Invisible Ink

by Bill Griffith

(Fantagraphics Books)

There’s so much here. Bill Griffith’s Invisible Ink is a memoir as fascinating in its way as Fun Home. Where Alison Bechdel gave us a look inside of a closeted life when closets were in flower, Griffith takes us across the border into the times before the times changed, an era that seems terribly remote and yet is so recent you can still hear the echo of the footfalls. It’s a time when conformity was maintained through division of the self. You had a public self who professed and at least appeared to observe all the puritan proprieties and a private self in which all your deviations from the norm were concealed. The public self was like the condom of its day, would categorically declare itself a medical device to be used for prevention of disease only, even as it was surreptitiously the means by which babies were prevented. After a long struggle of integration of public and private, the undivided is like the modern day condom which boldly proclaims, "I'm a birth control device. Deal with it." – even as its prophylactic qualities are more vital than ever. Of course, in the old days the condom was a product purchased exclusively by private selves.

It was a regime of coldness, of the social indifference that operates under the name of self-reliance, and which the Republican Party would have the country return to. According to the myth self-reliance spontaneously generates self-sufficiency, and thereby no one need lift a finger for anyone. In practice it means leaving the hindmost to the devil. Bill Griffith learns late in life that his father had three brothers who were abandoned to their unknown fate and never spoken of. On the maternal side his grandfather's second wife insisted that the clubfooted child of his first marriage be sent away because she wouldn't have a cripple in the house.

Where the paternal side of Bill's family are Wednesday's children born to struggle, the maternal side is bathed in the golden glow cast by an illustrious ancestor. This was William Henry Jackson, Bill's great grandfather and namesake. Jackson was a Civil War veteran and a renowned photographer, first of the American West and then exotic places around the world. His renown imbues his descendants with a confidence and sense of their intrinsic worth.

By the time Bill Griffith comes into the world the tide of postwar affluence has lifted the family to Levittown, and they are inalienably of the middle class. Bill seems to abide on a crossroads of lowbrow culture. His mother is grilled by the FBI in connection with the 1950s quiz show scandals. (Both his father and his mother were contestants on TV game shows, separately, and it is typical of their dynamic as a couple that he washes out and she wins a major prize.) His neighbor Carol Emshwiller is a writer of science fiction and winner of the highest awards that can be got for it. Her husband Ed was to the science fiction magazine cover what William Henry Jackson was to the gelatin silver print, and a pioneer experimental filmmaker to boot. Bill and his father in fact sat as models for one of Emshwiller's covers.

