Taken at first glance, Marc Bell’s cartoon universe seems to be a persistently sunny, anthropomorphic place, a magical, happy-go-lucky world (or worlds) where everything from the food on your plate to the landscape is capable of coming to life and greeting you with a smile and a handshake. Bell’s comics are stuffed to the gills with adorable, oblong creatures that crowd his panels in the best Elderesque “chicken fat” manner.

But for all the visual liveliness and good humor, there’s a good deal of danger and malevolence present as well. It doesn’t take much, for example, for the cheerful little creatures to get stepped on, squashed or eaten, or for seemingly decent characters to run afoul of random calamities. Bell’s protagonists can seem just as easily plagued by anxiety as they can be blessed by a divine nonchalance.

Take Stroppy for example, the titular character in Bell’s latest graphic novel. Previously seen in Bell’s 2011 book, Pure Pajamas, where he was a quivering, insecure lad given to wearing elaborate costumes to convey a false sense of self-assuredness, Stroppy is now working a factory job, where he screws computer brains into the heads of little yellow creatures so they’ll be docile servants for his uber-rich boss Monsieur Moustache. (See what I mean?)

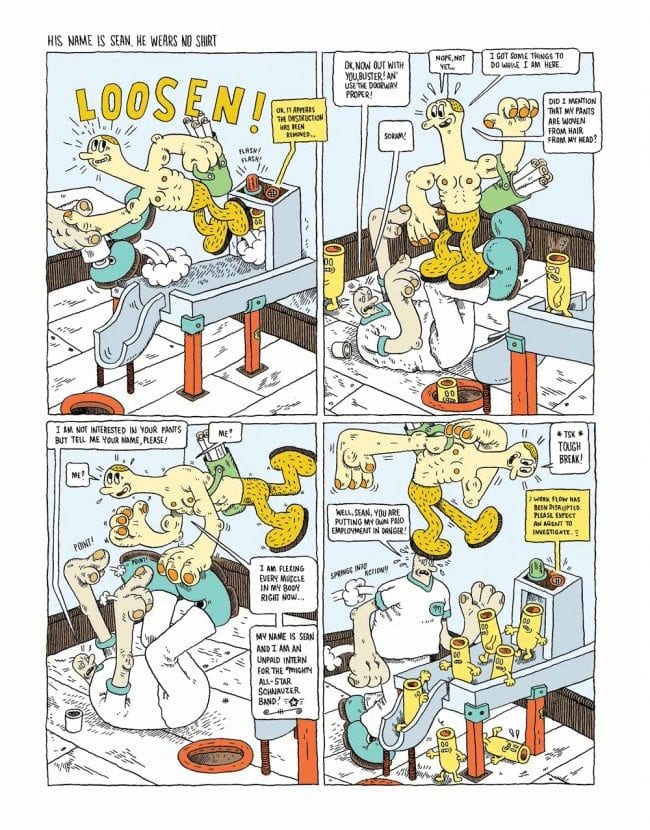

Through an inadvertent series of events, mostly due an oblivious and over-exuberant fan of the musical group/conglomerate known as The All-Star Schnauzer Band, Stroppy ends up losing his job and then his apartment. Wounded physically and emotionally, he enters a friend’s poem in a song contest in the hopes of obtaining the cash prize. When said friend is captured by the Schnauzers for his songwriting abilities, however, Stroppy must put ignore his wounds in order to perform a rescue mission (of sorts).

This is perhaps the most overtly political work Bell has done to date. Issues of class, inequity and injustice reverberate through the book, from the cruel, vain and clueless M. Mustache to the seemingly faceless and ruthless Schnauzer corporation, which steamrollers over the well-being of innocents with little regard for the consequences (fronted in large part by the aforementioned uber-fan Sean, a rather withering satire of the obsessive music type). While one should be wary of focusing too much on the political allusions, given the national headlines of the past year and a half, the sight of poor Stroppy cuffed and beaten by authority figures in the streets carries a contemporary resonance it would be foolish to ignore.

But lest you fear that a more straightforward narrative and ripped-from-the-headlines themes would mar Bell’s healthy taste for the surreal (and occasionally downright absurd) let me assure you that it has not been abandoned. Stroppy is filled to the brim with odd, off-kilter dialogue and jokes, impossibly elaborate machines and bizarre creatures that look more like layers of sediment than living beings. The highlight of the book (and the story’s climax) is Stroppy’s rescue attempt, which involves playing an elaborate miniature golf course designed to represent various Schnauzer Band songs. This lengthy sequence allows Bell to really showcase his layered, maze-like way with topography as Stroppy navigates a series of ornate singing structures that rival Dan Zettwoch’s feverish diagrams.

Disguises abound in Stroppy, especially among the ruling elite. Monsieur Moustache dons a variety of odd outfits and just about every single member of the Schnauzer clan turns out to have a secret hiding beneath their baroque exterior. Only by maneuvering around (and sometimes through) all this subterfuge can Stroppy – who seems to have cast aside his previous disguise – can find a way back to security and employment again. And if it doesn’t even out exactly to how it was before, and if some of those evil, rich folks haven’t had their comeuppance yet, that’s OK. Sometimes you get the goose. Sometimes the goose gets you.