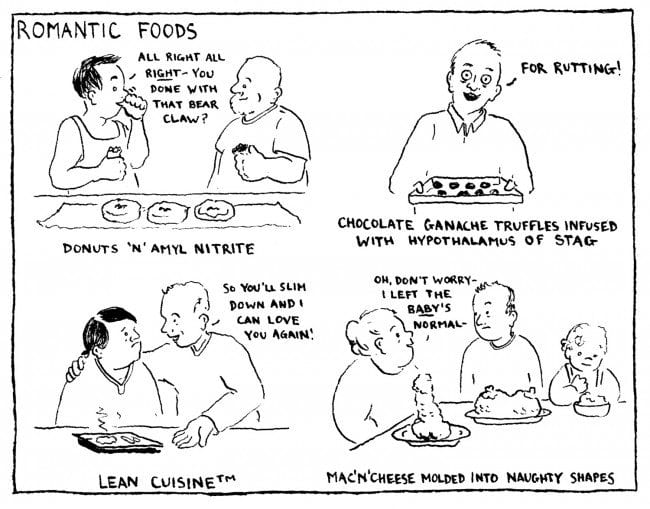

Emily Flake is the mischievous artistic child of Roz Chast and Shary Flenniken – with some Edward Gorey and Gahan Wilson thrown in. Like Chast, she nails the middle-class annoyances and vanities of everyday life in the big city while, like Flenniken, blending "the cute and the profane." The Gorey and Wilson you'll just have to discover yourself in the more mordant nooks and crannies of her cartoon persona.

Flake, who has been publishing her syndicated Lulu Eightball strip since 2002, started drawing for The New Yorker in 2008. Her debut for the magazine is a dark pass-agg classic in which a disapproving father says to his daughter, “I’m not disappointed – I’m just very, very mad." In Flake's world (she lives in Brooklyn, natch), adults essentially are children: frequently drunk children, but children nevertheless. In a gentler, subtler way, the aforementioned drawing's pained interaction between parent and child informs her new book, Mama Tried: Dispatches From the Seamy Underbelly of Modern Parenting (Grand Central). The alcohol-nourished ghost of Dorothy Parker hovers over so much of Flake's work that you almost begin to worry about her liver. She claims parenting has tempered her thirst, but her work is all about embracing one's flaws and appetites with gusto. But like all great comedy liberationists, including Parker, she's a moralist at heart. And anyone who can combine boozing and parenting with the economy of a line like that of a wine-imbibing parent who says to her child, "It's a magic potion that makes everything you say interesting," is a mother of a humorist indeed.

The alcohol-nourished ghost of Dorothy Parker hovers over so much of Flake's work that you almost begin to worry about her liver. She claims parenting has tempered her thirst, but her work is all about embracing one's flaws and appetites with gusto. But like all great comedy liberationists, including Parker, she's a moralist at heart. And anyone who can combine boozing and parenting with the economy of a line like that of a wine-imbibing parent who says to her child, "It's a magic potion that makes everything you say interesting," is a mother of a humorist indeed.

RICHARD GEHR: When did decide to take the plunge and submit to The New Yorker?

EMILY FLAKE: In 2007 my friend Emily Gordon, who was the editor of Print magazine, introduced me to her friend Drew Dernavich, and he was like, “If you ever want to submit, let me know and I’ll go in with you so you don’t feel all scared and alone.” I think The New Yorker is at least in the back of the mind of anybody who does cartoons. I had no idea how the process worked. I didn’t know it was this thing where you just went and had a sit-down with [cartoon editor] Bob [Mankoff]. I thought they either reached out to you or The New Yorker fairy showed up on your doorstep. [Laughs.] But I went in with Drew and started submitting every week. I want to say I submitted for seven or eight months before they bought one, which seems plausible – although now I’m wondering if I started submitting in 2006, because I feel like I took the week of my twenty-ninth birthday off and I remember feeling bad about not submitting that week. I don’t know. I’m way overthinking this! Sometime roughly eight or ten years ago…

GEHR: What was the first drawing you sold?

FLAKE: It was a father looking disapprovingly at his daughter and saying, “I’m not disappointed – I’m just very, very mad.” It was a pretty boring trajectory after that: I kept submitting and they kept buying stuff and after a couple of years they put me on a contract. Which is nice, ‘cause it’s more money.

