In late 2014, I was asked to contribute an essay to a book/catalogue that would accompany a museum-touring exhibition of original EC comic art. My topic was EC’s horror comics, with a concentration on the genre’s master artist, Graham (“Ghastly”) Ingels.

But the tour didn’t happen. And while there will be an exhibition (“Aliens, Monsters, and Madmen,” opening May 13, in Eugene, Oregon, at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art), there will be no book.

So here is what I wrote.

As this volume’s only contributor to have actually read – and suffered the loss of EC comics – as a kid, I feel the weight of a generation – well, a thin, weird slice of a generation – on my shoulders. Like the one alone, you know, escaped to tell you. Like the last surviving veteran of a momentous battle, though this battle’s heart-wrenching outcome, the gutting of EC following the imposition of the Comic Code of 1954, was worth only two square inches in the local press. (I retain the Philadelphia Bulletin’s actual story, preserved behind Scotch tape on blotting paper, as a personally tailored flagellant if you doubt me.)

As this volume’s only contributor to have actually read – and suffered the loss of EC comics – as a kid, I feel the weight of a generation – well, a thin, weird slice of a generation – on my shoulders. Like the one alone, you know, escaped to tell you. Like the last surviving veteran of a momentous battle, though this battle’s heart-wrenching outcome, the gutting of EC following the imposition of the Comic Code of 1954, was worth only two square inches in the local press. (I retain the Philadelphia Bulletin’s actual story, preserved behind Scotch tape on blotting paper, as a personally tailored flagellant if you doubt me.)

It was a perhaps self-defensive conceit at EC that their comics were so text-heavy they would not appeal to anyone younger and more vulnerable than fourteen-year-olds. This belief was misguided. My friends and I, who numbered among EC’s 25,000 actual card-carrying Fan-Addicts, had been hooked since aged in single digits. Some of us, (me included), had parents who forbade us to buy certain particularly transgressive EC’s – which did not prevent our devouring them in the bedrooms of our fellows whose parents tolerated greater deviance. We had grade school teachers (me, again) who commented on our report cards that our reading habits needed guidance toward “more uplifting” literature. And everyone last one of us was the concern of psychiatrists, psychologists, and an entire Unites States Senate investigating committee who sought to save us from a life of crime that these comics – most particularly these HORROR COMICS – would condemn us..

Max Garden, Davey Peters, Fletcher Sparrow, Howie Fratkin, Stu Kimmelman and I considered this absurd. We might have had no idea what our destinies would actually be, but we knew it was not crime. (Okay, for one – maybe two – of us, it kinda was. But we also turned out that many attorneys.) Our most felonious acts were stuffing the empty soda bottles stacked besides Llamar’s Drug’s pinball machines into our school bags and re-redeeming them there the following afternoon. (These proceeds we often spent on ECs.) We also knew that ECs were the BEST COMICS EVER. And our parents and teachers and congressional representatives’ ignorance of this fact provided our first inkling that those with authority over us, when it came to our best interests, might not know asses from elbows – or, a few years later, southeast Asia from quicksand. Not to mention that censorship, as a concept of social betterment, was pigshit.

Another conceit among EC defenders was that their horror stories were so over-the-top that readers were drawn to them for their “tongue-in-cheek” quality. (“Black humor,” EC’s publisher, Bill Gaines called it.) Well, hey, I was there; and if we had wanted laughs, we had Little Lulu.

The Senate had that much right. We came to EC for SEX and VIOLENCE.

I

In EC’s horror comics, people died by acid and axe, bubonic plague, electric chair, firing squad, gas chamber, ice pick, iron maiden, leprosy, meat grinder, poison dart, spider bite, straight razor, and stretch rack. People were dropped from planes, stomped by elephants, broiled, deep fried, barbecued, ground into sausage, strangled, sliced in half, devoured by crocodiles, dogs, lions, pirana, rats, sharks, tapeworms, and wolves, buried alive, crushed in machinery, flattened by steamrollers, had eyes burnt out, ears burned off, tongues severed, and entire faces torn from their cranial bones. Husbands killed wives; wives killed husbands; both killed and were killed by each others’ lovers. Parents killed children, and children killed parents, nannies, kindly old neighbors, and each other. Brothers killed sisters, and sisters killed brothers. People killed for love and money and career advancement, and when they were done they laid the body parts that resulted in display cabinets and used eye balls for golf and heads for bowling, and crocheted veins and arteries, eyelids and fingernails into tapestries for art dealers to sell. (Now there’s a metaphor for horror comics if I ever read one.)