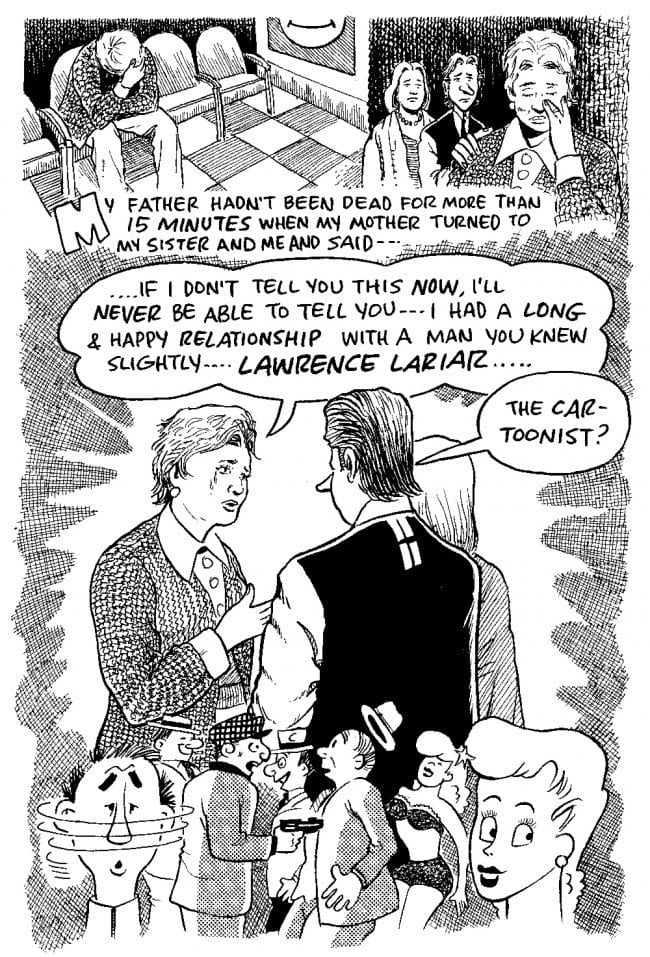

The heart of the story is the 16-year affair the author's mother Barbara Griffith conducted with what the subtitle calls a “famous cartoonist.” The perspicacious reader will suspect that if the cartoonist had actually been famous the jacket would have told you who it was. And yet the cartoonist's very obscurity leads us into an unknown country. We know plenty about the bright bon vivants of the cartoon world, the Peter Arnos, the Charles Addamses, the Edward Goreys, the Al Hirschfelds. We know little of the likes of Lawrence Lariar. Lariar is one of those cartoonists who builds a career not by distinguishing himself but indistinguishing himself. If you are the sort who haunts the humor sections of used bookstores you may have seen his work a number of times and it would not have registered once. Not being capable of delighting or amazing, he has mastered the craft of calculating what will meet the editor's needs at this time, this being the time to fill X number of pages. By its look you will know that it's humorous art. The punchline will be recognizable as a joke, though it will not quite generate the energy for a laugh. It will be suggestive enough to inform you that the subject matter is sexual intercourse but not dirty enough to incite the wrath of the Postal Inspector.

Bill's father James and his secret rival Lariar are in truth curious mirror images of each other. In the inflationary military promotion economy of the World War II and the Korean War, James rises as high in the ranks as captain, and this leads him to believe that Army life is the life for him, war or no war. In the recession in warfare we call peace, however, the Army determines that his natural rank is Sergeant. Feeling scorned and betrayed he resigns, only to find that in the private sector you can be ranked even lower than that. Back to the Army he crawls, discounted for his pains to a lesser breed of Sergeant. Stripped of rank in his career he aspires to be a domestic tyrant, and fails even at that. At least in the Army there are ranks that will not defy him. There is at least the compensation that in the home an officer is allowed to strike a subordinate, notably his daughter.

Like James Griffith, Lariar was frustrated in his career, aspiring to grand things but never achieving them. At the height of his career Lariar manages to grasp the very lowest rung of newspaper syndication, hangs on by his fingertips for a while, then loses his grip. The difference between the two men is Lariar's boundless creative energy and entrepreneurial spirit. With a generic product to sell, he turns his energies to niche markets: cartoon books for golfers, cartoon books for fishermen, cartoon books for bowlers. He is in at the ground floor of comic books, even ahead of Superman, albeit without the pioneer's reward. He is also in at the ground floor also of the paperback boom, writing a number of mystery thrillers yet becoming no Spillane. He casts himself as the star of fumetti-style photo cartoon books. He publishes instructional books, teaching the fledgling cartoonist the ways of marketable mediocrity. His biggest success was a triumph of packaging rather than personal creative endeavor – an annual Best Cartoons of the Year series that ran for years (several years worth of them largely ghost-edited by Barbara and adolescent Bill Griffith). We’ve seen this type cartoon striver before in Seth’s It’s a Great Life if You Don’t Weaken. Where Seth portrayed his subject as a noble and unsung near-miss, Griffith examines Lariar with a combination of hard-headed skepticism and bemused wonder.

It's a Great Life was a detective story. There's no need for investigation in Invisible Ink, because both Barbara Griffith and Lawrence Lariar were demon archivists. It is as if the reporter in Citizen Kane found a note by the bedstead that began, "When I was a boy I had a sled . . ." Like a cartoon Enoch Soames, Lariar donated a meticulously maintained and comprehensive archive of his work to the University of Syracuse, to be discovered by a more enlightened posterity. Like the time-traveling Enoch Soames, Bill Griffith asks the Syracuse librarian how many people have examined it, and is told that he is the first. In the archive Bill discovers things far more intimate than the minute details of Lariar's career when it becomes clear that the sex scenes in his thrillers were likely cribbed from Lariar's afternoons with Barbara.

Where Lariar's archive was created with the intention of preserving an unjustly neglected career, Barbara's archive was a private self's plot to come out of hiding once its confessions could not be used against it in the court of public opinion. Not that the modern day self however integrated broadcasts its marital infidelities to the world, but still these days we are seldom discreet until death. Left among her posthumous effects, for the express purpose of enlightening her children, are letters, diaries, scrap books, and even an unpublished autobiographical novel, recording her secret romance in the most intimate detail. Indeed, all of the Jacksons seem to have been archivists, and Bill's uncle provides him with a box full of photos and mementos to flesh out Barbara's early life. In contrast, at least until Bill came along, the Griffith side of the family preferred to let the dead bury the dead, and black sheep to wander off and never be spoken of again.

