[This is the second of a two part series. The first part is here.]

Carol Tyler: I lived in California and I had made friends with Aline Crumb and Diane Noomin, especially Aline because we were somewhat neighbors. I had met her at a party at Ron Turner’s. I met a bunch of people there, including Mary Fleener and Trina. I met so many people through Ron Turner and through that scene. I was married to Justin [Green], but he didn’t want to do any socializing, so I went ahead and forced myself on people because he didn’t want to. That’s how I met everybody. Aline and I became friends. Our kids played together. We shared holidays. Aline saw my work and invited me to submit to Weirdo. She published some things, and so people knew I could do a page or a couple of pages. Dana Andre (Mark Burbey) asked me to submit to Street Music, and Trina invited me to Wimmen’s. The thing is, with undergrounds and alternatives, you’re talking about a very small pond. What options did you have to get published back then? It’s not like the internet today where you can post something on-line and get 200 likes. That world had a limited readership. I wasn’t even getting published until 1987, so I’m not one of the original underground comix pioneers, although I’m of that age group.

Leslie Ewing: I had been doing a strip called “Mid-Dyke Crisis” in the mid ‘80s and was one of maybe half a dozen women drawing cartoons that were specific to lesbian lives. I probably saw a call for submissions notice in a local community paper and simply submitted a story. I came on fairly late into the process. I was just starting out really and appreciated the mentorship and support, which I received mostly because I lived in the San Francisco Bay area and could make the “collective’s” meetings, usually held in living rooms and cafes.

Mary Fleener: I saw it reviewed somewhere, and sent a letter to Last Gasp asking if I could submit something to the next issue. A year later I got a letter from Joyce Farmer informing me that she was the editor for “The Politically Incorrect Issue.” I think that was issue #10. I sent her “Madame X From Planet Sex.” I'd only self published mini comics and my stuff was in a few zines, but not a comix with any name recognition or distribution, so to be published in Wimmen’s right away was encouraging, of course. Joyce Farmer lived in Southern California like myself, so I was able to meet her, and discovered Tits and Clits, and that was pretty great. We ended up working on the last issue together.

Phoebe Gloeckner: I was young, relative to a lot of the other people in the group at that time. Most of the others were ten or fifteen years older than me. I wasn’t amongst the founders of the title. I was looking at it from a different perspective and so I just knew it as one of the only places where women could easily get published. Although it was a solution, it also amplified the problem. The editorial process didn’t seem all that discriminating. There was plenty of good work in Wimmen's Comix but it was spotty. This was a quality shared by most underground publications. Not all the work was good, but many of those who continued to do comics–and good comics–were first published in Wimmens Comix. Of course, the variety of style, subject, and, indeed, quality is what made the undergrounds exciting.It’s hard to find that now because things don’t seem to work that way. Comics now are usually are more selective, editors have personal standards for inclusion and acceptance. But that doesn’t always result in “sparky,” exciting, invigorating reading.

Roberta Gregory: I went up to the Bay Area a couple of times to visit the Wimmen's Comix “wimmen” but I didn't really feel all that much different than them. I wanted so much to move up to the Bay Area, even going so far as to apply for jobs there, but it never seemed to work out. I think of it to this day as my “real” home. But I also made friends with Joyce Farmer and Lyn Chevli, who published several comics under their Nanny Goat Productions imprint in Southern California, and they were a big help and inspiration to me. I think their Tits and Clits first issue came out just a bit before the first Wimmen's Comix, if one wants to sound competitive, but there were so many wonderful creative breakthroughs for women in the 1970s, culture, music, arts, any possible boundaries never seemed to matter.

Shary Flenniken: Becky Wilson [who co-edited #6] asked me to do something and I was like oh, color, that’s fun and I can just do a one off joke? I was in other comics when people invited me. I did a sex education comic for Lora Fountain. She’s a wonderful person and she was very involved in important issues.

Jennifer Camper: Each issue had different editors, and a theme, which could be interpreted broadly. I was contacted by the editor by mail. The only guidelines I recall were the page size and a deadline, I suppose it was implied that the work shouldn’t be sexist or racist or stupid. I mailed in veloxes of my work. We signed contracts from Rip Off Press, and the page rate was $25.

Leslie Ewing: The experience provided an opportunity to learn how to create comics that could either be funny first and activist second–or, the other way around, depending on the situation. The experience helped me solidify my identity as an activist cartoonist.

