The Comics Journal #208 (November 1998)

Richard Sala worries that you may not understand his work. And he’s right to worry. His preoccupation with genre archetypes has made it easy to miss the meaning in his work.

Certainly anyone halfway familiar with alternative comics of the last 15 years can describe the superficial elements of Sala’s oeuvre. Sardonic stories of duplicity, doppelgangers and murder. Twisted streets from German Expressionism, vamps and no-goodniks out of hard-boiled pulps, sinister glee a la Edward Gorey and Charles Addams. An evocative style that has evolved from a new wave scratch to a supple illustrators signature.

After self-publishing a magazine-sized comic, Night Drive, in 1984, Sala became “the king of the bad anthologies,” as he puts it himself. Not all of them were rubbish, of course, and they gave him the space to grow in three- and four-page spurts. After his “debut” in Raw, he appeared in Prime Cuts, Snarf, Blab!, Buzz, Twist, Street Music, Rip-Off Comix, Taboo, Escape, Deadline USA, Drawn & Quarterly and (amazingly) others. He and Charles Burns even found their way into a mainstream anthology, MTV’s animation showcase Liquid Television, which included Sala’s Invisible Hands. This was not, however, his ticket to success, and he returned to comics, producing a single issue of a comic called Thirteen O’Clock for Dark Horse in 1992.

Meanwhile, Sala found greater success as a magazine illustrator, with work in high-profile places such as Entertainment Weekly. His short comics-collected in the Kitchen Sink volumes Hypnotic Tales (1992) and Black Cat Crossing (1993) — began to look like a way for Sala to indulge his obvious obsession with horror noir archetypes.

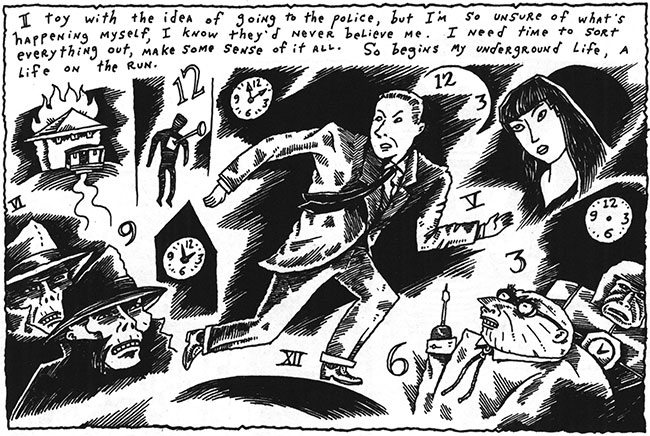

Those archetypes also dominated his small book The Ghastly Ones and his magnum opus to date, The Chuckling Whatsit, serialized over 17 issues of Fantagraphics’ Zero Zero. A cliffhanger dense with malevolent motives and grotesque revelations, Whatsit extends the quests that dominate Sala’s work to epic proportions.

In doing so, Whatsit suggests that there is more to Sala’s play with genre than just, well, a chuckle. Sala is, in fact, much more aware of the symbolism and meaning in his work than most cartoonists — not for nothing is he married to a psychologist. All that secluded violence, all those masks, all those baffled heroes waking from dazes to find that they’ve joined secret cabals, killed loved ones, or simply forgotten their girlfriend’s birthday — Sala can pick it all apart with the adroitness of the sharpest Journal critic. There’s always a Big Secret at the heart of Sala’s stories, and his endless variations on this theme suggest it has more resonance for him than simply a nifty plot hook or MacGuffin.

The interview opens a door on that meaning. Given Sala’s new series Evil Eye, there’s no better time to address his work in a more serious light.

What this interview may not fully reveal is Sala’s humility, so strong it borders on a lack of self-esteem. An articulate and perceptive artist, he repeatedly admonished himself for not being clearer, now and then suggesting, “We should just start over.” Nonetheless, he was any thing but removed or paranoid - a warmer, more engaging interviewee would be hard to find. (It no doubt helped that we share fond memories of an Arizona children’s program, Wallace and Ladmo.)

This interview was conducted on May 31,1998, in Sala’s longtime Berkeley home. It was edited by myself and Sala.

THE COLLAGE EFFECT

DARCY SULLIVAN: Let’s start now, as we’re looking at some of your childhood photos. I love this one of some of your prized possessions on your bed — comics, books, photos. But why are there dollar bills on top of the comic books?

RICHARD SALA: Maybe it was some sort of collage thing I was going for, I would have to go back and commune with my 1969 psyche to remember why I took a picture of that stuff.

SULLIVAN: So when did you move to Arizona? Because you were born in Chicago.

SALA: I was actually born right here in the Bay Area. At Kaiser Hospital in Oakland. Our family moved to Chicago when I was three and then to Arizona when I was in sixth grade. I remember being really happy in Chicago. And then Arizona was total culture shock — or lack-of-culture shock — because unless you liked cowboy art you couldn’t find much culture there. I have very affectionate memories of Chicago. I remember being totally absorbed by the museums — the mummies, dinosaur skeletons and caveman dioramas. At that time the monster craze was in full swing, I have photos of me in my Wolfman T-shirt and my Aurora monster models.

SULLIVAN: Dan Clowes told me that you ordered everything from Captain Company [a merchandise company advertised in Warren magazines like Famous Monsters] that they ever sold.

SALA: Well, jeez, no, not everything. Dan exaggerates.

SULLIVAN : When did you start collecting all this stuff?

SALA: I probably started collecting or rather — accumulating — really early. Both my mom and my dad were collectors. In fact, my dad was a professional collector. He restored antique clocks. I grew up going to flea markets and antique stores, and talking to dealers. When I was a teenager, I began really loathing the whole collecting thing, and by the time I was an adult, I got rid of almost everything. But there was some stuff I couldn’t bear to get rid of, and that I put in storage. It was only after I was in my 30s that I wrote to my mom, who’s still in Arizona, and had her send me the stuff I’d saved.

SULLIVAN: She still had it?

SALA: I saved it in boxes and told her, “Please don’t throw this away.” She owns her own house in Tempe, Arizona.

SULLIVAN: That’s where I lived as a boy.

SALA: I lived there for awhile, too. She may have gotten rid of some stuff. I had a scrapbook of all the monster ads from newspapers, like Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and Dr. Phibes. I'd cut them out and tape them in the scrapbook. That appears to be gone. But I have my scrapbooks of Dick Tracy and Li’I Abner comic strips that I cut and saved as a kid.

One of the reasons I had my mom send stuff out was that I was trying to finance my life. I knew that a lot of the stuff I had as a kid was now valuable. At the time, I just needed to live and I didn’t care about collecting. I was living a pretty spartan life, believe it or not. I know it’s hard to believe now — I’ve pretty much gone back to being a packrat again.

AN ITALIAN IN ARIZONA

SULLIVAN: OK, now let’s start at the beginning.

SALA: My mother and father met at U.C. Berkeley, right down the street from where I live now. My dad was the son of Sicilian immigrants. He was a janitor at Berkeley. My mom was a student who came from a WASPy Protestant stock and both her younger sisters had married well-to-do men. I suppose when they got married people said it would never work, and of course, it didn’t. I was born in 1955.

My mother was from the Chicago area, so after a few years in the Bay Area, my father got work with my mother’s father’s company in Chicago, so we all moved to West Chicago. I spent all my formative years there. The first comics I remember reading were the Jack Kirby/Steve Ditko Tales to Astonish, and all that Atlas monster stuff. I just loved those. You read them now and it’s like reading the same story over and over again. But for little kids, they were great,

I remember the whole Marvel renaissance. I bought all those early copies. I can still see my copy of Amazing Fantasy #15 in the toy box. In pieces. It was sitting there for years. I was always more a Marvel guy than a DC guy. I remember buying the old Batman 80-page giants. I liked those, because I liked the old-time Batman style. The new Batman stuff didn’t appeal to me at all.

When we finally had to move from Chicago to Arizona, it was partly my fault, because I had asthma. I was kind of a sickly kid. At that time — in ’66 — Arizona was being advertised as a really healthy place to live. Of course, now Phoenix is a valley filled with smog. But at the rime, it was considered to have really fresh air, and there were all these advertisements on TV: “Send your sinuses to Arizona.” When we moved, I took all my comics and taped them up in a dresser.

My mom had said, “Throw them all away because we’re moving, we need to travel light,” but I didn’t want get rid of them. So I taped them all up in a dresser, and of course when the dresser got to Arizona, they weren’t there.

SULLIVAN: They weren’t there?