It wasn’t simply the fact and variety of the deaths, it was their portrayal. When it came to guts and gore, nowhere in popular culture did artists have such license. Movies had had their content regulated for twenty years. Television was even more straight-laced. But the EC artists could go beyond anything that was elsewhere available to their readers. We saw rib cages exposed and eye balls dangling and blood vessels raw and spouting.

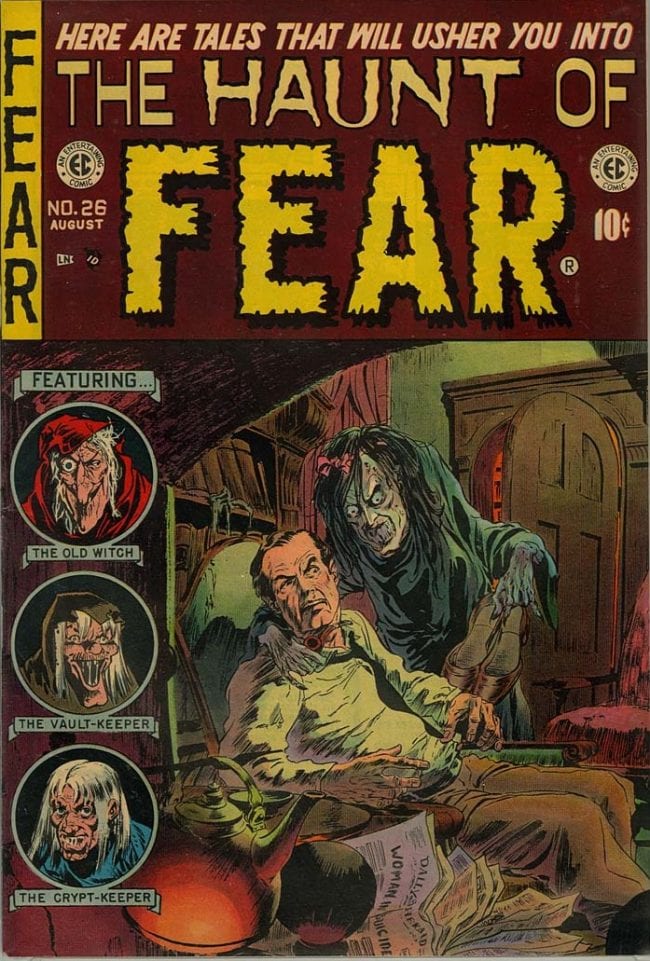

The sex was not as obvious. It well may have meant more to the mid-teen members of EC’s reading public than to my peers and me, but we knew something was going on. (At this point, Max Garden, alone among us, had parents who’d explained The Facts of Life; and while, as he later revealed, he’d paid close attention, he couldn’t imagine why anyone would actually do this.) EC’s female characters, whether murderers or murderees, was generally pin-up calendar ready. Adultery – implied, not explicit – was a frequent theme and, since regularly punishable by death, suggested something serious was at stake. Marriages were “consummated” (HOF 43) – whatever that meant. A handsome young man felt debased by having spent months “making love” – Hmmm? – to a crone in order to get her fortune (TFC 46). Sex could come across as joke-y, like in “Creep Course” (HOF 23), when the panel in which a college girl, planning to seduce a shy professor, reflects she will need to bring in her “big guns,” focused directly on her bosom. Or sex could revel in the kinky, as in “Return“ (TFC 27), when a woman is impregnated by a man who, she discovers, has been dead for years. Or in “The Handler,” (TFC 36) where a vengeful mortician buries an old maid with “parts of an old man (so that)... (t)here she lay being made cold love to by hidden hands and things. (emp. supp.)” And in my favorite, “Spoiled,” (HOF 26), when an unfaithful wife and her lover awake from a drugged sleep to find her surgeon husband has transplanted her head onto his body and vice-versa.

We might have been poorly informed. But our minds were set thinking. And our “other things” tingling.

