What precursors even exist for comics like Colville by Steven Gilbert or Black River by Josh Simmons? These are books that use genre not to entertain, but to carve away at something rotten. They document a kind of moral entropy—the creeping disintegration of everything right and good. The universe they depict is unjust, indifferent; their nihilism can be suffocating. The stories proceed according to the predetermined, inescapable logic of the snuff film: the people you see here are destined to die, and you are reading these comics because they will die.

Even the bleakest horror and crime comics are seldom so black. Al Columbia’s desiccated cartooning retains a shimmer of real beauty; the inevitable deaths in Julia Gfrörer’s stories are nonetheless charged with illicit pleasure; Jacques Tardi’s gruesome adaptations of Manchette at least end in perverse good humor. There are few such redemptive touches to Black River or Colville, aside from the craft of either cartoonist, where the feats of sheer drawing and weird, propulsive pacing can often be thrilling. Still, the moral ugliness of these books borders on the repellent—which is all the more reason to grapple with them.

Even the bleakest horror and crime comics are seldom so black. Al Columbia’s desiccated cartooning retains a shimmer of real beauty; the inevitable deaths in Julia Gfrörer’s stories are nonetheless charged with illicit pleasure; Jacques Tardi’s gruesome adaptations of Manchette at least end in perverse good humor. There are few such redemptive touches to Black River or Colville, aside from the craft of either cartoonist, where the feats of sheer drawing and weird, propulsive pacing can often be thrilling. Still, the moral ugliness of these books borders on the repellent—which is all the more reason to grapple with them.

Steven Gilbert’s Colville was already pretty grim when he self-published its first—and for a long time, only—installment in 1997. (I’ll be discussing some major plot elements of both books, so fair warning to readers who’d like to preserve the gut-churning surprises these authors have orchestrated.) Over those first 64 pages, small-town high school student and morose young offender David plans an ill-conceived heist with an old acquaintance, while looking forward to a young-love-on-the-run future with his similarly brooding girlfriend, Tracy. David’s scheming eventually leads to his crossing paths with a power-mad petty criminal named Alan Gold, as well as a yuppie psychopath who happens to dig mini-comics.

Gilbert hatches the proceedings into blackness just this side of Burns, a somber thicket through which we see fixed sporting events, a botched drug deal, midnight assignations and, startlingly, a nightmarish few pages involving roofies and rape. This violation occurs at the hands of a shadowy figure who most readers would probably peg as a poor imitation of Patrick Bateman, but who some will identify—thanks to an disarming and downplayed revelation—as serial killer Paul Bernardo, whose preying grounds were Ontario exurbs much like the cartoonist’s fictional town of Colville.

Needless to say, in that initial comic book, things do not end well—but what’s alarming about the hundred-plus pages that Gilbert has added to the new edition is that everything then gets much, much worse. Not only does Bernardo play a larger and unforeseeable role, but so too do the biker gangs that enjoyed their heyday in the province during the same time. (The artist’s fascination with a disavowed history of unsavory brutality in Canadian life carried over into his 2013 comeback, The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge.) When the book flashes back to the shooting and flaying (yes, flaying; sorry) of Alan Gold’s wife by his former biker brothers, or when Bernardo and his wife and accomplice Karla Homolka seize and defile their next victim, all movement slows to a crawl. Brain-shots, garroting, ejaculation, flesh tearing—all have a visceral impact on page.

Tellingly, the murder that begins the book replays throughout, cut free from chronology like a traumatic memory, as each character relives that shattering event from his or her own perspective. (Gilbert recalls Chester Brown’s recursive and similarly shocking Ed the Happy Clown in these moments; in others, he anticipates the aloof and distanced killings of Louis Riel.) Throughout Colville, violence unfurls in a stilted, awkward, slow-motion stutter-step that doesn’t sensationalize the action so much as it emphasizes its ineptitude and irreversible wrongness. Violence isn’t something these characters walk away from, as they would in any other innocuous thriller: instead, it haunts them, it defines them, or it does them in entirely. In Colville, violence is a rupture in the fabric of being.

Violence also erupts unpredictably in Black River, which like Colville directs deliberate, thoughtful, lingering looks at pure contemptible baseness. Josh Simmons makes suffering into a book-length spectacle here, following up the short scabby stories collected in 2012’s The Furry Trap. Black River treads familiar post-apocalyptic ground—think The Road, but filmed by Herschell Gordon Lewis—as a determined group of women (and one ill-starred man) traverse blasted landscapes under lowering skies, searching endlessly for sustenance and shelter. Simmons hacks their story into three chunks: before, during, and after the central sequence in which they are kidnapped, raped, and some of them murdered, before the survivors achieve a pyrrhic revenge.

This confrontation between the women and their Duck Dynasty-looking captors (as well as a clean-shaven charismatic killer named Benji, a counterpart to Colville’s boy-next-door Bernardo) serves as the dark heart of the tale, and the only one in which time unfolds consecutively. A series of deceptive vignettes lead up to, and stagger away from, this brutality mired in the middle of Black River. At the beginning of the book, there yet exists some promise and purpose, however precarious. A cache of clean socks and booze provide a glimpse of the good life for the gang, and soon they listen to an old comedian do a routine that testifies to a stubborn, if despairing, instinct for survival. “Now,” he says, “I wake up. I find food. Or I don’t. I walk. I sleep.” (I’ll spare you the punchline.)