SALA: No. I told my mom, and she said, “Well, the moving men probably opened it up and just tossed them.” I remember that the moving men lost a lot of our stuff at the time. My dad had all these great antiques — he had two old manual phonographs with the big horns, and we only got one. I still remember when I was closing that drawer, the very first Doctor Doom issue of Fantastic Four (#5) was sitting on the top of the pile, because that was my favorite. I loved Doctor Doom. And I remember thinking, “OK, I’ll see you in Arizona!” And he never made it. That was one of those things that probably turns you into an obsessive collector. Because you spend the rest of your life trying to find it. Back then there were no comic book stores and no place to find back issues. In fact, I had a recurring dream that I would walk into a store and they sold nothing but comic books — years before any comic stores even opened.

Another thing that was a huge influence on my childhood was the huge nostalgia craze for the ’30s that ran throughout the ’60s. A lot of elements of ’30s culture in my work have come secondhand because of that craze. Everybody had posters of the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, and Frankenstein on their walls. There was Flash Gordon and King Kong everywhere, and everything was campy and pop-art. But of course as a little kid, I didn’t really get camp. It just seemed like everyone thought that ’30s culture was fun and cool.

SULLIVAN: You didn’t know what was new and what was old.

SALA: Right. I’d get up really early and watch the Flash Gordon serials on Chicago TV and take them really serious. They were very melodramatic and earnest, perfect for a little kid. It wasn’t until later I found out that people were laughing at them. I was one of the many kids in my generation who thought the Batman TV series was dead serious.

The Great Comic Book Heroes was one of the first big books I ever owned beyond, you know, Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak books. That was a massive influence on me. I never got tired of looking at the really crudely drawn Golden Age comics. I just loved that aesthetic — I love seeing the struggle to work something out.

I also have a half-brother who’s much older than me. He had cool hot rod magazines, and issues of Famous Monsters. Dan and I talk about this, the older brother syndrome. If there’s an older brother that has cool stuff, the younger kid often gets hooked.

SULLIVAN: Now, of your “whole” siblings, are you the oldest?

SALA: I’m the middle child. My other brother is two years older than me, and my sister is three years younger than me. They both still live in Arizona, too.

SULLIVAN: You’re the only one who moved away from Arizona?

SALA: Yeah. I had to get away. I never really took to Arizona. In Chicago, I was pretty well-adjusted, as I recall. We lived on this great old street with lots of really old houses, with a very mysterious kind of feeling. I remember bats flying around the school during the fall, and things like that. We had a house filled with antiques — grandfather clocks, lots of old clocks, always chiming and ticking away. There was an old woman down the street who all the kids thought was a witch. We had a player piano and my dad had a workshop for making lead soldiers out of vintage molds.

And then I moved to Arizona, and it’s all sunny and hot and I’m paler than every kid around. Everybody’s healthy and blond, and they’re all into sports. The main exercise I got was running from one patch of shade to another. There were scary-looking guys with bolo ties, buzz cuts, and cowboy boots who had rifle racks in their pick-up trucks. This is the late ’60s. I never fit in. I think that’s the beginning of my whole outsider mentality. Shortly afterwards, when I was in high school, I discovered Kafka, and his stories really spoke to me personally. I understood the feeling of being in a place where you’re different from anyone else.

I grew up hearing my mom and dad talk about the Bay Area. It always seemed like a cool place. So it was always somewhere in the back of my mind to return. When I got accepted into art school in Oakland I just came back and never left.

SULLIVAN: Is Sala your full name, or your dad’s full name?

SALA: Yeah, it is. It means “hall” in Italian. Although I’ve seen translations that say “dining room table.” Since the meaning of Richard is “ruler,” I like to think that my full name means “ruler of the dining room table.”

TOO HOT FOR ENGLISH

SULLIVAN: You were in Arizona for a few years, because you went to —

SALA: Very many years, actually. An eternity. I did go to a pretty liberal high school though. In your senior year you had electives, which was really good, because they let us read like crazy, and I loved to read. I’m not sure when that started — maybe the seventh or eighth grade. I discovered the reprints of Doc Savage, The Shadow, and The Spider (more of that ’30s culture), and I devoured them. I could read them in a couple of afternoons, and sometimes even in one sitting. Anyway, as a senior you had electives, and one of the classes was Developmental Reading, where you could sit and read all the time. You would count how many books you read and make a little report. I read things like Catch-22, all the Kafka books, the Salinger stuff, Aldous Huxley. At that time Hermann Hesse and Aldous Huxley were being released in paperback with groovy Milton Glaser covers. I remember writing reports on — you know — the poetry of Leonard Cohen and so on. Another student there was Sandra Bernhard, the actress. She was a year younger than me, and I remember seeing her around. She was another horribly miserable outcast.

SULLIVAN: What was the name of the school?

SALA: Saguaro High. About 10 years ago, I was asking somebody about it, because I never was invited to any reunions or anything, and they said, “Oh yeah, it was overrun by people taking drugs, and it’s no longer there.” I have no idea whether that’s true or not.

After high school, I went to Arizona State University because I didn’t have any money to do anything else at the time. I was resigned to living there. I had a girlfriend and we lived together — and I still had no idea what I was going to do with my life.

My dad was a frustrated cartoonist, I think. I remember him drawing when I was really little. I remember sitting around the table with cousins and stuff, and them all being really impressed that my dad could draw. So I started drawing at a real early age. One of my earliest memories is of my kindergarten teacher complimenting a drawing of a tree I’d done. That seems to have been an important moment. So I drew and drew — I created my own comics. Dan and I have shown each other our excruciatingly embarrassing casts of comic books characters we created as kids. Naturally I went on to take art in high school. The problem was that I had the same damn art teacher every year. And he was a really boring, boring guy. He wasn’t really a bad teacher, just mediocre, but it shows how a mediocre teacher can really kill interest in something. I lost interest in art. I was reading a lot, and I decided that I wanted to be a writer. So by the time I was a senior in high school, I wasn’t even interested in art, even though when I was a junior I was winning these little competitions that my art teacher would enter me in. But I just lost interest. I was reading things like Richard Brautigan, Kurt Vonnegut and Donald Barthelme. I loved that kind of stuff. Of course, a lot of it has not held up very well over the years, but at the time it seemed really fresh and innovative. So when I went to college, I majored in English. I wanted to be a writer.

I was living with my high school sweetheart who was really stable. When I started college, the whole feeling of being an outsider crept up on me again. Taking English classes in lecture rooms, I didn’t meet anybody. A lot of my friends from high school didn’t go to college or went out of state. I was becoming increasingly miserable, because I still didn’t know what I was going to do with my life. I checked out some art classes, but at ASU you had to be an art major to go on to more than one or two classes. So I decided to change my major. I thought, “I probably have just as much chance of making a living being an artist as I have being a writer.” One of the other problems was that I loved writing, but even my best friends wouldn’t read anything I wrote. It was impossible to get feedback!

SULLIVAN: I think all writers have that problem.

SALA: You would lend people a short story or a manuscript, you say, “Hey, tell me what you think?” And two weeks later, they’d go, “Yeah, I haven’t got a chance to read it yet.”

SULLIVAN: It’s five hundred words —

SALA: Nobody’s interested in reading amateur unpublished stuff.

SULLIVAN: But you can get them to look at your pictures.

SALA: Well, that’s more immediate. And that wasn’t lost on me, believe me. I liked the immediate reaction. I’d go into these art classes, I’d see all these cute girls wandering around. This is Arizona, it’s warm, and people are wearing shorts —

SULLIVAN: The whole time.

SALA: And I’m just like — “Damn! I’m sitting in these horrible lecture rooms with all these boring people talking about Shakespeare. What am I doing?” So I changed my major, I took art classes, and I felt renewed again. I had fun in art school. I don’t recommend it for people necessarily, it’s not even slightly practical, but had a lot of fun. You have a great time sitting in coffee shops passionately discussing Surrealism, going to art openings for the free snacks, or doing all-nighters in the print-making department while blasting music.

When I think back on my 20s, I don’t think I started living as a serious person in the real world until I was over 30. I mean, in art school I did really develop as an artist and I did some good work, but still, I think of my years in art school and in college as playing. People who know me now wonder why I never take vacations, I never go anywhere, I’m always working. I tell them that the whole decade of my 20s was one long vacation. I got it out of my system. I didn’t really grasp it then but I realize now that I was also very neurotic. Those feelings of being an outsider never really left me and I was grappling with anxiety and depression.

SULLIVAN: Were you doing illustrations during this period?