II

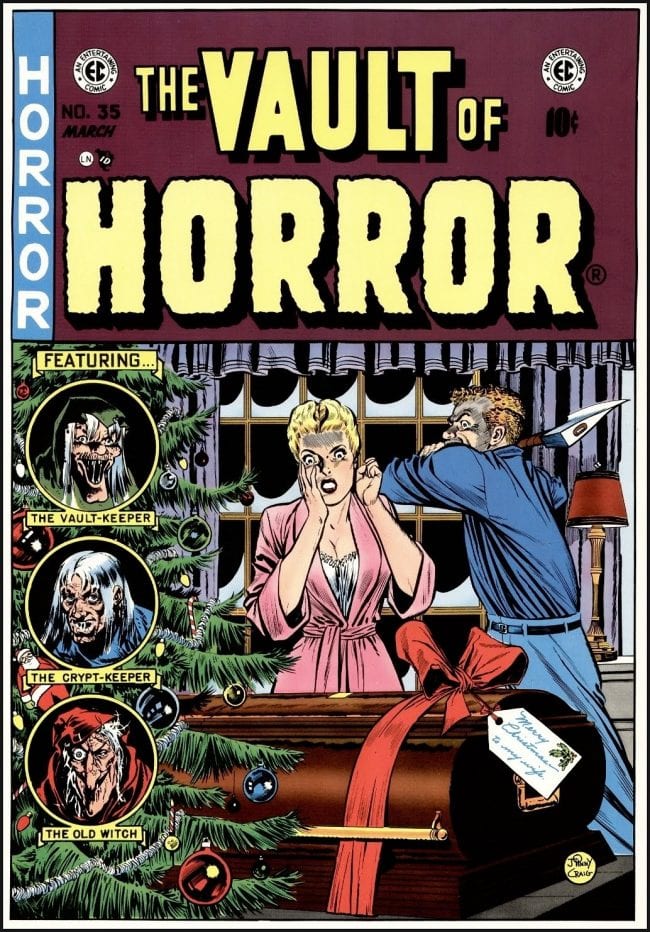

EC invented [Editor's note: Bob is aware of the debate surrounding EC's timing in the evolution of the horror comic book.] the horror comic in 1950. Al Feldstein, the 24-year-old writer/illustrator, whose idea it was, had been a fan of the radio shows The Witch’s Tale, Inner Sanctum, and Lights Out. So had Bill Gaines, the company’s 28-year-old owner. The reception for the trial stories the two men ran in other EC books, led to The Crypt of Terror (later, Tales From the Crypt), The Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. Their sales, which topped 400,000 copies per issue, made them the company’s most successful. The rest of the industry, seeking similar success, rushed out more than 700 different horror titles. None matched EC in quality or sales.

Each EC horror comic appeared six times a year. Each held four six-to-eight-page stories, with eye (and ear) catching titles, like “The Sliceman Cometh” and “Warts So Horrible.” And each, like the radio shows, had a host. The Crypt Keeper, Vault Keeper, and Old Witch, introduced, wrapped-up and goosed along the opening and concluding stories (or, as they might call them, “mess of moldy morbidity” or “reeking recipe of revolting revelry”) in their own book and guest-appeared in the others’. The Crypt Keeper’s rendering eventually was assigned to Jack Davis. Davis had joined EC in 1950, at 26. He was from Atlanta, had attended the University of Georgia on the G.I. Bill, and apprenticed on the newspaper strip “Mark Trail.” The Vault Keeper fell to Johnny Craig, a New York native and World War II combat veteran. He was two years Davis’s junior but had been drawing comics professionally since he was 12. And The Old Witch was entrusted to Graham Ingels.

Ingels was born June 7, 1915, in Cincinnati. He had dropped out of school, at 14, to help support his family, following the death of his father, a commercial artist. He worked odd jobs, from window washing to illustrating pulp magazines. In 1943, he joined the Navy. Unable to find magazine work following his discharge, he had moved into comics, coming to EC in 1948.

