The new retrospective of Claire Bretécher opened five days after the last Paris attacks. It was a moment when locals were longing to hear from two parts of the populace. One tribe, of course, was philosophers and professional thinkers. But the other group was les dessinateurs – the artists behind popular comics, caricatures and press cartoons.

Bretécher's work helps explain their expectations. She is a virtuoso and a national treasure, an artist whose work explodes with style, wit – and creative complaining. Although both her visuals and storytelling are exceptional, Bretécher's humour exceeds the sum of their parts. She is not someone who depicts "slices of life" nor does she create gags just to end in a burst of laughter. What interests her are the common threads of our existence and what she has to say is always present tense.

Many artists have tried to capture the French cultural psyche but few have made the process funnier than Bretécher. The middle-class comedy of manners she evolved in the '70s was wickedly instant but also prophetic. It nailed a nascent social class while, with issues such as abortion rights and gay adoption, presenting a much larger picture. All of these cultural shifts are catalogued at an intimate level and all are shown from a female point of view.

Technically, Bretécher comments on family, friendship, sex and work. Yet her real interest is in power relations, the ways in which they run our lives and the stereotypes they yield. She zeroes right in on their every hypocrisy, chiefly in the world of well off, Left wing urbanites. There her favorite targets are the self-important, especially the pious promoters of free love and "progressive" lifestyles.

Roland Barthes called Bretécher his country's best sociologist. Other intellectuals, from Umberto Eco to Pierre Bourdieu, were just as flattering. But newer readers don't see her as trapped in this past. Twenty-four year old novelist Clément Bénech (Lève-Toi et charme) reviewed the Bretécher show in Libération. He thinks that Barthes may have missed the point. "A sociologist, maybe. But a sociologist who – with a scaleable and diachronic view of society – always prefers the here and now. She is an artist right at the line of scrimmage."

Yet Bretécher's drawing alone merits Barthes' admiration. Although hyper-expressionistic, it favors observed attitude over stylisation. At a glance, the artist's depictions will seem casual and spontaneous. Yet their every aspect has been systematically planned. The same goes for her dialogue, which broke new ground and set long-lasting trends. (When it comes to the ironies of French "second degree" wordplay, few humorists have managed to profit more.) Visitors to the Pompidou can get the whole story: in addition to over a thousand originals, there are sketches, paintings and ephemera. All of them are further enhanced by televised clips.

Bretécher has never before received a major show. Now 75 and famously discreet, she has little to say about it. But since her contribution to the ninth art is massive, others are more than happy to take up the slack. One of them is Catherine Meurisse, creator of last year's bestseller Moderne Olympia. The artist, 34, also draws Charlie Hebdo's strip La Vie Hormonale ("Life with Hormones"). In style, themes and tone, it is clearly descended from Bretécher. Yet Meurisse was 25 before she saw any work by the artist.

Such involuntary homage, she says, is normal. "So much of what Bretécher did has become subliminal for us. She had a kind of insolence that was all her own, yet it gave us new ways of laughing at our lives and the world."

Bretécher began working early in the '60s. It was a pivotal moment, for her profession but also for France. At the time, comics vehicles such as TinTin and Spirou were still being referred to as "les illustrès". Many of these had begun life before World War II. But talents like Joseph Gillain ("Jijé"), Maurice de Bevere ("Morris"), André Franquin and René Goscinny were re-tooling them. Their changes had transformed the kiddie publications and, soon, they spawned competitors like Pilote and the more adult Hara-Kiri. (Closed down in 1970 for a dig at the death of de Gaulle, Hara-Kiri re-emerged in a week as Charlie Hebdo).

All of these publications were marked by American culture. From the '50s, the draw was post-War US style; come the 70s, it was West Coast counterculture. But, after the tumult of May 68, many Francophones envisioned an "underground" of their own. In the effort to create one, leading roles were played by names such as Cabu, Fred, Siné, Topor, Gébé, Reiser, Wolinksi, Cavanna and Professor Choron (Georges Bernier). Until 1963, however, their ranks were closed to women. That was the year René Goscinny called up Claire Bretécher. He proposed she illustrate Les Aventures du facteur Rhésus, a series he intended for L'Os à Moelle ("Bone Marrow"). This job propelled Bretécher into the heart of a humor renaissance.

Numerous photos and clips in the show take you back to that moment. In every one of these, Bretécher is the only female. (There's an arresting image of her drawing on TV, seated beside Albert Udzero, co-creator of Asterix, Jean-Claude Fournier and the great André Franquin). Whether she is laughing at a party or being interviewed, she remains a slender blonde surrounded by moustaches and ties.

