Adrian Tomine’s Killing and Dying culminates with the titular story of an aspiring stand-up comedian and her relationship with her parents; mostly with her father. Without the context of stand-up comedy, the title would forebode something more macabre than we get, but that linguistic irony specific to good stand-up comedy is an appropriate metaphor for Adrian Tomine’s work. Like a good bit, his stories have a just amount of self-awareness, and they only work if we understand the comedian is part of the joke. Long-time readers know that as a storyteller, Tomine can be responsible with his victims as with his victors. This time, the characters include a temperamental artist, a woman who can’t shake her porn star doppelganger, a victim of domestic abuse, a victim of self-abuse, but these characters feel darker. Perhaps because there’s no Tomine archetype to show us the brick wall behind him. So…where exactly is Adrian Tomine?

Adrian Tomine’s Killing and Dying culminates with the titular story of an aspiring stand-up comedian and her relationship with her parents; mostly with her father. Without the context of stand-up comedy, the title would forebode something more macabre than we get, but that linguistic irony specific to good stand-up comedy is an appropriate metaphor for Adrian Tomine’s work. Like a good bit, his stories have a just amount of self-awareness, and they only work if we understand the comedian is part of the joke. Long-time readers know that as a storyteller, Tomine can be responsible with his victims as with his victors. This time, the characters include a temperamental artist, a woman who can’t shake her porn star doppelganger, a victim of domestic abuse, a victim of self-abuse, but these characters feel darker. Perhaps because there’s no Tomine archetype to show us the brick wall behind him. So…where exactly is Adrian Tomine?

Ishii: There are several unique styles and formats in this collection. Were your stories written in the order in which they appear, or have these pieces been written at different times, then edited for each Optic Nerve issue, then re-issued in this suite? Could you say a little bit about how you organized the stories?

Tomine: The stories are arranged in pretty much the order that they were written. I think a few successive stories might've been swapped in terms of placement, because I know I wrote an early version of “Amber Sweet” before I wrote “Hortiscuplture.” But I was, in some ways, organizing the book as I produced it. A lot of the story ideas existed in my mind and in rough form in sketchbooks, so there was some consideration put into which story I chose to draw next.

The letters (that you publish in the original Optic Nerve issues) always make me laugh out loud. Talk about killing and dying…

Yes, some of my colleagues have told me that the letters page in Optic Nerve is their favorite part of the comic, and I can understand why. I always enjoyed that part of other people’s comic books, and I miss it now that the “graphic novel” has become the dominant form of publication.

I’d say it is analogous to online comment culture.

I actually think it's a little different because it doesn't have that hair-trigger immediacy. It takes more time and effort to hand-write a letter, put it in an envelope, get a stamp, etc. Of course that doesn't mean that the letters are necessarily less critical, but they might be a little more thought-out, or in some cases, way more in-depth and personal. Also, there’s such a long time gap between issues that when a letter finally sees print, it’s commenting on something from like two years ago.

Why don’t the letters make it into the collections?

Don’t you think that would be kind of weird to print letters in the book? For a lot of readers, the book is their first exposure to the stories. They don’t know anything about Optic Nerve, so they’d be like, “Wait, how are people already responding to this, and why is it in here?”

I guess I like the letters enough to think it’d make a good “secret track”…but actually, do you feel like you want to keep your graphic novel readers and Optic Nerve readers to stay compartmentalized? Or is it sort of one of those things where if someone is seeing your work for the first time you want it to be in the GN format pure and simple?

It’s a lot less calculated than that. I don’t have any grand plan for compartmentalizing readers. It just never occurred to me to print the letters in the books, but now that you bring it up...well, it still doesn’t seem like a good idea to me! Sorry.

I’m happy that for a long time--years even--all this material was basically exclusive to comic book stores and their patrons, and I think it’s nice that there are a few little things that will only exist in the comic book format. I’d love it if all of my favorite cartoonists still serialized their work and I had a reason to go to the comic store every week.

How do (the letters) affect you, personally? Are you as entertained by them as say me, and do you have emotional distance from them or is that impossible because they’re talking about your work?

