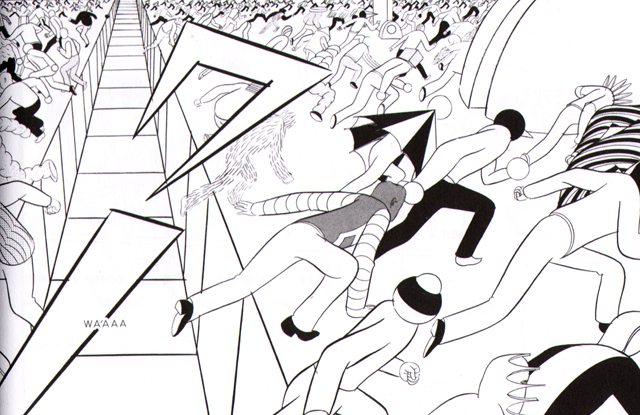

Seattle cartoonist Tom Van Deusen and I recently sat down and had a focused discussion about Garden, the 300-page comic book by Tokyo painter and manga artist Yuichi Yokoyama that was published in 2011 by PictureBox. The conversation helps reveal the way important new works get into a creator's mind and influence them in subtle ways. It would be hard to find two artists working in comics who are, on the surface, as dissimilar as Van Deusen and Yokoyama. And yet, as we talked, it became clear that Van Deusen, who is 29, was inspired and influenced by Garden, perhaps not in a direct way that will lead him to start moving groups of oddly dressed characters through fantastic environments -- but in the way that an intelligent and conscientious artist will develop their own style in relation to the major works of their time. (Note: in the excerpts from Garden below, read from left to right, top to bottom.)

Seattle cartoonist Tom Van Deusen and I recently sat down and had a focused discussion about Garden, the 300-page comic book by Tokyo painter and manga artist Yuichi Yokoyama that was published in 2011 by PictureBox. The conversation helps reveal the way important new works get into a creator's mind and influence them in subtle ways. It would be hard to find two artists working in comics who are, on the surface, as dissimilar as Van Deusen and Yokoyama. And yet, as we talked, it became clear that Van Deusen, who is 29, was inspired and influenced by Garden, perhaps not in a direct way that will lead him to start moving groups of oddly dressed characters through fantastic environments -- but in the way that an intelligent and conscientious artist will develop their own style in relation to the major works of their time. (Note: in the excerpts from Garden below, read from left to right, top to bottom.)

Paul: To start, I'd like to tell how this idea of discussing Garden with you came about. Tom, you and I are Facebook friends, and I posted a photo of one of my bookshelves. You made the comment: “Garden!” I was impressed that, out of all the great books on that shelf (Rube Goldberg,TinTin, Kliban, Tatsumi, etc.), you singled out the very one I would have mentioned if the situation were reversed. When I first read Yuichi Yokoyama’s Garden, about a year and half ago, I was dumbstruck. I didn’t think that it was possible for me to have a new experience reading comics – and yet, Garden was just that. As fresh as a spring flower. I have read it many times since, as well as some of Yokoyama’s other books and I have become convinced it is an important book – not just in comics, but in art and literature and culture. When we step through the break in the fence on the first page, it's like sliding down the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland. After I read Garden, the world seemed different to me.

Tom: I was surprised to see it on your bookshelf, it stuck out like a sore thumb. We haven't spoken much, but from what I've read by you, I took you to be a "klassic komics" kind of person. I was surprised that you had one of the most far-out, modern comics I've ever read. I had a similar experience reading Garden. How did you come across it?

Paul: I am often taken for a "klassic komix" type -- I guess because I have mostly written about older stuff. But, for me, a hundred-year old comic that is good and speaking to me is in some ways no different than a comic made yesterday. Good work lives in the moment, no matter when it was made. But -- that being said, I bought Garden and some of Yokoyama's other books through the mail without knowing a thing about them. It was part of a concentrated effort to learn about some newer comics. I loved that I could, in the same year, study American newspaper comics from the 1900s and the just-made work of a Tokyo artist. That speaks to the richness of the form and what's available to a modern reader in the United States. Dan Nadel’s interesting to me because he's done these books of "klassic" comics -- meaning old stuff (but also obscure) -- like Art Out of Time (Abrams ComicArts, 2006) and Art In Time (Abrams ComicArts, 2010) -- and he also clearly understands something about what's happening this very second in comics -- and I wanted to tap into that a little. PictureBox had a going out of business sale at 50% off and since that was around Xmas time, I gave myself a holiday gift and ordered a bunch of stuff. I remember being taken with PictureBox’s description of Yokoyama's World Map Room (2013). It was something like: "Some guys walk around in a city. That's all." I thought, "How cool." Then I got his books and read Garden and it blew the top of my head off! It's a modern klassic!

