On Nov. 6, 1972, Bill Griffith, the famed underground cartoonist and creator of Zippy the Pinhead, was sitting in a hospital, waiting to hear news about his father, who had been injured in a cycling accident.

On Nov. 6, 1972, Bill Griffith, the famed underground cartoonist and creator of Zippy the Pinhead, was sitting in a hospital, waiting to hear news about his father, who had been injured in a cycling accident.

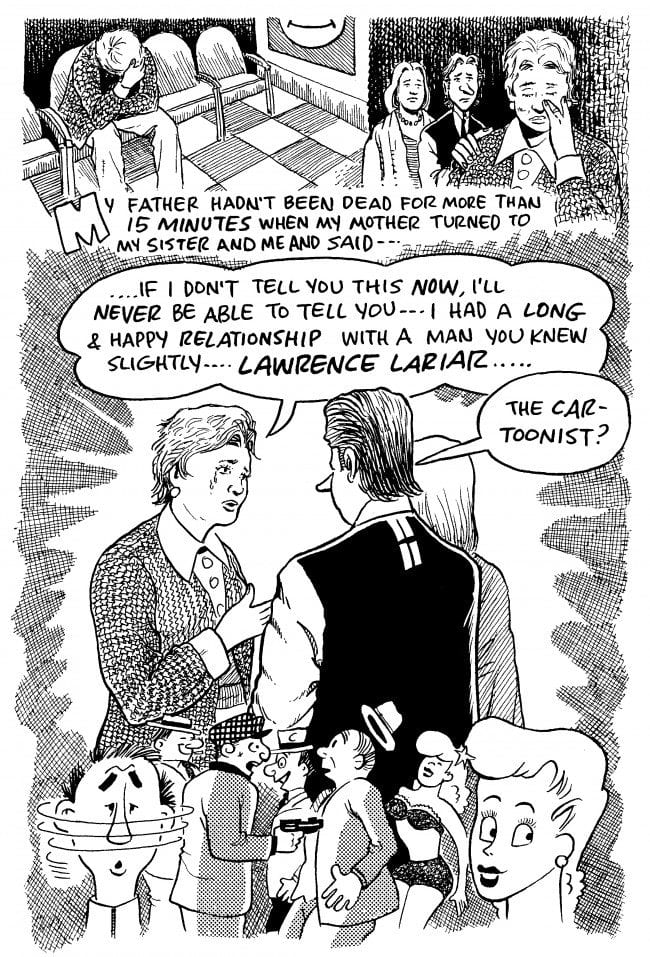

The news was not good. Griffith's father had perished in the accident. But before Griffith and his sister had even a moment to process that news, their mother almost immediately confessed to both of them that she had been having a lengthy affair with a somewhat illustrious cartoonist known as Lawrence Lariar.

Griffith’s attempt to come to terms with this revelation all these decades later, as well as to try to understand his parents better, is the subject of his latest graphic novel, Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair With a Famous Cartoonist. It might be Griffith's best work to date, an emotional, intimate, and almost startlingly sympathetic look at the secrets we hide from our family and how we often fail to see our parents as fully rounded people, ultimately to our own detriment.

I spoke with Griffith about the book as part of a Q&A panel during this year's Small Press Expo. What follows is an edited (for clarity) transcript of that discussion.