By the book’s end, though, and after the women wreak vengeance on their assailants, that initial insistence on clinging to life and its few remaining pleasures has been fully stamped out. The prospect of a warm shower gets greeted with indifference at best; the philosophy to which Simmons grants final word is no longer one of reluctant perseverance, but of complete annihilation: “I don’t want to leave a trace that I ever existed in this world.” The only hope that Simmons proffers, in the book’s chilling final pages, is that this desire for extinction might be achieved: the character who voiced these sentiments wanders, alone, through a wintry plain, dwarfed and insignificant, erasing her footsteps behind her.

While these closing images are freighted with ambitious significance, Black River’s art elsewhere only rarely nudges exploitation trappings into this exalted register. I could stomach Simmons’s extremity with greater resolve, were his visuals more commensurate with his vision. (Say what you will of Colville’s at-times wooden figures and jagged faces, but they are always communicative and mood-appropriate.) True, part of what makes the artist’s stories work is their imbalance between style and subject matter—that cartoonish patina he lacquers onto repugnant scenarios. His still-retch-worthy Batman comic perfected this mismatch early, taking an unreal, exaggerated style and genre and granting them fleshy specificity. Simmons’s writing has continued to mature and intensify, as has his more decorative drawing—the uneasy skies, here, rival Gilbert Hernandez’s—but his figures and faces are still locked in an expressive language that renders them silly when they mean to look stern. The result is a tonal uncertainty that upsets the book more than it does the reader, tilting Black River toward the sophomoric when it should be unsettling.

Both books are subject to these kinds of abrupt changes in tone, or direction: determined to go against the grain, they bristle or backtrack and leave readers reeling. They set up goals, near their outsets, that any more conventional genre work—your Stray Bullets or Walking Dead—would pursue as a matter of course. In Colville, after David plans on stealing a dirtbike, we expect to see him execute his plans, then encounter troubles fencing off the goods. Instead, Gilbert kills David off, fracturing the story into pieces that never fit back into the original template: these characters become too broken and warped. The women's scheme in Black River was to trek onwards to Gattenburg, a fortified settlement where it’s rumored that safety and some semblance of civilization are possible. Suffice it to say they have no such luck. In either case, the cartoonists interrupt and abandon these best-laid plans as though to mock the audacity of their characters, that they would ever presume they might one day attain some meaningful end, or dare think of the future as anything other than futile and thankless. All that awaits these characters are the void and unpeopled vistas of Black River’s final pages, or the greyness and murk that cloud over the ending of Colville.

These visions of erasure that close out each book may be unexpected, but only because the stories themselves seem to care so little about human existence being refined into nothingness. Instead the books deal with the brute, coarse fact of bodies in pain. On one hand, then, it makes sense for Black River and Colville to arrive at an image of bodies disappearing or dissolving, no longer subject to the abuse they endure. But the fact remains that, for all that these books seem to abhor the effects of violence and rape, they still dwell on the perpetration of such acts at uncomfortable, almost leering length.

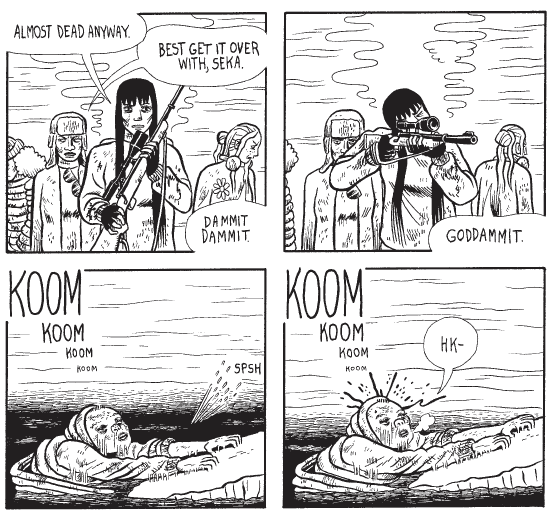

At several points in Black River, Simmons subdivides the violence across several panels, as though it required attentive analysis. A woman’s naked body, her skull caved in by a rock, gurgles and spits for a page before dying. A suicide by gunshot freezes mid-air. A mercy-kill drags out emphatically over a series of frames. That stand-up comedian is split through his trunk with a blade, again and again. This scene takes place on stage, before an audience, much like how the women will soon be besieged in a defunct amphitheater: gather round, folks, we are meant to be watching.

Colville also depicts violence as spectacle, each panel ticking by silent and aghast, because it is to some degree about witnessing, and the trauma of vision. Alan Gold’s toddler son sees his mother murdered. Gold himself relives and looks back on the deaths he’s been involved in. Tracy is forced to watch her boyfriend’s demise. But at some point this kind of witnessing begins to align too closely with Bernardo’s vision (indeed, upon rereading, it seems as though the book originates from the killer’s point of view). From this perspective, events are replayed and slowed down not because they’re traumatic and difficult to process, but because they provide an almost sexual comfort: a videotape rewound and stepped forward again and again, a snuff film revisited with sadistic glee.

More than any gore or nihilistic outlook, this is what makes me most queasy about these books: that at some point in reading, I seem to be no longer standing by and watching these events, but being invited to revel in them instead. Why envision a future so bestial and vile, if only to condemn it? Why choose to view the world through Paul Bernardo’s eyes, let alone the lens of his video camera? What is the point of watching the women in these stories suffer rape, and humiliation, and disfigurement, and murder? Black River and Colville posit that there is, precisely, no point to these actions; they serve no purpose, other than to illustrate the uncaring caprice of fate, and humanity’s inborn malevolence. Simmons and Gilbert dramatize these claims bluntly, sometimes beautifully, and always effectively. Still I can’t help but balk at what they achieve: assured, painful visions of bodies made meat.