GEHR: The contracts usually stipulate that The New Yorker gets the first look at anything you draw for publication. Do you have to show them your syndicated Lulu Eightball stuff before you send it off?

FLAKE: No, I get special dispensation for Lulu. And calling Lulu “syndicated” is a perversion of the word since it’s only in about three alt weeklies now. So because it was something I was already doing when I first started submitting to The New Yorker, and because about four people read the strip, I think Mankoff was like, “Go ahead and do your adorable little comic strip on the side.” It’s actually written into my contract that I don’t have to show him Lulu ideas. Though because I’m very lazy, I will often sort of write a Lulu, submit it, and if it doesn’t sell I’ll Lulu it up and use it for the strip. So, yeah, you know, efficiency.

FLAKE: No, I get special dispensation for Lulu. And calling Lulu “syndicated” is a perversion of the word since it’s only in about three alt weeklies now. So because it was something I was already doing when I first started submitting to The New Yorker, and because about four people read the strip, I think Mankoff was like, “Go ahead and do your adorable little comic strip on the side.” It’s actually written into my contract that I don’t have to show him Lulu ideas. Though because I’m very lazy, I will often sort of write a Lulu, submit it, and if it doesn’t sell I’ll Lulu it up and use it for the strip. So, yeah, you know, efficiency.

GEHR: Where else do you publish?

FLAKE: Mad Magazine still buys gags. A lot of New Yorker rejects go there. Sometimes I sell to Hilary Price, who does “Rhymes With Orange,” which is basically a strip format but often a single-panel thing. I hope it’s not a secret, but I’ll send it to her and she draws it, obviously. And Canada’s premier humor magazine, Canadian Business, was a pretty good repository for a while. [Laughs.] But they stopped running cartoons a while back, which was too bad ‘cause they paid well. There are so few outlets for gag cartoons. It’s pretty much down to The New Yorker and a handful of other places that don’t pay nearly as well.

GEHR: What’s your back-story? Where did you grow up?

FLAKE: I grew up two towns east of Hartford, Connecticut, in a place called Manchester that defies description in its dullness. It was the suburb of a very sad, small city. I left there when I was seventeen and went to the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. Then I lived in Chicago for four years and moved to New York eleven years ago. I’ve lived in cities my entire adult life, and have every intention of doing so until…

GEHR: What’s your birthday, for all the astrologers reading this?

FLAKE: June 16, 1977.

GEHR: What did your parents do for a living?

FLAKE: My father worked for Travelers Insurance. I think he started out as an actuary and then did things which are obscure to me – ‘cause who the fuck knows what their dad does when he puts on a suit and leaves the house? My mom had various secretarial jobs here and there, none of which lasted particularly long. It was pretty basic middle-class, white-collar life.

GEHR: Did they subscribe to The New Yorker?

FLAKE: They did not. They subscribed to Newsweek and the local newspaper. But when I was five, my dad went to the library and brought home books by Gahan Wilson and Edward Gorey. And I very distinctly remember looking at them and being like, “This is what I want to do with my life!” So that was the first step on my journey to stardom! [Laughs.]

GEHR: And hence the dark undercurrent in your work.

FLAKE: Yeah, right. It’s a very chicken/egg kind of thing. Did that give me the undercurrent or did I respond to it because it was already there? But I was, and am, a huge fan of both cartoonists.

GEHR: Were you one of those kids who drew constantly?

FLAKE: Yeah, I drew quite a bit. I feel like I had a lot invested emotionally in being the best drawer. So it really bothered me when some other kid was good at it. Like Becky Smith was really good at shading, and it bummed me out. [Laughter.]

GEHR: So I guess you had to really step up your inking skills.

FLAKE: I had to kill her and bury her in a shallow grave.

GEHR: Do have any specific Wilson or Gorey cartoons tattooed on your cerebral cortex?

FLAKE: I forget the gag line, but there’s one Gorey cartoon about a big bug that terrorizes this peaceful community of little multicolored bugs. That one’s burned in my brain because I still love the dark color scheme with these little primary-colored bugs. And The Gashlycrumb Tinies, of course and the whole sort of…obviously I would not have said “David Lynchian spaces” when I was five.

GEHR: Probably not.

FLAKE: Not till I was like ten. Gorey’s airless, gloomy, subconscious nightmare spaces were very fascinating to me. With Gahan Wilson, I remember really liking all the toys in the attic saying, “One of these days he’s going to come up here all nostalgic…and then we’ll get him!” But that’s a really famous one, so now I don’t remember if I actually really liked that one or if I’m interpolating that into my childhood memories.

