Kate Beaton is a member of that rarest of rare breeds: a financially solvent cartoonist.

OK, I'm kidding (a bit). While the difficulties of making a sustainable living in comics are oft-repeated and the image of the poor, starving cartoonist has become cliche, it is certainly not unheard of to come across an artist who has been able to pay rent and groceries with their work.

Nevertheless, there are a few factors that make Beaton unique. For one thing, she was one of the first cartoonists to break out of the initial group of webcomics creators in the early Aughts. More to the point, she's not only managed to build a large and devoted following in a surprisingly short period of time, but it's a fan base that spans across several seemingly disparate groups. History fans, alt-comics fans, superhero folks, people who just plain "don't get comics" -- all of them like Kate Beaton.

That certainly seemed to be the case at the SPX this year, as a healthy line snaked around the hall to get a signed copy of Beaton's third Hark! A Vagrant collection, Step Aside, Pops, or perhaps her first ever children's book, The Princess and the Pony. Whatever the case, the show seemed like the perfect opportunity to sit her down for a lengthy interview.

The bulk of this interview took place Sunday morning at the Bethesda, Md., show, as we attempted to find a quiet place to talk (we unwittingly wandered into the "Tumblr brunch" initially). Sadly, we ran out of time (she had a signing, I had a lunch date) so the last few questions were handled via Google Docs.

Chris Mautner: I wanted to start by getting into your secret origin.

Kate Beaton: Can I preface this by saying I’m thoroughly sick of myself?

Mautner: (laughs) Well I’m going to make you sicker unfortunately.

Beaton: That’s OK.

Mautner: Tell me about where you grew up in Nova Scotia. What kind of a place is it?

Beaton: My hometown is called Mabou. It’s very small. It’s about 1,200 people maybe. If you read Wikipedia it’s all over the place. So to give you a sense of the size, there were 23 people in my grade from primary to 12 and I went to a primary-to-12 school. I was the one who could draw. That was my super power. There was one who was good at hockey and one that was good at math and I was good at drawing.

Mautner: That can be great and awful at the same time to know everybody the whole way through to 12th grade.

Beaton: Yeah, they’re like 23 brothers and sisters almost, because you literally grew up with them and saw them all the time.

Mautner: But if you’re known as the odd kid or the strange one …

Beaton: Yeah, that was the only thing. There were people who were odd and strange and I felt like in a bigger school they’d have a group of friends. Instead they were just outcast types. I was nothing in particular. (laughs) I was friends with everyone but not best friends with anybody in some ways. Although I had friends I wouldn’t have counted myself among a popular group or unpopular group. I just did my own thing. And I was the one who could draw. And if there was a prom or whatever, I made the decorations.

Mautner: Were you always drawing, even at an early age?

Beaton: Yeah. I remember early on, grade two or something, I was like, “I can draw.” And because it’s such a small place, there’s limited opportunity but there’s an immense, tight-knit community there. I go back generations in that town, probably to the late 1700s. There’s a real sense of place and identity that’s rooted in there. People know who you are, who your family is and when you have a talent, they’re all rooting for you.

Mautner: Do you look back and feel like that time, having that community, grounded you in a way and helped you?

Beaton: I’d say so. It’s not like I was famous in the town for cartooning.

Mautner: No, but after the fact –

Beaton: They’re very proud. They’re immensely proud and I’m always immensely touched when I go home. They sell my books in the post office, because there’s no store. My mom has to supply the post office with books. She gets them off of Amazon. When you’re from a place like that, when you’ve got a CD – there’s a lot of musicians there, they’re all fiddle players – but when you put out a CD, people go to your parents’ [house] to get it. (laughs) They started going to my mom, so she put them in the post office so people could get them there.

Mautner: What did your parents do for a living when you were growing up?

Beaton: My mom worked in a bank, and my dad is a butcher at the store.

Mautner: Were they supportive of your interest in the arts?

Beaton: Very. And my mom tried really hard to give me opportunities because there was nothing there really. We didn’t even have art classes. She made an effort to put me in things like 4H, so there would be like painting classes or whatever art-related stuff, [she would] make sure that I got into those. And she used to set me up with anyone that did local art, talk to them and show them my work. There was one painter in my town, Peter Rankin. He’s a fisherman but he’s a self-taught painter. His paintings are really good. He taught kids art lessons when I was really young. He always checked in with me, like “How’s that art coming?” You know the way that small towns can be. And I always felt very supported in that.

But at the same time, because it’s this rural place with not a lot of opportunities, and the Nova Scotia economy is a terrible time all the time, there wasn’t – if I said, “I want to be an artist,” a lot of people would have been like, “Are you sure? Being a nurse is much safer, being a teacher." They believe in your talent, but ...

Mautner: They don’t see it as a career.