Tom: Oh, lucky you! I wish I had known about the sale, I paid top dollar over at Elliot Bay Books!

Paul: It’s worth full price! Speaking of Garden being modern -- one reviewer called it "Manga 2053," meaning manga from the future. How did you first intersect with Yokoyama's work and Garden?

Tom: Someone I knew pointed it out when we were looking through the graphic novel section of Elliot Bay. I flipped through it and was immediately blown away. I didn't buy it right away, but the imagery stuck with me, and I bought it a few months later. I had never heard of Yokoyama, and my knowledge of manga is pretty limited, but this certainly was unlike anything else I've read.

Paul: Have you read any of his other books besides Garden?

Tom: Only World Map Room, which was a completely different reading experience.

Tom: Only World Map Room, which was a completely different reading experience.

Paul: I also just want to mention that I have a strong connection with WORLD MAP ROOM because I actually have been in a World Map Room – in Boston, at the Christian Science Monitor’s building. It's called the "Mapparium." You walk inside a huge glass globe of the world. I wonder if Yokoyama knows about that. I've read New Engineering (2007), Travel (2008), Garden (2011), Color Engineering (2011), and World Map Room (2013) – all published by PictureBox. I'm curious why, for you, Garden and World Map Room are different reading experiences. They are very similar in some ways -- a group of strangely dressed people move through a weird place with great purpose and curiosity. How would you say the two books are different?

Tom: Garden was a completely unique reading experience. I kept grasping for things to compare it to. It's a bit like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but without a guide and without candy. The number of characters is absurd and hilarious, I could never get a good count. Maybe two dozen? The dialogue was almost purely descriptive of their bizarre surroundings, and could have been made by any one of the characters.

As a cartoonist I'm pretty hyper aware of this type of thing, but the word bubbles oftentimes would point to nobody in particular, or someone's foot or their shoulder. There seemed to be more of a discernible plot in World Map Room, and lots more tension. The characters seem to have much more individuality bestowed upon them. The book reads more conventionally, and when I finished it felt like the first part of a longer story. Reading Yokoyama's author notes at the end, it's apparently the first part of an unfinished trilogy.

Paul: I love the comparison with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory! That’s especially interesting because I know Roald Dahl also wrote this wicked satirical short story, "Neck," about people being used in a totally impersonal way in relation to a bunch of large chess pieces made from topiary that sit in a huge garden. And in an interview or a review somewhere, the point is made about how Yokoyama doesn’t create characters but instead uses figures as impersonal placeholders, as though they were chess pieces. I think that World Map Room, which is more recent than Garden, hints at a narrative, without really giving us one. There is the highly defensive reaction the figures we are with have when they encounter another group -- there's something ominous hanging in the air, but we never know what it is. In Garden, there's just one homogenous group. By the way, I counted something like 200 figures in one panel, on pages 52-53 in Garden...

Tom: Good God!

Paul: I love that about the book... you start out thinking you are following a small group of four or five... and then, without calling attention to it, it is revealed quite naturally that a very large group is moving and talking as one person through the fantastic and mysterious landscape.

Tom: Yeah, and the fact that a group so large is sneaking around. The whole book is imbued with a quirky sense of humor. I especially loved the character who was always taking photographs. At one point I thought that was maybe just his face, as though his face was just one giant flash.

Paul: Yes! This large group is supposedly sneaking through the Garden, which in the very first panel we are told, "ain't open today." They never see anyone else there, although there is evidence that someone might be just ahead of them. I also thought maybe the flash was the guy's face -- but at the end we learn he was taking photos and then we get to see those photos develop, like the old Polaroid style images -- and that's when the story stops, when those photos replace the "actual" things we've just seen. It's an intriguing ending. I was careful to say the story "stops," and not ends -- because it's clear the action keeps going even if there are no more pages. I sometimes wonder if they ever get back out of the Garden!