SALA: Yeah. When I was at ASU, a friend of mine was president of the Cultural Affairs Board. One good thing about small scenes like Tempe is when you go to the weird little art shows, movies, or parties, you keep running into the same handful of people and eventually get to know each other. This is right before the years that punk really hit, in the late ’70s, and it was certainly before it hit Arizona. We were sort of proto-punks, and we founded this thing called Art Brut Graphics — we didn’t really found it, we just named it that. We did all the posters and movie schedules and stuff for the Cultural Affairs Board. Mostly my stuff would appear in the State Press, which was the newspaper for ASU. I started doing work for some of the local weeklies as well. The people at The New Times in Phoenix are my heroes. The New Times gets a bad rap these days because they’re a chain alternative newspaper. But I was there when those guys were starting, and to be an alternative newspaper in Phoenix in the ’70s was like putting a target on your back.

SULLIVAN: Didn’t they have Bob Boze Bell?

SALA: Bob Boze Bell was one of the many art directors I worked for. I often worked with the editor, Michael Lacey. The third cover I did for them won the graphic arts award for the best illustrated cover of the year in Arizona. There was a banquet for the Arizona journalism awards with all these conservative businessmen, and they were showing the slides of the winners. Michael Lacey told me with great pride that when my cover went up, there were a lot of dropped forks in the room. I mention winning that award because in a way it showed me that I was on the right path, and until that point, I never really knew that I was.

FAMILY MATTERS

SALA: Like a lot of people, when I was younger, I always thought of my family as pretty normal, boring even. It wasn’t until I had the hindsight of an adult, that I virtually slapped my head in disbelief at how fucked up we were. I won’t go into most of it, but I realize now that it is pertinent to the discussion of my work to say that my dad had a horrible temper. He threw lots of fits of irrational rage, where you never knew what he was angry about. He’d just go insane and smash things, and terrorize us kids. I see now, looking back, that my whole interest in the irrationality of violence stems from this childhood.

I remember my dad, once, because he was frustrated about something in his life, I guess, walking over to my brother’s little Yogi Bear guitar and just smashing it with one stomp of his foot. Here was a little musical toy, something that gave pleasure and joy, and suddenly this hurricane of anger would come into the room and smash it, and we would all be cowering and hiding. And, you know, in those days, spanking and hitting kids wasn’t frowned upon. In fact, I remember teachers hitting kids all the time!

SULLIVAN: Was it temperamental? I mean, did your dad have chemical problems or was he drinking?

SALA: He didn’t have the excuse of being an alcoholic. He was very insecure. He had lots of insecurities, and I think he felt really powerless. His life hadn’t gone in the direction he wanted it to, or whatever — who knows what? I haven’t analyzed his anger that much. I basically wrote him off. I’ve been estranged from him for many, many years. He’s still alive somewhere. He’s in his 80s.

SULLIVAN: Did you and your brother and sister bond over this?

SALA: I think so, but there’s a little bit of that whole survivor guilt thing, and also that — what do the veterans have? Post-traumatic stress syndrome.

There were lots of horrible arguments. I mean, it was the ’60s, too, so definitely there was a generation gap that played into it. I was into late ’60s youth culture and my dad didn’t understand that. You dreaded every dinner time, because you had to get together and sit at the dinner table. I think I was 13 or 14 when my parents got divorced and suddenly there was a huge relief in the house. I didn’t realize how horrible of a scene it was until it was over. Then it really felt like freedom. Of course, we still had to go through the legal bullshit of weekend visits and so on. My siblings and I hated him, but we had to see him on weekends to go to movies or meet his new family. Eventually he stopped paying child support, so we were like, “Why the fuck do we have to pretend to like him?” My one real regret is that, although I was rude to him, I never really told him to go fuck himself to his face. You know — really big man, terrorizing little kids.

SPOILED BY ART SCHOOL

SULLIVAN: You moved out to the Bay Area after you went to ASU?

SALA: Yeah. I got accepted at Mills College in Oakland. It’s a woman’s college but on the graduate level, it’s been co-ed for decades, and it’s a great school for graduate art students because it’s very small, and you get your own studio, and the core faculty that teach there are great. My painting teacher at the time — I was her teaching assistant — was Jay DeFeo, who was a Bay Area legend, a beatnik abstract-expressionist. There was another guy there, Ron Nagle, who was also a bit of a legend, an amazing ceramicist and musician. But of course, art school is a cult. It separates you from the real world and really builds up your ego —

SULLIVAN: It builds up your ego?

SALA: Yeah. When you’re in art school, you think you’re terrific. If you’re good at what you’re doing, you feel you're going to go out and take over the world. And probably the people whose ego isn’t built up during art school are the ones who are the most successful, because —

SULLIVAN: They try harder.

SALA: Well, they’re more realistic about it. I’m talking about fine art school now. I did try taking graphic design classes when I was an undergraduate, and that was a whole other thing I wasn’t interested in. It was dead to me, just sterile. “Come up with a concept for a skating rink.” I'd be sitting there going, “What?”

I was still in that childlike mode of just wanting to draw pictures of the things I liked. I couldn’t believe the freedom I suddenly had, that I could draw pictures of whatever I wanted. I would bring them to classes, and people would talk about them.

And teachers will single you out and say, “You’re really good at what you do, you’re great, you won’t have any problem getting gallery shows, I’ll help you out, I’ll give you the name of my gallery director, I’ll give you a recommendation for getting teaching jobs.” But then the teachers mostly lose interest in you once you graduate. They’ve got a whole new crop.

The fine art scene, just like any other cultural thing, is susceptible to shifts in taste. When I was in art school as an undergraduate, painting had been declared dead by somebody somewhere in New York. Conceptualism was in. Colleagues of mine would paint for a while, and then they’d build teepees, or build structures out of twigs, or do performance art. By the time I was almost finished with graduate school, there was a big renaissance in painting in the ’80s. Even the people who were doing piles of leaves as their thesis were starting to do representational painting. And I only ever wanted to do representational painting. So I thought, “Well, I’ve got a chance of getting into the galleries.” But I needed money when I got out of school. So as soon as I got a day job, I thought, “OK, I’ll work, because I need to make money, and I’ll decide what I’m going to do.” And I ended up getting involved in this job, and creating art took a back seat to my new job.

THE LIBRARY

SULLIVAN: When did you get out of art school?

SALA: ’82.

SULLIVAN: And you worked at a university, as a librarian?

SALA: Well, I was a library assistant, even though I did everything a librarian does. Everything except catalog the books, which I technically wasn’t allowed to do. The reason I couldn’t be called a librarian is because I didn’t have a degree in library science.

SULLIVAN: You can’t catalog books without a degree in library science?

SALA: That’s one of the reasons why I faced a dilemma. I mean, I’ve worked in libraries throughout my entire adult life. So I’ve got a lot of experience in the nuts and bolts operations of libraries.

So after art school, I got a job as this library assistant at a small private college. The school’s real claim to infamy is that it had a parapsychology department. So we would get all these people who were interested in poltergeists, shamanism and UFOs. They had ghostbusters teaching there, guys who would go on the Today Show or Nightline talking about ghosts. We would get these guys trying to bend spoons and stuff like that. There were these incredible collections of old books on hypnotism, vampires, and the occult. So it was fascinating to work there. It’s a very small library — and I’d be the main guy there at night and on the weekends. When they hired a reference librarian and his job was basically doing the same thing that I had been doing all along — helping people with research, etc. — that’s when I found myself at a crossroads. He was younger than me, but because he’d spent two years getting a library degree, he automatically made more money and had more authority, despite the fact that I had more experience. So I asked myself, should I go to library school and have a cozy career? Or should I pursue the dream of living as an artist?

At the same time, I was doing occasional illustrations. It was mostly the New Times and other weeklies who kept calling me, even though I had never promoted myself. At the time, it was just a way to make some extra money. I still wanted to be a fine artist, so I would make these goals for myself, to do enough watercolor paintings to fill a new slide sheet. There’s 20 spaces on a slide sheet, so I’d do 20 watercolor paintings over a period of six months, until I’d fill a new slide sheet, then I’d send that slide sheet around. If one gallery rejected me, I’d just put the slide sheet away: “Well, I failed again.”

I was concentrating on survival. I loved reading, so I would sort of sedate

myself in the world of books plus go to movies, hang out with friends. But there was a creative side that wanted to come out.

POP CULTURE

SULLIVAN: Were you following comics during this period?