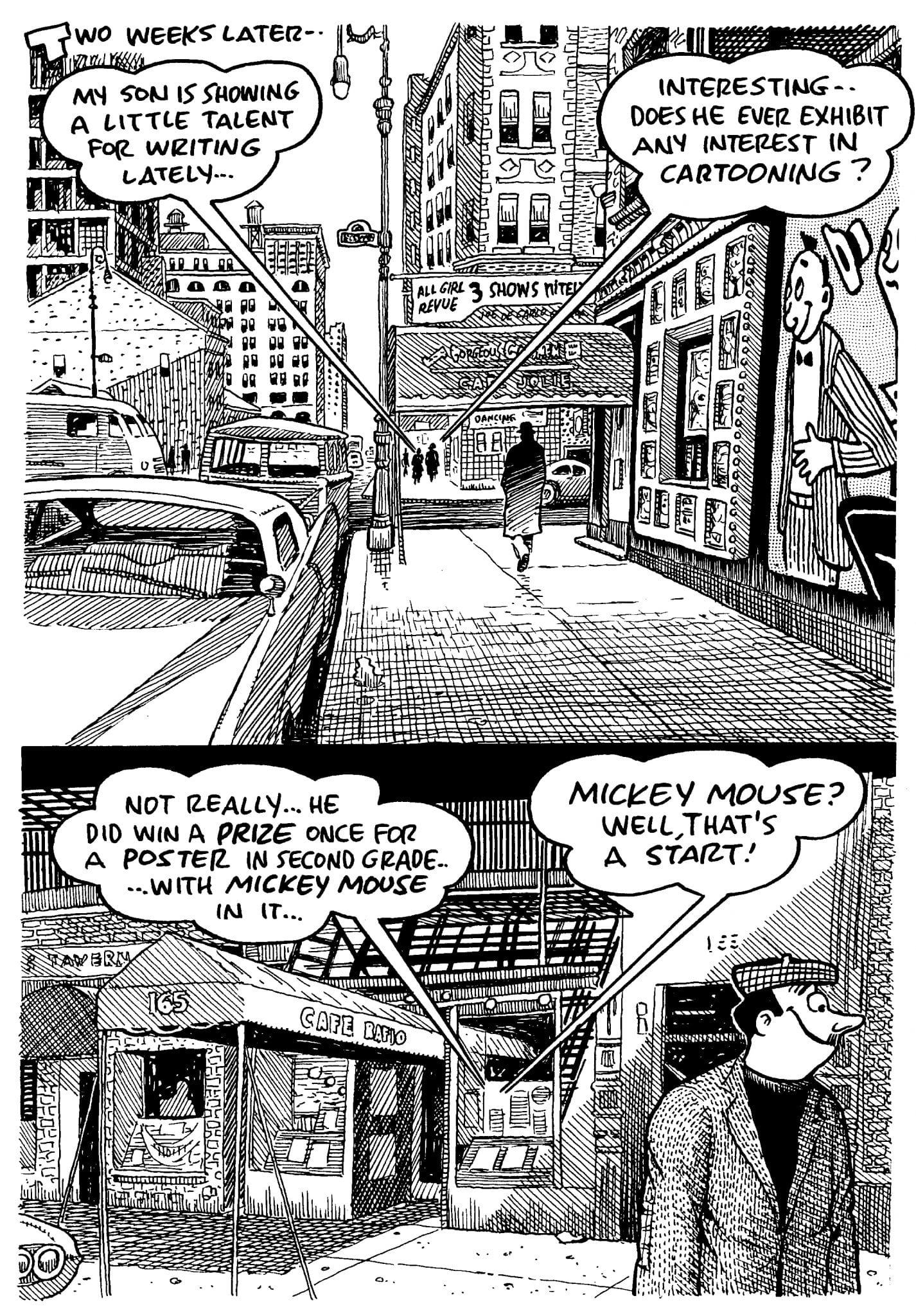

Chris Mautner: So to start with, this is an image you sent me from a 1974 issue of Young Lust with a page you did where you’re portraying an affair between a cartoonist and a woman. Obviously this is something that had been percolating in your head since you first learned of it. But what was the point where you said, “I have to tell this story, not just come at obliquely, but I have to directly tell my mother’s story?

Bill Griffith: Well the trigger for it was a visit to my uncle. My uncle is my mother’s brother and still alive at 91. Three and a half years ago – this is in the book, this is how the whole thing started – he sent me a letter hinting that he would like me to come visit. And I did. I thought, "He’s getting old, I’m not going to see him a lot in the future and this is a good time to visit."

In the course of the visit one evening, his wife, my aunt, said, "Do you think your mother ever had an affair with—" ... she said a name. And I said, "Not too likely, he was our neighbor. But of course she did have a long affair with Lawrence Lariar." And both my uncle and my aunt said, "Who? What?" And I explained, and they were kind of OK with it. And I thought, "Wow, I thought they were going to be outraged." These are conservative people. But underneath all conservative people is a not-so-conservative person and that came out.

I was staying at a hotel nearby. My aunt was very sick, so I didn’t want to stay with them and bother her. So I went back to my hotel that night with this conversation in my head and the book was born in about a four-hour frenzy. I was up 'till three in the morning just scribbling notes, going online, looking up this guy who I had never researched at all. I knew when I was a kid that my mother worked for him as a secretary. And I knew he was a famous cartoonist. But I only had one meeting with him, which is in the book also. So my relationship to him was very slight.

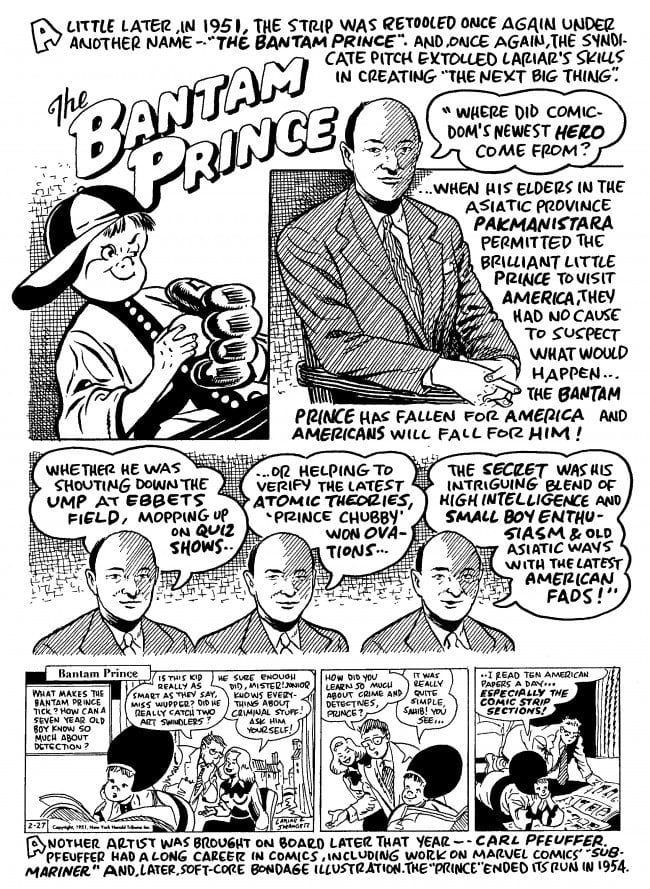

But when I did the research I said, “Oh my god, this guy has done everything in comics”. He worked for the very first comic book, New Fun, in 1934. He had four daily strips. He wrote three how-to-draw cartoon books. He wrote gag cartoons for every magazine from the 1920s to the 1970s – a huge career that’s been completely forgotten. [To audience:] Anybody every heard of Lawrence Lariar? Anybody? [A few people raise their hands.] OK, If this was 1953, you would have said, “Oh yeah, that guy.” He was in Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Look. He was primarily a gag cartoonist. So this book just sort of blossomed out of that meeting with my uncle and aunt.