GEHR: What’s the first New Yorker cartoon you remember blowing you away?

FLAKE: That’s a really good question. Probably, like everybody else, it was by Roz Chast, because I’ve loved her work ever since I started noticing it. I don’t have a specific gag I remember looking at and being like, “Oh my god, this is amazing!” I didn’t really start looking at The New Yorker until I was in college, and even then it was probably in the bathrooms of my smarter friends. So it wasn’t like a touchstone growing up or anything like that.

GEHR: The Maryland Institute College of Art seemed like a happening place when I was at Johns Hopkins for a year.

FLAKE: I may have delivered you a pizza.

GEHR: What was that great bar everyone hung out at?

FLAKE: The Royal Tavern. Yeah! Gin and tonics were two dollars and ten cents. [Laughter.] It was a good place to drink yourself to death.

GEHR: Was anyone teaching cartooning when you were there?

FLAKE: Not really.

GEHR: Was cartooning ghettoized?

FLAKE: When I got there it was all VisCom, just Visual Communications: graphic design and illustration. Then they split them into separate departments. But comics as such had not quite gotten to the point where people felt it deserved a lot of attention, and MICA at that time was a super-heavy painting school. I think they’ve since shifted focus to try to be more of a leader in terms of graphic design and things one could hope to make money doing, because it is now ungodly expensive. At that time even the graphic-design people felt a little looked down upon because they weren’t painters. That being said, the illustration department had some amazing instructors and, ironically, it was a painting teacher who sort of validated what I was doing with comics. Ken Tisa was a fantastic instructor and a great guy. I started doing these funny little things and he was like, “This is amazing! Keep doing this!” I knew I wanted to be an illustrator, and the idea that I could combine humor and illustration began to gel in my head. When I was in high school, I had a fanzine and I made little comics for that.

GEHR: What was your zine called?

FLAKE: Puddle Jumper Weather Stomper. I don’t know why. I just liked doing layouts and writing little stories and doing comics. I loved making that thing.

GEHR: Have any lying around?

FLAKE: Sure! I really got into making things via photocopying, cutting, and pasting. When they tried to teach us how to do that on computers, I was like, “Aaargh! That’s hard! That’s boring!” In retrospect, why did I not just be like, “This will make things ten thousand times easier”? But I’m still pretty lousy. In the computer programs of my chosen craft I am no expert.

GEHR: Sometimes you’ve just got to keep it real.

FLAKE: I’m conversant enough with Photoshop but I’m a disaster in Illustrator. Kinda the same deal with InDesign. It’s funny: I always have this moment of panic when I don’t know what to do. I need to start listening to the voice that’s like, just shut up and learn how to do it. It is literally not rocket science. [Laughs.]

GEHR: What happened after art school?

FLAKE: I moved to Chicago in 1999, basically because everybody else did. At the time I think everyone was like, “We can’t possibly ever afford New York.” If my core group of friends had stayed in Baltimore, I would have too.

GEHR: Baltimore’s a screwed-up yet fascinating place.

FLAKE: I love that city with all my heart, I really do. But I also had older friends who’d been there a while and had started to hate it – and I did not want to reach that point. Unlike New York at that point, Chicago seemed like a place I could wrap my head around. Chicago was more expensive than Baltimore, but I could hope to afford it. I was there four and a half years. I was a waitress and I worked for a record distributor called Carrot Top. I’m a great warehouse worker. That’s another thing I can do. And I was ostensibly in sales for Caroline Records. I never really felt at home in Chicago, which makes me feel a little sad because it was a great place. I still have a lot of really wonderful friends there, but my heart was never quite in it. I don’t know if that’s a result of having grown up on the East Coast. This seems silly to say, but the weather is really bad, truly awful. Chicago is the perfect city on paper, but I just never fell in love with it. I am not so good at what I do that people are going to find me. I was like, if I’m going to make a go of this I have to move to where things are happening.

GEHR: New York’s our company town.

FLAKE: Exactly. So I moved here with like $110 dollars in my bank account.

GEHR: Brave! [Laughter.]

FLAKE: Brave is one word for it! But it worked out, knock wood. I had a car when I moved here. I was living with friends of friends, and I heard this crunch as I pulled up to their house. I had run over a little plastic smiley face and I was like, “What does it mean?!”