Tom: Yet you never see his face!

Paul: Well, as far as I can tell you never really see anyone's face. They all are wearing different hats, helmets, masks, visors, glasses, and so on. Some of which is totally impractical like the bubble helmet guy with the antlers sticking out.

Tom: Yeah, I really liked the umbrella guy too. Very high fashion!

Paul: Yeah -- I liked him too! Really funny!

Tom: The costumes in World Map Room weren't nearly as outlandish. If their heads weren't bizarrely shaped they wouldn't look out of place at fashion week. This being the first book by Yokoyama I've read, I found the ending of Garden very pleasing. You got some hints at some of the goings-on behind the scenes, but he didn't spoon feed you a tidy ending or hit you over the head with a Grand Statement.

Paul: Now, are you speaking of the ending when the photos develop (while a hurricane in the background tosses around leafless, tree-sized logs like they were matchsticks) or the additional section at the end of the book that loops back into a few sections in the book to explore more of what happened?

Tom: Both. The photographs developing with the storm in the background was weirdly poetic. I think that's the True End to the story. The extra bits were almost like a glossary. I'm not sure if you were supposed to read them when you saw the footnotes, but I saved them for the end.

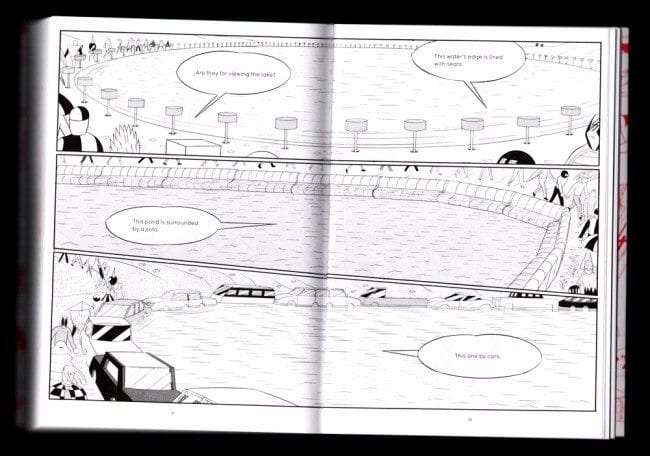

Paul: Me too. What I liked about those sections at the end is that it kind of invites you to look at the 300 or so pages you’ve just experienced with the same wonder, awe, and puzzlement with which the characters approach the structures in the Garden. You get hints of behind-the-scenes stuff that suggests there’s more to all this than we can ever know. And in a weird way that’s like life – we are born into this place that we never really truly understand. Taking a walk through a really cool city or a forest can be just like walking through a place where cars combine with trees to make weird sculptures, and there’s a lake surrounded by a sofa, for no apparent reason.

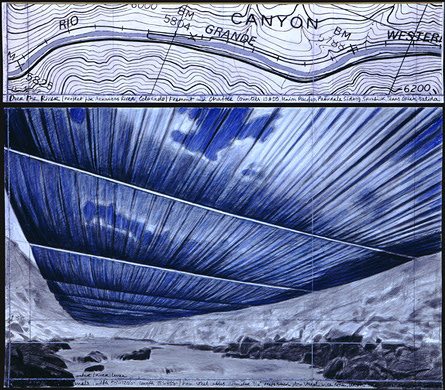

Tom: Right, it's like strolling through the ultimate art installation. In fact, it reminded me of the hanging cars by Cai Guo-Qiang at the Seattle Art Museum, or an installation by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. They would fund their installations by doing detailed drawings of their plans and selling them. I saw some at the Albright Knox in Buffalo, and they're not dissimilar to panels in Garden. But by making a comic, he gives these sculptures a sense of time. He has explicitly said that that's why he began writing comics, to show what happened before and after one of his paintings.

Paul: Yes, Yokoyama has said "I draw time." One thing I like about your work, Tom, is that it is strong on narrative continuity -- to me this is one place where you might intersect with Yokoyama. As you point out -- he wants to discover the events before and after a single image he might paint. Garden works so well because it is relentlessly linear -- and as such, it's easy to follow the action. We can relax about what's going on and just enjoy the ride -- as if we had stepped into a little amusement park boat pulled through the water and all we need to do is marvel at the spectacle created for us to enjoy as we go through it.