Had you ever entertained the possibility of trying to do that story beforehand?

Well, you showed that strip from 1974, that was my one previous and only attempt. My mother confessed her affair to me as was explained, right after my father died. He died in an accident. We were in the hospital, the doctor comes out, says, "Sorry, we couldn’t save him.” My mother turns to me and my sister, and says, “I have to tell you this now because I’ll never be able to tell you again: I had a long and happy affair with a man you knew slightly.” And she said his name. And my sister and I just looked at her like, “What planet are we on?” We were in total shock. We weren’t even grieving yet, it was just after he died.

So it just sort of stayed in the back of my head. And as with most kids of their parents, you don’t ask questions. I could have asked any number of questions. She came out to live in San Francisco in 1980, partly because I was living there. And we became very close and I could have asked her all sorts of things, but I never did.

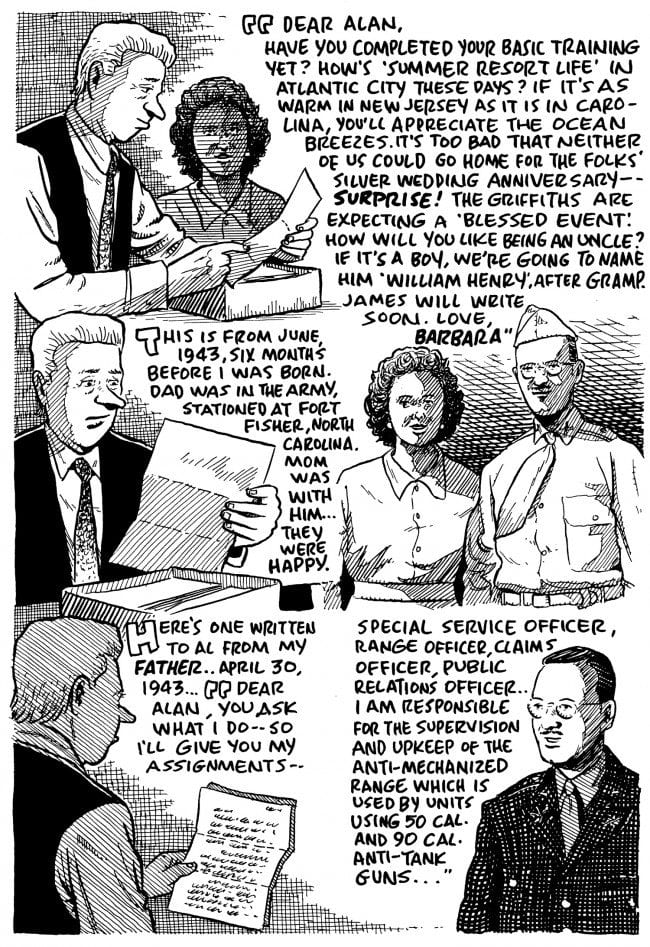

But when she died she pointed to a filing cabinet, just the day before she died, and she said, "Throw everything away but that. Keep that.” It took me awhile to examine that filing cabinet. There were diaries, letters, a long unpublished novel – she was a writer – all about the affair. So I had this huge trove of material to work with.

Now you said the story came to you fully formed. Did you go through revisions? Did the voice change at all?

Well, then the structure has to happen, you know. You’re writing a book you have to worry about structure. I decided to not do it chronologically but to weave in and out of the past and the present.

So I have a narrative device in the book where I’m talking to my wife, the cartoonist Diane Noomin, and that happens every so many pages so it comes back to the present that way and then it goes back into the past. And then I have a whole “what if” section – what if he had been in my life as a father? What if my mother had divorced my father and married him? This was a cartoonist who taught comics, who had a cartooning school. Who asked my mother several times, should I mentor him? She said, “No!” [laughter] "Please!” This is a 16-year secret affair conducted while she was married in Levittown, Long Island. The affair took place in New York in a hotel. Sometimes in motels but usually in this one hotel on 43rd and Lexington. Sixteen years. Did my father know? How could he not? But I have no evidence of it. Once again, he died before I could have asked him that.

I want to touch on that and [your] family history, but one other thing I wanted to touch on early is that this isn’t your first attempt at autobiography. Even though you’re known primarily for Zippy, which has a healthy appreciation for dadaism and the absurd, you have attempted to delve into your family history before.

Yes, I have.

And in pages of Zippy, I believe, you did a story about your relationship with your father and how troubled that was. Do you feel an affinity for nonfiction, for biography and autobiography, and how does it differ from your approach to Zippy?

