1.

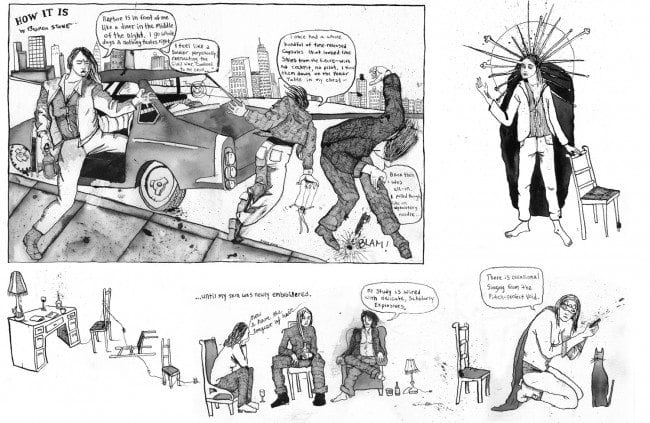

A woman stumbles out of a real clunker, booze in her right hand, muttering to herself—or to someone unseen, or to us. "Rapture is in front of me," she says, "like a diner/in the middle of the night." We watch her twist in a grotesque dance. The booze becomes a marionette then a gun. Then she's Jesus, consecrated. Scene change: an apartment. An extension cord, or maybe wire, strung through chairs to three friends talking over drinks. Maybe the dancing woman is there. Maybe she's all three of the women. In the end she kneels in superhero tights and a cape. "There is occasional singing from the pitch-perfect void," she says. A black mass crumbles in her hand, or explodes, as a cat observes her, unimpressed.

How do we read this poem comic by Bianca Stone entitled "How It Is"? Our eyes dance between word and image, image and word, guided by the implied order of the panels but free to roam. We know the drill: left to right, top tier to bottom tier. Lineation seems random, enjambment determined by space constraints. Despite the sense of progression created by the panels, we sense, too, a static quality. Our eyes might return to a certain image—the woman become Jesus, for instance—and or take in the whole image of this single-page comic. Momentum and hesitation, the impulse to progress and the impulse to meditate, exist in tandem, competing against each other for the benefit of the work and the reader.

2.

Having wandered into the field of comics studies, I recently attempted to define the quality I've described above as "profluent lingering," or—

the result of the variable tensions between a generally narrative progression and a quality of stillness, both of which manifest in multiple media—pages, panels, images and words—that are arranged sequentially. We might also think of [profluent lingering] as the constant negotiation that goes on in the reader's mind between the forward momentum of narrative and the temporary stasis of looking at a single image.

And what a joy that is to read. Ships will be launched over its beauty.

As I've defined it, profluent lingering is simply a term for the competing impulses of narrative and stasis that exist in a comic and are activated when we read it. Certain comics may feel more profluent, others more so a sense of lingering, but each quality always exists to some degree. "Profluence" modifies "lingering" because the visual field is the basis of a comic. There are many comics without words, but few without images, and even those (the poet Kenneth Koch's Art of the Possible! for instance) utilize the flow of visual frames to make meaning.

Even though we generally associate lingering with the image/looking, and profluence with words/reading, the crucial point is this: profluence and lingering are created by all elements of a comic. In the cooperations and tensions of a comic, profluence can be created by images—think of the deft momentum of Norwegian cartoonist Jason's book Almost Silent—and lingering can be centered on words, as is often the case in the narratives of Chris Ware. When it's handwritten, a word becomes image, too. "Profluent lingering" shifts the critical focus toward a holistic consideration of how a comic's form is made, how it's read, and how that reading influences our interpretation. I've been trying to capture a term for the activated essence of comics.

3.

Damn it, though, I forgot about poem comics.

3a.