Tom: Exactly. I really admired the clarity with which he drew and how easy and clear each panel led to the next one. And thank you, one of my main goals when making comics is to have them be as clear and readable is possible. For most of my strips I don't even change panel size, and for the longest time I abstained from using word bubbles. I eventually started using them, though. I think that someone who had never read a graphic novel before could enjoy Garden, after they got used to reading right to left, of course.

Paul: I've managed to make a few pages that had a clear internal logic to them and wow was it a lot of work! I am in awe of folks like you who can figure this stuff out. I should be careful using the word “narrative.” Yokoyama is not telling stories in the traditional sense – that is, stories that offer meanings in the typical ways, such as using mimesis. In Garden, there’s an alien, almost insect-like point of view – no emotions, no concern at all with what anyone is feeling. That sounds awful, but it actually can inspire a stronger sense of wonder. If a bug wanted to tell a story, they wouldn't talk about feelings or anything related to the human experience. Instead, they'd say "Next, I crawled across this long flat surface until I came to a mountain of white crystals." And that's how they would see the kitchen counter with sugar on it. Plus, the travellers in Garden don’t act the way a large group of travelers would in the real world. When I go on a trip with just a couple of other people, we have to stop every so often and argue about which way to go and how to proceed. In Garden, there’s no conflict. It’s sort of Paradise – the Garden of Eden -- in a way – where there’s no struggle, no war, no split minds, and nothing of the illusion that we are separate from each other.

Tom: Right, the large group always follows one another and never argues. There is a hint of tension from the security in the garden, but everyone follows one another, even when their path is exceedingly dangerous. It was like watching the computer game Lemmings, but you won every level.

Paul: I like your art installation comparison. It works really well because we know that Yokoyama is as much a "fine" artist as he is a manga artist. Yokoyama seems to be coming from a fine arts vector into comics. There are lots of comic book artists in America who start with the intention to make comics -- either mainstream superhero stuff, or the various strains that are popular in the US -- like autobiography, and so on. And their training and background comes mostly from comics -- so that their work becomes very limited, sometimes. But I've noticed lately that there's a new crop of comic book artists who do comics as part of their fine art, and they are pulling in all sorts of new influences and ideas. I think this is really interesting. Yokoyama-- who is now 48 years old -- has said in interviews that he doesn't read other manga. In 2004, he also said he didn't own a computer, phone, or a driver's license!

Tom: Yeah, he seems to live in as much of a cultural vacuum as you can nowadays from the interviews I've read. Though who knows, he contradicted himself a bit between the interview for Comics Alliance and the one with Dan Nadel in New Color Engineering. He may be controlling his own image a bit. I actually went to school for printmaking and didn't do comics for many years. I always wrote short stories and made zines, but never thought to make a comic. I didn't really read them growing up.

Paul: I am just the opposite. I actually was reading before I started school because I wanted to know what Little Lulu and Donald Duck were saying. My entire education rests on comics! Do you see any other connections between your work and Yokoyama's -- do you feel an affinity with what he's doing at all?

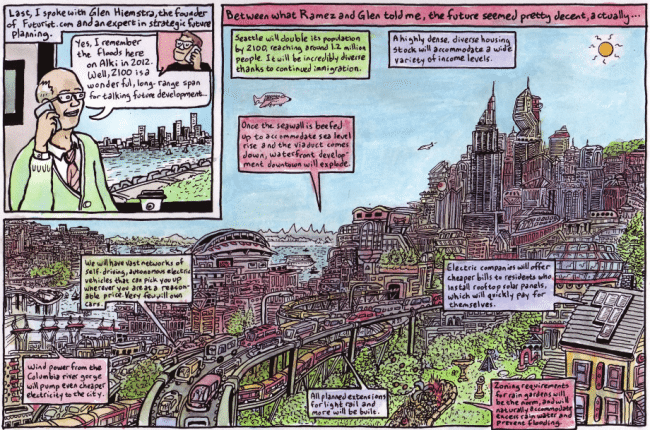

Tom: I only discovered him about six months ago. Most of my work is satire, written as autobio but completely fictionalized. It's more influenced by Albert Brooks or Alan Partridge. But I've done a few strips that star animals that definitely don't take place in the real world. I think that work is more similar. But to compare the two may be a bit of a stretch.