Beaton: Maybe. If something happened, and the way it did was serendipity almost – they’re like “that’s amazing.” But when I was a teenager and wanted to make art for a living, they were worried because it’s a risk. People make fairly safe moves there, which is what happens when you’re in an economically disadvantaged place. Risks are for privileged people with money to fall on their face if it doesn’t work out.

Mautner: Were you aware of that at the time people were saying those things to you?

Beaton: It’s kind of born into [you], a carefulness about life. You grow up in Cape Breton and you have to leave. If you want to make a good living you have to leave. And then there’s an immense sense of loss over generations as well – this weird, insanely ingrained sense of identity and place, and then you have to go to make a living. There’s all kinds of songs about how much people miss home and how they had to go. But there’s an emphasis on doing better for yourself. And having a good job with good money and be able to raise your family and not struggle as hard as the last generation did. That’s what every generation wants.

Mautner: Were you exposed to comics at that age, even newspaper comic strips?

Beaton: We had a newspaper. It was basically newspaper comics and Archie comics and randomly some weird graphic novel interpretation of some saints lives that were around. Basically whatever you got your hands on worked. The library was small and any book that would come your way you were like, “Holy shit!” (laughs). It’s not like you had your choice. Anything that came along you’re like, “Wow”. I have these weird books ingrained in my memory, not because they were better than other books but because they were the only ones that showed up. There’s a whole comic about Saint Marguerite Bourgeoys, the French-Canadian saint. She was a nun. I read it, I was like, “This is amazing.” (laughter)

Mautner: At the time you were reading these was there anything going on in your head like, “I wonder who does this,” or “I wonder if this is a job”?

Beaton: A bit. You’d get the book orders at school and you could order the collections, so I had all of Bill Amed’s Foxtrot. I pick a comic, that’s my comic. I like the way it was drawn, I used to try and draw the characters, you know, we all did that stuff. I still have box of those under my bed at home.

Mautner: Yeah, my kids are huge fans of Foxtrot.

Beaton: Yeah, it’s a good comic. It’s funny. I got into it in grade five or six, I loved it. In the school library there were these super-old Peanuts collections. And you realize, "Oh the drawings change!" I remember looking at the older Peanuts and being kind of blown away. There [were] these ratty old books in the library, and I like the older drawings better. They’re very charming, those early Peanuts.

Mautner: It strikes me in your work that’s one of the large influences, 'cause your work has that comic strip rhythm of set up, beat, punchline. I assume that was something influential on you at an early age. You weren’t reading superhero Secret Wars or Love and Rockets or anything else.

Beaton: We had Archie too.

Mautner: Even Archie has a setup, beat, punchline delivery method.

Beaton: I guess so. The reason I got into gag comics is because the first [comic] I made was for my school newspaper [at] the university. No one else was serializing anything, it was all just, “Bleh, there it is.”

Mautner: And if even if you wanted to get into comics, you probably didn’t know how to go about doing that.

Beaton: No idea, no. There was nobody else who drew. There was one kid in my class who also drew comics. In grade six we used to draw comics to trade with each other. They were just about the teachers and stuff, they were really stupid. But then you become a teenager and there’s a lot of kids who like to draw and then it falls off and they’re like, “I’m cool now.” (laugher) And they go fuck off and be cool. And I was like, “I still like to draw,” so I just went off and did it by myself.

Mautner: But when you went to university, you went to study history, not comics.

Beaton: Yeah.

Mautner: So I’m assuming that in addition to comics you were a pretty avid reader growing up.

Beaton: Yeah.

Mautner: So history was always there as a definitive interest in addition to art.

Beaton: And again a lot of that has to do with the place being very invested in its own culture. They’re very aware of a lineage and a shared history with the community.

Mautner: Was that what attracted you to studying history?

Beaton: Sure. We took Gaelic in class. Language and local cultural studies, that kind of thing. When I was growing up there was a huge movement to reclaim a culture that was being lost by modernization. Now the focus is on the kids – kids have to learn to dance and fiddle and sing in Gaelic and do all this other stuff, so I was in the Gaelic choir. ... [It's] this older generation sort of cradling up this younger one to give a shit. And it worked, for me. I was like, “I’m all about this. I love this” And so it seemed kind of natural to have an interest in history.

Mautner: There’s something about it that obviously stuck with you. Was there something about learning history – was it the stories themselves or just the sweep of it for you?

Beaton: Oh yeah, absolutely.

Mautner: Because it’s one thing to have an appreciation for your culture or an interest in history, and I think it’s another to want to study it in a university and going forward in your own comics, make it the centerpoint of what you’re doing.

Beaton: I don’t know, it’s hard to say why you have an interest in anything in particular. ... Whenever a documentary was on, because you only had two channels, it was that thing where, “I’ll get whatever I can get”. I remember ... do you know The War Amps?

Mautner: The War Amps?