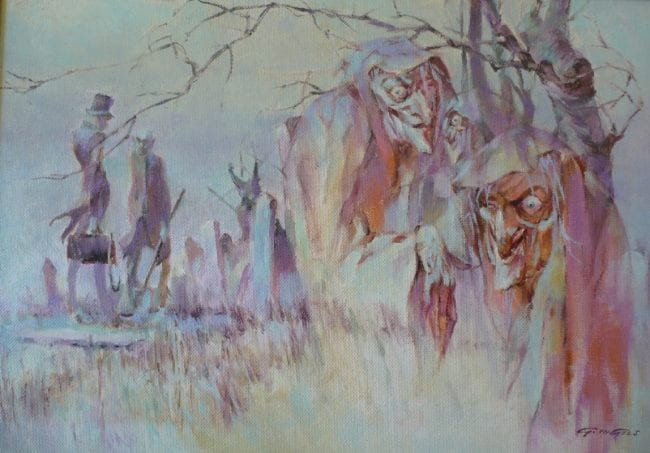

Ingels’ official EC bio described him as “shy, gentle, mild-mannered, blonde, blue-eyed.” He lived on Long Island. A Catholic, he had been married since 1935. He had a 14-year-old daughter and five-year-old son. He drove a Dodge. He was a fan of boxing and auto racing. His hobbies were fishing and oil painting. He hoped, in fact, for a career in fine arts. He burned the comics he received from EC in a fire pit in the family’s back yard.

At EC, colleagues regarded Ingels as “very normal,” “serious and hard-working,” “good natured,” “philosophical,” and, at times, “the greatest guy in the world.” He was also an alcoholic, who would disappear for days at a time, forcing Gaines and Feldstein to set his deadlines a week before his pages were actually due in order to have them when needed. His earliest – and essentially undistinguished – work for EC had been in its western and romance books. But with horror, he came into his own. He would illustrate more horror stories (82) than any other EC artist. He would do another 15 Old Witch stories for Crime SuspenS, and 11 covers for Haunt of Fear, demonstrating such a mastery that he, alone among EC’s staff, acquired a nickname, with which he would come to sign his work: “Ghastly.”

In EC’s, early years, until free-lancers became regularly employed, a comic’s editor wrote its stories. But though Craig was listed as Vault’s editor, he only wrote his own. Feldstein wrote the rest. He also wrote Haunt, Crypt, and ECs crime and sci-fi books, which meant he wrote nearly a story a day. His output was assisted by Gaines, whose Dexedrine-rich diet pills kept him up nights devouring pulp fiction, from which he filched ideas for development. EC also adapted, usually uncredited, Ambrose Bierce, Ray Bradbury, John Collier, William Faulkner, H.P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Brothers Grimm. The resulting stories were more literate, more startling (because of EC’s signature “snap-ending”)s, and, infused with Feldstein’s liberal social consciousness, more thought-provoking than the rest of the industry’s. Both Gaines and Feldstein admired good writing and recognized that the better the scaffolding they provided, the better would be their artists’ final construction.

And when it came to artists, EC proved equally appreciative. It paid top dollar, and it provided a creative atmosphere in which to work. Most importantly, EC did not confine artists to a “house style,” but encouraged them to develop their personal one. Feldstein would present artists pages, whose panels and text were in place, and would describe the action for the artists; but they were free to fill the panels with what their vision demanded. And he wrote each story with a specific artist in mind. For Jack Kamen, he wrote sexy ladies and smut in the suburbs. George Evans got nebishes in grisly situations. Davis got those where humor most obviously cackled. And Ingels received “the ooky monsters, slobbering blobs of protoplasm, and messed up old people,” “the real yuch stuff.”

III

Of the three EC host horror artists, my gang fancied Johnny Craig least. Craig worked too clean. His world was too orderly, too neat. His panels left too much space for an eye to calm within. His blondes could have been cast by Alfred Hitchcock. His werewolves, with visits to a barber and cosmetic dentist, could tidy into an Arrow Shirt model. Craig was a notoriously slow worker, taking a week to write his story and two to draw it; and that methodical approach seemed to have leached all the spontaneity from it. Even Davis later said his work “was beautifully done, but it was never scary.”

Craig created great covers though. Vault 35's horrified wife confronting the Christmas coffin, gift-ribboned for her beneath the tree, while, from behind, her husband swings his axe, demanded we possess it, hide behind locked doors, and ponder its details. And Vault 30 may have been EC horror encapsulated. An arm, severed at the elbow, radius protruding, blood dripping, clutches a subway car strap, while seated passengers seemingly glimpse it simultaneously, react, and, at the car’s end, an advertising placard inquires, “STOMACH UPSET?”

Jack Davis drew superb covers too. From his debut madman nailing shut a blood-soaked coffin (TOC 29) through his fearsome werewolf finale (TOC 46), he set Crypts flying off the stands. Both it and Craig’s Vaults outsold Ingels’ Haunts. Their bold covers attracted more customers than his more nuanced – if “nuanced” is the right word for covers replete with bodies slung over shoulders and gelatinous blobs rising from basement floors to clutch a fetching woman’s bare leg.