In 1976 I had been doing Zippy for about six years in underground comics and in a weekly self-syndicated strip. And Art Speigelman told me that he liked Zippy, but that it was a little bit like being stuck in an elevator with a crazy person [laughter]. And by that I took that he meant that maybe I should change things a little bit. What I thought was, “Ok, Zippy is an absurd comic character. Maybe he needs a partner who’s his opposite.” And I thought, “Well, that’s me.” I’m very opposite from him. Zippy is my inner weirdo, but I’m not that way. If I was that way, I couldn’t drive or pay the rent. So I created Griffy. Griffy had been sort of there a little bit before then but I decided to make him be Zippy’s partner in comedy. Once I did that, the leap from to doing autobio material ... was a natural outgrowth of that. So that’s where that happened.

Did you see the book at all as any sort of – I’m hesitant to use the word catharsis – but was there any kind of bibliotherapy going on for you? And to what extent were you conscious of that?

Oh yeah. How could it not? Here I am, bringing my mother back to life with the constant feeling that she was in the studio with me some of the time. I had a dream one night when I was halfway through the book – it’s in the book – where I came down to the studio and she was in a sleeping bag, sleeping on my drawing table [laughter]. I tapped her on the shoulder and she said, “Oh, that refreshing. Get back to work, see you later.” So I took that as an approval. I took that as a nod of approval from her. But yeah, sure, I had moments where I just broke down crying, while I was doing the book. Many moments like that.

Well that’s where I wanted to lead into with this because one of the really interesting things about this book for me is how you portray yourself throughout it. You’re never coming at it from a point of anger, or from a point of frustration – maybe not resignation but the main central driving force here seems to be curiosity and a desire to understand, which I thought was an interesting approach. I think a lesser book would be more from a point of your wounds and your hurts. And you seem to studiously try to avoid that, although you’re very much present in the novel at the same time. Were you concerned at all when doing this story, about how you portrayed your feelings towards your parents and how your feelings about the story might affect the narrative?

I don’t think that ever happened. I had the same attitude that my aunt expressed when she said, “Good for her,” when she heard about the affair. My sister on the other hand has a very different feeling about it. When I showed the book to my sister, she looked at it and said “We have very different ideas about our mother.” [laughter] I won’t go into that in great detail, but she didn’t have the same feeling of “good for you” at all. In fact, she felt that my mother had betrayed my father. I don’t feel that way.

This is being billed as your first – I’m using the term Fantagraphics used – "long-form graphic story." Was the length and ambition of this project a challenge for you in any way?

No, because at first it felt like I was getting back to my underground days, when I would do 10-page stories and 12-page stories. I felt like I had been damning up that urge for years. Sometimes in Zippy I’ll do what amounts to a long, continuing narrative that goes on for days and days and if you read it all together it is a narrative – a long narrative, but not the way a narrative feels when it’s done specifically for the long form. In a daily strip format you have to break it up, it feels self-contained. Every four panels has to feel like you could read it without knowing what happened before or after. Doing a long-form graphic novel is exactly like writing a novel. It requires a lot of concentration and thought about structure, continuity.

I have incredible, grateful feelings towards my wife Diane for being a really great editor. When I would bring the three pages up that I did that weekend and she would say, “You know what, there’s a bump between this page and the next page. There’s a glitch. Something is off.” Which I didn’t see.

Even at this point in my career – I teach comics and I teach kids about continuity and how everybody does things with continuity that make presumptions on the reader. You can never make a presumption in comics. You have to spell out what you’re doing very carefully and clearly without being didactic. That’s the tightrope walk you have to do. And you need someone with an outside view to tell you when you’ve made a glitch, when you’ve made a bump in the continuity. And so that was very different from my normal daily strip activity.

But once I started doing it, it just flowed out. I still had to do Zippy five days a week – meaning seven strips – so this was all done on weekends. This entire book was done on Saturdays and Sundays.

I wanted to ask you about that, about the difficulty of juggling an ambitious project like this while you still have a daily job to do.

Well, luckily Zippy just rolls out of me every day. I get up about 9:30 a.m. and I go for a walk – about a mile-and-a-half walk. Inevitably, when I come home I have at least one if not three strip ideas. A walk literally jogs them out of my head. I write them down while I’m walking and I come home and I do either one or two Zippy strips. It’s a little bit like writing in my diary.

It’s that easy for the most part. Once in a while I’ll sit at the drawing table and say “Uh-oh, I have no idea what’s next. Is it all over?” But that lasts about 10 seconds. Zippy and the other characters in the strip literally talk to me. Not in a schizophrenic way. And they say, "It’s time for me. Do a strip about me. I’m Shelf Life. You haven’t done me in six months." And so I just listen to that voice.

Zippy also, I think, often plays upon this idea of a lost America that’s slipping away, especially with a focus on kitsch, iconography. There was a run where you were focusing on the kitsch architecture of the 1950s and '60s. I think Invisible Ink ties into that a little. I think one of the central themes of the book is this idea of a slipping away of lost generations. You mentioned not talking to your mother, not talking to your parents and then you have this desire where you want to know more but the opportunity is gone. That seems like a central, even on a grander scale, that there are memories – so there’s this tension in the book between the modern day and yesteryear that’s lost. Right away in the beginning, you’re talking about how you don’t get letters anymore.