Not every critic has. Some are really on the ball, you know. In the past three years, discussions about poem comics have sprung up at The Comics Journal, the comics blog The Hooded Utilitarian, Comics Forum, Poetry magazine and The Atlantic. Taken as a kind of critical chapbook, these articles and interviews point to the growing awareness of poem comics as an art form (if also to recurring issues of cultural turf and the challenges of definition and terminology). They also expose a lack of critical engagement with specific works like Bianca Stone's I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant, Warren Craghead's "A Flame Expelled," and Derik Badman's series MadInkBeard. We haven't been paying enough critical attention to poem comics.

Why? If "the language of comics criticism is still young and scrawny," as Douglas Wolk has written, then comics scholars have been bulking up in a number of ways, but our general regimen is the narrative. This emphasis may owe to comics studies' emergence from the fields of English and film studies, both of which are highly invested in narrative; the terminology of film has been useful if inadequate in describing how comics work. And then there's semiotics. Since the publication of Will Eisner's Comics and Sequential Art and Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, greater attention has been paid by cartoonists, critics, and scholars to the formal dissection of comics, a venture wrapped into the larger expedition that is the burgeoning discipline of comics studies. The influential work of Thierry Groensteen in The System of Comics and, recently, Narration and Comics, has truly pushed formalist comics studies into the realm of semiotics, which has helped to reestablish the importance of the image. This is seen as a corrective to the past emphasis on comics as literature, which I'm not sure is entirely fair, but that seems to be the thrust of things. Oddly, though, this work in semiotics has focused almost exclusively on narrative comics. Most comics are narratives, but then again, we used to say that most visual art was either painting, sculpture, or architecture. If we're going to define what comics are, then we have to account for non-narrative work. Poem comics are comics.

4.

My use of the word "lingering" has no specific source, though I believe Scott McCloud uses it once, in a similar sense, in Understanding Comics. By lingering I simply mean the meditative action of the eye and the reader's thinking upon a word or image.

"Profluent" does have a source: the novelist John Gardner and his book, The Art of Fiction. As far as I can tell, Gardner was the first person to use the term "profluence" in centuries; according to dubious internet sources, we may attribute the word's invention to Sir Henry Wotton, who was one of those rich people in the early 1600s lucky enough to sit for a portrait. Bully for him! Gardner's application of the word to narrative has become widespread in creative writing programs (of which, full disclosure, I am a product). He describes profluence as the narrative quality of forward motion, "our sense," he writes in wonderfully plain language, "that we're 'getting somewhere.'" His definition, as one might expect, hinges on narrative qualities of causality, resolution or "logical exhaustion," but also, crucially, upon sequence.

(By the way, as far as I know, nobody painted a portrait of John Gardner. This is a minor crime, but a crime nonetheless.)

The clear problem in my definition of profluent lingering is that poem comics infrequently derive their momentum from narrative, and yet they certainly possess momentum. Is this the same as profluence? (And of course there are narrative poems, but one crisis of definition at a time, please.) It's also not accurate to say that poem comics only linger due to their frequent emphasis on economy and the building of a singular mood or even image, since they still work in a read sequence, swelling and relenting, breathing in and out more noticeably than a long narrative. Because of that economy, a poem comic's profluence may be abrupt but profound.

5.

So I try it out, reading "How It Is," originally published in The Brooklyn Rail, for profluent lingering. In panel 1, the narrator is telling stories. Or are these three different women? Are these women? The piece is already ambiguous, disjointed but unified as verbal and visual speech. Each word balloon is perhaps the equivalent of two lines, ie. short stanzas. This is the only panel with a frame. Stasis and momentum balance as we try to piece together each image. Note how the consistent line work holds everything together while the postures resist an easy coherence.

In panel 2, there's our Jesus. Entirely wordless, this panel begins a very long pause, a gap—but only from a word-centric point of view. It's tempting to see this sequence (into the next tier) as a stanza break, but no stanza break is this dramatic in verbal poetry, and the image(s) of the sequence are still speaking. White space sets everything off: not just the image in the panel, but everything around it, creating a context. We linger.