And Davis was a terrific illustrator. He churned out pages rapidly, even exuberantly, and his hairy, sweaty, bulge-eyed monstrosities suited Feldstein’s over-heated, modifier-soaked prose. Davis’s almost slap-stick abandon fit the punch-line humor of “Country Clubbing” (HOF 23), in which an escaped convict, who bashes in an old woman’s skull, flees into a sanity-snapping swamp to avoid her ogreish son who, it turns out, only meant to return his club, as well as the near-shaggy-doggish “Who Doughnut” (VH 30), where a multitude of blood-drained victims turn out to have been slain by a vampire-octopus. And in sheer grotesqueness, Davis’s rotting corpses surely exposed more bone, dripped more flesh, and dribbled more brain matter than those of any other contender.

And Davis was a terrific illustrator. He churned out pages rapidly, even exuberantly, and his hairy, sweaty, bulge-eyed monstrosities suited Feldstein’s over-heated, modifier-soaked prose. Davis’s almost slap-stick abandon fit the punch-line humor of “Country Clubbing” (HOF 23), in which an escaped convict, who bashes in an old woman’s skull, flees into a sanity-snapping swamp to avoid her ogreish son who, it turns out, only meant to return his club, as well as the near-shaggy-doggish “Who Doughnut” (VH 30), where a multitude of blood-drained victims turn out to have been slain by a vampire-octopus. And in sheer grotesqueness, Davis’s rotting corpses surely exposed more bone, dripped more flesh, and dribbled more brain matter than those of any other contender.

Davis’s most notorious work was “Foul Play” (HOF 19), at whose conclusion an evil baseball player has been dissected and recycled, his head a ball, one leg a bat, his heart home plate. Fredric Wertham, M.D., horror comics leading critic led off his illustrations in Seduction of the Innocent, the tome that triggered the senate investigation, with its concluding panels. Even EC stalwarts ran from it. Feldstein called it “an atrocity.” And Gaines termed it, “One of our worst... It was a stupid story. It was certainly in bad taste. And I’m sorry we did it...” Even Davis confessed that, after Wertham’s attack, “I wanted to bury my head. I wished I never did it.”

Davis’s most notorious work was “Foul Play” (HOF 19), at whose conclusion an evil baseball player has been dissected and recycled, his head a ball, one leg a bat, his heart home plate. Fredric Wertham, M.D., horror comics leading critic led off his illustrations in Seduction of the Innocent, the tome that triggered the senate investigation, with its concluding panels. Even EC stalwarts ran from it. Feldstein called it “an atrocity.” And Gaines termed it, “One of our worst... It was a stupid story. It was certainly in bad taste. And I’m sorry we did it...” Even Davis confessed that, after Wertham’s attack, “I wanted to bury my head. I wished I never did it.”

But, hey, Jack, no apologies, no regrets. Who ever said art required good taste? The grand and glorious thing about comics was their defiance of church and state and the poo-bahs of propriety. EC taught the value of digging within yourself and airing what you found – even if that meant laying your intestines to mark your base lines.

If Davis had a problem, it was not the depths he plunged but the adaptability he showed. His style slid so easily into too so many genres, you could not be sure he ever gave his honest all. He did horror. He did war. He did cowboys. He did MAD. It always felt Davis was performing, like The Crypt Keeper was just one more assignment he drew. But Graham Ingels’s style seemed devoted to horror. Horror seemed a part of him, and he a part of it. The Old Witch merged with Ingels in our thoughts. He seemed to invest an essence in her. His work was, Feldstein later said, “a product of his total make-up – his personal, psychological, emotional make-up.”

Gaines would call Ingels “Mr. Horror.” Stephen King saluted him in his short story “The Boogeyman,” for his ability to “draw every god-awful thing in the world – and some out of it.” The cartoonist Jim Woodring once considered Ingels’ work “the product of a diseased mind or something” And me, in retrospect, I fingered him as “The Little Richard of Comics.” I mean, when rock’n’roll came in, if you were in a car, with your parents, and the radio station you’d selected erupted with “A-wop-boppa-loo-mop. A-wop-bam-boom,” your taste – your intelligence – your entire way of being became suspect. Same with Ingels and comics. His work caught you the most evil-eyed, purse-mouthed grief.