You’ll notice at the opening page at the bottom, I’m on my way to the post office and I’m worried about the list of things to be worried about, and Donald Trump is one of them. [laughter] I wrote that three and a half years ago and when I wrote it I thought “Gee, is he going to be a figure of ridicule? Is he still going to be around in a media sense in three and a half years?” Thank you Donald! [laughter] Donald is a gift to me every day as a cartoonist. [laughter]

But is that an important issue for you, especially working on this book, that idea of time lost?

I was very aware that I was not just dealing with the narrative of my mother’s affair but the times in which they took place. I don’t think that affair could happen today in such a way. There’s too much lack of privacy, too much exposure. In the 1950s and '60s, you could still have secrets and do things in hotel rooms and motel rooms and not be caught. I think today it would be almost impossible. Especially if your spouse was suspicious. In those days you would have to hire a detective if you wanted to investigate that kind of stuff. But yes, I like to get lost in the past in my strip and in this book. It was part of the appeal of the book, to regenerate the times in which the narrative took place.

Can you talk a little bit about the research you did? Because one of the things I find interesting is that you detail the research in the book as it’s happening.

Yeah, when I started the book I just had my memory of my mother confessing this affair to me briefly in 1972. I knew that there was stuff that she had left me in that filing cabinet but I hadn’t quite looked at it yet. So there’s the first treasure trove. She left two diaries, one of which the affair was discussed. On the front of it, it says “To Bill and Nancy”. Nancy is my sister. So people ask me about my mother, “Would she be embarrassed by this book?” Well, hard to say but she definitely wanted me to know the story.

So I had that material. Then I started doing online research, which is of course wonderful. Go to Google images or Bing any time now or whenever you want to and put in the name “Lawrence Lariar,” you will see hundreds and hundreds of pages and images. Interviews, bios, articles, a huge amount of material.

While I was researching that, I came across something that said, “Syracuse University Library.” That was the source for a particular article. So I called Syracuse University and I said, “Do you have the papers of Lawrence Lariar by any chance,” and they said “Yeah.” I said, “Has anybody ever asked for them before?” She said, “No, you’re the first one.” [laughter]

He left them himself over a period of four or five years in the late 60s. I couldn’t get why he did that. He has no connection that I know to the university. But I went up there and spent a couple of days looking through boxes with white gloves, original art, letters, scripts he wrote, he wrote scripts for early TV shows, this guy was … people think I’m prolific or overachieving? This guy was ten times that. I can’t imagine he had a minute to spare. He wrote 16 crime novels.

That was how my mother connected to him. He put a want ad in the local paper, in Levittown: "Wanted a part-time secretary for a crime writer.” Didn’t say cartoonist. And my mother was an amateur writer, at that point had just been published a little bit, that was what she did. He would speak his novels and she would transcribe them and then she did all the grammar checks – my mother was an incredible grammarian. When I used to be with her in San Francisco, we would be somewhere, she saw a store sign with an apostrophe in the wrong place, she would say “Bill, let me get out.” [laughter] And she would go in and tell them, “You’ve made a mistake." [laughter] And they would look at her with a big eye roll and then she would go into the next store. She was a very skilled writer and she knew grammar left and right and syntax and all that stuff.

Anyway so yes, I researched Lariar. … Without [the Internet] would have been much more difficult. I bought every single book he ever either did or edited, dozens and dozens of books. He wrote three best-selling how-to-draw cartoon books, including one that was in my house.

That’s the other thing, see, this guy was my shadow father in effect. My mother and my father’s relationship was strictly mechanical. In fact, in her diary she talks about how her sex with my father … she uses the word "mechanical." I was happy to hear that they actually had sex. For my father’s sake at least. [Mautner laughs] …

So this guy … My father was a very smart man, well read, did not graduate college, but he was not a dummy at all. But he had zero interest in art of any kind. Art, music, any creative effort, zero interest. He didn’t look down on it, he just had no interest. Lariar was a cultured intellectual, a New York intellectual. You would never guess it from his comics, which were strictly boffo gags, guys and gals, real lowbrow actually. I can’t say I really love his comics very much. I like his crime writing, he’s a great crime novelist.

But Lariar in effect introduced my mother to a whole world of art music and culture through him. They didn’t just have a hot-sheet affair. They would go to gallery shows, museums, Broadway plays, movies, and all this stuff filtered into my house, from Lariar to my mother to me. I didn’t know. I didn’t say, “Hey mom, how come there’s a Picasso book in the house.” It was just there. And it was there because of him. And I poured over it and I got wrapped up in the whole world of art and comics both. Through him, without knowing that was happening.

Let’s talk a bit about Lariar. One thing I found interesting was you told me that you redrew all of his art for this book; you did not simply reproduce it. Why was that important?

It was an instinctual feeling. My best way to explain it is I wanted to feel that the book was all by my hand, every inch of it. Since I was going to refer to and show his work at all kinds of stages of the book along the way as I discovered it, if it was to be reproduced from the original source, just photographed and dropped in, it would be jarring, graphically. I faithfully reproduced everything he did. I didn’t try to make it look like my version of his stuff, but I thought I had to redraw it to feel like the book had a cohesive graphic feel. I also felt that I was possessing it that way. I have to admit that I was owning it in a way. Also and way in the back of my head I thought, “Do I have to get permission to do this?” I asked Gary Groth my publisher, he looked into it and said no, you don’t need permission, this is a legitimate research material use, but I just thought if I used his actual art work – he did covers, he did entire books of comics all his own. If you look through the book you’ll see his output is enormous and I felt I had to show it, because that’s really who he is.