GEHR: Sort of like Watchmen.

FLAKE: Yeah. It was January 2004. I shipped most of my stuff through work from Chicago and packed my car as tightly as humanly possible.

GEHR: Did you have New Yorker aspirations at that point?

FLAKE: My focus was not on single-panel cartooning at that point. Lulu Eightball started in 2002, so I’d been doing the strip for a while. But I was more focused on illustration at that point. I really, really wanted to make it as an illustrator, even though I had cartooning in the back of my mind. When I first moved here, I started doing these sort of humorous PowerPoint presentations for these comedy nights. In retrospect, I feel like I should have realized that that was a bigger deal than I thought it was, and focused a little more on that. But I was like, “Maybe I’ll get some illustration gigs out of this.”

GEHR: I didn’t know you were a performer.

FLAKE: Yeah, I did some nights at Rififi and a couple of other comic venues. But I just saw that as a means to more illustration stuff. What a dummy!

GEHR: What were those gigs like?

FLAKE: Basically I would just make comics and present them. You’ve been to Carousel, right?

GEHR: I’m embarrassed to admit I have not.

FLAKE: It’s just people reading and performing comics and trying to interject witty asides. My technical know-how was minimal when I first started doing it, so I’d be like, “I hope you have a computer.” I remember showing up once and they didn’t have the equipment. It didn’t occur to me that it was my responsibility to make sure the thing I’m doing can happen. So I showed up and they didn’t have a set-up, so I was like, “I’m going to go print this out and photocopy it and people can just read along.” Which is a thing that I did. In retrospect, I should have been paying more attention.

GEHR: So you’d just bring in your own work, show it, and riff on it?

FLAKE: I would make like twenty-panel stories and just click through it, panel by panel. And that’s a thing I still do every now and again. It was fun. One night somebody from Mad was there and said, “I’m going to send you a submission packet. Send some stuff in.” That was pretty awesome.

GEHR: What were your stories about?

FLAKE: The first one I did was before I even moved here, in September 2003. It was for a night John Hodgman did called “Little Gray Books.” I don’t remember what he told me I was supposed to do, but I had one of those little brain-teaser puzzles, and so I did a made-up comic history of this puzzle. It hadn’t occurred to me that I could do this, or that it was a thing people did in general. So if it was around New Year’s I’d have predictions for the coming year. Or I’d tell funny personal stories through comics.

GEHR: Where else did you perform?

FLAKE: I did some stuff at the Magnet Theater. I did a thing at City Winery not too long ago. The Lolita Bar had a great long-running night called “Tell Your Friends,” and I did a few of those. Whoever will have me, basically. [Laughs.] The free-lancer’s motto.

GEHR: So true. Never say no!

FLAKE: Exactly. I can count on my hands the times I’ve said no to an assignment or invitation.

GEHR: Do you have a “process,” as they say?

FLAKE: [Laughs.] Well, first I put on my cartooning gown…

GEHR: I bet it’s a doozy.

FLAKE: I wish I had a better answer for that than just sitting down to stare at a blank piece of paper, and crying until an idea comes. But that’s pretty much the process. I write first, so I just start writing stuff down and try to free-associate. I keep an eye out for funny things during the week. I have a running ideas note on my phone.

GEHR: What’s your weekly schedule?

FLAKE: Well, the cartooning meeting is Tuesday so, you know, Monday. [Laughter.] When I’m being my best self, I spend a few hours every day on it. But it always just runs into like, “Oh shit. Gotta do it, gotta do it, gotta do it! So again, I really wish I had a better answer for that.

GEHR: What are the tools of your trade?

FLAKE: I use pencil on typing paper for the roughs and then for the finals I am partial to Arches 140-pound hot press paper. I use dip pens and acrylic ink, which a lot of people hate, but I love acrylic ink. Every once in a while Microns, but not too often.

GEHR: The New Yorker didn’t seem to have had a new female cartoonist on contract for quite a while until you came along.

FLAKE: They’re working on it. More women are submitting now, which is great. They’re reaching out to both women and people of color, which is an even more glaring omission – both in the drawings and in the people making the drawings. Bob [Mankoff] actually got together with SVA [School of Visual Arts] to start a cartooning class there in hopes of bringing in younger and more diverse voices. And I am actually teaching that continuing-education class. The plan is to eventually offer it to undergrads in hopes of attracting even younger and more diverse artists.