In Ingels’ world men were weak or avaricious, imbecilic or maniacal, and women sluts or hags. They populated fetid swamps, decaying mansions, moldering dungeons. Their bodies drooped and distended; their features melted and dissolved; their muscles strained agonizingly; their limbs angled impossibly. Every part of them reflected horror. They bore bony, elongated, clawed fingers, over-sized, over-sharp teeth, lust-filled, hate-filled eyes. They were regularly buried in the rain, and, from the mud, repeatedly arose, rotting, drooling, seeking revenge.

The elements scourged Ingels’panels. Blackness enveloped them. Their word balloons bore jagged edges or dripped. The lines which enclosed them, instead of imposing order, wavered. Hands groped beyond them; phones dangled past them; The Old Witch’s warted chin drooped over their edge. Faces spun within them: on one side in one; straight up in the next; on the opposite side in the third. Long shot alternated with close-up. Points-of-view shifted, from floor to ceiling. The viewer lost hold on the ordinary. There was no solidarity, no consistency, no principle to cling to. Everything decomposed – like those corpses seeking revenge.

Ingels’s most celebrated story is “Horror We? How’s Bayou?” Certainly, Feldstein deserves an assist, for his script presented the artist, not one, but three vengeful corpses to render and, not any three corpses, but two male and one female, all of whom have been dismembered and mixed-and-matched when restored. Their bodily lesions, facial cavities, mis-grafted limbs, and mis-aligned bony protuberances were chilling, but one simpler portrait gripped me more.

The story opens in shadows and darkness. Max Forman, a motorist lost in a swamp, enters an “old..., weather-beaten...faded” mansion The owner, Sidney, demented and threatening in appearance, invites him in – and makes Forman the latest victim fed the swamp. When these victims return for Sidney, they fulfill all expectations for the hideous, but it is his reaction, when they breach his bedroom that chills (p. 6, TR). His head floats alone, within a vortex of decapitating black lines, these lines merging into his representation. His eyes hunt for an escape from his skull. His mouth, twisted and torn, utters “Oh, Lord...” Terror has turned him more grotesque than the creatures who will have their way with him. Bill Mason, an unsurpassed Ingels admirer, once wrote that his, “greatest achievement... was the depiction of the face of horror,” and HWHB makes that assessment hard to dispute.

But it was Ingels’s interpretation of Otto Binder’s “The New Arrival” (HOF 25), which embedded itself most deeply into my brain. Again, there was a stranger, Edgar Lockwood, lost in a swamp, seeking aid within a stormy night, again “an old, dilapidated, weather-beaten, paint-starved, once-proud mansion.” This time there are no corpses though, and the elderly widow, Cynthia Ackroyd, who answers the door, is pleasant in appearance.

But she has a sick and crying baby she will not let Lockwood see. And she seems to old a baby and its cries too loud and its toys too large. When Lockwood investigates, he finds a dying middle-aged man, chained to his bed, diseased in body and mind, imprisoned since infancy. Mrs. Ackroyd clubs Lockwood unconscious and, when he awakes, in the final panel, he bears the chains, lying cradled in her lap, while she offers him a bottle and croons, “The Cradle May Rock.”

I spent much time in the following years wondering if and how Lockwood got out. His fate disturbed me more than that of those chopped and diced and ground into burgers. My wife, the supremely insightful Adele, has pointed out that aligning with ECs provided kids a way to separate from their families and begin to establish their own personal identities. Now, reviewing Ingels’s work, I saw this story in that light. I saw myself identify with Lockwood’s plight. Could he ever escape? Could I? Were we both doomed to remain under the control of more powerful creatures, descending into decrepitude with them?

And then I considered Bill Spicer’s finding (VOH 12) that the second most common cause of death in ECs stories was suffocation. These stories had been written by men who, like Ingels, had grown up in the Depression and served in the war. Like him, they’d aspired to scale the artistic ladder, of which comics were the bottom rung. But they needed comics, for, again like Ingels, they had a wife, a family, a suburban home. Trapped, I thought. Suffocating.

The most common cause of EC death was those rotted corpses. And what were they, I thought, but these artists’ and writers’ repressed selves exacting revenge for their entombments.