Mary Fleener: This was in the pre-Internet Age, so everyone wrote letters and postcards and everyone talked on the phone a lot, and as a result, you get to know people. That was the best thing I got from being in Wimmen’s, meeting whomever was the editor for that particular issue. Even though the hub and scene was in San Francisco, I felt like I was part of something that was exciting and interesting.

Caryn Leschen: I came out [to the Bay Area] and I found out about a thing called “The Loonies,” which was every month at a bar for years. I met Trina Robbins and Lee Marrs and all these people whose comics I had read. They were very inviting and so I was invited into issue #8 which was a little bit of a revival. Two years had gone by since the previous issue. That was 1983. I wanted to learn more about comics and making books and publishing and editing so I volunteered to be an editor of issue #9. Then I was the editor of another. It would force me to read. I was very interested in what people were doing. Wimmen’s was a kind of paying it forward thing. I wouldn’t print stuff that was crap, but I would work with people to see if I could get something really good.

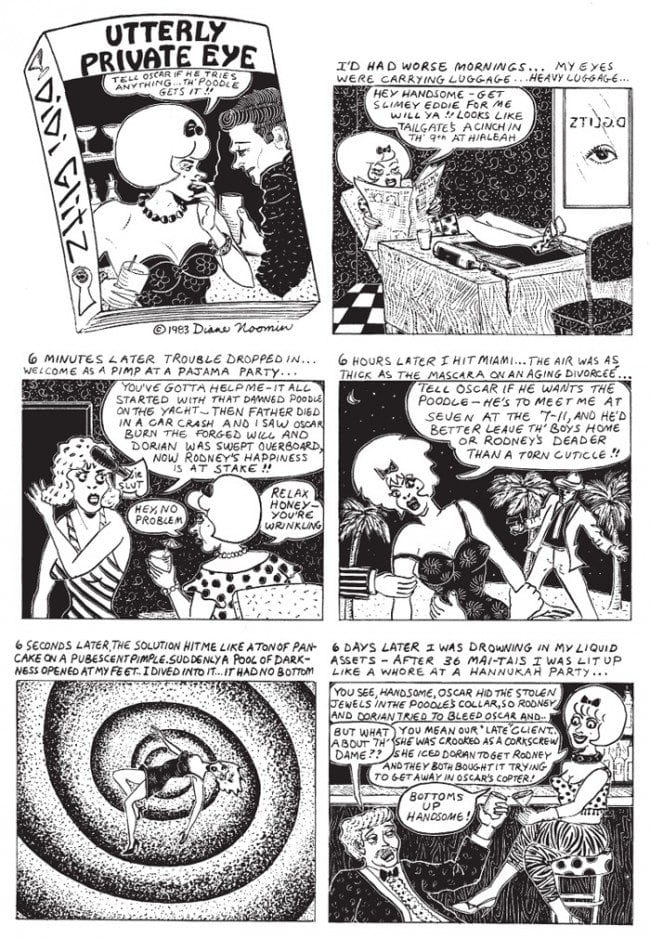

Diane Noomin: I returned to Wimmen’s Comix after eight years, for issue #9 in 1984, which was edited by Lee Marrs. Lee was above the petty bitchiness that had turned me away earlier. The following year in Issue #10–“The Politically Incorrect Fetish Issue”–edited by Joyce Farmer, I did a 2 page story, “Rubberware.” This was followed by Issue #11, the Fashion issue, in 1987, edited by Dori Seda and Krystine Kryttre, which I did the cover for. After that, I had stories in most of the remaining issues.

Jennifer Camper: I read most of the early issues of Wimmen’s Comix, and then, after I began drawing comics more seriously, I submitted comics for issues 14 and 17. Wimmen’s Comix, Tits and Clits, and the work of Mary Wings and Roberta Gregory were the comics I read as a teenager, and it helped form my idea of how comics could be made, and how women could make comics. While I also read the male underground comics, the women’s work was more interesting and exciting to me.

Roberta Gregory: I think I really noted that all the contributors had very different drawing styles. Most of the comics I had been reading all seemed to be done in a certain style, all the Archie Comics had a certain “look” and my father penciled Disney comics at home, and he had to imitate certain styles for Donald Duck, and so on. A lot of the underground comix artists seemed to be trying to imitate Crumb. But the women in Wimmen's seemed free to draw however they wished. There were even contributors who did not draw well at all, and that didn't stop them from telling their stories. Many of the stories seemed to be about real life, sometimes even autobiographical, and that was very appealing, too. I don't know how much of that was done before Wimmen's Comix.