I've been inviting and encouraging this kind of correspondence for so long that I have a slightly different response than I did when I was just starting out. I have found that people who write to me tend to have opinions that skew towards extremes, so I can go through a batch of mail and sort of take all the compliments and criticisms with a grain of salt. And I think I've actually learned a lot from the negative letters. There was a point a few years ago where I felt like I was on the verge of becoming blindly defiant, like "These idiots don't know what they're talking about!" But fortunately I was objective enough to realize that a lot of these quote unquote idiots were making some of the same points independently, and I felt like there was some significance to that. I know that sounds like the lamest kind of artistic pandering, but I honestly think the effects on my work are better than if I had just buried my head in the sand and dismissed anything that wasn't praise.

Would you say there’s any particularly poignant or frequent criticism you’ve received through consumer-readers (as opposed to say, editors) that has influenced you more profoundly than others?

Oh, where do I begin? I think the first big criticism was the clarity of my influences. Or more specifically, that I was “ripping off” certain artists. And then something that came up later in my career was the sense that I was treading the same path a little too much, writing within too narrow of a scope in terms of tone, characters, settings, etc. Those were probably the most significant ones, and they were points that, on some level, I knew to be valid. And I don’t want to make it sound like I’m patting myself on the back and saying “mission accomplished” or whatever. I know these are ongoing struggles, but it’s definitely helped to at least try to address them head-on.

You’ve written different facsimiles of yourself in the past, so I wonder what you think of the relationship between artist and art, artwork and audience. Killing and Dying is so interesting from the perspective of your oeuvre, because it’s not scenes from a world the reader might ascribe as yours personally, but can you extrapolate on where/when/how did that shift happen, and how you engage yourself with readers as an artist versus as a subject?

A lot of what I was doing with Killing and Dying was a direct response to Shortcomings, and one of the things that I kind of regret about that book was the way I intentionally blurred the line between my own life and the fictional story. Of course for most readers it didn't even cross their mind, but I know that at least a few people who had been following my work over the years were very interested in how much of that story was autobiographical and how much I was like the main character. And they weren’t curious because they loved that character so much! I ended up feeling like it was a distraction. So with Killing and Dying, I made a conscious decision to write about characters and situations that, at least on the surface, were very different from myself and my life.

You’re a dad now, and there’s a parental theme throughout this collection; an incredibly fraught one. The paternal conflicts are especially prescient in “Go Owls!”, “Hortisculpture,” “Killing and Dying.” You’ve mentioned these conflicts probably reflect your own fears as a husband and father, in a recent New Yorker interview. I’m curious, what has your wife-baby mama said about these stories?

My wife's tastes as a reader are more highbrow than mine, and in general, I don't think she has a lot of interest in angsty stories about twenty-somethings fallling in and out of love. So even though she's always been very generous and polite in response to my work, I believe her when she says that these are her favorite stories of mine. She also puts a very high premium on humor, both in life and in art, so I think she appreciates that these stories, while kind of dark and melancholy in some ways, are also at least striving to be funny.

Have you gotten feedback from other family members? I suppose your daughters are much too young for this but have you seen any kind of visceral response from them to your artwork?

Yeah, my daughters are certainly too young to actually read the book, but my oldest daughter is savvy enough to recognize any character that seems like a daughter or a father in anything I draw, and is always asking, "Is that supposed to be us?"

I don’t suppose your own parents has had anything to say?

Wait, why wouldn’t you suppose that? My family has always been very supportive and encouraging of my work from day one.

It’s funny, I rephrased this question a few times in my mind but what I really wanted to know is if your father had anything to say about the father characters. I also don’t assume any parent would have the guts to honestly expound their interpretation of kids’ work (unless they’re incorrigable stage moms), so my question is more about whether they’ve given you an interpretation, beyond filial support?

I’ve had plenty of interesting, in-depth conversations with my family members about my work, definitely beyond just general support. I’m sure it can be awkward for them occasionally to read something of mine and then be obligated to respond to it, but I’ve been putting them in that position for so many years now that I think it’s really not a big deal. They’ve been great, and I’m sure I’ll look to them for inspiration in this regard as my daughters get older.

I might suggest you’re also a comics dad, now, in that you’ve been around for a while and have had time to exert influence on younger artists. Do you consider yourself a purveyor of influence? Do you see intellectual “children” of your style in other comics? Any rip-offs? Do you/have you taught? Have apprentices? Like any up-and-comers you think work in the same universe?

No. I think that I'm so much the product of my own influences, that it wouldn't really make sense for me to influence anyone else. If anyone's artwork slightly resembles mine, I'm sure it's because they studied the same great artists that I did.

