The following post will contain tributes to Yoshihiro Tatsumi (1935-2015), the pioneering Japanese cartoonist who passed away on March 7th.

The following post will contain tributes to Yoshihiro Tatsumi (1935-2015), the pioneering Japanese cartoonist who passed away on March 7th.

Adrian Tomine:

There are a few cartoonists whose work literally changed my life, setting me on the artistic path that I continue on to this day, and Yoshihiro Tatsumi is one of them. It was an unbelievable honor and privelege to participate in the translation of his work, second only to the improbable, dreamlike experience of spending time with him in cities as far-flung as Tokyo, San Diego, Los Angeles, Toronto and New York. For the most part, we spoke with the help of an interpreter, but that fact now seems hard to reconcile with the vivid memories I have of our free-flowing, wide-ranging conversations. It didn’t take long for me to discover that, despite differences of age, geography, history, etc., Tatsumi-sensei reminded me very much of all the other great cartoonists I’ve had the fortune of becoming friends with. He could be taciturn and occasionally inscrutable, but in the right circumstances, he'd open up with humor, inquisitiveness, and an unflagging excitement about the process of making comics. I'd studied and learned from his work since I was a teenager, but I think Tatsumi's humility, generosity, and artistic determination were as inspirational to me as any of his stories. I had several occasions--usually when one of us was dashing off to catch a plane--to offer my best attempt at a bow and to say “thank you,” but I always felt that I hadn’t been clear or emphatic enough, and that he was too modest to fully accept all that I was thanking him for.

Anne Ishii:

It’s difficult to explain why Yoshihiro Tatsumi mattered so much. This is not for lack of evidence where it concerns his unquestionable talent, nor for any sophistry over language or authenticity. The difficulty in writing an appreciation worth this honoree, lies in the fact that Tatsumi as a phenomenon challenges all preceding notions of time, culture and context in a way that will impact how Westerners approach manga, forever.

I speak from many points of view whose North is Japan. My only direct interaction with Tatsumi was as a mere interpreter on his NYC tour in 2006, but I can vouch the many tributes we’ve made over the last few days to his humility and kindness. He was as enthusiastic about sketching employees at Forbidden Planet as he was to be on on-stage with Adrian Tomine at the PEN America Words Without Borders conference. He smiled for every camera. He mostly took his social cues from his wife, who also almost convinced me to give her the shoes I was wearing (she liked them and suggested multiple times they’d be impossible to find in Japan). The ubiquity of last names is a function of Japanese morays; not unlike calling your first grade teacher “Mrs. Johnson” well past your school days. Using my first grade teacher’s first name feels tantamount to stroking her cheek, but Mrs. Tatsumi definitely seemed like a first name kind of lady. Anyway, she was the force of energy behind Mr. Tatsumi during their tour through NYC, and I do mean “force” almost literally. She shared some advice with Peggy Burns and me at one point: “a woman has to crush their man a little (Mrs. Tatsumi makes a tight fist with her hand to punctuate “crush”), in order to rebuild them (palm opens flat).” She art directed the pictures we took with him—“smile bigger!” “try tilting your head a little”—and gave anecdotal backup to Mr. Tatsumi’s observations, most of which came from their many years not as manga creators but as manga sellers. Little did I know the Tatsumis ran a bookstore. That such a gem of humanity, to say nothing of comics art, was hidden amidst towers of books for sale alternately endeared and saddened me. If all else fails in the world, I believe we did ourselves a monumental good bringing Tatsumi and his work, out of obscurity.

And obscure, he was.

When I was first introduced to Tatsumi’s work, I was working full-time on publicizing and marketing Osamu Tezuka titles for Vertical Inc. Now, Tezuka’s role in the canon is probably not lost on anyone reading this appreciation, in this particular publication, but at the time (early 2000s), explaining “adult-oriented” Tezuka to the general public was an agonizing deliverance. I felt like a stroke victim unable to adequately communicate my basic thoughts, but I watched with delight as incredulous editors discovered the riches and delights of his latter-day work. I learned through this experience the importance of discovery and to be patient with each process. I can say today that it was worth having the public Japanese record of Tezuka’s deity-status taken for granted so many years, to see the grandness of Western appreciation today. In other words, better late than never.