SALA: When I got out of art school, I had totally forgotten about comics. But I would always go into comic stores, because I never stopped loving Dick Tracy. Chester Gould is my primary influence, from the time I was little all the way through now. At my graduate thesis show at Mills, the secretary who worked in the art department came up to me and said, “Oh now I get it. Dick Tracy, right?” She was old enough to remember the heyday of the strip. I started clipping Dick Tracy out of the newspaper in 1964. Thank goodness I clipped those out, because a lot of those have never been reprinted.

Some of my earliest memories are trying to figure out these Dick Tracy things, these very interesting scenarios drawn in this style that I found fascinating. It was a Chicago strip, so every week it was on the front of the Sunday paper. There were all these scenes of violence and all these really grotesque, ugly villains. Even secondary characters were grotesque. I think a lot of people who grew up in Chicago probably feel the same way. There’s an artist in Chicago named Jim Nutt who’s obviously been influenced by Chester Gould. Then you have someone like Lynda Barry whose obviously very influenced by Jim Nutt. I always loved comic strips, but I lost interest in comic books sometimes in the ’70s. I think it was about the time Neal Adams and his ilk showed up.

SULLIVAN: That’s funny, because on the painting side, you were more representational than what was current, and yet Adams represented the advent of the super-representational into comics.

SALA: When I say representational, it just means I wanted to draw the figure. Jack Kirby was drawing the figure perfectly fine for me, and so was Chester Gould. I’m always more attracted to something idiosyncratic and stylized. Gould was much closer to the kind of figure drawing I liked in art school, the German expressionists like Grosz, Kubin, and Dix. It wasn’t just the way Neal Adams drew the figure that I objected to. I objected to the emotionalism and posturing. And I objected to the way he broke up the comic pages, all that stuff about breaking the borders of the comics —

SULLIVAN: The angles —

SALA: The exaggerated foreshortening, the fakey naturalism. I just hated it so much. He just seemed the antithesis of someone like Roy Crane who was an honest craftsman. Adams, no offense to him personally, was more of a show-off. I think everybody loves most what they loved as a kid. That’s where our tastes are formed. By the time Adams and his imitators were dominating comics, it was probably the mid-’70s. I was in high school, I got interested in girls and lost interest in comics. Probably the last comic I bought before I stopped buying them altogether was Jack Kirby’s Demon, which I loved.

SULLIVAN: Those were great.

SALA: It was a throwback to the early Atlas and the pre-hero Marvels and the early Fantastic Fours. I just loved that rubbery, everything-looks-like-a-toy quality. At that point, Kirby looked as idiosyncratic as Chester Gould.

I stopped reading comics around the time they canceled Mister Miracle. I’d done some work that was sort of comic-oriented when I was at Arizona State. There were some other students who were sort of into comics, but it was all really non-linear, early Heavy Metal, underground comic-type stuff.

By the early ’80s when I was out of art school, I started seeing stuff like Raw, and I became interested in doing comics again. It was around the time I turned 30. I had kind of settled down with the girlfriend who would become my wife. I read that book All in Color for a Dime. I think I was going through a second childhood. I was remembering how I used to love popular culture, and I suddenly remembered that my mom had all this stuff in storage. I started having her send things piecemeal. I didn’t want all of it, because I was still living a kind of spartan existence, and I didn’t want to be overwhelmed with junk. So I asked her, “Could you send me just one box of my Famous Monsters?”

The other thing was, I started reading a lot of old mysteries and hard-boiled detective fiction, tracking down old, out-of-print copies. Some books that had a huge impact on me at that time were any books by David Goodis, Kenneth Fearing, Jonathan Latimer, and Fredric Brown — all incredible stylists. Also The Red Right Hand by Joel Townsley Rogers and The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterson, which isn’t hard-boiled in any sense, but it just blew me away. Of course, I’ve always loved movies, especially old movies — Hitchcock, Fritz Lang — but I really got obsessed with film noir in the early ’80s. The Pacific Film Archive is just down the street from where I live right now. It was always showing great old movies, and so was the UC Theater, which is in downtown Berkeley. Gigantic screen. I remember in the early ’80s at PFA they were showing Sam Fuller and Joseph H. Lewis retrospectives and lots of film noir. The writer and film expert William K. Everson would come and lecture and show forgotten thrillers from the ’30s and ’40s. I finally got to see Judex which had intrigued me since I saw photos from it when I was little, plus the five-part French serial Fantomas by Feuillade.

Before video was so widespread, the only place to see old mystery and horror movies was in repertory theaters or at four in the morning on TV. I think that’s how a lot of film noir and old horror movies should be seen. I’d set my alarm for three in the morning, get up, and watch Stranger on the Third Floor, Somewhere in the Night, Fallen Angel, or Phantom Lady. And then I would go back to sleep, and when I got up it was almost like it was a dream. That’s the way I saw movies I liked since I was a kid, staying up past my bedtime to watch Atom-Age Vampire or Weird Woman or I Walked with a Zombie.

Anyway, I was really getting sort of immersed in “low” as opposed to “high” culture again, and I was reading the early Raws. They appealed to me, because I still thought of myself as a fine artist, and attitude behind Raw seemed to be, “Yeah, we like comics, but we’re better than that. We’re looking at comics in this ironic way.” At the time, that’s what I was ready for. I’ve since turned around on that — now I’m proud to be a part of the whole tradition of hack cartoonists and illustrators. I’m serious. But at the time, I’d just been to art school, and I did think that way myself. For almost an entire decade, I was immersed in academic criticism. So suddenly I was like a kid in a candy store, discovering all this stuff again. “Oh, this is OK, but I can only like it from a distance. I can only like it ironically.”

[laughs] I’m going on too long. I can see these pages, it’s like: “Darcy: Zzzzzz—”

SULLIVAN: That’s the best kind of interview, Richard.

SALA: Jesus!

NIGHT DRIVE, HE SAID

SULLIVAN: When did you do the stories that appeared in Night Dream?

SALA: Night Drive.

SULLIVAN: Night Drive.

SALA: You’re not the first person to make that mistake. The guy at Bud Plant who rejected carrying it said, “Four dollars is a little expensive for Night Dreams, don’t you think?”

SULLIVAN: When did you do those stories?

SALA: I did those stories when I was 29 years old, believe it or not. Right now to me it looks like juvenalia. I was a really late starter. Night Drive was the start of a certain period and The Chuckling Whatsit is the start of a new period. I look at my work from that first period and all I see is the struggle. If people like the work I’ve done, I’m glad. But I think the best is yet to come. You know, Chester Gould was in his prime in his 40s. That’s when he created Flattop and some of his best characters.

But as far as Night Drive, I wasn’t sure if I was doing art or popular culture. I think I thought I was making art. There is a clue in there as to the direction I would eventually go. At the very end, there’s a story that I almost left out, called “Invisible Hands,” which was my take-off on my love of pulps. It was non-linear, it was broken up, and I didn’t really bother to end it. I thought it didn’t need an ending. It was supposed to be a chapter from a non-existent serial — it’s like Andre Breton and the surrealists. They loved stuff liked Fantamos. Andre Breton did this famous thing where he’d walk into the middle of a movie and watch a part of it, and get up and go into another theater and watch part of another movie, and would never see the entire movie.

So I did this thing, “Invisible Hands,” which was not meant to be taken seriously. The rest of Night Drive has more to do with the world of fine art than the world of comics.

I had never stopped writing. I would take the BART train to work every day, writing, then at home, I’d draw pictures to go with the stories. The main influence on me was not so much Raw or Weirdo, but Mark Beyer’s Dead Stories; when I saw that, it was a revelation. I really related to his feeling of negativity and his primitive art style. I looked through it to see who the publisher was. I couldn’t find the name of a publisher, and it dawned on me that this guy did this himself. I followed Mark Beyer’s format with the card stock cover, magazine-size, for Night Drive.

If I haven’t said it before, I should say that I never thought I would make it to 30. One of the reasons I couldn’t really imagine becoming a successful artist in my 20s was that I had been thinking about suicide every day since the time I was a teenager.

SULLIVAN: Seriously thinking about it, or romantically?

SALA: There were times when I felt really bleak, and I just felt negative all the time. I couldn’t see a future. When I was living in Arizona, that was another thing — I didn’t relate to any older people.

SULLIVAN: Lots of older people there!

SALA: White shoes and white belts, and they’re wearing bolo ties. You’d look at these guys, with their beer bellies hanging over their tight jeans, and you’d think —“That’s me when I get old?” I couldn’t picture it I thought, “I’m not on the same planet as these people.” I didn’t get how to go from being this kid that I was then to being that person.