Paul: If I were going to find established artists to compare you with, I'd probably pick folks like Gilbert Shelton and Robert Armstrong -- in fact, your cartoon version of yourself as a totally self-absorbed, gluttonous degenerate reminds me a lot of Armstrong's delightfully incorrigible Mickey Rat character. But I can also see a similarity with Yokoyama in the way you both like to present outlandish things with a perfectly straight face, which of course is the comedic style of folks like Albert Brooks. And I note that you and I both like a musical act that operates that way: Sparks. Whether it's a character dressed in an umbrella or a character that is hopelessly and unapologetically degenerate -- it's the sobriety of the presentation that breaks like a tidal wave against the idea -- a great effect. You have three comics out now, Scorched Earth 1 and 2, and the just published EAT EAT EAT They all present you as a slob, having drunken misadventures. Why do you show yourself in this way? You don't have to answer that if you don't wanna.

Tom: No I'll totally answer that haha. I've been criticized before for having a completely unlikable protagonist in those stories. But I think some of the funniest stuff ever written has obnoxious, loathsome main characters. My favorite book is A Confederacy of Dunces, in which John Kennedy Toole makes a semi-autobiographical version of himself as a disgusting, but highly literate, slob. Toole went on to kill himself, though, I have no similar plans. Even before I wrote comics I wrote fake autobiographical stories, either in zines or for creative writing classes. It's easy and fun to make myself out to be a monster, and I can satirize bad behavior I see in myself and others. Hopefully it can spur some self-examination from the reader.

Paul: I agree that this approach can be very funny -- and your stuff makes me cringe and laugh at the same time! It's effective because it's showing a truth about human nature that is hard to put into words. What do you make of this 2014 quote from Yokoyama? “I believe that things can't be described with meanings or words. Ultimately, I want to show that. It is difficult. People try to use words to describe. I think it is wrong. I think there are many things which can't be described in words. People think we can replace everything in words. I think most things are not described yet. We can't exactly describe why this food is delicious. We can't explain hot and cold to the people who don't know about it.” To me, this kind of gets at what makes Garden special.

Tom: Yeah I totally agree! That quote gets to the heart of the matter. The world is endlessly complex, and we will never know what is going on entirely. Human knowledge only hints at what is going on in the universe, and we can only speculate on what's going on using the knowledge and data we have. Even if your beliefs are somehow entirely scientific, it's still likely that your worldview is deeply flawed, because we simply don't know everything. Reading Garden, you can only marvel at his inventions and sculptures, and speculate on their meaning.

I actually disagree with Matt Seneca's reading of the ending. I don't think Yokoyama had that direct an agenda or criticism of modernity and technology. I think to impose such an agenda on the book cheapens it a bit. But I do like to hear other people's opinion on the book, since it's so profoundly weird.