Joan Hilty: I was aware of it because I had been picking up various underground comics–Wimmen’s Comix, Gay Comix, Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers–that still circulated at that time. I was the last wave of people to contribute to it and yet I wasn’t that aware of the history. That like Tits and Clits it had been founded to provide a showcase for all these great women cartoonists and to push back against some of the inherent sexism that was happening in underground comics. I just knew that it was great storytelling and I wanted to be a part of that. I think that might have been my second or third publishing experience.

Caryn Leschen: I had done a couple of things before Wimmen’s Comix for magazines and just for myself. For Wimmen’s Comix I did a story called “Holding a Torch” which was very, very busy. I was like, nobody’s ever going to want me to do a comic again so I’d better put every single thing I know how to do into this one comic. It’s not bad. If it were the size of a billboard it wouldn’t look so crowded. [laughs] I also realized that it took me a really long time. It just took too long to do the parts that were hard, so I decided to go to art school. I got a huge amount of confidence from graduating art school. I went when I was 29 and graduated when I was 33. It was a privilege and I learned a lot.

Phoebe Gloeckner: I didn’t come from hippie culture, but Underground Comics arose during the Hippie Era and I loved them. I was more of a punk when I began getting work published, doing stories for RE/Search and other punk tabloids in the Bay Area. I never expected anyone to have read my stories published in Wimmen’s. You’re one of the first people who ever said, “Hey, you were in Wimmen’s Comix.” It was a safe place for me to show work because I was creating stories that I wouldn’t have felt comfortable having many people read. It was a way to get published without being seen. [laughs] Which is kind of ironic. Whether the work was read or not, being published made me feel good and it gave me a goal. It kept me working, helped me build a body of work and figure out what I wanted to do. Part of the impetus for doing comics was that I had friends in the group. If I dragged my ass, I’d feel like a jerk.

Joan Hilty: I grew up in the San Francisco Bay area and I had just moved back to the Bay Area from Rhode Island, where I went to school. When I did, I looked up Trina Robbins. I took a cartooning class from her at a community college in Marin County when I was eleven or twelve. She really is my most important mentor in comics because I took that class and it lit me up and helped keep me interested in cartooning at a very young age. I stayed aware of who she was and what she was publishing. I knew after college that I wanted to continue drawing comics. I’d drawn a comic strip for the college paper and I wanted to start doing it professionally so I looked her up and asked if I could talk to her about the business. That was probably 1990. She said, come to the Wimmen’s Comix collective meeting and you can be in one of our issues. So I did. It was a brief period and I only attended like two meetings and got into that one issue but it was terrific. Trina had been very welcoming to me and very supportive and just instantly took me in. I remember meeting Diane Noomin and Caryn Leschen. I think one meeting was at Trina’s house and another was at Diane’s house. I was the younger generation, but they were all extremely welcoming to me. They were just very inclusive.

Jennifer Camper: In the '80s, underground comics had finally grown to include more women and queers, and I was just starting to seek publication for my comics then, so it was great timing. Howard Cruse created Gay Comix in 1980, and I had comics published there also. Most of the Wimmen’s Comix contributors and editors were living in the SF Bay area, and I was on the East coast, so I only met a few of the women briefly during visits. My knowledge of many of these women, and their cartooning careers and their community, was only through their art. But I had a strong sense of them supporting each other and carving out a place for themselves in comics, despite the rampant sexism.

Carol Tyler: I didn’t try to tool it in such a way that it would appeal to a woman’s audience or something like that. I’d follow the theme and try to push it past my first idea. For example, for one issue, the theme was “Disastrous Relationships.” My initial thought was “wow, a chance to beat up on the ‘ex’” but then I decided on a story about my Korean roommate trying to escape an arranged marriage to a man she did not love. I aimed for more complex stories and a multi-dimensional approach. That’s become the work I do today. I’m always trying to be a better cartoonist and tell better stories than I did before. I had a problem reading as a kid so I did not have the pleasure of books. I learned to read because I had to. It was always a struggle to read and being from the working class, there’s no reinforcement of the pleasure of reading. No time for such things! As a cartoonist and writer, I don’t want anybody to know about my deficit booksmanship, so I have to constantly push myself and up my game. I do love books, but it wasn’t part of my childhood. It was like, ‘I don’t know much past Faulkner, but I’d better by god convince people I do.’ I felt really responsible to try to pull off literacy by bluffing my way through somehow. But the idea of telling a story specifically through a woman’s lens, no, I was just hoping for a story that held up.