FLAKE: They’re working on it. More women are submitting now, which is great. They’re reaching out to both women and people of color, which is an even more glaring omission – both in the drawings and in the people making the drawings. Bob [Mankoff] actually got together with SVA [School of Visual Arts] to start a cartooning class there in hopes of bringing in younger and more diverse voices. And I am actually teaching that continuing-education class. The plan is to eventually offer it to undergrads in hopes of attracting even younger and more diverse artists.

GEHR: The New Yorker’s not exactly known for its diversity, but that appears to be changing, thankfully.

FLAKE: Absolutely. It’s tricky, because as a cultural magazine it both reflects and guides the culture. It’s more reflective of the culture at large, but I feel the cartoons are a little behind that curve. But they’re trying to catch up.

GEHR: There’ve been a few provocative articles and Facebook posts lately about, for example, black male writers pandering to white middle-class suburban female readers, who buy most of the books these days, or white female writers pandering to white male readers. Which leads me to ask, perhaps foolishly, whom do you pander to?

FLAKE: Who am I not pandering to? I feel like that’s possibly less of an issue with cartooning. Am I pandering to anybody? I don’t feel like I am. Certainly with the Lulu stuff I can do whatever the fuck I want, because I get paid nothing. Which I feel bad saying.

GEHR: The stakes aren’t there.

FLAKE: Yes. It’s great because I get to do whatever I want in Lulu. It’s obviously different with The New Yorker. I submit things with an eye toward its editorial voice. Whether or not that counts as pandering to an establishment is open for debate, I guess. I think it also helps that I’m not particularly far outside of its demographic, both in terms of editorial voice and readership. I mean, I’m a middle-class white person who went to college.

GEHR: From Connecticut, even.

FLAKE: East of the river, though! I feel like that bears mentioning.

GEHR: Noted. [Laughter.]

FLAKE: I don’t feel like I’ve spent years in the trenches trying to apply whatever gifts I have in the service of somebody whom I feel less than, if that makes sense. I don’t feel like I’m laboring under a yoke of pandering. Even as a writer, and certainly in Mama Tried, I felt like I had an open mic in terms of what I was able to say.

GEHR: Do you get many editorial notes from The New Yorker?

FLAKE: I get notes every once in awhile. I am often told to make my people less fat.

GEHR: Interesting. I wonder if, say, Zach Kanin gets those.

FLAKE: I wonder if he does too! I think the justification there is whether or not the drawing is about a fat person. You might also ask whether or not a certain cartoon is about the people in it being non-white. I think sometimes a person in a cartoon can just be fat, or a woman, or black, or whatever! That might speak a little to the pandering question. Simply assuming that the cartoon norm is a thin, affluent white person is a structure that I think deserves to be questioned and altered when and where it can be.

GEHR: Which leads to the question of whether or not we’re living in hypersensitive times, too.

FLAKE: In some ways, yeah. But in other ways I feel like we have to be a little hypersensitive. I do a lot of eye rolling at things. But forty years ago I might have been eye rolling at things that have directly benefited me as a woman.

GEHR: Such as?

FLAKE: Like the whole feminist movement of the sixties and seventies. So I feel like I have to watch myself if I’m looking at kids on campus agitating for something. Because my knee-jerk reaction is like, “Oh, you fucking babies! Get it together!” You know? But as someone who has directly benefited from cultural agitation, it’s a little more my duty to be like, alright, what are they upset about? I don’t like reactions that limit speech. I find trigger warnings and the like infantilizing, and I think they have a chilling effect on speech and expression, etcetera. There should always be room for people to vigorously disagree. But I am totally OK with buildings not being named after Woodrow Wilson anymore.

GEHR: Let’s talk about rejection. Does it break your heart when a favorite drawing is rejected?

FLAKE: Yeah, but you can resubmit those. There are some I’ll resubmit until they take it. Others are fairly innocuous, and I’m not sure why they weren’t bought. And with some I’m like, “OK, I know why you don’t want that.”

GEHR: What’s an example of a drawing you had to resubmit multiple times?

FLAKE: I know there are a couple I put through a few times before they took them. I’d have to look at my Cartoon Bank page. There’s one I’m still fond of they will never take, because it’s Jesus on the cross, and he’s saying to the person nailing him up, “Carpenter to carpenter, you’re gonna want to use a stronger nail.” [Laughter.] Jesus’s utility as a carpenter is not often addressed. What if he was a really shitty carpenter? We don’t know!