But when I came to the Bay Area, I started seeing old people who looked like I imagined I would like when I was old. Guys that were like me, but they were old. My God, that’s what I would look like old! I can’t tell you what a revelation that was. Because until then I thought a guy like me wasn’t meant to live beyond a certain age, because I didn’t see anybody who looked like me and was old. I was a little crazy.

So when I read Dead Stories, it really hit a chord, that whole feeling of helplessness, hopelessness. It was almost a validation that a person with my attitude, my feelings, could do something like that. Of course, it was the time of punk, everything was sort of do-it-yourself, and I thought, “I’m going to do it myself. I’ll do my own book.”

Like I said, I had no knowledge at all of how the market worked. I knew about Bud Plant, because I’d seen his name around. I remember ordering Crumb undergrounds and Rick Griffin undergrounds from him when I was in high school. The only other thing that I knew was I saw Raw being sold at City Lights. So I went into City Lights with Night Drive, and they took some copies. So there was a time when the only comics being sold at City Lights in San Francisco were about 10 copies of Night Drive and a bunch of copies of Raw, I was really proud of that.

To this day, people from around the world will tell me that they first got a copy of my book at City Lights. I also was carried in Printed Matter in New York, and also to this day, people tell me that they found copies of Night Drive in New York during the mid-’80s. There were also some copies in Portland and Seattle, but I’ve never heard any people tell me about buying them [laughs] so who knows what happened to all those copies?

SULLIVAN: Did it lead to more work?

SALA: One of the reasons I did Night Drive was to try to get other people to give me illustration work. I sent it to some places in New York that I thought were hip places, that paid no money, of course. There was an alternative weekly out here that I had seen some of Charles Burns’ stuff in called Another Room. I sent them some stuff and they ran something.

I had sent a copy of Night Drive to Raw, too, and I heard back from somebody at Raw, I think it was Francoise Mouly, saying that they liked Night Drive, and would like to see more stuff. So, suddenly, I was motivated — ’cause I loved Raw. I did a couple of strips for them and sent them off.

Then, there was a really long period where I was just waiting. At one point, Mark Newgarden sent me a copy of this magazine called Bad News, which was sort of an off-shoot of Raw. He was working on Raw at the time as Spiegelman’s assistant, and he told me, “You’re not going to be in Raw but you’re going to be in Bad News, which we’re doing in a format like Raw.” He sent me a sample copy, and it looked great. I remember there was a Kaz cover. So I did a three-page thing for Bad News and sent it in, and then waited for another long period of time and never heard anything. Occasionally I would call or write Mark Newgarden, and he’d say, “Oh, don’t worry about it, everything’s fine.” But I was fatalistic, and thought, “It’s never going to happen.”

Then, one day I got a letter from Newgarden saying, “The bad news is that Bad News is canceled. The good news is, now you’re going to be in Raw!” I was like — “Oh my God!”

That’s when I heard from Art Spiegelman. He told me that I’d have to condense a three-page story into a one-page story. Then I could be in the next issue of Raw, which as it turned out was the last large-size issue.

SULLIVAN: Did he give you any other direction besides turn it from three pages into one page?

SALA: Yeah. Actually, they mocked up a copy showing me how it could be done! I saw him and Francoise as true editors. They were trying to edit their magazine, their vision, so I went along with it. What I didn’t know was that that issue of Raw would take like another year or more to come out. I was waiting for it to come out, and so many times I gave up, like it was never going to come out. I stopped telling people I was going to be in Raw, because it would just seem like a pipe dream. I thought, “As soon as Raw comes out, I’ve made it.” Of course when it finally did come out, no one noticed me anyway.

By then, I was aware of Fantagraphics, and I was interested in what they were doing. So I sent Gary Groth a copy of Night Drive, and told him I wanted to do a book. I think he wrote me back, saying he wasn’t sure about a book, but that they were going to start their own anthology, which was going to be a West Coast version of Raw. I got excited about that, because it seemed like they might be able to pull it off.

SULLIVAN: Was this Prime Cuts?

SALA: It ended up being Prime Cuts. I think even Gary now would tell you it was nowhere near a West Coast version of Raw. But I got really excited, and I sent them a bunch of stories. I was really hyped to do it.

I think I was in the first issue, maybe the second issue, but then he ended up sitting on some of my stories for a long time, and sometimes even forgetting that he had them. I would have to write him and remind him, “Gary, I sent you this other story.”

KING OF ANTHOLOGIES

SULLIVAN: Tell me about you got into Blab!

SALA: Monte Beauchamp was one of the first people who bought Night Drive when I was advertising it in the Comics Journal. Bhob Stewart saw the ad and wrote to me, saying, “Look, I do reviews for Heavy Metal. If you send me a copy, I might review it.” At the time, I was so broke, I was like — “This guy wants a free copy, goddamn it!” But I did it. And he was true to his word! There was a little blurb about Night Drive in Heavy Metal, with my address, and it was amazing what that did. I got orders from Scotland, New Zealand, and other, you know, far off lands. I didn’t realize how wide a circulation Heavy Metal had. I really was grateful to Bhob Stewart for that.

Monte ordered a copy from the Journal ad, too. He’d seen my work in Prime Cuts, and so by about the third issue of Blab! he wrote me saying, “I like your work, and I want you to be in the third issue.”

I’ve been in Blab! every issue from the third issue on. He’s a good person to work with. He pretty much lets me do whatever I want to do. He used to throw a theme out at me, like, “What do you think about doing a story about alcohol in this issue?” I’d work his theme into whatever story I want to do, and that seemed to work out just fine.

SULLIVAN: You did a story with Tom DeHaven for one of the anthologies —

SALA: For the last issue of Raw. Yeah, it was interesting. I respect Tom DeHaven a lot. I had read Funny Papers, and it’s a really, really good book.

That was an interesting experience. Spiegelman felt that cartoonists should try to broaden their horizons by collaborating with “real” writers. I was game, because it was Raw.

Luckily, Tom DeHaven liked my work and was sympathetic to what I was doing. Bless him, I think, he tried to write a Richard Sala story, which I appreciated. But when I got the script, it was like a movie script. It was huge. There was no way we could do it. But he was nice enough to realize we couldn’t do it as written, and we played around with it. Most of it’s his, but I added a few of my own touches.

I’m not interested in collaborating anymore. I have my own stories to tell. I think that an artist’s singular vision is important. The whole reason I got into doing comics is because I liked to draw and write.

SULLIVAN: You were in Drawn and Quarterly for a few issues, and then not in it. How did you get in, and why did you get out?

SALA: Chris Oliveros sent me a copy of the first issue and asked me to contribute. There was some good stuff and some bad stuff, as in most anthologies. But what attracted me to it was that he was going to do color. I did something for the second or third issue, and then he would call me and ask me to do some other things, and as long as it was color, I was really interested.

But it was bad timing, because the color in those early issues is atrocious. I was doing these colorful watercolors, and they came out all muddy and horrible. The reproduction was blurry, it was off-register, printed on some terrible paper. So I tried to simplify the line work and lettering but nothing helped. Chris kept saying they’d fix the color on the next issue but it never seemed to happen. They looked awful, and every time I was more and more discouraged. And at the time I didn’t want to do these little one- or two-pagers any more, but that’s all he wanted me to do. I think he could tell my heart wasn’t in it.

Actually what happened was kind of funny, because the last one I did was a black-and-white, three-page piece. It was my all-time favorite of all the ones I did for him.

SULLIVAN: Which one was it?

SALA: It was called “Time Bomb,” and it was very personal. Once again, I was writing sort of enigmatic prose poetry. Of course, no one else liked it. No one could make heads or tails out of it.

SULLIVAN: That was one of your best ones!

SALA: Well, no one else seemed to like it. When Chris wanted to pick a piece for The Best of, I said either that one or “One of the Wonders of the World,” which is my only other one of those that I liked. And he went for one of the really easy early ones.

SULLIVAN: “Credo”?

SALA: That was it, yeah. That’s fine, but I’ve got notebooks filled with stuff like that.

I think that was the nail in the coffin. There’s no bad blood, as far as I know. But this happens a lot as an illustrator: You work for various clients, and then they become tired of you, or they think, “Okay, I’ve seen it, that’s enough.” Thank God Monte has stuck with me and wanted to use me in every issue, and let me experiment, A lot of times, an artist’s work can really flourish if they’re lucky enough to find an editor who’s sympatico with them. Of all the anthologies I’ve been in, my experience with Blab! has probably been the best, because Monte has let me experiment. And I’ve been in a lot of anthologies.