Caryn Leschen: I think complaining creatively is really powerful. That was the thinking behind the “kvetch” issue. I’m not that into the glorification of, oh we’re women and we’re powerful. I don’t have to explain why I’m powerful. That goes without saying. I’m a little past the generation where that had to be said, though. I’m not that first generation of feminists.

Joan Hilty: It had a significance for me because I was already out of the closet. I had come out as gay in high school. I had been politically active as a gay woman and a feminist in college. Underground comics helped me understand that there was historical precedent for me coming of age as an empowered young woman, as an out gay woman. I was publishing in gay comics, but even as Howard Cruse and Robert Triptow worked to diversify it, gay comics in general–with the exception of the Gay Comix title–were much more male focused, whereas Wimmen’s Comix was very inclusive. It was straight women it was open to gay women; it spoke to my entire experience and that was very important to me. I really can’t overemphasize how important it was to have that support.

Phoebe Gloeckner: There were power struggles. There were those who seemed to assume ownership of the group. There were disagreements and arguments, which is ok, really—better that people feel free to voice opinions rather than be silenced. At one point, I edited an issue in which a particular story became the basis of a huge rift. I wanted to publish a Czech artist, Lucie Kalousková, who did a story about a little girl and an older man on a boat ride, touring a zoo. There were people who were offended by the story and felt strongly that we shouldn’t accept it for publication. There were tears and there were fights and there were people walking out of the room. It was a pretty stressful and emotional meeting. I was surprised by the charged response to the story. Wimmin’s Comix had always been so inclusive. We kept the story in there, but it wasn’t easy. The entire event was being filmed for a documentary about the collective, but most likely that footage was not included in the final edit. I learned that it’s hard to get along with everybody, but you just kind of have to try if you want to make a magazine. [laughs]

Carol Tyler: The thing about Wimmen’s was, apparently it was Trina’s joint. I know some stuff was going on between Aline and Diane on one side and then Trina on the other. Tension regarding intent and motivation. Coming later to the scene I didn’t have a history with either faction, but there were definitely factions. Trina and Wimmen’s had a woman’s agenda. Aline and Diane were both expressing their experiences as women, but not under the ‘woman’ banner. I think Trina was more interested in the politics of the women’s movement and rightly so. Now listen, I love Trina, I love Aline, and I love Diane. I love all these cartoonists. I don’t get it exactly what went on, but I know I got in the middle of it [laughs]. Especially after Dori Seda passed away. Ron and Trina had an idea to memorialize her with an award at Comicon in 1988. This put a lot of folks ill at ease because Dori and her best friend Kristine Kryttre–Aline published their work in Weirdo. Talk about being on the spot! From my perspective, I was just happy to be alive and working, and I loved them all. And then I got the award–Best New Female Cartoonist. From that moment on, I feel a great responsibility and have worked extra hard to live up to the honor.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: It was was a different sensibility and a different vision. All of us were strong personalities. Trina and I are both Jewish, we’re both Leos, we’re probably more similar than anyone would want to admit. We’re on cordial terms with each other now. Trina started the whole thing and she was very proprietary about it, which is understandable. Trina’s very charismatic so she had people who admired her that were very protective of her. I had my own style. I just rubbed some people the wrong way. I think it was inevitable that we would bump into each other and then go our own way. I don’t think that’s bad.

Diane Noomin: I attended one of the first meetings of the Wimmen's Comix Collective in 1972. Pat Moodian was chosen as editor and I met many of the cartoonists who wound up in the first issue. I had stories published in Issues #2 and #3. During that time, there was quite a bit of infighting which continued to get more and more vicious. Trina Robbins had a kind of “Queen Bee” attitude about her position in the “collective” partly because she had been published previously and partly due to her resentment of Aline Kominsky for her connection to Robert Crumb and her resentment of me for my connection to Bill Griffith. An example of this is this review of a San Francisco gallery show of comic art from the April 11-17, 1975 Berkeley Barb, written by one one of Trina’s followers, Sally Harms:

“Picture Stories” displayed a new twist in the suppression of women artists by promoting mediocrity in the choice of two thirds of the women represented. Diane Noomin and Aline Kominsky, the two other women artists in the show, simply have not worked their craft up to Trina’s level, or more to the point, up to the level of a good half dozen other women artists I could name.