Well, that’s one of the fascinating things for me. He’s kind of an enigma to the extant that we know what he did, we know his accomplishments, but as a person, he’s sort of an enigmatic figure portrayed only through the semi-autobiographical novel that your mom wrote. What’s fascinating is not just that he did so much but that he is someone who only maybe three or four people in the room know. Why do you think that is? Is it just the vagaries of time?

Ephemeral pop culture. No one likes to think of the present as ephemeral, but it is, in the same way the past was. The number of cartoonists that we are allowed to remember is limited. There were thousands like Lariar that we don’t know about. In many cases for good reasons. Lariar was not somebody you wanted to sit down with and read 40-50 years later. His crime novels hold up. They’re in the Raymond Chandler tradition. They’re wonderful. They’re a little bit over-the-top pulpy, but that’s good. I like that.

But his comics – he did four daily strips. One of them ran for four years. Terrible strips. [laughter] Only one of them did he draw by the way, he wrote the others. They were done totally cynically, which is why they failed.

I have all the materials from the publishers of those strips, all the promotional materials, a lot of correspondence that he wrote. These were calculated strips. “OK, Milton Caniff does Terry and the Pirates, I’m going to do Irving and the Pirates or whatever. He just decided to do stuff that he thought would be popular and make money.

My mother inherited some of this. She would do all kinds of odd things, [write] articles for Cowboy Magazine and Cat Lover Magazine. [I'd say] "I see you jumping all over the place, what’s up with that?" And she said “It’s all about the money. I want to be paid. If you’re not paid for your work, you’re not validated. It’s not real. You’re just jerking off somewhere. You have to do the work, get paid, have a check, so wherever they will accept me I will go.”

That’s exactly Lariar’s philosophy. He was after a paycheck. He was after making a buck. And that’s why he did what he did. So there’s no auteur. There’s a little bit of an auteur that sneaks into his crime novels. But in his comics? Nothing. [He did a] daily strip for four years about a writer of a … the main character in the book was a romance writer who can’t get a girlfriend. And he has a leprechaun appear to him and tell him to do stuff. You’re reading this saying, “What the hell is going on here?” [laughter] It’s much more obscure than any underground comic I ever did. It’s bizarre. And it goes on for four years.

And there’s that great sequence in the book where you have this – I wouldn’t call it a panic attack but a fear of what kind of a cartoonist would you have been if he had had more of an influence on you [laughter]. And you’re imagining yourself drawing Zippy the Pinhead in this way.

Lariar wrote three cartooning books. His approach to cartooning was the same as his approach to everything: Make a buck, do what they want, get it out there, don’t be too arty about it. In the book I imagine if he had indeed mentored me, as he suggested – by the way, I know this from my mother’s novel. My mother wrote a 84-page novel about a family saga, going back to her parents, into her life, all the way up into the late 1960s. I’m the only character in the family not in the book, which I wonder about. I’m kind of grateful [muted laughter]. My sister comes off a little bit complicated.

Lariar has two chapters. He’s named Maurice Greenwood. By the way, when I get to it, which will be in a week or so, I’m going to make this available on Create Space on Amazon, so you can actually buy the novel it will be some low price. I’m just going to scan all the typewritten pages of the book. For total completists who want to see what it is, you can see it. This occurred to me two weeks ago and it was almost like my mother talking to me again. She said, “OK, you did this book Bill, good for you, but what do I get out of it?” [laughter]

Well, in the book there are several sequences, in fact there’s a lengthy sequence where you pretty much have lengthy segments from the novel and from her diaries. How important was it for you to have that direct, unfiltered voice?

OK, there’s … I’ve read my book about a dozen times. Every time I come to whatever page it is, about three-quarters of the way through the book – about ¾ of the way through writing the book – I discovered in the back of one of the diaries a sheaf of yellowed newsprint, which I hadn’t seen before. I pulled it out, it’s typewritten and it’s a detailed confession of her affair. Not in a diary entry, just a stream of consciousness writing. It actually starts out stream of consciousness then it becomes very comprehensible, because she was a writer and talks about her dilemma after my father died. What should I do now? Will Lariar marry me? Should I ask him? She has another guy coming after her, who she married unfortunately. Lariar did not want to marry her.

But anyway, this whole thing came to me when I get to that point where I’m reading my own book I stop being analytical about my own work and it’s my mother speaking loudly. It’s a whole section of the book. It’s a facsimile reproduction of these pages, every single word. And when you read that, that’s my mother speaking, absolutely directly to you. Not through me, not through comics, just absolutely directly. Every time I read it it’s just a powerful thing to me. And I feel like she’s right there with me.

You talk about having her there and how emotional it was for you, but you’re also drawing her having an affair. Was there any feeling of embarrassment or awkwardness?

Oh yes.

Were you concerned about that?

I knew there was going to be the point, and I kind of knew when it was going to happen, where I was going to have to show sex. And to not do it would have been dishonest or weird, but squirming and wigglingly I did. Drawing your mother having sex … [laughter] there are two scenes in the book like that. It was very hard but it really … I didn’t have to redo it a lot, it just happened. I decided to use silhouettes somewhat.