I bring this up because in many ways, the discovery of Tatsumi’s work was the equal and opposite of Tezuka’s, philosophically and linearly. The fact that Tatsumi’s critical mass occurred in tandem with Tezuka’s, was almost hilarious at the time to the Japanese, but funniest of all to Tatsumi himself. At the time “Push Man” came out, no one in Japan would have been able to identify Tatsumi; Tezuka, meanwhile, was making his Nth appearance on a postage stamp. Tatsumi auto-corrects in Japanese to “tatami.” Tezuka has a theme park. Suffice it to say there are no Tatsumi theme parks (in fairness, the idea of one horrifies me). I asked Tatsumi to blurb Tezuka’s “Ode to Kirihito” and I could almost hear his breath stop through the email. He spelled out his guffaw, found difficulty expressing what an honor it was merely to be tasked to such an order. His shock bordered on shame. At the time, I believe I told him something regrettably condescending, like, “yeah but you are huge here in North America!” What I meant was, “our distributors like seeing your name on comp titles because they’ve had great sell-through, which is ultimately the only proof we have for the salability of our books, so demonstrating some kinship would be really great for POS. —Love, Marketing Dpt.” Until Drawn & Quarterly’s lovely editions of his collected and freshly attributed gekiga, Tatsumi and Tezuka’s only kinship was alphabetical.

My point in all this dichotomization is to prove how these eclipsing legends have created a singular event in manga—a western edition has shown Japan its own treasures. To borrow from that earlier cited Marketing Department, this has been a testament to retro-acculturation. And now the canon has awakened, the blooms of obscurity can be smelled, the translator has let her hair down. Tatsumi and his work have done more to contextualize manga and comics across time and space more than most anyone, and did so with a richness, a darkness, an uncanny that makes him universally ours to love and behold. He will be terribly missed, but he will be forever remembered.

—————————————————

Joe McCulloch:

For the English monoglot, reflections on Yoshihiro Tatsumi have a way of becoming reflections on localization: of translation, packaging and promotion. There is a striking exchange in the q&a at the back of Drawn & Quarterly's Abandon the Old in Tokyo (2006) where the editor and designer of the English edition, Adrian Tomine, asks Tatsumi if he had ever drawn any longform books besides 1956's Black Blizzard. Tatsumi replies that he'd drawn twenty for the lending market of the time. D&Q would release a Tomine-edited edition of Black Blizzard in 2010, but the others remain obscure.

It is useful to remember that Tomine, as related in his introduction to The Push Man and Other Stories (2005), himself first encountered Tatsumi through a glass of sorts: Catalan Communications' 1988 edition of Good-Bye and Other Stories, a book translated from Japanese to Spanish to English and purportedly released without Tatsumi's knowledge. The Catalan edition shared contents with an earlier Spanish release, La Cúpula's Qué triste es la vida y otras historias (1984), which was packaged bluntly to highlight the comics' erotic potential. But Tatsumi was known in Spain even before that, having appeared in several issues of El Víbora, an alternative comics magazine which also published works by Kim Deitch and Gilbert Shelton, and a young Charles Burns, along with numerous domestic talents. Willing or not, he was a participant in an argument being made about the history of global comics, which would recur in the 21st century as D&Q promoted him successfully again in the west as a historical-literary titan - much to the puzzlement of Japan, as detailed by Anne Ishii above.

But why is it that Tatsumi's works have proven so conductive to recontextualization? Lacking exposure to the full dimension of his body of work, I'll resort to metaphor. Black Blizzard is indeed a severe phenomenon. One hundred and twenty-seven pages drawn alone in 20 (that's "twenty") days, the work is an absolute riot of momentum, tumbling forward with diagonal slashes of black weather, monstrous outdoor scenes rendered as if the artist had doused his hands with ink and drawn with his fingernails. Rarely have the players in a crime comic been so diminished by the setting of their drama, though the artist manages very little in the way of geographic specificity - really, we are seeing the world of paranoia, anxiety, threat and regret, externalized as snow cutting and biting like falling shrapnel. Of course we know that Tatsumi was not alone in seeking to push Japanese postwar comics into its adolescence, and drew good influence from the study of his peers, but unlike the studied and ominous work of a Masahiko Matsumoto, Black Blizzard actually feels, somehow, like raw youth: completely surrendered to a fury of motion. We've got to go somewhere, damn it.