As Trina, who is known for her outspokeness as well as her commitment to feminism put it, “These two women are camp followers. Their work is obviously crude, and they don’t have the background of Lee Marrs or Sharon Rudahl, for instance. As co-editor of the next Wimmen Comix, I’ve already rejected work that’s better than theirs. People wonder why I get so pissed, but it’s this kind of cliqueism in exhibitions, publicity and publishing that threatens the very livelihood of me and my deserving professional sisters.”

Trina Robbins: I did not know that there was tension between us until they started talking about it in print. I never personally liked their work, but that didn’t stop me from publishing them. There were some people whose work I didn’t particularly like but I was always very accepting and thinking, give them a chance and they’ll get better. But if you don’t publish them, they’ll never get better. I very naively did not know that they disliked me so much until they said it in print. In Aline’s book she and Diane have said some amazing things about how I shut them out. In 1977 I edited a British collection of Wimmen’s Comix reprints and both Diane and Aline were in it. I was the editor of that. I didn’t have to invite them. I co-edited a benefit book called Strip AIDS USA. I invited both of them into this book and Diane did contribute. I co-published and edited a pro-choice benefit book called Choices. Again I invited them both in and Diane contributed. If you look at the books that I have edited you will see that I always included them. On the other hand they never included me in their projects. I just put it down to, they just don’t like me. You can just not like someone.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: The other thing that was a factor is that I got involved with Robert [Crumb]. He was the ultimate male chauvinist pig according to some people. Then Diane got involved with Bill Griffith–not that he was a male chauvinist–but the fact that we were both involved with male cartoonists annoyed some of those feminists who were really down on men. We were strong women but we weren’t anti-sex and anti-men. In early feminism, some people were very, very doctrinaire. They wanted to almost break away from men. I never really felt that persecuted, personally, but people have different experiences.

Diane Noomin: Aline and I both felt drawn to comics that were satirical, ironic, self-deprecating and personal. The tone that the Wimmen’s Comix editors seemed to favor was, for the most part, an idealized feminism as personified by Trina Robbins’ work. Trina was an authority figure to a lot of the newer cartoonists, who seemed to follow her lead blindly. In 1976, in a break with Wimmen's Comix, Aline and I decided to combine forces and create Twisted Sisters Comics, which reflected our ideas of what comics could be. We put less stress on gender and more on personal storytelling, less on sexual politics and more on the satirical and autobiographical.

Diane Noomin: Aline and I both felt drawn to comics that were satirical, ironic, self-deprecating and personal. The tone that the Wimmen’s Comix editors seemed to favor was, for the most part, an idealized feminism as personified by Trina Robbins’ work. Trina was an authority figure to a lot of the newer cartoonists, who seemed to follow her lead blindly. In 1976, in a break with Wimmen's Comix, Aline and I decided to combine forces and create Twisted Sisters Comics, which reflected our ideas of what comics could be. We put less stress on gender and more on personal storytelling, less on sexual politics and more on the satirical and autobiographical.

Jennifer Camper: I was very influenced by the supportive atmosphere at Wimnen’s Comix. Everyone was extremely helpful and promoted each other’s work. There was not much competition, possibly because there was little money or recognition for our work. I was also influenced by these cartoonists’ drawing and writing styles and how the comics format can be constantly reinvented. When I edited the Juicy Mother anthologies, I had themes for each issue, and I made an effort to include new cartoonists–as was done in Wimmen’s Comix. I think I’m a better editor because I remember how important it is for a beginning cartoonist to receive support.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: I’m painting now. Drawn and Quarterly is going to reprint Love That Bunch in 2017. I’m working on a thirty page story that’s going to be added to it and I’m going to do a new cover. I’m a grandmother and have a very different perspective on life, but it’s still interesting writing about that.

Patricia Moodian: I would like to do a comix artwork about the wrongful and illegal practices of the child protective agencies in the United States, and expose the destruction of families and the harm to children that the agents of these government entities do with impunity, hiding behind the false veil of “protecting the privacy rights of minors,” but in actuality only protecting their own misdeeds from prosecution for their criminal acts, acts which are hidden from the view of those who would change the system if they knew how corrupt it is. Children want the world to know they are being harmed, and they want all of us to stop the cruel treatment they suffer in the hands of the government. The entire juvenile dependency system in this country is a seething mass of horror for the families and children who are its victims. I have about three thousand pages of actual dependency court transcripts of a case reversed by the appeals court that details the illegal and unconstitutional acts that happen every day in our juvenile dependency system. We need to support and keep families together with services, rather than make money and jobs through the destruction of families and the illegal removal of children from their homes. Other things I am interested working towards are to see all colleges are tuition free and all student loans are forgiven; to stop the way big money buys the politicians who create the laws and rules that make most people wage slaves without hope of bettering their lot; and to entertain and inform in a way that makes people feel better about themselves and helps them be able to laugh while they learn and grow.