Beaton: The War Amps. They’re like a war amputee society. A lot of them are old men because a lot of them are WWII vets. And they had a commercial on TV that was like, “Write to us if you want to see our documentary.” (laughs) And I wrote to them and got a VHS in the mail. We had to mail it back after we watched it. That kind of thing. I was like ,“Oh boy, I want to see that. War Amps documentary.” (laughter)

Mautner: Why haven’t you done a strip about that?

Beaton: I don’t know! Whenever you saw them on TV they were these really adorable old men, missing a leg or something: “I was at this battle and then I stepped on a mine.” It’s a lot of “never again” sort of thing. And they do work with kids. They receive a lot of funding and support. They’re really cool guys.

Mautner: OK, transitioning from there … I know you’ve told this story before, but you were doing these comics in your college newspaper. How did that transition to putting them up on the Internet?

Beaton: I finally had an outlet for this kind of thing when I went to university and there was a newspaper you could submit to. And our student newspaper was independently owned. I think it’s one of the only ones in North America or in Canada that’s an independently-owned student newspaper. So you could put anything you wanted in there. And I did. And I got good attention for it. I knew that it was everybody’s favorite part of the paper. I knew that everybody read the comics section. I knew that if people found out that I was the one behind this one comic or the humor column they would get excited, that’s a rush when you’ve spent your whole life drawing without anybody really paying attention.

Mautner: What were those early comics like?

Beaton: All the early strips were campus life type of things or something that was happening in the news recently or the cycle of campus life, like we’re all going home for Thanksgiving now and now it’s Christmas vacation. I read them and I’m like, “These are so bad,” and they are. Right at the end, right in my fourth year, I started to hit, when I wrote the humor column, which I was better known for than the comic –

Mautner: Oh, you had a humor column, too?

Beaton: Yeah. It was called “Super Quiz.” [Mautner laughs] And I replicated it on the Hark! A Vagrant site.

Mautner: Oh yeah, I remember those.

Beaton: Yeah, they’re ten questions with fake answers. It was a fun puzzle to put together, because sometimes the fake answers would relate to each other and be a joke within a joke. Anyway, I started to make comics and write the quiz in ways that resembled Hark! A Vagrant. They were about history and I could be clever and I wanted that smart humor instead of that crass humor.

It took a little while to figure it out. And it’s only at the end of the university career that you see it. There’s one or two comics that look like what I do now and one or two quizzes that pull in on that. I was really proud of them. I felt like I was starting something. When I graduated, and I had nothing. [laughs] No more audience, everyone was gone. But the year that I graduated university was the year that Facebook was founded, 2005. All through university we didn’t have Facebook. People had some MySpace stuff. But I didn’t even really have a MySpace. And I didn’t have a LiveJournal. Early on Facebook was different than it is now. It’s kind of hard to remember, but when it started, it was only college kids or people who would make connections with each other in a genuine way instead of the way ...

Mautner: ... we do now.

Beaton: ... with, "Like this fan page” and stuff. If someone made a [Facebook] group of cartoonists in this one city, you could join it. And it would be people of a certain type, not just anybody but this young crowd of talented people, and you were more guaranteed to hit on something.

Anyway, all of my friends were joining [Facebook] and I was like, "That’s my audience, my friends from university!” So I just made Facebook albums of comics. And those early ones were about my friends, because as soon as you start making comics, people are like, “Make one about me!” [laughter] And you want to please your crowd, so you’re like, “Sure.” So you make one about them and no one else gets it.

People were enjoying them and I met two people that were pretty key when I moved to Victoria BC, to work at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia.

Mautner: What were you doing at the museum?

Beaton: I was everybody’s assistant. Because it was a small staffed museum. I still miss it. And you know what, it is in dire straits right now.

Mautner: Oh no.

Beaton: Yeah, they were planning to move out of their building for a long time and they finally got a place on the waterfront. So they have to move out of their old building, but then the deal for the new building fell through and they’re homeless. It’s just weird and sad, and it’s a place that’s very dear to me, so I hope they figure it out.

Mautner: So at the time you were making these comics for fun, but you were thinking about what you were going to be doing with your history degree, right?

Beaton: Yeah!

Mautner: And what were you looking at doing? Becoming a curator? What were your long-term goals?

Beaton: I wanted to either keep on with the museum stuff 'cause I loved it, or I was going to take an M.A. in labor history at Memorial University in Newfoundland. That was the plan. And then become a professor. I talked to some of my old professors about it, but I had to pay off my student loan, that’s why I went to work [a mining site] at Fort McMurray and it just so happened that the comics took off while I was paying off the loan and it became another option that I pursued, because it was open.

Mautner: When you say took off, can you describe what you meant?