Then they all do. The man and the comics age, and the storm recedes just enough to leave the sky a bleak slate gray. If you follow along carefully with Tomine's back-of-book chats with Tatsumi, you'll realize that the late '60s/early '70s stories collected in The Push Man, Abandon the Old and the D&Q Good-Bye (2008) were published in diverse forums, ranging from the famous alternative magazine Garo to Kodansha's arch-mainstream Weekly Shōnen Magazine to unspecified 'adult' rags and small press dōjinshi. Yet there is a fearsome unity to Tatsumi's work that flies completely in the face of forum or demographic; that his works are so completely his own -- their ceaseless, bleak angst about women, change, art, history -- doubtlessly aided his applicability to the western narratives of comics maturity, about artists disregarding concerns for commercial viability to bare all in displays of unfiltered revelation.

It is the atmospherics that rule all. The feeling of being trapped under Tatsumi's lidded sky, which once roiled with young passion and now hangs heavy and dim across multitudinous dooms. Truthfully, I don't think these comics shoulder the load of 'literature' very well - as writing they are uncomplicated sketches lacking in the poetics of a Seiichi Hayashi or the depth of a Yoshiharu Tsuge. Yet I love them so much for the intensity of their communication, and the fatalism that soaks their every step. It's like the engine of progress has stalled, completely, leaving this pioneer stranded in vivid hells without the certainty of genre to promise him anything, anymore.

—————————————————

Jocelyne Allen:

Yoshihiro Tatsumi was the first person I ever interpreted for on stage. And I was definitely nervous, but a lot less so than I expected to be. Because Mr. Tatsumi just had this way of putting people at ease. He always made you feel like he was glad to be with you at that moment and that, in fact, there was nowhere else he’d rather be. While I was his English voice at TCAF, I saw this side of him again and again, with the reporters who came to interview him, the fans who came to meet him (and how he loved those fans!), and the event staff who just wanted to make sure everything went smoothly. He might have been the father of gekiga, a legend in his own right, but he was always humble, always looking at the person across the table from him and listening so carefully, so thoughtfully.

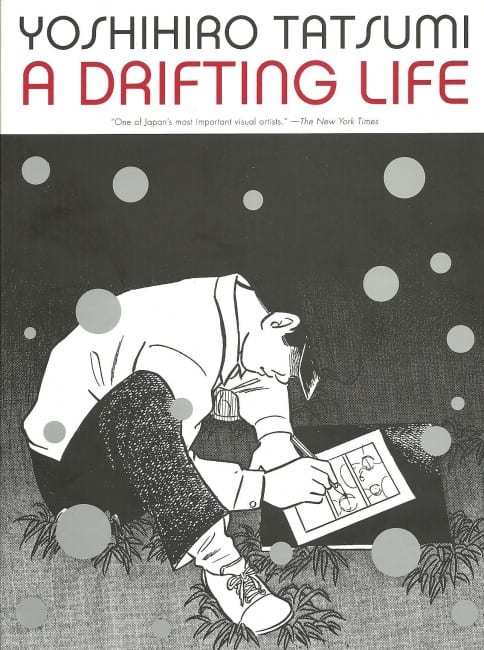

And after I fell in love with his manga, like so many who got the chance to know him, I fell in love with the man himself. Each time I saw him in Tokyo after his trip to Toronto or talked with him over email, that love grew a little deeper. His devotion to his work amazed me. He was always thinking about manga, about where he was taking his work and what he wanted to do next. Even when he was in and out of the hospital, he was creating. He was intent on drawing the sequel to A Drifting Life. Over dinner in his favourite Chinese restaurant, he showed us pages from that sequel; they were beautiful.

There was a day while Mr. and Mrs. Tatsumi were in Toronto when we had some rare free time, a couple of hours between events. I offered to take them back to the hotel to rest since I knew how hard Mr. Tatsumi had been working, staying late at all his signings, unable to turn away a fan without a drawing and a signature in their book, but they both waved off my concern. They were fine; how about we get a coffee? And so we did. Mrs. Tatsumi wondered why I didn’t have any children, while Mr. Tatsumi wondered what the difference between partner and husband was and why didn’t I just get married then? They became my surrogate parents.

One of the last times I saw him, he gave me a copy of Tatsumi, the collection of short stories from the animated film about him of the same name. And he signed it in English, “To Dear Allen,” which killed me with its sweetness then and is murdering me now.

(More to come...)