Lora Fountain: I realized that drawing and writing comics wasn’t really my strong point and decided to leave it to better artists and writers than myself. At the same time, I got involved in doing video projects in Spanish and English with a women’s collective called Video Compañia and started doing more video and still photography. I edited the Marin County Heart Association’s quarterly newsletter for a while and co-wrote and produced three videos about childbirth and breast feeding (2 in Spanish and 1 with a black family), as there was no good educational material available at the time for those groups.

Lisa Lyons: I continued doing political art, and also got an MA in Art History. I was a co-founder and staff member at two Sudbury schools, one in Maine and one in Maryland, and raised three children. I was also a graphic designer, which involved a fair amount of drawing. Since retirement in 2009 and moving back to Maine, I’ve been doing a lot more cartooning, both for New Politics, a socialist journal, and for Paul Buhle’s Bohemians. Paul got me back into the world of comics, and it was an honor to be part of Bohemians. And of course, I’ve always followed Trina’s amazing career. I hope there will be more opportunities for me in comics in the future. Partly because of Trina and Paul and, of course, comics like Maus, the artistic and political possibilities of comics are wide open. Misogyny and sexism seem to be as rampant as ever, but women are so much more visible and vocal than we were when It Ain’t Me, Babe was new—thanks to women like Trina who changed the dialogue.

Barbara Mendes: Wimmen’s Comix came out and my story "Holy Parents" was rejected. I have a chip on my shoulder about Wimmen’s Comix–though my story “Kewpie the Groupie” did appear in the third issue of Wimmen's Comix. I was out of the comix movement by then; I've been exhibiting paintings since 1973. But now, I’m ready to jump back in! When Professor Robert Lovejoy called me in December of 2015 to inform me that page 1 of “Realm of Karma Comix” from All Girl Thrills, is to be included in a textbook called “The History of Illustration,” I became aflame with the desire to do comix again! I am one third of the way through the completion of my first 36 page new comic book in 40 years, called "Queen of Cosmos Comix." An intricate oil painting for the cover is completed!

M.K. Brown: I just finished an animation project with JJ Sedelmaier for Ford. JJ and I have always wanted to do something together and finally had the chance with this “Distracted Driving” piece. He’s a wonderful person, great to work with. Next, I’ll be photographing paintings and drawings with a new project in mind. After that I’ll finish the Aunt Mary’s Kitchen series and collect all the strips and revise the cookbook I did with Macmillan. I want to put it all together into a useful and entertaining package. (I use the cookbook all the time.) Of course, there are always cartoons in progress, especially now that a lovely new humor magazine has been started called, The American Bystander, edited by Brian McConnachie and Michael Gerber.

Sharon Rudahl: When my kids became older and before China went down the capitalist path, I learned to read Mandarin and I made a lot of friends in China. In the early 20th Century, there was something like the hippie movement in China–the May 5th Movement of 1919. Mao was one of the hangers on, working in a library at this university where everyone was discovering sex and anarchy. There’s a whole literature that came out of that pre-Communist revolution period that’s just amazing. It’s so little known here, but it’s as good as Orwell or Colette. They’re inventing modern language and modern politics. Some of them participated in the fall of the empire and then it became the anti-Japanese movement and out of that came the early communist party. Some of the people I’m talking about lived to suffer in the cultural revolution, some lived through that and got lionized again, and some didn’t live to see what they believed be dragged through the mud. It’s a literature I know really well. I’ve read an awful lot of this stuff in the original and I feel closer to these people probably than anybody now in either country does. This is the one thing I feel I really have to do while I can still do a full length book.