This was a contentious era for the women of France. Only in 1965 could they open bank accounts (before, the say-so of a husband was required). Only two years later was contraception legalized. Homosexuality stopped being a crime in '72, but legal abortions didn't arrive for three more years. This was the world interrupted by riots in May of '68 – one both conservative and complacent about it.

Bretécher herself had spent a dull, Catholic childhood in Nantes. There, the only excitement was her private passion for drawing. At 19, she moved to Paris fully intending to be a painter. "But, here, I discovered that magazines would pay you quickly. There were still publications where you could arrive, hand in your drawings and leave with money." Able to place work at TinTin, Spirou and the Bayard Presse, Bretécher's ideas about her future changed.

Initially she shared the fascination for US comics. Although Bretécher loved the minimal gags of Jean-Jacques Sempé (then visible every week in L'Express), the comic art that most intrigued her was coming out of New York. She adored MAD magazine, Jules Feiffer and the strips by Johnny Hart and Brant Parker.

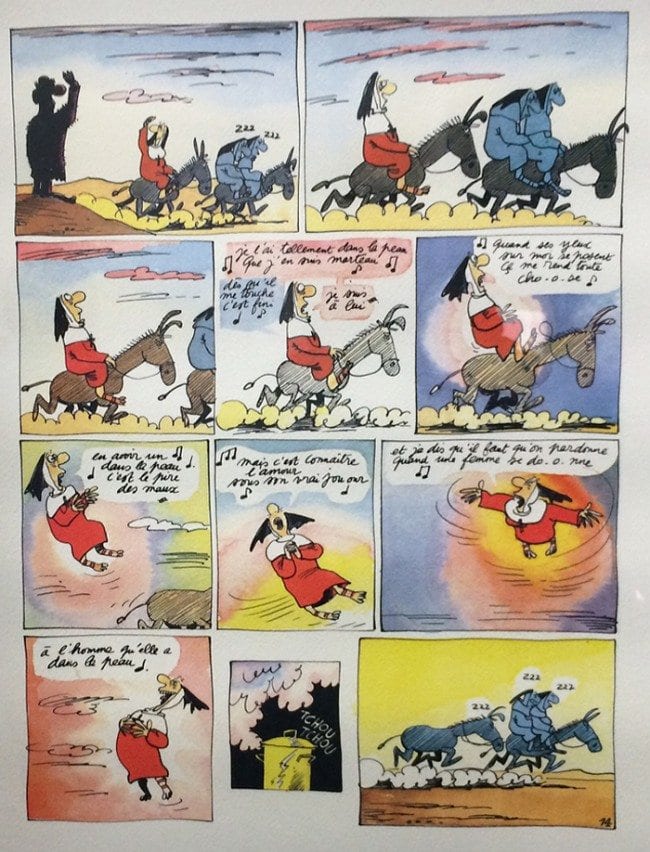

The latter's Wizard of Id inspired her early efforts Robin des Foies, Baratine et Molgaga and Cellulite. All of these series feature medieval kingdoms, dim protagonists and crabby heroines. Deliberately peppered with '60s anachronisms, most of their humour is aimed at social hierarchies. Yet each contains its glimpse of the ligne Claire to come, with its amazingly concise distillations of character. Critics soon became aware that, as Kim Thompson once wrote, "Bretécher's bizarre faces can convey any feeling or any mixture of feelings".

During her formative years, Bretécher free-lanced tirelessly. She worked at TinTin in '65 and '66, for Spirou in '68 and, starting in '69, for Goscinny at Pilote. Although determined to live by her art alone, she found it difficult. "Today that period gets held up as a golden age. But it was really atrocious, always moving from squat to squat."

As for the initial break Goscinny had given her, that too went less smoothly than the legend. "Back then I couldn't really draw the way he wanted. So he finally told me I would have to quit. To stop and come back when I acquired a few more skills." Later, the artist discovered that Goscinny also found her dirty. ("He had a thing about neatness and, living like that, I probably was a little bit grubby.")

By the mid-'70s Bretécher was a star, one on familiar terms with her most famous colleagues. After the tumult of '68, many of them were feeling trapped. Although their employers aimed to keep the mainstream happy, they were bursting with dissident (and X-rated) aims. One night in '72, Bretécher found her pal Nikita Mandryka on her doorstep. Goscinny had just rejected an episode of his Pilote series and the artist was livid. He had, he said, totally lost patience with their mutual editor. "Nikita told me he and Marcel (Gotlib) intended to start a magazine. Gotlib wanted to draw cocks and Nikita had things to prove. I had no reason to join in, but it sounded like fun."

