clothing.

This was true, but one of his inaccurate memories is when he claims that I never took up golf because the first time I played, in a big cartoonist gathering, I got the booby prize for the worst round of the day, and I was so angry I swore never to play again. The real reason, of course, was because I was already a champion four-wall handball player and would soon be Connecticut state champ (twice) and New England champ (once), and it was the game I loved, and there wasn’t time to do everything. A handball match takes about two hours, and I would lose up to six pounds, while golf took six hours and you gained two pounds.

Did Mort tell you this one? Early on, I wasn’t making that much money, but I had managed to invest, all by myself, astutely in the stock market, and had built it up to where my holdings were worth a considerable sum. All blue chip stocks. Then a so-called stockbroker friend convinced me to put the whole thing into one stock that was going to go through the roof. It turned out that the chairman and president [of that company] were crooks, and the stock fell through the basement. One day I complained to Mort that I didn’t know how it could have been fraudulent because, after all, the company’s accountants were considered the best in the country—Ernst & Ernst. Without looking up from his drawing, Mort said, “Well, Ernst is okay, but Ernst is a crook.”

The humor in that line has to do with the exact wording. I’ve heard other people try to tell the story by saying, “... but the other Ernst is a crook.” And that, of course, screws it up.

The column I write is published every Thursday in our daily paper, Greenwich Times. Nobody in town talks to me anymore about Beetle or Sam and Silo, but they talk all time about the column, strangely. I can write about anything I want, and it can be humorous, poignant, topical, historical—anything. A few times I’ve been able to make readers laugh and cry during the same 500-700 words, which is satisfying. I just hope they weren’t crying at the funny bits and laugh at the tearful parts.

If I had to choose, I’d pick writing over drawing. I’ve been happiest seeing my stuff published in The Atlantic, The New Yorker and especially Smithsonian (they bought a great many pieces). I had appeared in Smithsonian’s pages for several years before I realized their circulation (then over 2,000,000) was a great deal more than the other two esteemed publications.

I do all my reading in bed between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m., for some unknown reason. It doesn’t bother my wife: if I’m quietly turning pages, it means I’m not loudly snoring.

One of Dumas's pieces for for The Atlantic Monthly (June 1997) was entitled “Visitations: The Graveyards of a Lifetime.” To quote it (as I’m about to do) in an obituary about the writer seems a little grotesque perhaps—the coincidence of the occasion and the topic doesn’t quite justify its inclusion—but Jerry loved cemeteries, so he’d allow it. Besides, it’s another example of Dumas’ dexterity with words and gentle humor, so here it is (in italics)—:

I am drawn to cemeteries. I’ve enjoyed them since childhood. I have no wish to be placed in one anytime soon, of course, but I am lured by their green serenity, riveted by all those shimmering echoes. ... I like the look of the cemetery, with its calm, endless rolling hills, all the gravestones, the weeping willows, and the ponds, so different from the scraggly, screeching, monotonous streets that encircle it. ...

With his wife while on their honeymoon, traveling from Phoenix, where they married, to Dumas’ apartment in Connecticut, he stopped en route to visit the grave of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), and Jerry noticed the adjacent grave of Clemens’ daughter, Susy.

I bent down a little [he wrote] and read aloud the inscription beneath her name—:

Warm summer sun shine kindly here,

Warm Southern wind blow gently here,

Green sod above lie light, lie light—

Good night, dear heart, good night, good night.

Tears came to my eyes; I turned away so my wife couldn’t see, and found myself face-to-face with two elderly women. One of them said to me, with some anxiety, “Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “I’m on my honeymoon.”

On another occasion, he went to the funeral of the highly regarded and widely loved pastor of a local church, Nate Adams. Dumas saw the man in his coffin, and then he decided to go to the interment. Dumas arrived late—

Most people were just leaving [he wrote]. I parked and went over to the grave site and started talking to a man in a blue serge suit. We looked down at the green fake-grass fabric that covered the grave. Others drifted over to listen to us. We spoke about what a good, kind person [the deceased] was, and how he would be missed.

Finally, I said: “What’s that bulge there under the covering?”

My companion said, “Why, that’s the urn with the ashes.”

I said, “I just saw Nate Adams. He wasn’t cremated.”

The blue serge suit said, “Nate who? This is Bill Gilman, from Westport.”