Barbara Mendes: In August of 2015, I completed a 48” square oil painting called “The Book of Daniel.” I do Biblical murals-on-canvas. When I became religious in my late forties, I did one about the book of Genesis (“The Beresheit Mural”); when it sold I did the Book of Exodus (“The Shemot Mural”), which took two years. I begin with ink drawings of every verse, then paint narrative details onto a huge canvas in one color; then color those areas and add brilliant color patterns. “The Shemot Mural” can be seen in at the Sephardic Educational Center the Old City of Jerusalem. The third biblical mural, “The Vayikra Mural,” took three years, and I’m still trying to sell it! Leviticus is a difficult book that nobody likes. [laughs] What I really like to paint is women. I looked into the Book Daniel and it’s nuts. I did study paintings of some of the weird visionary scenes, and made ink drawings of the narrative chapters. I picked a big square canvas and I had a flash about how to organize the painting: in a circle! The painting is a narrative, illuminating everything in the story of the Book of Daniel. You wouldn’t believe my two minute synopsis of the Book of Leviticus. Everyone who visits my gallery has heard it. [laughs] My Los Angeles Gallery is open to the public, and is known for the huge and intricate “Angel Wall” mural I've painted along the length of the building.

Trina Robbins: By the time we finally ended in 1992 there were more women in comics than ever before. We really did open the door for women to do comics. Before the underground there were a few in the mainstream, but it had been a long time since women contributed to comic books as anything other than colorists. Suddenly after the first issue we were getting submissions from everywhere. Because women were reading our book and going, wow, a comic by women. I can do this. I would get fan mail and you have no idea how happy that fan mail used to make me, living alone and being totally shut out by the guys. That’s what Wimmen’s Comix did.

Carol Tyler: I loved that there was a place where you could get published because comics traditionally has been a boy’s game. And you didn’t have to be the greatest draftsman. You could start out there and grow. Now we look back and say, “wow, how precious, our early selves–when we were young and struggling. So proud of this work.” To be able to have that time and place was very good. The politics, the sniping, the jealousies, this is going to happen in the art world, in design, at the office, you name it. But I think it was way worthwhile. It was a grand gesture. It was a great gesture.

Patricia Moodian: A lot of women worked very hard to bring truth to comix. I hope that we encouraged women to love themselves more, to realize they are not alone, and to be stronger as they fight their way through a tough world. I hope that we did some small good in bringing a little more opportunity for women in all areas of the workforce by the example we set with our determination and talents. This anthology carries on the legacy of strong and capable women in comix that Trina Robbins began with It Ain't Me, Babe.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb: I do think historically it’s important. I see several generations of younger women artists– Phoebe Gloeckner, Carol Tyler, Alison Bechdel and other people–who are inspired by our generation. People tell me that they were moved and touched and influenced by my work. That’s one of the most satisfying parts of the whole thing to me. That it turned into an important art form and means of expression for so many people–especially for women–and it didn’t exist before. We created a great form for women artists and there’s some great work out there now.

Roberta Gregory: Wimmen's Comix really inspired me to try to get my own quirky comics and stories out into print, and in front of readers, rather than just creating them for myself over the years. It also demonstrated what a wide variety of art and storytelling styles–not to mention subject matter–could be used in comics. I think it had a huge impact on comics. Howard Cruse mentioned that Wimmen's Comix inspired his editorial approach in 1980 when he was the first editor of the Gay Comix anthology. I know there must be decades of indie comics creators who owe their individualistic creative styles to the ground breakers in Wimmen's Comix.

Jennifer Camper: Wimmin’s Comix created a supportive place for women cartoonists to explore new ways to make comics. The work is still powerful when read today. Many of the cartoonists have gone on to do additional amazing work, and have long careers. Some have never done other comics, but their work is part of our history. Other publications, like Real Girl and Twisted Sisters, were influenced by Wimmin’s Comix. The comics industry has change in many ways, but there will always be under-represented people turning to DIY comics to make their voices heard, and using that as a springboard to infiltrate mainstream culture.

Diane Noomin: In retrospect, I have a higher opinion of the work in the Wimmen's Comix series than I would have thought possible earlier, although my opinion of the “collective” experience has not changed.

Carol Tyler: I think of genuine love and support when I think of Wimmen’s. I think of the enormous talent and beautiful lives of the Wimmen’s contributors. I’m so glad to have been a part of it. So glad it happened. A real treasure.

Leslie Ewing: Frankly, I think the impact is mostly historic at this point. However, I do think artist-driven collaborations have value far beyond the immediate end-product. The processes for collaborations like Wimmen’s Comix were “community-building,” and addressed the very real isolation women cartoonists experienced while presenting humor through a rarely seen gender lens. It is a model that is still being replicated today, although how we collaborate and publish has changed drastically.