SULLIVAN: You did seem ubiquitous for awhile there.

SALA: I was in just about every fucking anthology that ever existed. Some I’m proud to have been a part of, like J.D. King’s Twist and Mark Landman’s Buzz, but I’ve also been in some really, really bad ones. My girlfriend, now my wife, was in school, studying to get her Ph.D. in psychology, which now she has. I was trying to support us by working at the library and getting illustration work.

When these anthologies started coming along, it was almost like an exorcism, like I was doing these stories to get something out of my system. I look back at them now — most of them are collected in Hypnotic Tales — and they all follow a certain rhythm, a certain pattern, like a recurring dream.

But at the time, when I was writing for these anthologies, I wasn’t going back and reading the other ones, I would just write a new one and send it out.

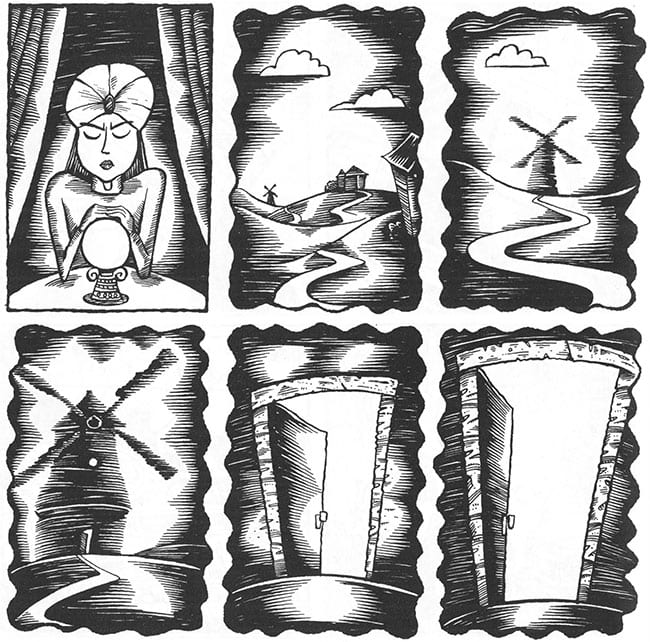

My idols were people like Kafka and Borges, who were masters of enigmatic short stories, my favorite form. I was reading Grimm’s fairy tales every night before going to bed and I’d wake up with a new, bizarre premise. Another guy I love is Donald Barthelme, who has a quote, “Fragments are the only form I trust.” There’s this great Borges quote that I ran in Night Drive — “The solution to the mystery is always inferior to the mystery itself.” Looking back now, I think that my obsession with unexplainable enigmas was a reflection of where I was at the time — at some kind of unconscious crossroads, not knowing which path to take.

DREAMS AND MIGRAINES

SULLIVAN: While you’re mentioning writers, some of your comics reminded me of a writer named Barry Yourgrau, and I wanted to know if you were familiar with him.

SALA: I am. When I discovered him, I was like, “Wow — this guy’s on my wave-length.” I have a couple of his books —

SULLIVAN: Wearing Dad’s Head and —

SALA: A Man Jumps Out of an Airplane, yeah. I think I can tell who his influences are, they’re my influences, too. They’re Russian writers, Daniil Kharms, Aleksei Remizov, Gogol, etc., Kafka, again, Absurdists. I’ve always had a healthy — or an unhealthy — love for the absurd. When people say that Yourgrau’s stories are dreamlike, or when people say that Kafka’s stories are dreamlike, they’re missing the entire point. They’re little slices of the absurdity of life. I think it’s selling them short to say they’re like dreams. It says there’s no art to them.

SULLIVAN: In your Super Anthology Man period, there seemed to be a phase where your stories were less to do with the pulp, Edgar Wallace archetypes, and more to do with your dad menacing you or your friends betraying you, where the situation would get more and more surreal. Those are the ones I related to best. On the face of it, events are completely absurd, at another level, you’re thinking, oh my god, I know exactly how this feels.

SALA: There’s a feeling of being alienated.

I was going through my notebooks recently, and I noticed that I once considered doing a book of illustrated Kafka stories, but I decided that because his stories are so strongly psychological, they just shouldn’t be illustrated.

SULLIVAN: Well, the feeling that underlies writers like Kafka, and that underlies your work, I would say, is guilt. For example, in some of your stories, the character has forgotten that he is supposed to do something important, like go to a party, or that he’s meeting somebody. In the most extreme cases, the character has forgotten that he’s in fact killed a few people [laughter]. He shows up at the beginning of the story as a person who thinks he has forgotten where his watch is, or something, but in fact turns out to have forgotten something much deeper. Your lead persona is often a blank, blond, happy-faced guy, who suddenly realizes he’s in this terrible world, and is he part of it?

SALA: And you’re asking where does that come from?

SULLIVAN: I don’t know. Maybe you’ve already told us. [laughs]

SALA: I think this goes back to what I was saying before about being at some crossroads, about being stuck. In Arizona, I used to get terrible migraine headaches. When I moved to California, the migraines went away. During the time I was working at the library, and doing illustration work and anthology pieces for comics, I was feeling pretty stressed out. While I was at work one day, I was sneakily working on some sketches for an illustration, sketches I had to send the following morning. I was trying to do all these things at once, and I felt all this pressure. I wasn’t getting enough sleep or enough to eat, and I was busy trying to do too many things. Suddenly I got a migraine headache, right there at work. I had just arrived for my night shift, but it was so bad that I had to leave. I don’t know if you’ve ever had a migraine …

SULLIVAN: No, thank God.

SALA: They’re so debilitating that you can’t even talk or see. So I rushed home, and I was panicking: Am I going blind? Am I going insane? Why am I getting this again? I’m trying to do too much. I’m burning the candle at both ends. My diet’s fucked, you know, and I’m full of anxiety.

After that day, I’d start going in to work, and I’d remember the migraine attack, and I’d start being afraid that I was going to have one again. It affected my performance at work, and it made me think, “What am I doing? I want to be an illustrator, and I work in this library.” I was stuck.

I started thinking about my life. I’ve always been interested in subtext, something behind the surface. I suddenly realized that the whole library system, which I’d worked in since I began in college, is a maternal system. All my bosses were women. It was very comforting and very cozy, these rooms that were carpeted and soft and quiet. I suddenly realized — this is maternal, this is the womb, this is the mother. The other thing, the thing about being an artist, about drawing, my urge to create, is the paternal side. My father was the frustrated cartoonist. That’s the person I’m having a struggle with. I had so many problems with my father, that at some point, I swore that I would never be like him.

Now, the creative side of me was being held in because some part of my unconscious thought I was becoming more like my father. If I chose illustration, I’d be a small businessman, self-employed like my father.

Suddenly I was at this crossroads. Am I going to join the ranks of my father, or am I going to be in the protective womb of the library, surrounded by people who are smart and polite, surrounded by books. By the way, these are academic libraries, not public libraries. [laughs] Big difference.

SULLIVAN: But even in a public library, the whole point is order. It’s the ultimate controlled environment, where everything is in its place.

SALA: That’s why I’m making the point, because public libraries are a lot more chaotic. Although, believe me, we did get our share of crazy people. All libraries do.

Anyway, I found myself facing this dilemma. I was aware of this split right down myself. I’ve always been fascinated by concept of the double. I don’t believe in astrology but I’m a Gemini, and as a young kid, someone said to me, “Oh, that means there’s two sides of you.” Somehow this got wedged in my subconscious. Now there was this maternal side fighting with this paternal side, and I didn’t know what to do. I’ve always felt a struggle with duality, between two sides of myself. For example, how do I reconcile the side that loves fine art and literature with the side that loves lurid pulp fiction and comic books?

I saw a psychologist, who really helped me. A lot of the things I can talk about easily now, I couldn’t talk about then: My family and my father and everything. I came to understand, for example, that my love of monsters and scary movies may have helped me significantly in dealing with my childhood anxieties. Horror movies have never scared me. I’d go to them purely for enjoyment. They’re somehow reassuring to me.

So I made the decision to quit the library, and even then it was hard for me. My boss was so nice, she let me go on a leave of absence for six months, to see if I could make it as an illustrator. I was already earning more money as an illustrator than I ever made at the library. I was like, “Wait a minute! I’ve only been an illustrator in my spare time.” [laughs] “How is that possible?” Once I took my leave of absence, I never went back.