IV

“Graham Ingels was)... one of the most mysterious figures in the EC pantheon.” -S.C. Ringgenberg

“Who knew what went on in Graham’s head...” - Al Feldstein

After the Comic Code’s imposition, Ingels found himself practically “unemployable.” He drew comics briefly for Classics Illustrated and the Catholic Church. He joined the faculty of the Famous Artists School, in Westport, Connecticut, instructing students by mail. Then, in 1962, he abandoned his family and, as far it – or the comic world knew – “disappeared.” “We were used to his leaving,” Ingles’s son recalls, “and one day he left and never came back.” Ingles’ wife found work as a secretary and his daughter with the Catholic church. His son delivered newspapers and raked leaves.

In 1972, it became known that Ingels was living in a small town in Florida, painting and giving private art lessons. He was said to be “extremely reclusive.” He was said to have become “increasingly troubled by the horror genre, and, even more so... by his special knack for it.” He threatened fans who wished to visit him with litigation. He insisted all communications come through his attorney. He declined all invitations to conventions. (When EC fans voted Ingels Best Horror Artist and HWHB Best Horror Art, Gaines accepted the awards for him, but it was unknown if Ingels ever took possession) He refused interview requests. He refused commissions. He refused to do the poster for the movie Creep Show. He refused a publisher’s offer of a free, slip-cased, coffee-table-sized five volume reprint of Haunt of Fear. (He accepted a Crime SuspenStories set instead.) When Gaines auctioned the original EC artwork, he had to argue Ingels into accepting his share of the proceeds. Shortly before his death from cancer in 1991, Ingels painted several re-imaginings of The Old Witch, the largest of which sold for $7500. But the picture left of Ingels has been that of an estranged, haunted, even tragic figure.

But that picture is untrue.

Lantana, the town in which Ingels settled, is on Florida’s southeast coast. It had about 5000 residents, and its most noteworthy site was a TB hospital. It was 50 miles from Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades, with its complex of marsh, forest and, fittingly for Ingels, swamp. They had been the home to unsurrendered Native Americans, runaway slaves, hunters of egret plumes and alligator hides, mangrove loggers, cattle ranchers, rum runners, and sugarcane growers. Undeveloped until the 1920s, it had been the country’s Last Frontier. But Ingels had not gone there to disappear but to create that rare thing among American artists a Second Act.

He had not come alone. While in the northeast, he had become involved with Dorothy Bennett, a classically trained pianist. When Ingels’ wife refused him a divorce, he and Bennett left together. They moved into adjoining houses in Lantana, he in one and she and her mother in the other. After Bennett’s mother died, he moved in with her. He stopped drinking. He reconciled with his daughter. He immersed himself in learning South Florida’s history. He outfitted an old Ford van with bunks, bathroom and kitchen, and, each summer, he and Dorothy motored to his cabin in Maine farm country, close to woods.

Ingels taught art classes, twice a week, for as many as 14 pupils at a time, young and old, male and female, well-off and not-so, beginners and advanced. He did portraits of the wealthy and the influential, Seminoles and cowboys. He did paintings of sail boats and Dusenbergs. He carved three-foot-tall wood sculptures and painted a 200-foot montage of the history of the Everglades. His students adored him. They found his work important and him inspirational. He received commissions and sold through local galleries but, according to Bruce Webber, who owned one, because he kept himself apart, never achieved the success his work deserved.

He never mentioned his work in comics. Toward the end of his life, one of his students, Ann Tyler, now 76, who had come to Ingels a self-described “little country mouse” who hoped to paint, and become a close friend, as well as a successful painter, now known as “The Artist of the Glades,” walked into his studio, while he was working on a picture of a Red Witch. “My mouth fell open,” she says. “I LOVED IT!!!” But he would say only that she was “A good witch.”

Tyler does not believe Ingels was “troubled” by his work for EC. But she believes him angered by society’s having scapegoated horror comics as responsible for some of its ills and hurt by the comic industry’s rejection of him for his association with these books. “But he came down here and found a whole life he liked and found work in the fine arts that showed his talent and found a lot of people who loved him.

“I thank the Lord for all the years I had with him. He changed my life. He certainly did”

Footnotes Notes

All references to EC comics are to the hardbound, slip-cased, multi-volume Russ Cochran, Publisher edition. They are identified RCP, followed by the particular comic’s abbreviated title. These volumes contained commentary and interviews, which were not paginated, so I have had to locate them otherwise.