Panel 3 bleeds into panel 4 by way of the electric cord. We don't linger on this image for long; there's nothing much to look at, just a boring desk. It's less of a pause than panel 2, so the tempo is picking up.

Then the tricky part. Since the final word balloon in panel 1 is about midway down the field of the comic, finishes a left-to-right sequence, and trails off into ellipses, when I originally read the poem comic, I temporarily jumped down to the completion of the line which sits on the left, invisible border of panel 4 in the second tier. And so everything I've said about profluence and lingering in panel 2 and panel 3 is potentially erased. Our eyes might skip all over the poem comic, back to the beginning, or just back to Jesus. Panel 4, in and of itself, increases the sense of profluence because of the dialogue, but that's disjointed, too. (All of this suits so well what reads like a confession of drug abuse, by the way.)

Panel 5 jarringly stops the poem. It has a radically different context, like panel 2 above it, which is perhaps fitting since it's the last panel. We're left to linger on this panel with nothing else to read.

6.

Gardner's usage of the term is clearly centered on prose narrative, but because I'm applying "profluence" to the alchemy of comics which must include the visual, and thus already stretching Gardner's usage, why not stretch it a little further? It's not difficult to apply that sense of "getting somewhere" to poem comics since poems are propelled by virtue of being words in sequence. Let me risk speaking in broad terms. Instead of what Gardner described as the "causally-related events" of narrative which end in resolution or no-resolution, profluence in a poem is the developing cohesion of elements that are associatively related. As we read, these fragments arrive into their coherence as a revelation of thought, feeling, event(s), mood, and so forth. They may resolve, or they may dissolve.

In her recent, illuminating, and appropriately-titled-for-our-purposes book Narrative Structure in Comics: Making Sense of Fragments, Barbara Postema explores various perspectives on the implied narrative within single images. These include Rudolf Arnheim's distinction between the "pictorial image" and "literary image," which might be helpful to consider in regards to poem comics and a different kind of profluence than what Gardner had in mind. For Arnheim, a literary image, comprised of words, "grows through…accretion by amendment. Each word, each statement is amended by the next into something closer to the intended total meaning. This build-up through the stepwise change of the image animates the literary medium." This is what I mean by arriving at coherence, which applies to poetry as much as it could be applied to prose regardless of narrative. (It could also be applied to prose poems. Oh God, what do we do about prose-poem comics? Deep breath.) What I have borrowed from Gardner, "profluence," can be equated with accretion or "stepwise change," which loosens the grip of narrative a bit. In any comic, the literary image develops in a sequence on a spatial plane and "animates" the comic as it's read.

We might be inclined to equate the generally economical poem comic with Arnheim's pictorial image which he says "presents itself whole, in simultaneity." The pictorial, simultaneous presentation of a relatively short verbal poem might not convey much significant meaning, but the space a poem occupies and how it occupies that space do convey some meaning. In Dadaist and concrete poems, space matters a great deal, but doesn't it matter, too, in "Howl" or "The Red Wheelbarrow"? Poems do present themselves in a pictorial fashion, though we might argue that this fashion ultimately supports the literary image.

A poem comic, however, combines pictorial and literary images; it develops through individual static images, "accretion by amendment," and spatial, sequential arrangement on the page. Just as we would never exclude poetry from literature, we shouldn't exclude poem comics from the literary image by confusing "literary" for "words-only" or "narrative." And if the literary image can be equated with profluence, then poem comics can possess profluence. What Arnheim describes as wholeness and simultaneity is similar to what I mean by "lingering." While poem comics may often lean toward a prominence of the pictorial, toward a sense of simultaneity and lingering, their sequentiality aligns them closely with the literary image. As with profluence and lingering, the pictorial and literary impulses are often in tension within a poem comic.

And if you've made it through all that, go buy yourself a beer. You deserve it.

7.