I got in my car and drove away. They all watched me go.

That keeps happening, but it’s all right. Someday it’ll stop.

Dumas wrote a column one time about jokes that didn’t go over; here’s one—:

I told this one to my wife:

A man asks a passerby, “Do you speak Yiddish?”

The man shakes his head.

He asks a second man but gets no answer. He stops a third man and says, “Do you speak Yiddish?”

The man says, “Yes, I do.”

“Good. Could you please tell me the time?”

My wife said: “Have you reset the upstairs clock since the last time the electricity was off?”

(She would never quite understand Jerry’s fascination with cemeteries either.)

Dumas had a keen sense of cartoon comedy. And every once in a while, he’d write me about something he’d particularly enjoyed. (I don’t mean to suggest that we were constant correspondents; we weren’t. Jerry might write once a year—at Christmas or soon thereafter, to thank me for sending him a Christmas card.) Here’s a sample (in italics)—:

One of the smartest and best-drawn cartoons I ever saw: a small, pompous king has emerged from a grand doorway and is strutting down a walkway to his royal carriage (or limo). Right in front of him, two little guys are unrolling a red carpet (if the drawing was black and white, I must be imagining the red), and behind the king, two other little guys are rolling the carpet right back up. No words. The idea says a lot about the condition of man.

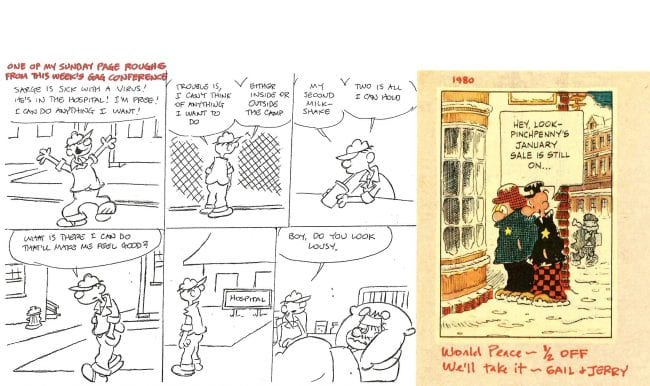

Once Jerry sent me a copy of one of his rough gag idea for a Beetle Bailey Sunday; I’m posting it near here—with another scan of a Dumas Christmas card, featuring Sam and Silo from 1980. The members of Walker’s gag-writing team meet once a week, and they all brought in their gags sketched out like this one.

Dumas was a cartoonist, although he might prefer “humorist.” He was also a thinker and a ponderer of all things. And he wrote a book-length free verse poem derived from his youth in Detroit, An Afternoon in Waterloo Park. He called it a “narrative poem.” It is about a family, his family—a story of life, daily life, and change and death. It starts with the death of his mother, but Jerry contemplates three generations of his family—his, his parents’ and his grandparents’.

The book jacket reads: “It is in the complex story of this family, recollected from the surface of childhood, pondered from the depths of mature experience, that the author achieves his strength.” I haven’t read the whole thing, but I’ve dipped in here and there over the years since I acquired it, and I’ve found, here and there, things I like a lot. Here, I’ll show you some of them.

About the Supreme Being, Jerry wrote:

I wonder how many people in this church believe in God.

Really believe.

Half? Three quarters? The same proportions, perhaps,

As for all people everywhere

Outside these walls.

Faith, hope, reason, and the easiest of these is reason. ...

And what is true of what the Planner wants of you and me?

We do not agree on that. There are conflicting thoughts. ...

Has the message as it’s been passed been garbled,

Due to mumbling? ...

In the meantime there exists among believers

A bothersome mist of fine confusion here;

So a lot of people are simply being kind

And figure to play the rest of it by ear.

Once Jerry watched his grandmother as she watched her just departed husband being lowered into the earth.

They had been together fifty-five years.

Oma [the grandmother] said later she would gladly

Have died the same day. She had eleven years to wait,

And all the winters were in Detroit.

I learned that day that all marriages end sadly.

In case that one slipped by you: marriages end sadly because they end in the death of one of the partners.

In another place in the poem, Jerry writes:

I see in mind’s eye an epitaph

For a gravestone—not hers—mine, perhaps.

The bottom line reads:

Well, That Didn’t Take Very Long.