Beaton: Well, when I was working for the museum, I had these comics on Facebook and people were making those Facebook groups. I was added to a group, Cartoonists in Vancouver. I wasn’t even living in Vancouver, but I looked at the names, and there was one other person on the list who was in Victoria as well, Ryan Pequin. I looked at his work and was like, “This guy’s awesome." His comics are funny – he was doing journal comics then. So I wrote to him – or he wrote to me I forget which – and I was like, “I like your comics,” and he was like “I like your comics,” and we became friends that way.

And, at the Maritime Museum, where I was an admin. assistant, the programs manager happened by chance to be Emily Horne, who is one half of "A Softer World," which was a comic that started in an alt-weekly in Halifax and was then put online. So she had a webcomic, and Ryan Pequin had a LiveJournal. And she was like, “You should make a website,” and Ryan was like “You should make a LiveJournal cause that’s where all these cartoonists are.” And I was like, “Ohhh.”

Mautner: So at the time you’re finding a community of like-minded people who are making comics and finding [the chance to pursue comics] as a serious recreational pursuit if not a career.

Beaton: Yeah. Cause even when I was at the university making comics for the school paper, it was a real continuation of my small town, where I was the one who drew in my small town and then I went to school and I was the one who made the comics. It wasn’t that nobody else made comics, people did. But I was the … chairperson of comics or whatever. There was no community. There was just people randomly submitting, and I didn’t know any of them. And then to be introduced into this LiveJournal community, where there were people who did what I did and I liked their work and they liked mine, I had never had anything like that before. It was amazing. This was 2007. I was blown away by that. The fact that there were other people like me. ... But I was late to the game.

Mautner: Were you?

Beaton: Well I was 22 then and I didn’t grow up reading comics. I didn’t go to art school, all this stuff. I just showed up when I showed up. But then … I’ve told this to a lot of people, but I believe it’s true: 2006 to 2008, that was a good time to get into webcomics because there were only a few people with a website doing it. People were reading it, so you could make a name for yourself without having to be amazing. You just had to be alright. People would read your comics. And I was all right. I started Hark! A Vagrant, I made the website (and it was an awful website) in September 2007. I started making living off of comics in September 2008.

Mautner: And what was that based off of, advertising?

Beaton: Yeah, and as I got linked up with Jeff Rowland from Topatoco, and he sold shirts and stuff. Early on in webcomics everyone made a living off of it by printing off their own shirts and shipping them to their house. And it was a lot of work. It’s a lot of work to do that by yourself and make a comic. So Jeff Rowland started Topataco, which basically takes that work off of everyone’s hands for a cut. And so now all of the merchandise goes through the store. If he didn’t have that I wouldn’t have done it cause I don’t know anything about that stuff. I wasn’t one of those people who was like, “I’ll make this happen hell or high water.” I was going to work in a museum. But the opportunity to give it a shot with it rolled up in your lap, you’re like, “Well, I’ll try this.”

Mautner: At what point did you say, "This is what I’m going to pursue full time, I’m going to make an effort to become a cartoonist?"

Beaton: I started the website and then I had to leave the museum because they could only give me $13 an hour and 21 hours a week, and I was working as a maid on the side. So the time line here is: I graduated in 2005, I went to Fort McMurray for a year. And then I left Fort McMurray and I went to Victoria for a year. But my student loan hadn’t been paid off so I had to go back to Fort McMurray for another year. The comics took off in my second year at Fort McMurray, after I had left the museum. I was working in the oil sands. And every day was crappy. But then I would come home to my bunk and I was using the workplace computer/scanner thing to put my comics online, and I was drawing them on computer paper. I would come home and talk to my LiveJournal friends and I understood as time went forward that I was gathering an audience – not because I knew anything about website stats, because I still don’t get Google. I have no idea who reads my comics. You get mail. And the Jeff Rowland said we’ll do a test with these two shirts, we’ll put them up.

Mautner: Which ones were they?

Beaton: They were the stick men ones. They were two stick men shirts that I drew in MS Paint. But they were funny. And one print of a comic that took off, Tesla. And so I had t-shirts and one print for sale on the Topatoco site, and they sold I don’t remember the numbers but it was clear that if I wanted to give it a shot, I could. And that’s when it became real. I paid my loan off, I saved $10,000 – I worked for a few more months and saved that much – and I went to Toronto and lived with Emily Horne. (She had moved from Victoria to Toronto at that point too.)

Mautner: And Toronto, of course, has a big cartooning scene.

Beaton: It does, yes. And so I met Ryan North, who has been immensely helpful. If my website breaks or I have any problems, I just call Ryan crying, and he’s super cheerful. That’s the thing, everybody has been … left to my own devices, I’m a careful person. I’m not the one who’s going to say, “I’ll take a risk and live on a dream,” because I didn’t go to art school. I’m not that type. Even though it was the thing I loved the most I was like, “Well, but I also need to make a living.” And I didn’t try to make it in comics until I had paid off my student loan and saved a pile of money, to make sure I wouldn’t starve. (laughs)

Mautner: Well, that’s the issue with comics isn’t it, balancing being able to do what you love – and with you of course you’ve got a comic that combines a lot of your interests –

Beaton: And at the time nobody really knew where webcomics were gonna go. There was still a weird pushback from the print industries about how legitimate they were. Which I never paid attention to because I didn’t give a shit about comics.