Sharon Rudahl: There’s this whole generational thing where people like me are considered useless old fogeys by the younger generation of hip cartoonists. Which is fine! It’s fine to live to be an old fogey. We’re the people who created work that made it possible for today’s hip cartoonists to publish their hip books and get movies made out of them. A lot of the work is really good, and I’m glad–even if I don’t get any thanks. [laughs]

Mary Fleener: The Lofty Goal, as I understood it, for Wimmen’s was–everyone got a chance. The idea was to have a revolving editor, and I support that idea one hundred per cent. I think the worthy legacy is that Wimmen’s was a creative experiment, one that should be repeated. Taking chances, even though it doesn't make a lot of money, is always a good thing. Since comics had been going through a “style revolution”–anything but superheroes–thanks to the undergrounds, many comics were published with drawing styles that were original, flamboyant, crude, unpolished, yet sincere–but utterly unappealing to the comic retailers. So were Weirdo, Rip Off Press, Buzzard, Heck, and many other publications. Wimmen’s Comix will probably go down in history as a significant publication.

Phoebe Gloeckner: There have been many great artists who appeared in the book over the years. Many friendships began there. It was a great place to get to know other people and I guess in a sense the experience was similar to how girls feel at schools for girls. They’re not worried about how the boys are going to think they look. Their minds are free. Being in a collective whose members were all women was liberating. You could talk about and do work about (generally) what ever seemed important or interesting to you. Not everyone would agree with you perhaps, but nevertheless it was a fertile place for conversation and for working.

Lora Fountain: Well, it certainly played a part in the growing underground or alternative comics scene, and some of the women continued as cartoonists, like Trina, Aline Crumb, Diane Noomin, Roberta Gregory, and Shary Flenniken, while others went in other directions, as I did. However, comics still play a fairly big role in my work, as approximately a quarter of the books that I sell are graphic novels–many by younger women cartoonists.

Rebecca Wilson: Last fall I went to the Small Press Expo in Bethesda for the first time and it was thrilling to see what I consider the reincarnation of underground comix. It was a much younger audience and I don’t think they even understand what underground comics were or the history that generated what they’re enjoying now, but I think it’s a direct outgrowth. Look at comics like The Story of My Tits, which I loved. That could not have existed if Wimmen’s Comix had not broken that ground.

Sharon Rudahl: We still hear from students and young women–some young enough to be my granddaughters–who are stumbling on it and being inspired by it in some ways. That defines a legacy about as well as you can define one. It still seems to have some meaning for young people. The graphic novel burst on the scene and comics became an accepted artistic medium–which in a sense to me means it’s on its last legs as far as being an interesting medium. [laughs] Wimmen’s Comix certainly was one of the things that paved the road to that. Underground comics–which then broadened to include women doing underground comics–was a moment in our history that led to some things and ended other things. Its time has past in some ways, but it was incorporated into lots of what is going on now. Would Fun Home exist without Wimmen’s Comix? I don’t think so.

Shary Flenniken: I would say that it was a butterfly flapping its wings influence. I’m sure that it had some effect somewhere along with everything other thing that women did anywhere that was progressive. Things have changed so much for women and every little bit counts. You never know who was affected by something that somebody wrote. The comics world changed, and I think undergrounds affected that. Creators who worked on comics became more important and more well known. That’s huge. I think that the undergrounds had that impact.

Caryn Leschen: There were all different factions that came together in those meetings and not everybody was madly in love with everybody else, but people kept coming to the meetings and doing their comics and editors kept popping up. It created a lot of really good work and a lot of work that is really highly admired now. I hope that the Wimmen’s Comix Compendium does really well and makes us all big stars, but I think it deserves to be honored in a hardback collection and appreciated–like the early Mad Magazine deserves. This stuff is valuable.

Joan Hilty: It’s the personification of the larger legacy of underground women cartoonists. I really think they really contributed a huge amount–especially to memoir and autobiographical confessional comics, that now drives so many literary successful literary graphic novels, webcomics and comics projects. I think that the fact that women creators had a major interest in talking about their lives and to do it in a way that supported other women, which led to how Wimmen’s Comix was created to address that, is a really important legacy.

Lee Marrs: I think the lasting value of Wimmen’s Comix was the longevity and the opportunity that it gave women. Quite a few cartoonists have said, when they saw Wimmen’s Comix it inspired them to do this or do that. Whenever you can contribute to a publication or work of art that can give people inspiration for their own work and to fuel them to do things, that’s of great value.