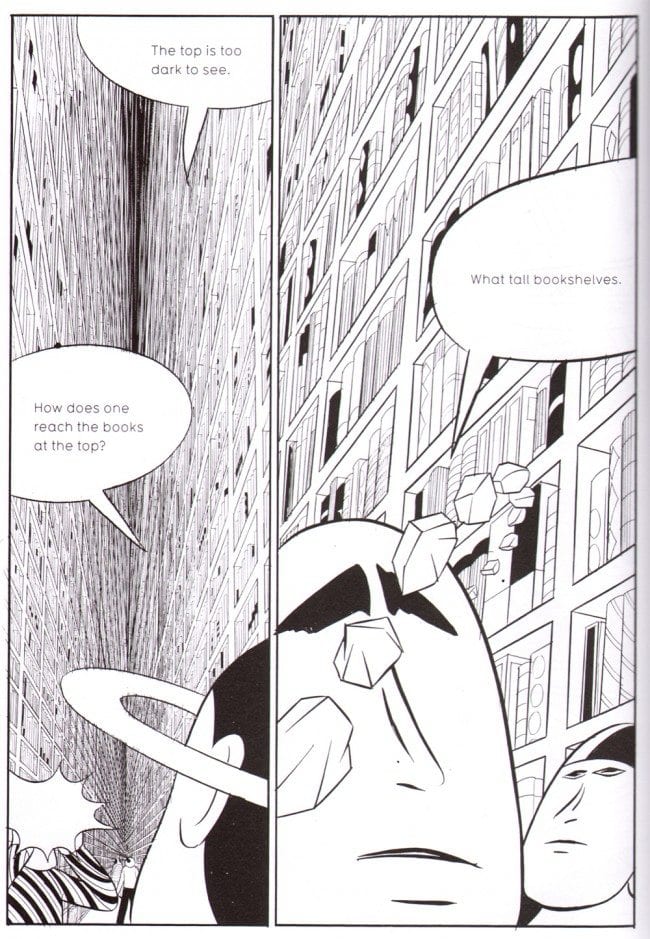

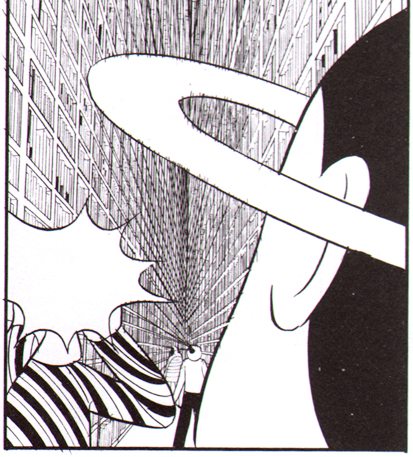

Paul: That’s well put. Garden is clearly a force to be recokned with and, as such, it's tempting to read meanings into it that may not connect to anything its creator had in mind. Some reviewers, such as Matt Seneca, talk about Garden being a sort of metaphor for the evolution of human civilization -- which is a really smart and exciting idea, but I kinda think that Yokoyama is just doing his thing without a lot of self-reflection. In interviews, Yokoyama speaks less about his deeper meanings and more about intuitively doing what he likes, such as drawing faces. Or making objects really large, like the giant #4 drip coffee filter that the people in GARDEN encounter -- it's like a huge five-story teepee to them! Or that library -- a really massive library, with some really large books!

Tom: Yeah, and those are the sort of scenes I'm most drawn to. His perspective drawing in that library scene is truly something to behold, and can only really exist in a drawing. The shelves go on to infinity. It's so cool! It's obvious to me when an artist is enjoying what they're drawing, or are having fun. Like those endless cityscapes in World Map Room, it's just a few pages of them looking at the city. So often with comics, you have to draw things that you don't want to tell a story. When I draw my real-world stuff, I always have to look at reference photos and such. Not much fun. But when I can draw whatever I want in my sketchbook it's a hoot, and for me, it's a lot more fun to look at.

Paul: That sketchbook drawing looks to me like it was something done because you wanted to do it. I think it's important for an artist to have that drive -- but also to exert some discipline to shape it. It's the difference between Charles Crumb's obsessive noodlings and Robert Crumb's self-aware distillations of his own obsessions. What I like about some of the scenes in Garden is that Yokoyama keeps trying to top himself. I mean, it's pretty incredible to think of drawing a vast, super-mega library -- and he pulls that off. Then, it's like: let's look at some of the books in this place. And so we start getting drawings inside of drawings -- and the books are hilarious. A collection of cars, or a book of animals. And then a mysterious book of pictures of everything in the Garden. And then they pull out a really long book that takes several guys to wrangle (hey -- how come there don't seem to be women in these books?) and it's a book of -- of course -- trains! And then a super tall book is a life-sized book of humans. And then an even taller one: trees! It's a tour de force! Looking at that sketchbook cityscape of yours - and talking with you about Garden -- I want to go walk around in that drawing you made!

Tom: Yeah, exactly. Garden is a place more fun than the real world. Even Seattle! Yokoyama has some serious drawing chops to pull all this off. Some of those drawings are almost like Winsor McCay, and his use of panel size and structure are similarly inventive. To show a book that tall he uses super tall panels, it's a really clever way to show scale.