To borrow a phrase that business people keep saying more and more every day, I'd like to "stick a pin" in Arnheim's notion of the "pictorial image" as a simultaneous one. Only the most simplistic image—a smiley face, for instance—seems capable of communicating its full meaning in a truly simultaneous fashion. I think we do perceive the whole in what I'll describe below as an initial encounter with the image: a snapshot. While this preliminary glance informs our interpretation, it does so tentatively; it's only part of the meaning, and we recognize it as such before we begin to perceive parts of the whole. Can we really see all the components of single image simultaneously, especially in a comic? What I find appealing about the term "lingering" is its very lightly implied sense of focus-in-motion, that is, the freedom of the eye to move over a small visual field while maintaining the sense of being still. Is that the same as a perception of simultaneity? I'm not convinced that it is.

8.

Simultaneity and accretion; lingering and profluence—these refer to dimensions of space and time as we engage with the artwork. As Postema, Groensteen, Neil Cohn in The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images, and many others have pointed out, we are acutely aware of these dimensions when we read comics not just because a comic employs both, but because we control our engagement with them.

Before we go any further, let's review:

a) Profluence and lingering in comics work in tandem; they can be distinguished, but not separated; where there is one, there is the other, even as what might seem like an absence; thus time and space are always yapping at each other like toy dogs;

b) Setting aside my squabbles with the concept of simultaneity, in a comic, lingering is never only a concern of space; it also involves the feeling of time's suspension and the awareness of its passing; likewise, profluence is never only a concern of time and its passing since it's created in space by static images and words; the toy dogs are leashed to one another;

c) To repeat: profluence and lingering work by a comic's verbal and the visual elements—that is, by the words, the images, and the spatial field of the panels and the pages; I don't have anything more to say about toy dogs;

d) Because of the above, the dynamic of profluent lingering in a comic always contributes to the accretion of meaning, which is to say that, by Arnehim's terms, how a literary image is formed through the accretion of multiple pictorial images affects our interpretation.

9.

The relative economy of a poem comic, even a long-ish poem comic, influences our expectations about how we'll engage with space and time—and thus how we'll look for meaning in the work—even before we begin reading it. This is the snapshot I mentioned earlier. Condensed time and space energize the heightened language of poetry; in fact, you might say they set the stage for that heightened language to work, asking the reader to linger over words, to chew on them slowly, savoring the taste, and also prepare for an intense ride, a brief, maybe jagged, maybe graceful profluence. Smaller gestures mean more, both verbally and visually. The gaps mean more, too, those between panels and pages. In a poem comic, what's left out is as important as it is in poetry. As often happens in Stone's work—and she's essentially said what I just wrote, that the picture in a poem comic shouldn't redundantly illustrate what the text is already saying—the images voice what the words omit and the words voice what the images omit.

As always, each work makes its own unique demands.

10.