GEHR: He didn’t appear to work a lot.

FLAKE: Exactly! He seems to have spent a lot of time yapping.

GEHR: Maybe he had a no-show union job.

FLAKE: There’s another one I’ve submitted a bunch of times they’ve never taken. Maybe they’ve had something similar in the past. It’s a middle-aged couple at a restaurant. They’re peering at the menu and the waiter is holding a plate of reading glasses like, “Would madam and sir like some?” That’s both funny and relevant to all of us in our thirties and forties who are rapidly losing our eyesight

GEHR: How did you arrive at the four-square format you use for Lulu Eightball? Isn’t that four times as hard as drawing a single gag?

FLAKE: I hit on that fairly early in the process, and I remember feeling almost like I was cheating by using more words than I was allowed. Like, “They only gave me one panel and I’m trying to make it four and they’re going to get mad at me!” I fell into that and just really liked the rhythm of it. Roz Chast is definitely one of the progenitors of that style. I don’t recall if I was consciously influenced by her stuff or not. But that rhythm suited me, and the way I write jokes, very well.

GEHR: Did you use that format from the beginning?

FLAKE: There were a few single panels in the beginning. But I fell into the four-square rhythm pretty quickly. One of the reasons I enjoy it so much is because it’s a different way of thinking than a single-panel gag. In some ways it’s easier. I’m basically just making lists. The structure’s already there, so it doesn’t even have to be well though-out in a quick in-and-out kind of way. I’m glad I still get to work in both formats. The New Yorker has bought a couple of three- and four-panel things from me, so that’s nice. Also, the Lulus are very small, and I’ve always drawn them very small, which is ridiculous. When I started, I wanted to draw them the size they would run so that I would know how they were going to look. In retrospect, I should have drawn them bigger so they’d look better and I’d have more room. I draw these tiny little chicken-scratch things and sometimes I’m just like, “That looks terrible!” It gives them a sort of doodle-ish thing I hope is successful.

GEHR: How did you approach Mama Tried differently than you did These Things Ain’t Gonna Smoke Themselves? Did you know there’d be a lot more writing involved with Mama Tried?

FLAKE: These Things Ain’t Gonna Smoke Themselves was more or less an illustrated essay. It was much smaller physically and the rhythm was much more like drawing-with-sentence, drawing-with-sentence, drawing-with-sentence. It was a very different thing.

GEHR: How did Mama Tried come together?

FLAKE: Tim Kreider’s agent, Meg Thompson, helped me bang my idea into better shape, and then she sent it out. It wasn’t anything close to a finished book, and in fact it was sort of conceived as mostly straight cartoons. But then Ben Greenberg, my editor, was like, “How would you feel about it being sort of half-writing, half-cartoons?” And I was like, “Sure! That sounds like less work.”

GEHR: Have you done much writing before?

FLAKE: Yeah, essays and very light journalism. It’s always been part of my wheelhouse, so to speak.

GEHR: There are a lot of parenting books out there. Was that a consideration?

GEHR: There are a lot of parenting books out there. Was that a consideration?

FLAKE: Yeah, there’s a huge glut of parenting books. There are definitely some humorous parenting books, but it’s possibly not as overloaded as the parenting-manual niche. There’s a certain amount of parenting memoirs, but not a lot of comic parenting memoirs. And there aren’t a lot of graphic books about parenting. One I loved was Let’s Panic About Babies!, which wasn’t comics per se but was definitely a humorous take on the formation and delivering of babies. Since a lot of what I do in terms of material is drawn from life, this was obviously a big life event I could use. Basically, I just wanted to monetize having a child as much as possible. [Laughter.] That was important to me.

GEHR: You definitely have a feel for adult-child interaction. How has parenting changed your life as an artist?

FLAKE: I’ve had to become more efficient, time-wise. I really don’t know how I ever looked at my week and was like, “Oh, I’m so busy.” It’s made me a slightly less appalling waster of time. And I also spend a lot less of my life hung over, which is helpful.

GEHR: That’s a benefit people rarely cop to.

FLAKE: I figured out that I spent almost two months of the year incapacitated. And I realized that maybe that’s how people realize they have a drinking problem. Parenting keeps me way more on the straight and narrow.

GEHR: You named your daughter after Lynda Barry’s semiautobiographical character Marlys.