Paul: Yes, his skill with rendering is phenomenal, and his abilities as a visual storyteller are extremely inventive. When I first started seeing the way he broke up his pages and panels and managed to communicate with absolute clarity it reminded me of another "fine" artist who did comics - Lyonel Feininger. This artist, more famous for his paintings, was also concerned with exploring the relationship between humans their environments and came at comics from a radically different entry point with major art chops. Another visual aspect I like about Yokoyama's work is the omnipresent sound effects -- laid over the pictures like decorations as much as anything that communicates meaning. That's something that only someone who comes at comics from an outside place would think of making a major art element in their work. People who read comics a lot are probably mostly blind to the visual impact of the sound effects, because they have learned to just integrate in to their experience of the story. PictureBox's books offer translations in tiny print under the sounds -- so the sound of a tool telescopically sliding out is "SURUSURUSURU." The sound a river makes changing course is "ZAAAAA." This is great stuff -- I love it.

Tom: Yeah, he somehow makes onomatopoeia sexy! Sometimes there's more than one translation, too, like there's the sound effect, and then what that sound effect is supposed to represent. It must be hard to translate that stuff.

Paul: Just another artist's name to toss in: Jack Kirby. When I first started reading Kirby's stuff, in the seventies, he was drawing these vast, building-sized machines. I used to study them and imagine myself walking around these mind-blowing structures. So, when I found Garden, it was really satisfying for me in that it finally fulfilled that dream! Even though Yokoyama apparently developed his work without any exposure to Kirby, I think he's drinking from the same well. I mean, just the forceful, dramatic way his people move -- he's clearly on the same wavelength. Before we close this discussion, any last insights about Garden that you wanted to toss in?

Tom: I think we covered the main things I wanted to discuss! I could honestly yammer about this book all day, but if, for some reason, someone is reading this having not read the book, I encourage them to pick it up!

Paul: I agree -- I hope this will inspire some folks to go try Yokoyama's work. There's so much cool stuff in Garden that we didn't even touch on! Tom, I thank you for taking the time to talk with me about Garden. I’ve really enjoyed it. And, I look forward to reading more of your own comics and stories!

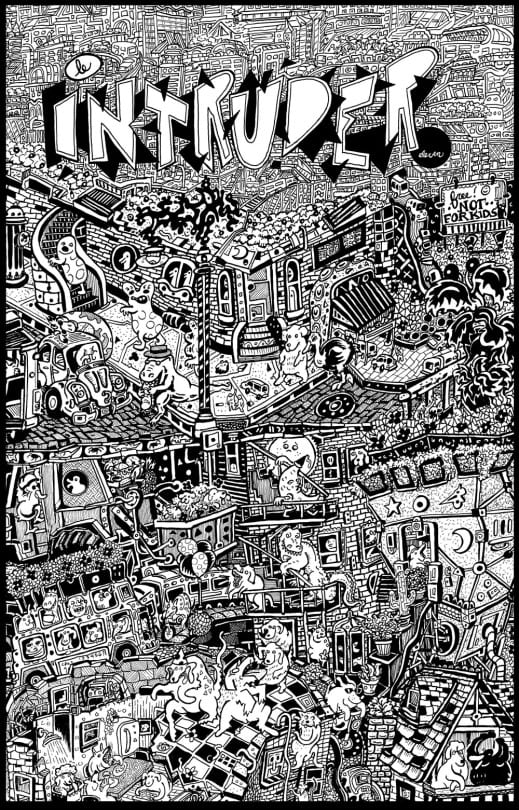

Tom: Happy to do so, and most of my stuff is serialized in Intruder, so keep reading that!

_______________________________________________________________

Tom Van Deusen is a part of the group of emerging Seattle artists working in comics who regularly publish the comics newspaper, Intruder. He studied art at the University of Buffalo and helped found the Buffalo-based art collective Sugar City. He has three comic books currently in print from Poochie Press: Scorched Earth and Other Stories (2013), Scorched Earth Volume 2 (2014), and EAT EAT EAT (2015). His website is: tomvandeusen.tumblr.com

Paul C. Tumey is a writer, artist, and cartoonist in Seattle, WA. He co-edited and wrote for THE ART OF RUBE GOLDBERG (Abrams ComicArts 2013), and wrote the introduction to THE BUNGLE FAMILY 1930 (IDW Library of American Comics, 2014).

All art from Garden is copyright 2011 PictureBox and Yuichi Yokoyama. All of Tom Van Desusen's art is copyright 2015.