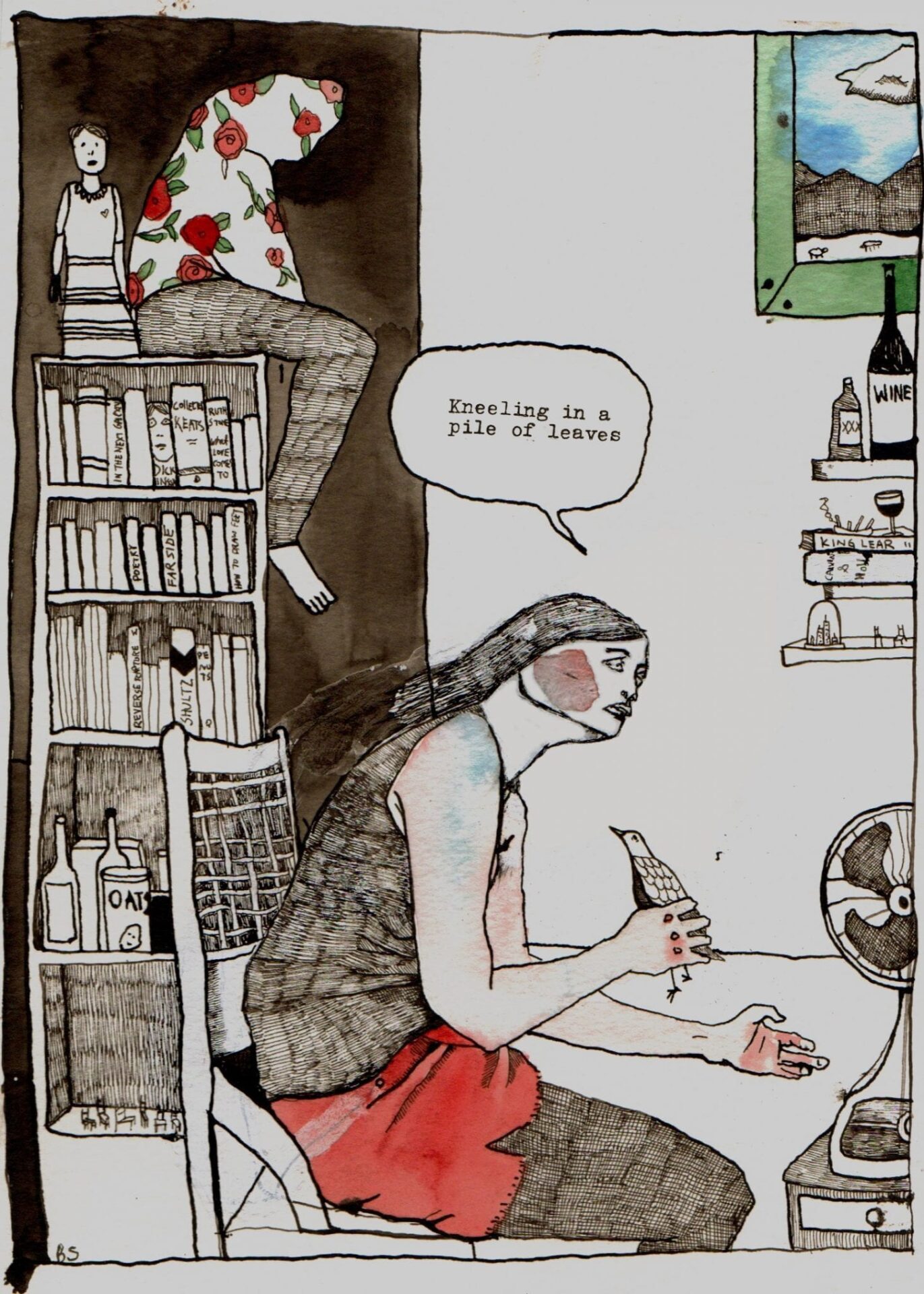

Stone's "Kneeling in a Pile of Leaves," which appeared in Plume, is a "lingering" kind of poem comic. It consists of two pages, each entirely comprised of a single panel, each panel occupied by a single image. (There are multiple small images in each conglomerate image, but I feel a semiotic headache coming on, so we'll save that discussion for another occasion.)

In the first panel, a melancholy woman holds a bird in her right hand as if she's about to use it to cut her left wrist. Sitting on top of the bookshelf behind the woman is a figure in full profile—a person? a giant doll?—with its shirt pulled over its head. Next to that figure stands what does more recognizably look like a doll. The melancholy woman says, "Kneeling in a/pile of leaves," a statement which we discover is continued in the next panel/page: "waiting to be/taken over/by your brain." In this second image, the reader faces a figure wearing a cross-hatched suit jacket and a diving helmet who is standing behind what may be an old woman. The Diving-Helmet Head figure seems to be reaching its hands toward the woman's neck. The woman appears calm, stoic, and glances away to the reader's right, perhaps off the page, or perhaps at the hand coming into her line of vision.

11.