There was some unconscious turmoil going on, and somehow my stories were exorcisms for me. Certainly I want people to bring their own experience to the stories and enjoy them, the way I relate to Kafka, for example. At the same time, they’re little psychic snapshots of my psychological state at that moment. People are welcome to look at them and see deeper meaning, or they’re welcome to say, “Oh! Another story based on a dream,” which of course they aren’t.

PERSONAL VOCABULARY

SULLIVAN: How did you hook up with MTV and Liquid Television?

SALA: I got a call from Colossal Pictures in San Francisco, who were planning a cartoon show for MTV. They liked this one story I had done in Night Drive, “Invisible Hands” — the one I didn’t think anybody else would like or relate to because it was based on love of ’30s genre-stuff and I couldn’t believe that that’s what MTV would want. I said, “Are you sure? That’s the one you want?” And they said, “Yeah, but we want you to finish it, and turn it into a real story.” I even wrote them some other treatments, saying, “If you want a cutting-edge thing on MTV, why don’t you try something like this?” They’re like, “No, no, we like this one.”

That was great because that was what I really wanted to do — write these cool mysteries with horrific overtones. That started me going in that direction.

SULLIVAN: Some of your stories seemed almost component-based. You have a range of components: a secret cabal, a severed hand in a box, etc. Some stories seem to be constructed entirely of these archetypes. And I wondered whether you — being an introspective person, unlike many cartoonists [Sala laughs] — struggled at this. Whether you thought, “I’ve really got to go in a different direction, but I’m tempted to pursue my obsession and do another story about the secret cabal.”

SALA: Well, I’m a great believer in a personal vocabulary. These were motifs that I was using as personal symbolism for my own life. At that time, I couldn’t have done a story about an unwed mother working in a sweatshop in New Delhi. I was exploring a personal vocabulary that I felt very comfortable with, and exploring it over and over again, to the point of obsession or compulsion. I certainly feel like I do fall back on things that I love. As you can imagine, I have notebooks filled with lists of things like wax museums, and I’d have to check them off. It would be like — now, you’ve already used that one, Richard. You used the taxidermy shop, and you used the wax museum —

SULLIVAN: The clock shop —

SALA: Well, the clock shop was a personal experience, because my dad had the clock shop. Yeah, a lot of it was stuff that I obsessed about as a kid, these mysterious little neighborhoods, mysterious little shops. You have to wonder: “Am I repeating myself, am I spinning my wheels, or is it just what I do? Is this just who I am?”

Many artists actually have a specific vocabulary of obsession. Look at Hitchcock: he told very similar stories over and over again, and those are the ones that people love. When he tried to do something different, a screwball comedy or a period piece, people just didn’t accept it. As an artist, your goal should be to recognize your own personal obsessions, your own personal vocabulary, and use it. There was a review of my work where a guy said, “Enough with the mysterious killers and secret societies.” That’s like saying, “I’d sure like Peanuts a lot better if it didn’t have those kids in it.” I mean, it’s what I do. If you don’t like it, read something else.

SULLIVAN: I’ve often had the sense that you were trying to get to the ultimate example of your work. “When I arrange these pieces in exactly the right order, I will never have to do this again. Because it will be perfect.” Which I guess is the obsessive-compulsive thing.

SALA: Sure.

SULLIVAN: But as you say, you’re also doing it for the audience, trying to get them to get something. What do you want them to get? What do you think they’re not getting when they read the story the first time?

SALA: Maybe it’s not so much that they’re not getting something, as I’m not being heard. You can see the motif in a story like “Hidden Face,” where no one recognizes the guy. I suppose there’s a certain amount of insecurity and paranoia that no one notices you. On the other hand, look at episodic television, where the same motifs, characters and plots are recycled endlessly. Just consider my stuff part of that same cauldron of popular culture.

SULLIVAN: Here are some elements of your vocabulary — is there a meaning inherent in the symbol itself that makes you say, “It’s okay for me to keep bringing that one back”? We just talked about losing face and losing identity. Dismemberment?

SALA: Dismemberment, at its base, psychological level, is certainly a castration symbol, and it’s over-used. I remember watching the first season of Liquid Television, where every fucking cartoon had cute bunnies chopping the heads off other cute bunnies, or people chopping things up. And then on came my cartoon with a cut-off hand. I was like, “Jesus fucking Christ! Is every white male in the country obsessed with castration?”

I don’t want to get too Freudian about any of this stuff. Let me say this, as a caveat to all these questions: When I was in art school, people were always appropriating symbols from other cultures, primitive art, folkpainting. They thought that somehow that would give their painting meaning, the same meaning it gave to some primitive culture, which is absurd. We have our own symbols in this culture. A telephone to me is just as powerful a symbol for my culture as something like a spiral was to some primitive culture. What’s wrong with just painting a telephone, or a guy talking on the telephone? That to me is just as symbolic as a painting of an open hand, which might have lots of meaning in, say, some aboriginal culture, but doesn’t have any meaning per se in this culture.

So I started thinking about dealing with my own personal vocabulary, working up my own symbols, various kinds of things that would be my touchstones, my visual language: curio shops, hypnotism, plastic surgery, crystal balls, lots of things appropriated from that great well of ’30s culture.

SULLIVAN: So the question is, why are these your symbols? Why, to take another example, puppets?

SALA: I guess because they are somehow — they’re — I don’t know why. [laughs] Possibly they hold some twinge of nostalgia, whether I’d seen it in some old movie, or it’s something that might have seemed mysterious to me as a child. With puppets, once again it’s something behind the surface. Who’s working the puppet? The puppet may be smiling, but what’s the face of the puppeteer look like? You could actually talk for hours about all of the metaphorical meanings of a puppet. To me, a puppet is filled with symbolism. As a matter of fact, I have a puppet in my new story [laughs] that I’m working on right now for Evil Eye. But once again, that’s who I am, that’s what I do, you know. Next.

SULLIVAN: The duality you’re talking about is going to run through a lot of the hypnosis and the secret cabals, but here’s an interesting one: Weddings.

SALA: Hmm, weddings.

SULLIVAN: Even though you don’t overtly deal with sex much in your material, you have a lot of people getting married.

SALA: I like to take things that are happy in our culture — birthdays or weddings — turn them inside out, and have fan with what’s behind the surface.

It’s that whole “David Lynch quality.” When Blue Velvet came out, everybody was tripping over themselves to say “Oh, he’s seeing something that’s behind the surface of something that’s really sweet.” Our culture — especially critics — has such trouble with anybody who can see the enigmatic in everyday life. For a long time anything that was enigmatic or strange, their word was Kafkaesque. Then for awhile it was Lynchian, then it was Tim Burtonesque. Well, in Europe, you’ve got Bunuel, you’ve got Cocteau, Polanski, Bergman — this stuff has always been there. It’s as if in America, it’s amazing when people see behind the surface. “Oh, there’s something more going on!”

Yeah, there is something more going on. There’s always been a lot going on. That’s what I’m interested in, what’s behind the surface. So when I do “Honeymoon,” there’s a guy who finds out his marriage is not what he thought it was going to be. “Proxy” was Tom DeHaven’s idea. But in “Birthday Party,” where the guy’s birthday goes wrong from the first moment, that’s almost me making fun of myself and my feeling of guilt, as if I can’t allow myself any kind of joy without things instantly going bad. Even at my most neurotic, I attempted to write stories like that, that poked fun at my feelings of guilt and paranoia, much as I think Kafka also chuckled at his own neurosis.

SULLIVAN: Everyone in your stories seems paranoid.

SALA: Paranoia does play a role. I’ve always been a bit paranoid, though certainly not in the clinical sense. But the feelings of paranoia I do have are apparent to people, I think. My art teacher Jay DeFeo, during one of the first conversations we had, said, “You’re a bit of a paranoid, aren’t you?” And I said, “Why? Am I? Do I look that way?” [laughs] And she said, “That’s okay, I’m paranoid myself. It’s good to be paranoid, because paranoia sharpens the senses.” I’ve always remembered that.

I went to Disneyland as a kid. Here I was, almost an adolescent, looking at these figures of Goofy and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs wandering around, and all I could think about is, “What does their face really look like behind that? What do they really — they’re not smiling like that. They might be frowning.” But there’s this facade — the big happy heads.

SULLIVAN: Does it bother you that people would pick up on the personal vocabulary and just see it as repetitious?