Mautner: I wanted to ask you: As you were getting into this community, were you trying to find out more about other comics, about other cartoonists around you and the industry gossip as it were? 'Cause I could very easily see you [saying], “That doesn’t concern me.”

Beaton: I thought it was all super-interesting. It was like a door opened to a magical world that you had never heard of before. You were just the one person who drew and then you were the one person who made comics, and then you went to the north of Canada (laughs) to work on a mine, and then you’re a famous cartoonist! And that’s basically what [happened]. So it was all super-fascinating to me and the things that people were angry about I was interested in reading about. But none of that ever felt like it applied to me because I always felt like I was outside of the comics industry. I still do. I wanted to learn about it because I’m a natural learner. That’s why you study history, you just absorb all the information that you can. But I remember … you learn about something like the old message boards on the Comics Journal (laughter).

Mautner: Oh my.

Beaton: I know! And I remember before they shut those down I read a few threads and they were just like people yelling about stuff and I was like, “Why are they so mad? I don’t understand.”

When I came in it was “Print vs. Web! Who’s cool and who’s legit and who’s not or who deserves what." I never had invested in any part of comics culture at all. So it was like coming in and looking into the glass window and seeing all this kerfuffle that I just watched it with interest. I didn’t identify with either side.

Mautner: I can see you looking at it and saying, “Who needs that?”

Beaton: Basically. I’m not going to come out and be like “Team Webcomics!” This is how it worked out for me, I’m going to keep doing it.

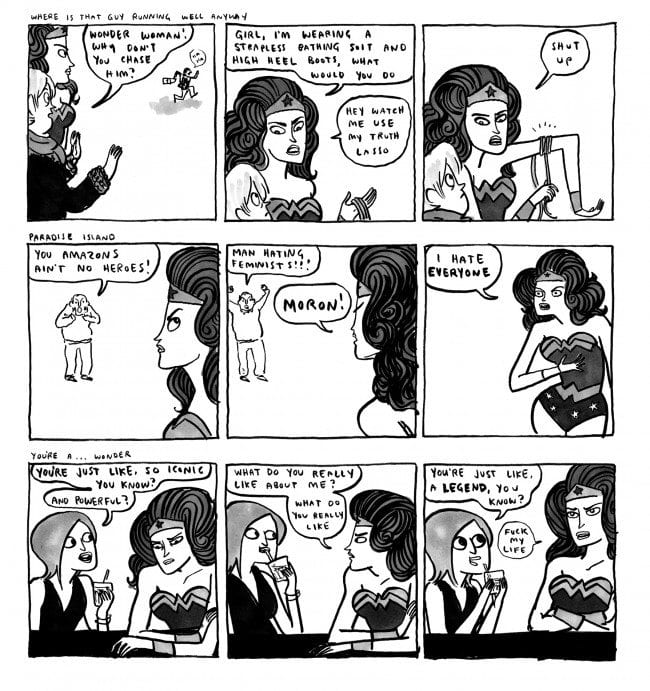

Mautner: One thing I find interesting about your success is ... we still live in a comics culture of these little circles. You see it here at SPX, where you have the webcomics people over here and the Fantagraphics people over here. You have an audience that really crosses borders. Superhero fans like your comics. People who don’t like comics like your comics. (Beaton laughs) Were you aware of that early on? What do you think it is about Hark! a Vagrant that it's able to broach barriers that other people for whatever reason aren’t able to?

Beaton: I don’t know. I think some of it has to do with a lack of investment in any of that stuff for sure. And the fact that my various weird forms of isolation from comics and from everything kind of solidified my voice in a very distinct way. 'Cause I wasn’t pulling influences from the same places other people were. And maybe that stuck out, but it’s hard to say.

We’re at SPX right now and SPX was my first real comics show where I showed up with something to sell. And it was just photocopies of a book. And it was sideways! It was badly made. Some people make comics and they make these beautiful minis. It was like, “How the fuck do you staple all these pages together?” I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.

And then I showed up here because again on the kindness of others. Phil McAndrew had a table, and I knew him from LiveJournal. He’s my pal, and he’s like, “just do an art table, it’s cool.” You know, the way they do. And it’s such an awesome, inclusive thing. So I was with Phil and Emily and Jess Fink was there.

Mautner: I think I remember that show.