We linger over this poem comic as a result of its brevity, true, but two other elements are at work. The size of each panel more explicitly suggests the static quality of a standalone image, encouraging us to read the two images as we would two single illustrations, paintings, or photographs. By assuming the fullness of the page, each panel and thus each image contained within assumes a weight of meaning. The images are hardly contained; they're everything. The second element is the visual information within each panel: a vintage electric fan and a can of oats; the blush or blemish on the woman's cheek; the titles of the books on the shelves, which include a collection of Keats, The Far Side, Schultz, and What Love Comes To by Bianca Stone's grandmother, the poet Ruth Stone.

I haven't even mentioned the rose patterns on the old woman's shirt in the second panel! Or the way that the broken-necked posture of the figure in the diving helmet makes it seem even more macabre! The tedious work of describing these images in words demonstrates the relative immediacy and grace of the image, particularly in how we first encounter it: the snapshot that occurs when we find in the image some kind of immediate if temporary focus and an awareness of the detail around it. The next step is an exploration of the image's detail, its objects, its text, which is the moment when lingering really begins. We aren't "getting somewhere" other than here, and yet we sense the need to move on eventually. In a comic which is composed of even less visual information—a panel in a John Porcellino or Katie Skelly comic is likely a good example—there's simply less for our eyes and brain to study, and so we move on sooner.

The sense of lingering works differently in the two panels, though, and is affected by the image and the words in each. In panel one, my attention is drawn first to the blushing, melancholy woman—actually, it's drawn right to that pinkish blush/blemish. Then the words. This panel takes longer to read because there's more to explore. In the second panel, the image is fairly stark, and so the final words stand out. If I were to visualize how I read the two pages, the first page would be a vortex spinning out from the center, and the second would be something more succinct—a block, perhaps, more like Arnheim's simultaneous pictorial image, but still not the same thing.

12.

In "Kneeling in a Pile of Leaves," the words alone seem to create what slight sense of profluence there is. So distinct from each other and appearing to have no causality, the panels/pages produce a shudder, a hard-as-nails juxtaposition. Meanwhile, the first two lines of the poem comic's words are separated from the last three lines which occur on the second page. (Compared to "How It Is," the verbal text here does seem more recognizable as poetry, especially since it's rendered in a typewriter font.) This final trio of lines is broken into a two-line speech bubble emanating from Diving-Helmet Head and the floating, uncontained final line; to make full sense of the text's meaning, we have to cross the gap between the two panels, which feels like a very large gap indeed because the two panels are pages. (In a words-only poem, a stanza break would accomplish a similar but far less dramatic crossing.) With only one transition across a gap, but a transition that's jarring, the profluence in "Kneeling in a Pile of Leaves" is minimal. It enforces the sense that this is an abrupt occasion of speech, a blurting out of unplanned and intimate thought, whereas "How It Is" feels relatively crafted, planned so as to seem unplanned.

13.

"Kneeling in a Pile of Leaves" is a mystery, though not as ambiguous as "How It Is." Again there are multiple selves and speakers whose words are shared. Following the words from one panel to the next, do we imagine that the melancholy woman has become Diving-Helmet Head? Who sits on the top of the bookshelf? Who is kneeling? In one reading, the poem emanates foreboding, an eventual grotesque reshaping of the mind that matches the slightly misshapen and surreal figuration. Hues of red link the young, melancholy woman, plaintive as an apostle, to the older woman who sits unnerved in her chair in the second panel, so is this the same woman in each panel, transformed by time, or two different women?

My reading of this poem comic hinges on the studiousness created by the sense of lingering. On my initial encounter, I didn't notice the inclusion of the book titles, but the more I looked, the more relevant they became, scattered as they are between the historically high art of poetry and low art of comics. Already their inclusion on the bookshelf alludes to Bianca Stone's influences, but the inclusion of Ruth Stone's Pulitzer Prize-nominated and final collection of poems, What Love Comes To, published two years before her death in 2011—well, this anchors the implied conflict between the high and low, joins and resolves them into the personal, and possibly argues for the importance of family over culture. It's impossible now for me to not think of the woman in the second panel as Ruth Stone; it's also impossible for me to not think of her as my own grandmother, who in her late years wore a quilt-like nightgown adorned with a similar rose pattern.