Actually there’s three sections in the book, one is silhouettes. In my mother’s novel she has graphic sex. It’s not pornographic, it’s just sex in which she’s got orgasms and everything going on.

I had to do it too. I had to do it. And she gave me all the information. Like I say, the book goes back and forth between my assumption, my surmise of what was happening between them to literally the word-for-word descriptions from her novel, in which all the characters had different names but were clearly who they were. Being her son, I knew who every single character was. In her novel the affairs took place in her aunt’s house in Brooklyn. I knew just where that was and I show it in the book. It’s on Hendrix Street in East New York in Brooklyn.

In reality, I had one great interview with my old high school girlfriend, who just died. She was dying of ovarian cancer when I was talking to her. And I had been putting off this phone call for a long time, but I called her and I said, “Barbara, I’m doing this book on my mother. Can you tell me anything about her affair?” Because when I broke up with my high school girlfriend, she became best friends with my mother for the rest of her life [laughter]. They even were roommates for a time. So I figured, this is a very uncomfortable phone call, but I had to do it. And she said, “Yes, I can tell you, they had a hotel, the Shelton hotel on 43rd and Lexington and your mother would come into the city and they would have their affair and have dinner. And she would come visit me and sometimes stay overnight," and that was her excuse to my father, that she was staying overnight with her friend, my former girlfriend.

So I got all kinds of information out of the oddest source of all. That I put in the book too. I locate their affair in the Shelton Hotel. The Shelton Hotel by the way, I researched that. Georgia O’Keefe used to live there. It became kind of an artists’ hotel. But it was founded originally as what they call “The Gentlemen’s Hotel” – code word for where you can bring your secretary for an affair. It was rooms, just rooms, and it was all men. It opened up in the late 1920s. I imagine Lariar had relationships before my mother. During their entire 16-year affair though they were completely monogamous with each other and I have many, many sources to back that up.

So I found out all kinds of stuff through research that wound up in the book. I wanted the book to feel that it took place in the real world and that it was not made up, even though some of it is my imagining, but that everything has a reason.

That brings me to my next question, which is that the book is very meticulous in your art style and providing a sense of place, and I can tell that’s something that’s important to you. It's important [to you] to get that sense of time and place. Even in Zippy, I always feel like you have a really strong sense of architecture and buildings. Is that something that interests you? Obviously for this book it was important, but in a general sense is it important?

It always has ... When I try to think of where it started … when I was about 14, and I would visit Cape Cod, one day I decided to draw the front view of all the houses on the street where I was and then walk up to the front door and say “Look, I just drew your house, it’s $10.” [laughter] That’s where it starts for me. But why? God, who knows.

I like specificity, which is of course the key to storytelling. The more generalized you are, the less interesting, the less involving. The more specific, the better. The most specific the better. More detail, the better. So when I draw stuff, I like to use reference material and draw things as they really look now or looked at the time when the piece takes place. And I’ve always liked that. I used to collect postcards and I still use them for reference – I don’t collect them anymore but I have thousands and thousands of postcards, mostly buildings and main streets and amusement parks. And I refer to them quite often.

Getting back to the themes of the book, you touched early on about the idea of a lost opportunity. And I feel like if there’s a really overarching theme to the book, it’s that. I think it’s why the character of your Uncle Al is such an important character in this book and why you open and close with him. I feel like if there’s – I don’t want to say message, because this isn’t a message-y book – but if there’s an important theme, it’s “don’t lose touch. Know your parents. Ask questions. Find out who they are. Don’t lose touch with that connection you have to the past.” You even talk early on about one of your ancestors, William Henry Jackson, who was the father of the American picture postcard. And there’s this central them that it’s important to know where you came from in a genealogical sense that this matters, and that if you lose touch with this, you’re losing something important.

And that your parents are real people. Roz Chast gave me a wonderful blurb on the back cover about we don’t see our parents as real people and that stops us from asking questions sometimes, it stops us from having discussions with them, especially when we’re younger. If we’re lucky and you live long enough and your parents live long enough sometimes that barrier comes down. But an effort has to be made, and it usually has to be made by the child, not the parent.

I didn’t do that. Luckily, my mother left me all that material, because otherwise this book never would have happened. And yes, the book is sandwiched between two visits to my uncle. When I first visit him in effect the book is born out of that visit and then the book goes through the whole story of the relationship, and who Lariar is and how he affected me and my father, etc.

And then at the end, I was actually thinking as the book was winding down I was thinking “How am I going to end this? There are so many ways to end this. Which is the right one?” And the phone rings. And my uncle says my aunt died. Nell died, her name was Nell. And I said well I’ll be down there for the funeral, when is it? And I went down for the funeral, and that was the end of my book. I had that trip to sandwich from the first trip to the end of the book I had those two things. They weren’t devices because I didn’t do it as a writer, it just happened that way.

And when I went down to visit my uncle, last year whenever it was, after the funeral we had another long talk and I’m in the room – he’s a ham radio operator, this guy still has a ham radio with all the tubes. It’s like going into the 1950s to walk into his little ham radio room. This is a guy who was a draftsman for Western Electric. He drew the electrical systems for the Nike missile. And when I asked him about that I said, “What do you mean, did you create it? Or did you just do what someone told you?” He said, “No, I had to figure it out.” This is before printed circuits, so everything had to be boxes and wires. This is a guy that’s … he also left me all of his drafting supplies by the way on that trip, which is wonderful.