Beaton: Yeah, and the line up for me went around the table and … I had no idea what to make of it. I was embarrassed. It was blocking other people’s tables. I felt like such a fraud, because there were these established cartoonists and ... I don’t even know. I came here for fun. I thought it was going to be more “LiveJournal pals,” just hanging out, but instead I had this insane line. I was shocked and I wanted to be happy for myself. Instead, I went back to my hotel room and cried by myself (laughs). It was weird.

Mautner: Well, you’ve experienced a kind of success that’s not really comparable. You’ve been interviewed [recently] by PBS, etc. so you’ve achieved something – I don’t want to say without trying hard because you try very hard – but more inadvertently –

Beaton: Yeah, I’ve never advertised or anything like that. I’ve always felt like there was something … I don’t even sign my comic! (laughter) I tried very hard all through growing up in ways that didn’t translate into anything. There would be small things doing what you could with what you had. There was a gift store in the town next to ours and I asked mom if she could take me to the guy who ran it. I was like, “I can draw pictures and you could sell them.” (laughs)

Mautner: It sounds like coming face to face with your audience had a very emotional impact on you. Was it hard for you to process that success?

Beaton: Yeah, from the beginning. I remember people telling me early on before comics was my job, “Man, you’re famous.” And I was working in [the oil sands] in northern Alberta. I couldn’t parse it. Say you got 100 fan mails because of your webcomic. And this is a time when people are like, “What are webcomics?” Nobody knew if they were even legitimate. If you made them you felt that they were, but you still received pushback. I remember there was a lot of articles like “Webcomics have arrived! Finally, they’re a real art form now and they weren’t before.” A lot of weird shit like that around. It was hard to make sense of your position in the world and your position in the world of comics, just because you had a lot of web site readers, that doesn’t mean that you’re a good cartoonist.

I don’t know. I still don’t really understand it. Although I have worked hard to build a relationship with an audience because I want to be a real person to them. I think that makes a difference to … it’s a whole learning process. You don’t know who any of these people are.

Mautner: And they’re coming to you with stars in their eyes, which can seem disconcerting.

Beaton: Maybe. I don’t really deal with sexist stuff any more. Early on you invite that kind of thing because you’re a young woman making a comic –

Mautner: Well I was going to broach the issue where you made the request to have people stop saying things like “I want to have your children.”

Beaton: I regret that, not because ... this was years ago but I read a review of a work by a friend of mine and in the review the guy writing it made a comment about how she looked. That just invited the comments section to post pictures of her and say “I’d hit that.” Or “I wouldn’t”. It was so disappointing. If he had just left that [comment] out then maybe they would all talk about the work. And so that upset me that day and I was like, "Arrgh, that sucks.” I wanted to say something about it but I didn’t want it to be too specific because if you’re too specific people will go, “Well I never said that one thing.” So, fine. I tried to make a broad statement. I chose the babies one, “have your babies.” But it is a benign statement. Nobody says it and I don’t care if people say it to me and I don’t care if I ever hear it. So it was a bad example. But then everyone latched on to that one example and the broader message was lost, as usual.

I really had to learn how to say exactly what I mean when you want to talk about something like that. Leave no holes and think about it. Don’t just shoot off. That was like one second of thought and I was like, “Blargh, there it is.” And there are people that still hate me because of that one tweet. I don’t get that but I don’t care. They can hate me if they want to. Whatever. But I have learned to curate what I say to be exact. Because Twitter is such a throwaway medium, it’s very easy for people to be like “blah” and let loose on something. But then that never goes away. You have to realize that everything you say stays forever on the Internet. Nothing ever dies. We enjoy a certain anonymity and easygoingness, especially when we’re younger–

Mautner: You don’t think about what you’re saying. It’s something I work with my kids on all the time and even though in some ways they’re more Internet-savvy than I am, I don’t feel like they get it.

Beaton: Exactly. It’s a process you have to learn. I don’t want to not talk about things that I care about but you do have to learn to say exactly what you mean.

Mautner: Do you feel like you’ve gotten to that point?

Beaton: Yeah. I think I do all right. I don’t start any flame wars (laughs).