SALA: I guess it should bother me. I don’t want to be someone who — well, I don’t know. Should it bother me? [laughs]

SULLIVAN: It should bother you, but does it? Do you think, “I’d better switch gears here, because if I do another story about people meeting in the cellar with hoods over their head, people are going to accuse me — ”

SALA: But see, I do those stories for myself. Like a lot of cartoonists, I’m not really doing comics for money. I’m doing them for myself, and if people don’t want to read my work, they don’t have to. I love the conventions of the thriller genre. We were talking before about Doc Savage — did you read a lot of Doc Savage books as a kid?

SULLIVAN: Yes, I’m embarrassed to say.

SALA: Well, wasn’t there something comforting about them? If there were some elements that were left out — say, Ham and Monk didn’t argue in a certain book —didn’t you feel there was something missing? There’s something comforting when the same elements get mentioned.

SULLIVAN: It was comforting until I read that book by Philip Jose Farmer —

SALA: Doc Savage: An Apocalyptic Life.

SULLIVAN: —where he explained that … I can’t remember the guy’s name who wrote all the books.

SALA: Lester Dent.

SULLIVAN: Yeah. He used a formula. And he actually had the formula written down.

SALA: But I loved that!

SULLIVAN: It was disturbing to me, because I want to think that stories are organic manifestations of something that might have happened, instead of just, “Doc has to be in disguise in Chapter One. In Chapter Three he reveals himself” — oh, man!

SALA: But see, I love that. I admire any writer who’s got a formula that they can make work. We’re talking about popular culture and genre fiction here, right? Not high art. I love the writer Walter Gibson, who created The Shadow. He could never have written as many Shadow stories as he did if he didn’t have a formula. Look at the early James Bond movies, which all follow a very similar, comfortable pattern. There have been tons of parodies of Bond movies, but the originals have out-lived all of them, because the originals didn’t take themselves seriously, they embraced the formula. I mean the formula, ideally, is in the plotting, not the writing, so the reader is pretty much unaware of it. It’s simply a springboard for inspiration and for getting the job done.

Another writer that I’m fascinated with is Harry Stephen Keeler, whom I’m sure many people would consider a classic bad writer. He wrote lots of really “bad” detective novels that involved absurd coincidences, absolutely unbelievable names and events, ridiculous dialects, and mind-numbing digressions. He’s forgotten now and completely out-of-print. There’s a little group of us who are into him. Apparently, he’s even got a web site [laughs]. He had a formula, too. He had files and files of clippings and ephemera. Whenever he started writing a story, he poured stuff on the floor, and just picked elements out at random, and that would make up the story, which I think is a brilliant way to write.

So whenever you come up with a formula, I think that’s great. A formula is just a way to harness the creative process. If you have any talent at all, and you’re interested in writing at all, the drive is there. What you just need is the structure.

KIDS

SULLIVAN: There don’t seem to be very many children in your stories.

SALA: Yeah, true. I don’t know why. There was going to be a kid in The Chuckling Whatsit. He was going to be a computer genius. I took him out. He was going to be my very first foul-mouthed character. But then it just seemed so clichéd and old-hat to do a foul-mouthed kid. So he got cut out.

In the first issue of Evil Eye there are some little hungry kids.

SULLIVAN: I liked those guys. I thought, “I’ve never seen this in a Richard Sala story.”

SALA: That’s true. You know what? I’ve drawn kids hundreds of times in illustrations, although it’s not really my forte. One of the very first times I had to do an illustration of kids, the criticism that came back from the art director just floored me — he said the kids looked satanic. It helped me realize that the way I was drawing adults wasn’t working for kids. I was drawing little slanty eyes, and a bit too expressionistic, so that the kids didn’t look like innocent children. They looked like … Nazi gremlins.

For the longest time I tried to draw them as little adults, and it just didn’t work. Wally Wood and Jaime Hernandez — two of the greatest comics artists ever — both always draw kids as cartoons and I learned from them. That works really well.

UNSOLVED MYSTERIES

SULLIVAN: One thing I’ve always wondered about your stories is how you are intending somebody to take them. I don’t know if I should admit this to you, but when I saw “Invisible Hands” and when I read Chuckling Whatsit, they didn’t work for me as mysteries. Everybody seemed culpable, and once you know that everybody in the cast is a murderer, who committed this particular murder loses some of its formal significance.

SALA: [sighs] Well, they’re not whodunits. They’re thrillers.

SULLIVAN: Yeah, but the driving momentum was “Who did this?” And I was wondering, do you intend for somebody who reads The Chuckling Whatsit to read it as a story, and to be involved in the narrative? And if not, what do you think people are going to with the thing?

SALA: Like I said, I do them for myself, and if they don’t communicate on a certain level, I guess that lets a lot of people out. But it sounds like what you don’t like is my love of film noir and German expressionism. In those worlds, everyone is a suspect, everyone is culpable, even the hero. The world is a threatening place, filled with grotesque faces, dark alleys, and the constant possibility of sudden, violent death. Anyone who identifies with a bewildered innocent, caught up in some kind of mess, in a dark, corrupt place, will allow themselves to be drawn into that world. Everyone else can read power fantasies about muscle men wrestling in Spandex, or little alternative cutesey-pie tykes, or whatever else is out there on the racks.

SULLIVAN: But do you mean your work to be ironic or …

SALA: All my work is tongue-in-cheek, to some degree. I remember one of these Gen-X kind of slacker cartoonists talking to me when Thirteen O’Clock came out. He says, “I didn’t get it.” “What do you mean, you didn’t get it?” “I didn’t get it. I read Thirteen O’Clock and I didn’t get it.” It blew my mind, because I realized I wasn’t sure what his expectations were. The story wasn’t meant to be taken seriously, but it wasn’t a laugh-out-loud comedy, either. It certainly wasn’t ironic in any kind of “wink-wink, nudge-nudge” way, but it’s tongue-in-cheek and possibly a bit post-modern in that it’s self-referential. A good analogy might be the old Avengers TV show from the ’60s, which I loved. The ’60s were the golden age of spoofs, camp, and black humor: The Avengers, Dr. Phibes, Barbarella, The Loved One, Dr. Strangelove, etc. Maybe the world has become way too earnest and uptight to understand any of that now.

I guess I want people not to take it simply on the surface level. Look for something more. There might be something in there you’ll find that is universal: the universal feeling of anxiety, helplessness, mistrust, paranoia, jealousy, whatever. I thought Chuckling Whatsit was a very romantic story.

The stories in Hypnotic Tales are me exploring my subconscious. I wrote Chuckling Whatsit as a thriller. But it ended up telling me a lot more about my own unconscious than I had prepared myself for. Symbols can be perceived by any sensitive reader. The final conflict at the end — the shattering of the perception of the “good” mother and father and the revelation of the “bad” mother and father — stuff like that, artists have to allow to come out of their unconscious. A reader doesn’t have to notice all these things to enjoy the strip. All I’m saying is that it makes the story richer if it can be read on more than one level.

THAT DAMN CHARACTERIZATION

SULLIVAN: You talk about subtext and what’s behind things, yet it’s all done at the level of the images and the symbols, because you employ characters who are always two-dimensional. That is, if they’re not one-dimensional. You don’t seem interested in telling stories about people with varied sides to their personalities.

SALA: Well, to be honest, I’m not, you know, all that interested in characterization.

SULLIVAN: You say it like it’s a dirty word, like of course you hate characterization! Who wouldn’t hate characterization?

SALA: What I’m writing are fever dreams. One person thrashing about in a world he doesn’t understand. Don’t bother searching for anything resembling a folly-rounded character. Don’t bother looking for any situation that has anything to do with reality. In other words, characterization is subordinate to plot and atmosphere. I’ll sacrifice characterization in a second for atmosphere. I don’t care what the character had for breakfast.

I mean, these stories are basically extensions of my own personality. People used to ask me, “Why don’t you do autobiographical comics?” And I would say, “I’ve been doing them. These are my autobiographies.” That’s why I did that one comic as a joke, “All About Me” — it couldn’t be less about me.

SULLIVAN: But take Chester Brown. There are a lot of different aspects of characters that come out — subtly. He’s not banging you over the head with it. But the story wouldn’t make sense without that. You have to have been picking up on what was driving him, as opposed to “I do this because I’m the hero and I do this because I’m the mad doctor.”

SALA: Well certainly I’m not in Chester Brown’s realm. We’re going for different things. And if by “mad doctor” you mean Vogardus in The Chuckling Whatsit, both he and Celeste are as developed characters as I’ve ever done, though it’s up to the reader to put the pieces together. The Chuckling Whatsit is really Vogardus’s story. The epigrams at the beginning are about him. The character Broom is kind of like the reporter in Citizen Kane — actually I had Mr. Arkadin in mind — he helps the viewer assemble the pieces.