We’re in the room with this ham radio and I had been there before but I had never been sitting where I sat, and I looked up in the closet behind him and there’s all these boxes of letters that looked very old. I said “What are those Al?” He said, “I don’t know, my father left them to me. I never opened them.” “Do you mind if I take a look?” And there’s three big, big boxes of thousands of letters. One box is entirely letters that he wrote to his parents and that his parents wrote to him during World War II when he was overseas. He was totally shocked, he had never seen them before. Another box was all of his father’s attempts to exploit William Henry Jackson’s name [laughter]. TV deals, movie deals, book deals, he was constantly trying to exploit his father’s name.

That was fun and interesting, but the third box there’s letters from my mother and my father to him, before they were married and when they were just married. And my father was a completely different person. I was reading these letters, he was this optimistic, happy guy. And I thought, "Well, the picture I’ve given in the book of my father is not full, it’s not a full picture. Here’s the rest of it." And so that’s how the book ends.

The book really is the story of a marriage. I don’t think of it really as the story of an affair. That’s the structure of it, but it’s also the story of a marriage, and a very complicated and in many ways unhappy marriage. But when I found these letters in my last visit, it was like a full circle feeling. I felt like I had done more justice to my father by using them in the book.

Next year is going to be Zippy’s 30th year of daily syndication. That’s quite an achievement. Has your approach to the strip changed over the years?

Oh yeah. It’s not a conscious thing on my part but I feel like every five or seven years I kind of reinvent the strip. And it doesn’t happen consciously. I don’t say, “Time to reinvent the strip!”

In the year 2007 – I’m about due for another one – I suddenly thought, “What if there was a town in which all the people were like Zippy? What would that do to various story lines and would it open up the strip? Yeah I think it would." So I created Dingburg. Dingburg, of course, with a nod to Duckburg, Scrooge and Donald. I’m winding that down now.

I don’t quite know what the next step is going to be. But every so often I feel like I just breathe some new life into it so that I’m interested and not repeating myself. And I hope that I can do that again. It could be soon. I don’t see myself stopping anytime soon, but of course I’m not getting any younger.

Tell me a little bit about the project you’re working on now.

When I finished my book, I took a break obviously, a breather. But in a couple of months I missed doing the book, I missed that feeling of doing a long narrative. So I thought, “Is there another book?”

I took another month, many walks in the morning and it came to me that I should do the biography of Schlitzie the pinhead, who is the major inspiration for Zippy. If you’ve seen the 1932 Tod Browing movie Freaks you’ve seen Schlitzie, he has one scene in that movie where it’s hard to hear what he’s saying.

I started researching Schlitzie. I found two people who knew him well. [One was] his last manager. He worked in circus sideshows right up until a year before he died in 1971. And I found a man who had spent an entire summer with him in Toronto in a circus, living next door to him and kind of taking care of him.

I got wonderful stories. The idea is to make Schlitzie the pinhead be a human being, not a sideshow freak but to try to bring him to life as a human. I’m about 25 pages into it and it’ll keep going. It’s loads of material and I’m very grateful to have two really wonderful direct sources to use for anecdotes. It’s through detail that things come to life. You can research something all you want but if you don’t have those moments when something comes alive, then your story can be very dull and I’m trying to make Schlitzie into a real person.

We don’t have much time but I think we can get one or two questions in.

Audience Member: What is the title of your mother’s novel and second, as you’re looking through Lariar’s archive, was there any flicker of reference to your mother or an influence from her?

Her novel is called Departed Acts. And it’s a line taken from an Emily Dickinson poem, which is reproduced in the book.

Did I find any mention of my mother in Lariar’s papers? It’s also in the book, that’s a guess. There’s one photograph of him with a big lipstick kiss on it. Lariar was married, he had two children. I haven’t heard from them yet by the way. [laughter] Any day now. [laughter] One of them is on Facebook. I’m not reaching out.

Mautner: You’re not going to friend him any time soon?

No, no. [laughter] Who knows what they knew. But no, the only connection from his papers is what I surmised to be maybe my mother’s lipstick kiss on a photograph.

Audience Member: You’ve often commented on the difference between high and low art. Has doing long-form graphic novel changed your thinking about that or deepened it? Altered it in any way?

The high art/low art distinction to me is irrelevant. I recognize it and I see it all over the place, but the kind of comics we’re doing – people in this room and at SPX – are eroding the idea that there’s this line between comics and painting or comics and graphic novels and real novels. That line is getting broken and blurred and I think that’s all to the good, because why make a distinction? It’s all art.

Audience Member: Question about fiction and nonfiction. I’m really excited to see you doing longer stories again, but I’m surprised that there are these nonfiction, research-heavy projects when that’s not what I think of with your older work. Is that new for you? Do you find it interesting? Do you think you’d do long fiction too?

I enjoy research. I didn’t really think of the book as nonfiction. I thought of it just as a story that I had to do. I didn’t say to myself “This is nonfiction, it’s not fiction.” And of course when I read my mother’s novel, that was fiction. So fiction got into it in that way. And the Schlitzie book is going to be nonfiction too, I guess but you have the right as an artist, as a cartoonist, to invent scenes and events and people in a nonfiction structure that in effect are fictionalized. That’s allowable. I think mixing the both is actually a pretty good idea.