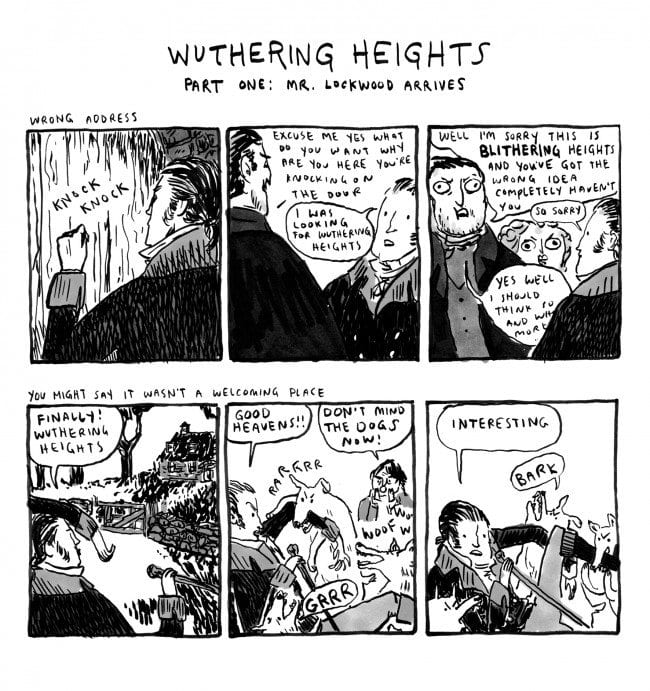

Mautner: With Hark! A Vagrant, I think there are two reasons why it’s as popular. One, you’ve adopted this comic strip format – get in, get out, you can read it quickly, it’s not part of a huge epic storyline (as good as those are). Second, you’re educating and rewarding readers who might be into Austen or Dickens or history. That’s how my wife got into your comics, because she’s such a Dickens fan. I think it rewards people's interest in the arts and history.

Beaton: It does, yeah.

Mautner: When you’re doing Hark! a Vagrant, are you conscious of an attempt to educate as well as entertain? Like, “No one knows about Ida B. Wells, I have to do a strip about her.”

Beaton: Yeah. It’s all of those things. And I choose the gag format honestly because I am most impressed by well-crafted humor. I don’t like presenting something that isn’t finished. I don’t like leaving things hanging, I don’t want a story with its ass hanging out. I want it to all be there and to have crafted this thing. My favorite humorist is Stephen Leacock and when you read his parody novels, they’re only a few pages long and they’re just perfect. You can’t just go on and on. A lot of humor books and things, they’re comedies and they try to go too long? You get tired of it. You’re like “that movie needed to be shorter.” You don’t see too many novels like that.

Mautner: It’s like the half-hour show or cartoon show that they make into a film and it’s just too long.

Beaton: Exactly! So that’s what I really believe with humor. Books ... where the chapters are very short, but it’s very smart. That’s the kind of thing that I’m drawn to. It’s not because I grew up with newspaper comics. It’s because I admire humor writing. And the best humor writing and the best humor presentations are usually quite short. Because you perfect this little gem.

Mautner: It must take a bit of trying to get it right then. Because sometimes you’re coming to the audience with characters they don’t know. So you have to tell their story as well as hone that wit.

Beaton: Yes you do, because my audience is people who have never heard of this, people who have and people who have written their dissertation on it. It’s all over the map and you’re aware of that. That’s why my comics started out as six-panel gags and stretched out into six strips. So that in the beginning you get to know the character a little bit, and then by the end you feel that you know them when I’m making a more esoteric joke. Or something like that. There’s a formula to it, definitely.

Mautner: How hard is it? How many revisions –

Beaton: Lots. I rewrite a lot. Writing is a long time and it might just end up being this stupid fart joke in the end but –

Mautner: – but those are the best.

Beaton: Yeah. I like going back and forth between the stuff that is just silly nonsense and the stuff that is a bit more book heavy. Because if you do one or the other all the time I think you’d get tired of it and people would get tired of seeing it. I like throwing in different stuff. 'Cause we all have a broad taste like that. We like to laugh, we like to learn, we like to look at something silly and we like to think about things a bit more sometimes. I just go with whatever I feel is going to be the best thing that I can make at that time.

But your question about the history stuff –

Mautner: Well, I was kind of leading into a question about your process. You were saying there’s a lot of rewriting involved. Do you weigh more towards the writing with the art coming more naturally to you?

Beaton: Yeah, a lot of times I finish writing the comic I think, “Ah, job done,” and then I think, “oh fuck, I have to draw this.” [laughter] Some people are like, “Her drawings look rushed.”

Mautner: I think that gives them a good quality.

Beaton: Absolutely. I always think my first pen stroke is the most intuitive to what I want to say so I’m always going for that early underdrawing which is happens to be my knack. Some people are amazing at composition, some people are amazing draftsmen, layouts and stuff. Mine is that I have a knack for gesture and expression.

Mautner: Yes.

Beaton: That’s my strength and I try to hone in on that more than anything else.

Mautner: I think it shows.

Beaton: Thanks. There are lots of times I’m like, “Oh I wish I went to art school and I wish that I knew how to draw a car.” My cars look like shit. At the same time, I’m very happy to be good at what I’m good at.

Mautner: That’s interesting , because it sounds like with the writing you’re really trying to hone it and with the art it’s more intuitive. It’s two different approaches melding together.

Beaton: I guess so, but when you’re writing comics, you’re writing the picture as well in your head. Like, when I write a script, I’m picturing the panel too. So it exists as a thing 'cause comics – people say there are two different skills, but it’s one skill. It’s writing and drawing together. One doesn’t exist without the other. When you have a comic where someone’s a good writer but they’re not a good drawer, you can tell.