The result was a quarterly called L'Echo des savanes (loosely, "Posts from the Prairie"). During the eleven issues Bretécher helped to create, the trio of celebrities wrote and drew everything in it. Just like Hara-Kiri and Charlie mensuel, L'Echo was daring, dark and often pornographic. Its debut cover read "Réservé aux adultes".

For the French bande dessinée, it marked a historic turning point. The first "adult" album, Barbarella, had arrived back in '64 – but it was promptly censored. It took almost a decade, but L'Echo clinched the fact that a Francophone "underground" had become reality. Drawing on satirical habits that went back centuries, it carried forward the spirit of Hara-Kiri. Which is to say it was narcissistic and anarchic – and "adult", in that married the sexual, the scatological and the political. With the exception of its photo-comics, however, little about it would have surprised Voltaire. But L'Echo's initiative encouraged other pioneers. Métal hurlant appeared a year later, followed in '75 by Fluide glacial.

Brétecher's unique standing has less to do with "first woman" status than with what her contributions meant for that moment. Two things distinguished her presence on the page: a total independence and a personal audacity. In autumn of '73, she startled all her colleagues by leaving L'Echo for Le Nouvel Observateur. This was a Left-wing socio-political weekly, but it was one that had managed to gain a general audience. Commissioned by its editor to make fun of the paper's milieu, Brétecher launched her legendary strip Les Frustrés ("The Frustrated").

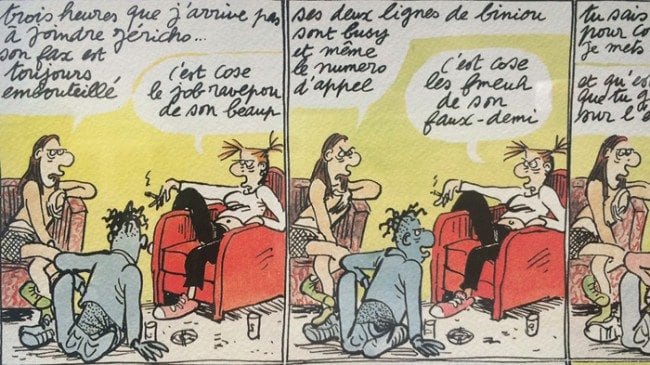

The Nouvel Obs was already publishing cartoons by Copi (Raúl Botana). But Brétecher's series changed comics' role in the journal. Right away, Les Frustrés was popular and influential – and it did much more than just make fun of its readers. The weekly page took aim at an emerging social class, those metropolitans who are now known as les bobos or "bourgeois Bohemians". Many of them, just like Brétecher, had endured a conservative childhood. Yet all had escaped the real traumas of War and want. What her series most relished, though, was the central contradiction of their lifestyle. On the one hand, these are people who can't resist their era's new consumer bounty. On the other, they still claim the Left-wing values of May '68.

The group Brétecher satirised remains little changed today. They are still le gauche caviar, the "champagne socialists", who dominate so much about Parisian life and image. From the very start, however, her portrait of them was totally pitiless. Although easily recognized, the characters are hardly loveable. Clearly, they are suckers who fall for every modish fad and who are in love with the sound of their own voices.

The artist's view of their consumerism has proved eerily prescient. One strip, for instance, features a Dad who scolds his daughter for reading TinTin au Pays de Soviets. (The book was then frowned upon because of its anti-Communism.) Yet once Dad recalls the vintage album's worth, he stops abruptly – impelled to determine if it is real or merely a reprint. In the age of eBay, the snapshot remains just as more telling.

Les Frustrés marked a new beginning for the artist. As she told writer Marie-Ange Guillaume, "For a long time, I had been struggling to find my style. You know what you want but you don't quite know how to get it. So you end up copying – everything from left to right. One day, I simply had it. Finding your trait is like finding your handwriting."

The pages on display at the show are marvels of graphic ingenuity and they all reveal Bretécher's genius for composition. Sometimes a strip will have no text outside of its title. But, where there is dialogue, the artist hand-letters every scrap. (She also pays close attention to its shape and weight on the page). Brétecher often does away with speech bubbles entirely and, if this confuses who is speaking, that's okay. After all, characters like those of Les Frustrés are interchangeable. All belong to the same milieu, what one critic has called "conformists of anti-conformity".

Brétecher begins her work with pencil sketches on tracing paper. When she is finally happy, she inks a penultimate version on top of the softer graphite. In this manner, frame by frame, she finalises all her kinetics. At last, the tracing paper is placed on top of a light box where, using paper and ink, Brétecher replicates the backlit artwork. Anything she doesn't like is scraped away with a razor blade and the completed work is made fast with a hair-dryer.