You’re so self-effacing! I do wonder though, are you interested in imparting your style, however much the product of influence, to others? Do you think even liminally or deliberately, for example, your daughters are thinking of going into comics or illustration?

No, it really doesn’t occur to me. In fact, some times my older daughter will ask if I can help her with a drawing, and I’ll be reminded of like, “Oh, actually I probably can!” I think there’s so many things that are more important to focus on as a parent, and in some ways it feels kind of creepy and narcissistic to try to cram comics or illustration down my kids’ throats. I’ve actually really enjoyed approaching things like personal taste or interests in the opposite direction, where I end up learning about something that my daughter discovers on her own and brings into the house. Actually, sometimes that’s really brutal and I have to kind of grit my teeth, but I still feel better about it than brainswashing her into being a little mini-me.

And in terms of other cartoonists, to be honest, the last kind of comic I’d want to read is something that’s been heavily influenced by my work. Maybe it exists and I’ve just avoided it, but I’m much more excited by newer cartoonists that seem to be bringing in all kinds of influences that I couldn’t even begin to identify.

Can you speak to the awkward identity politics of your characters? “Hortiscuplture,” for example, features the most complicated character in terms of ID politics. He’s kind of racist but in an interracial marriage and can be despicable but is also pathetic. Has he learned a lesson? Was there a lesson? Where did this character come from? How would/do you interact with him in real life? Is the lesson that we can figure out the moral complexities of your characters on our own?

I think you come down on that guy a lot harder than I do! I tried to show some different facets of his personality, but overall I felt a lot more empathic than critical towards him. But what I've learned from publishing books and going out on tour and meeting people that have read those books is that my opinion on this stuff is the least important one. If someone reads "Hortisculpture" and says, "He's kind of a racist and he's despicable and pathetic," it's not my place to argue.

Ha. I’m sure I’m coming down on him harder because half the story is also about how depressed his wife gets. Poor gal!

Ha. I’m sure I’m coming down on him harder because half the story is also about how depressed his wife gets. Poor gal!

Good point, Yeah, of course she’s probably a much more purely sympathetic character. I pity anyone who’s yoked to a tempermental artist, successful or not.

I’m just noticing now, actually, as I think about the male POV in these stories, there’s a literal coloring that takes place when shifting from male and female perspectives. Is it possible your use of color may be meant to call up some kind of feminine anima, given that “Amber Sweet” and “Translated…” are so much the stories of women and in full color, and then the slightly more muted (color-wise) “Killing and Dying” is about a girl’s coming of age? I realize there are color spreads in “History of Hortisculpture” but…I’m asking this question anyway.

I hadn’t thought of that, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t possible. I’d say more often than not, decisions were made about the construction of these stories on a purely intuitive level, so who knows?

Also re:moral irony, these characters' conflicts are resolved ambiguously and we’re left wondering if things work out for them. I find that’s what makes your stories so successful, but I’d argue it works against a current trend in American literature today where we expect writers/artists to be very upfront about their politics. The ambiguity is almost certainly a statement itself. Is it? Do you have something to say about the culture of saying something?

Also re:moral irony, these characters' conflicts are resolved ambiguously and we’re left wondering if things work out for them. I find that’s what makes your stories so successful, but I’d argue it works against a current trend in American literature today where we expect writers/artists to be very upfront about their politics. The ambiguity is almost certainly a statement itself. Is it? Do you have something to say about the culture of saying something?

I totally understand that resistance to ambiguity, and the idea of audiences wanting artists to come right out and make a clear moral statement. I think there's certainly a place for that, and I think some art is completely built around that act of making a statement. Having said that, in general that's not the kind of art I typically gravitate towards, and I guess it stands to reason that it's not the kind of art I make. At least for me, it's hard to reconcile the goals of being didactic and presenting life in an honest, realistic way. I think if an artist can genuinely reflect the experience of being alive in some way, that's still saying something.

What about the interpretive significance of divorcing the artist from their artwork?