Speaking broadly, the lingering impulse in "Kneeling" creates the perhaps more expected poetic qualities of meditation and ambiguity, while the blunt profluence cuts against any sentimentality.

14.

A reworked-in-progress definition of profluent lingering, for now: "…the result of the variable tensions between a sense of progression and a quality of stillness, both of which manifest in multiple media—pages, panels, images and words—that are arranged sequentially. We might also think of profluent lingering as the constant negotiation that goes on in the reader's mind between the forward momentum of sequential words and images, and the temporary stasis of looking at a single word or image."

15.

The point of a concept like profluent lingering is to give us more insight into how a comic works and how its working influences our interpretation. As a community, we're not talking enough about what individual poem comics mean. Instead, we seem to be mainly talking about poem comics in terms of clout. Which is dominant, poetry or comics? The literary or the visual? High culture or low culture? The currents of power and prestige lurk under the surface of these arguments, whether it's in Derik Badman's response on The Hooded Utilitarian to Steven Surdiacourt's "Graphic Poetry: an (im)possible form?" at Comics Forum from June 2012 and an interview with Bianca Stone at The Comics Journal that August, or in Hilary Chute's short essay "Secret Labor" at Poetry magazine in July 2013, which occasioned a leery response from the Utilitarian's editor Noah Berlatsky in The Atlantic. The issue can be summed up briskly: a literary contingent of poets and comics scholars is intrigued by poetry comics while a contingent of cartoonists and comics scholars is worried that said literary folks are co-opting comics for the purposes of legitimization and cultural-aesthetic influence. What "literary" means seems to be taken for granted on all sides.

It's amusing and frustrating to watch this play out; every claim reveals only more anxiety or confusion about cultural and aesthetic power. Berlatsky seems to be criticizing Chute's narrow view of comics as literature, but then criticizes poetry as an elitist art form, "an ivory tower phenomena of painful and infuriating insularity." Nobody reads that kind of poetry, he argues, but the poetry we do read, what he describes as "pop poetry—song lyrics, rap lyrics, children's book doggerel," is populist. Because, I guess, all song lyrics are the same? Meanwhile, Chute offers some intriguing ways that comics might be poetic, but as Berlatsky points out, she champions the literary and narrative work of Alison Bechdel and Joe Sacco and says nothing about poem comics. (If, as she writes, "the most fruitful analogy to comics might be poetry," then I'd like to see that tested on old Heathcliff comics.) Badman seems correct when he criticizes Surdiacourt and Stone for not being more familiar with cartoonists who make poem comics—people like himself—but he slips into a self-pitying defensive posture, at one point writing, "There are a bunch of us out here, Bianca." Ultimately this all starts to feel restrictive and upsetting, like watching C-SPAN, when the problem, if it is a problem, is the comic art form's Montana Big Sky-ness, its enormity.

Some of these conversations seem to have had a positive effect, though. Stone and a group of co-conspirators have published a few issues of Ink Brick: A Journal of Comics Poetix. (Another term!) In spring 2014, Badman and Stone joined Warren Craghead (whose work deserves a critical essay or three of its own), Sarah Ferrick, and Andrew White for an exhibit of poem comics at the Craddock-Terry Gallery in Lynchburg, Virginia.

On the critical side of the coin, we need to write more about poetry comics, or comics poems, or poem comix, or whatever the hell we're going to call them. More about how the form of the work influences our interpretation. More about cartoonist-poets like the ones I've mentioned above. More about John Hankiewicz, Aidan Koch, and Anders Nilsen. I'm not sure if Marnie Galloway's In the Sounds and the Seas is a long poem comic or not, but someone should write about it. Let's have more, not less.