And that’s another [reason why] I go for the gag comics as well, because it’s easy for me to contain all that in there.

Mautner: You mentioned that you felt burned out from comics while working on the material in Step Aside Pops. What do you think caused that feeling? How did you work through it? Do you still feel burned out or are you reinvigorated?

Beaton: I think it was just a natural burnout. Doing comics in a certain way, over and over, for some years. And then you lose a bit of the twinkle that comes with creating. Also, Hark! did well, and it was all over the place, and I felt all over the place, and I was sick of myself really. Sometimes you talk about your own work long enough, and you’re just over it. I worked through it by taking a break while on tour, and coming back and really changing up the comics. Experimenting more with form and content. I am always a little burnt out on comics, but I don’t know anyone who isn’t, you know? It is your job.

Mautner: Several of the strips in Step Aside break away from the traditional Hark! format. The “Nasty Boys” and “straw feminists” strips, for example, are lengthier stories and do away with panel borders entirely. Was this a conscious decision on your part or did this type of experimentation come organically?

Beaton: It wasn’t a conscious decision to say, I need to get rid of the panel borders and make these long things, I just wanted to make something different, and break out of the mold I had made for myself. This is what that was.

Mautner: We talked a little bit earlier about communities and how comics can still feel like it’s divided into all these little fiefdoms. Now that you’re established, and given what I said earlier about your work being able to draw in different types of readers, do you feel any affinity to a particular comics subset or enclave? Do you have a community that you rely on, similar to the group of webcomics friends you bonded with when starting out? Or do you try to ignore that sort of thing?

Beaton: I feel like I have friends in all the little pockets, and can sit at any table without necessarily having to be best friends with everyone at that table. Kind of like high school! But I rely on my oldest friends the most, which would be some of the webcomic crowd, the Toronto and New York indie crowd, and old studio mates. Most of us have expanded our frontiers beyond the thing we started with, so we are all criss-crossing each other’s paths.

Mautner: I was interested to learn that you had worked on Gravity Falls. How did you get involved in animation? Did you enjoy it? Is it something you want to do more of?

Beaton: All I did was help write some of the shorts that were made to air in between seasons! And the finished product was way different than anything I wrote, because in the end, Alex is the captain of that ship. I think he rewrites everything? I’m not sure. But that’s why it’s such a tight show, it’s a very singular vision, as well as a talented team effort. Yeah I’d love to write for TV again sometime.

Mautner: How did Princess and the Pony come about?

Beaton: At my book launch for Hark! in 2011, it was in New York, and these two Scholastic editors attended it. After the presentation and I was signing books, they came up to me and asked if I would ever be interested in doing a picture book. And I jumped at it, of course I would. The Princess and the Pony was among a few pitches I sent to them, and they said yes immediately.

Mautner: What was the biggest challenge for you in segueing to a younger audience?

Beaton: Figuring out how to write for kids is hard when you’re so experienced in writing for this other particular audience. Adults and kids are equally intelligent, but they have way different frames of reference. To get into that kids world, you have to try and tap into that. It’s always harder than it sounds.

Mautner: You’ve done color strips before (I’m thinking of the Darwin strip you did for Dark Horse), but Princess and the Pony seems in many ways your color debut. Was it enjoyable to not have to work in b&w anymore? (You mentioned you had to buy a Cintaq to do this book.)

Beaton: I don’t think I colored that Dark Horse strip! I colored a few illustrations and I colored some comics for First Second’s Nursery Rhymes book and a Marvel Strange Tales book. But yeah, the Scholastic book was my first real colored work. It was also a challenge, because I don’t trust myself with color, I don’t think I have a great sense of values etc. I got the Cintiq because I knew I’d get it wrong before I’d get it right, and that was true. I needed to be able to make mistakes and then fix them.

Mautner: Do you want to do more children’s books?

Beaton: I do want to! Kids are a great audience.

Mautner: What are you working on now?

Beaton: I’m not working on anything now officially, it’s the first time in years I don’t have a contract, but I’m also on book tour, which feels full-time. But I will possibly pursue a comic memoir of working in the oil sands.

Mautner: You’ve moved from an aspiring cartoonist to an established and successful author in a relatively short period of time. Has that journey been difficult for you? Do you feel like you’re in a place now where you can process that journey? Because success -- even if it’s not movie-star success -- can be daunting.

Beaton: I don’t think that I ever got used to it in some ways. And in some ways, it happened so fast that I don’t completely trust it - will it go just as fast? But then, it might just be my nature, I’m a worrier. I don’t feel like I have done the thing yet that solidifies my place in the world. Where I can take that breath and look back and think, “OK, you did it.” I’m happy for success but I’m not much good at reveling in it. There’s comics to make.