FLAKE: I did, yeah. I did a writing workshop with her in Chicago a million years ago that was amazing. The four-panel format is certainly present in her work. I have loved her so very much for so very long, and I love the character of Marlys so much that I couldn’t think of a better role model. I’m stealing a lot of her ideas for the cartooning course I teach.

GEHR: Do you have a philosophy when it comes to cartooning pedagogy?

FLAKE: I do. I feel like it’s very much a work in progress, and there’s no better way to feel like a fraud than to try to teach something. I do a lot more in terms of idea generation and writing prompts and ways to come up with cartoons than a lot of technical stuff. I touch on technique, but I feel it’s much more important for them to have ideas they’re excited about and want to work with, and that style and technique will follow that. Idea generation is the most important thing.

GEHR: What do you cover?

FLAKE: It’s a gag-cartooning class, but I split it into two segments: gag and then longer-form cartooning, because I think there’s more of a market for one- or two-page things. Gag cartooning is a weird dark art, and people who might be really good at cartoon narratives might not necessarily be good at gag cartooning. So I wanted to make it more universal. My role as an instructor is less about teaching them “this is how you make cartoons” than trying to sort of midwife out the cartoons they already have inside them, giving them space and permission. Continuing-ed people aren’t necessarily art students per se. They are not constantly encouraged or expected to draw. And I think they need that space and permission an undergrad might not.

GEHR: What other cartoonists have you admired the most?

FLAKE: Shary Flenniken is a huge influence. National Lampoon was around a lot and I loved it as a kid. Completely age-inappropriate. I loved Trots and Bonnie and now realize it’s a stronger influence than I ever would’ve thought at the time. Her work was burned into my brain. Her juxtaposition of the cute and the profane laid a real base for Lulu Eightball. I’m a huge Flenniken fan and feel she should be rediscovered. She wrote the introduction to the second Lulu collection and was very nice about it. She’s amazing. There are a lot of amazing comics people in Chicago, of course, but they aren’t influences so much as people I love and admire. People like Chris Ware, Ivan Brunetti, Laura Park, and that whole insanely talented scene.

GEHR: Anyone else you think might be criminally underappreciated.

FLAKE: Tim Kreider? mean, he’s sort of really rocketed as a writer. He’s a brilliant essayist, but I was a huge fan of his cartoon work. The Pain started when I was in college and was a big “Oh my god I love it!” A lot of the people I’m particularly fond of are not laboring under rocks, per se.

GEHR: Any younger cartoonists you’d like to champion.

FLAKE: How young? My daughter is doing amazing work. [Laughter.] Ed Steed is basically a fetus. He just dropped out of nowhere with this monster cannonball talent and he’s just un-fucking-believable. He’s a sweetie. He’s got this sort of wide-eyed English diffidence, but he’s a sweet and intelligent human being. He’s got layers.

GEHR: Indeed. He makes your eyeballs work harder than almost anyone these days. You have to make complex connections to get the joke.

FLAKE: He’s an instant classic and it fills me with the blackest of bile.

GEHR: Nah, you two are apples and oranges.

FLAKE: Yeah. But man, sometimes it would be so great to be an orange.

GEHR: Read any good books lately?

FLAKE: I have. I feel I should be more ashamed of liking Elizabeth Gilbert, but I’m not. You know what else I like? Billy Joel! But Gilbert’s new book on the creative process is great. It’s a very helpful and joyous book people should read. I’m also reading a book by my friend Kate Christensen called How To Cook A Moose, which is an awesome memoir of living in Maine and eating...moose. Not to keep name-dropping, but my friend Jami Attenberg wrote a book called Saint Mazie, which is one of the best things I’ve read in a very long time. What else have I been reading? I’ve been reading Facebook a lot.

GEHR: God, that’s the best.

FLAKE: Yeah, it’s such a good book.

GEHR: It always leaves you wanting more.

FLAKE: Weirdly enough, I just read a book called The End of Loving that my dad randomly gave me. It was a library discard by a writer named B. J. Chute, and it’s lovely and sad story about a love triangle in New York, written in the early fifties. My dad read it and liked it. It was nice that he handed me that instead of The Road To Serfdom, which is another thing he’s trying to get me to read. We differ in our politics, so it was nice to be handed a novel that wasn’t by Ayn Rand.

[Big transcription thanks to Erin Keaton and Emily Silva.]