But you don't need these details to savor the show. All by itself, Bretécher's drawing is enough. The vibrant integrity of her draughtsmanship is stunning and it re-envisions the graphics of body language. This is someone who can seize upon a single gesture, freeze it and extrapolate an entire character from it. Or keep a figure immobile for frame after frame, until a single movement reveals the whole persona. With bodies that are both contorted and marshmallow-soft, Bretécher conveys complete (and complex) emotional states.

Aude Picault, 36, is the author of L'air du rien, another contemporary chronicle in the Bretécher style. She has long been a keen admirer. "As an artist, Bretécher stayed outside the comic codes. Yet her work's mechanics – and its rhythm – are prodigious. She's like a great film director who reconciles us to our small sadnesses, our awkwardness and our private fears we are ugly."

Brétecher also gave the world some unexpected characters. In addition to Les Frustrés, there is her ecstatic saint from La Vie passionnée de Thérèse d'Avila. There are 1982's Les Mères ("The Mothers"). These are not actually mothers, but mothers-to-be and wishful thinkers. Their self-involved view of maternity shocked many initial readers, as did the fact that some among them are gay. (The twelve-page narrative Bernard et René features male lovers who kidnap "their" child as well as an "ideal man" who turns out to be female).

Then, in 1983, Bretécher went further – with Le Destin de Monique. A slapstick farce about IVF, Monique appeared along with the first French "test tube baby". The album's central character is an actress called "Brigitte Sevruga". Sevruga has to have it all: a baby, a perfect figure and a packed filming schedule. But her search for surrogate motherhood triggers an avalanche of disasters. The campy plot intertwines the lives of actors and immigrants with those at a Paris medical clinic and on a rural farm. Along the way, it touches on medical fraud, incest and bestiality.

Bretécher's best-loved character, however, is the teenager "Agrippine". Unsympathetic and irresponsible, Agrippine changed how adolescence was represented. Over eight albums, she also confirmed her creator's uncanny ear for teenage speech. (As usual for Bretécher, the dialogue is equal parts observation and invention). Today, echoes of Agrippine are seen throughout Francophone comics – from girly blogs online to strips like Riad Sattouf's Le Vie secrète de jeunes ("Secret Lives of the Young") and Les Cahiers d'Esther ("Esther's Diary").

Briefly, late in the '70s, Bretécher made it into English. But the reasons, like the translations, are debatable. Both Ms and Viva published pieces of her work and the National Lampoon even bought out an album. But this all involved a view of the artist as proto-feminist, something she herself has always denied. The world Bretécher entered, as she says, was never all-male for long. It was soon being shaped by plenty of women – like Nicole Claveloux, Chantal Montellier, Florence Cestac and Jeanne Puchol.

Beginning with Les Frustrés in 1975, Bretécher decided to self-publish all her albums. For over three decades, she did so. The publishing house Dargaud now holds control of her work. Bit by bit, they are re-issuing all of it, including a complete set of Les Frustrés. But that early independence, on top of her personal reticence, ended up somewhat obscuring Brétecher's place in history. The comics specialist Fabienne Dumont calls it a scandal. "I'm teaching BD history every day, so I need to cite her work all the time. Yet, again and again, I find my students have never heard of her".

Last autumn, female cartoonists united to found the Collectif des Créatrices de la bande dessinée contre le sexisme. Hardly was it announced before artists were flocking to join. From best-selling names like Margaret Abouet to less conventional creators such as Tankxxx, every member is happy to be labelled a feminist. Joined by their colleagues from elsewhere in Europe (as well as Britain, America and Canada), these two hundred women want to make a simple point: Whatever the sex of an artist, comics are comics, art is art…and talent is talent.

Claire Brétecher didn't join. But, over five decades, that has been her mantra.

Her retrospective occupies the gallery inside the Centre Pompidou's library – one of the biggest and busiest student hangouts in Paris. This has helped it conquer a new, digital generation. But the show has re-awakened many Parisians to the skill with which Brétecher sees them. Although these locals come to see themselves get skewered, what they take away is something more sustaining.

Charlie Hebdo's Catherine Meurisse certainly understands. After the attacks, almost spontaneously, she says she turned toward Bretécher. Of course the older artist had worked with many of those who died. But that wasn't what drew Meurisse was back to her work. "In our generation, you just don't find her kind of depth and development. She remains a monument, totally unique."

"In all her work there is also an absence of seduction. With Facebook and all that, we're now immersed in seduction and narcissism. Bretécher understood seduction perfectly well. But she just said 'Merde!'. She knew nothing is ever lost by standing apart, not trying to please. That, to me, seems an excellent model for today."

Claire Bretécher, at the Centre Georges Pompidou Bpi, runs through 8 February 2016 and entrance is free. Le Collectif des Créatrices de la bande dessinée contre le sexisme is at http://bdegalite.org