The affair begins with a newspaper ad. A cartoonist needs a part-time secretary. This was still the time when men held the keys to every door and women had to bargain with them for access. James Griffith unlocked the door to middle class family life, but the man with the keys can just as easily be a jailer. With the children in their teens, Barbara sees the job as a daytime furlough from domestic duties. James categorically forbids her to take the job. Barbara categorically defies him. Her working relationship with Lariar blossoms into an intimate one. Both Lariar and Barbara are looking for escape, but the escapes they desire are asymmetrical. What Barbara would like is a more companionable marriage, and perhaps a kinder father for her children. What Lariar wants is dessert. His desired escape a woman with whom he can share the pleasant aspects of couplehood – concerts and art galleries and Broadway shows and intimate dinners and bed – and none of the drudgery. Being the one with the keys, he gets to decide the ways of escape they are to take. Whenever Barbara proposes a deepening of the relationship, Lariar changes the subject by proposing another cultural event they might attend.

Lariar's preferred kind of affair is analogous to the suburban way of life itself. The suburb seeks to gather into itself all the things its residents like – home, shopping, school, church – while placing a boundary between themselves and things they find unpleasant – work, traffic, politics, the detritus of industry, the suffering others less fortunate. The missing piece in this puzzle is Lariar's wife. Either because she was no archivist or out of respect for her privacy Bill has nothing to relate about her at all. We might also surmise that the Larial community property was greater than half shares in the Lariar and Griffith assets, even presuming James would have actually paid the alimony.

So, the affair went on, year after year, on Lariar's terms. It must be said that Barbara Griffith distinguished herself more as a philanderer than Lariar ever did as a cartoonist or James as a soldier. To conduct an affair for 16 years with the secret kept and family intact is an achievement in itself. To hang a self-portrait of your paramour over the marital bed while doing so earns you the Nobel Prize in Cuckoldry. James Griffith died with horns like an elk. He might not have deserved them for being a bastard but he earned them by being a bastard.

The end of the affair is precipitated not by discovery but James Griffith's death in a bicycle accident. With half the barrier to remarriage wiped away, Barbara presents Lariar with an ultimatum, and must accept that the answer is dessert or nothing. With keys in hand, she locks the door on Lariar and heads straight into another sad and bad marriage, which Bill lacks the heart to describe in detail.

Throughout Bill Griffith maintains a laudable composure, objectivity and thoroughness. . This leads him away from his strong suit, the sympathetically grotesque, but he deploys everything he's learned about putting factual matter into cartoon form. No doubt he could have taught Lawrence Lariar a thing or two about it. I was most impressed at how he evokes New York City's basket case era with a few background sketches of graffiti-ravaged subway trains.

If the grotesque makes an appearance it's only in the cover illustration. It attempts to depict Barbara winking at the reader, but it looks more like the right side of her face is paralyzed. I have to wonder if this were a spoil that Bill decided communicated something off-kilter about his mother's revelations in a way a more polished job wouldn't. It don't know that it’s been any help in attracting the readership the book deserves. Perhaps it's being mistaken for a Boomer memoir, another artifact of a demographic cohort much of the population would rather not hear about again. If that's what you fear, it's nothing of the kind. It's a "Greatest Generation" story, it’s a Holden Caulfield-era story, it's a New York City story, it's a history of cartooning story, it's a story of a great wide swath of 20th Century American life. It's worthy of your attention.

If the grotesque makes an appearance it's only in the cover illustration. It attempts to depict Barbara winking at the reader, but it looks more like the right side of her face is paralyzed. I have to wonder if this were a spoil that Bill decided communicated something off-kilter about his mother's revelations in a way a more polished job wouldn't. It don't know that it’s been any help in attracting the readership the book deserves. Perhaps it's being mistaken for a Boomer memoir, another artifact of a demographic cohort much of the population would rather not hear about again. If that's what you fear, it's nothing of the kind. It's a "Greatest Generation" story, it’s a Holden Caulfield-era story, it's a New York City story, it's a history of cartooning story, it's a story of a great wide swath of 20th Century American life. It's worthy of your attention.