It does seem like there is definitely a heightened interest in the relationship between artist and art these days, and I don't think that's such a good thing. I actually think it would be great if people knew less about the people who created the art and just focused on the art itself, but I don't see our culture shifting in that direction. I’m not sure, but I almost feel like a certain spark was lit when DVDs first started including "bonus material." It really seems like there's not a single book or comic or movie or album that comes out now that isn't eventually accompanied by "behind the scenes" features or an interview about the “making of” process or whatever. I'm a participant in this phenomenon myself, so I understand why it can't really be stopped: I feel an obligation to help promote my book, and the opportunities to do that usually involve talking about my personal life or showing how the work was created. This inteview is getting so meta!

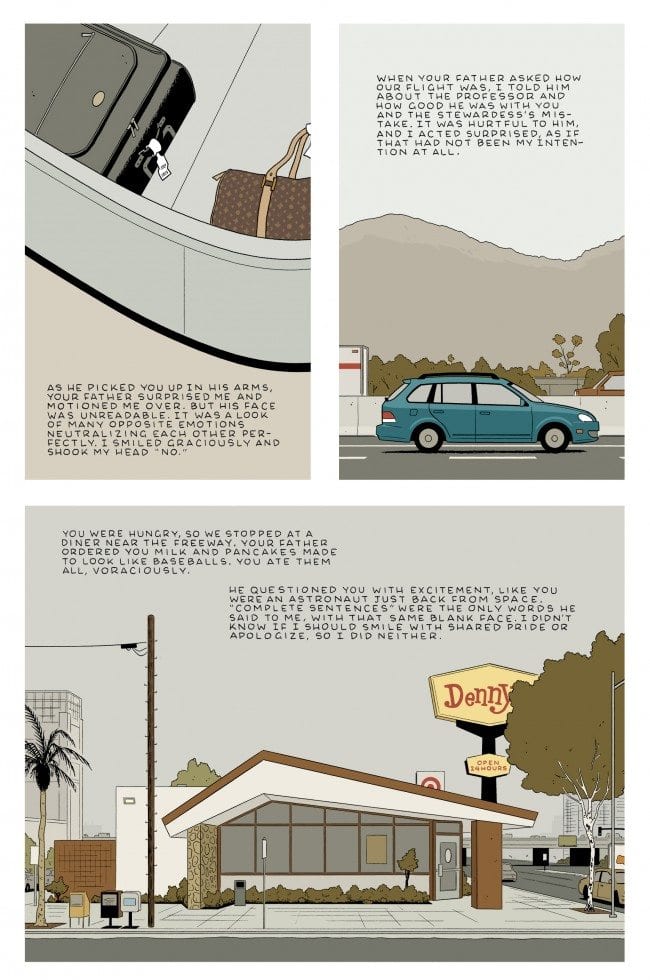

OK, switching gears completely…Denny’s! Can you tell me all about what Denny’s meant to you, because it has a foreboding presence as the backdrop in several of the stories, to say nothing of the cover. In the interest of full disclosure, Denny’s was a locus of extreme feelings for me growing up, because there was one adjacent to my high school. What is it about Denny’s that made it important enough to be recognized in your stories? Is it of personal significance or is it more about its look, like the ubiquitous diner in Tarantino flicks?

One of the more vague, important-only-to-me kind of endeavors of this book was to capture a certain mood or atmosphere that I associate with California. And the parts of California that I grew up in are not the typical beach towns that we see on tv or the cosmopolitan cities like San Francisco or LA, but smaller, more suburban places like Sacramento and Fresno. Now that I live so far away, I realize that for better or worse, those are the kinds of towns that really feel like home to me, and conjure up really vivid emotions and memories. So even if it's only on a subliminal level, I tried to infuse this book with those feelings, and part of that was done by including some very specific settings and background details. Also Denny’s paid me a ton of money for product placement. Just kidding!

Lastly, do you feel your emotional dialect has changed with your sensibility for “home”? Do you feel like it’s still a move/transition or is California fully fully in the mental cedar chest? Because I mean, there aren’t any Denny’s in NYC, for example.

There's actually a Denny's down by Chamber Street! But it's really not the full experience if you aren't in a giant parking lot surrounded by strip malls and freeways.

Do you get homesick? Is there an East Coast v West Coast situationalism for you at all? Biggie or Tupac?

I think I've accepted the fact that California will always feel like home to me, and that I'll always feel like a West Coast transplant in New York. And that's no indication of which place I like better or where I enjoy spending my time or whatever. It's just something I'm aware of, and it hasn't changed at all in the twelve years since I moved.

So, Tupac.