Though generous to his fans, and generally warm with his peers, Tezuka Osamu (1928-89) was not above letting professional jealousy get the best of him. The first time this trait reared its head in public was in 1953, when, in a series about comics-making and comics aesthetics for Manga Shōnen, the new prince of manga took a swipe at his foremost competitor, Fukui Ei’ichi (1921-54), who was older than him by seven years.

The series in question, Manga Classroom (Manga kyōshitsu), had begun serialization the previous year. It was partially modeled after Manga College (Manga daigaku), the best-selling tutorial Tezuka had created in 1950 for the Osaka publisher Tōkōdō.

After dominating the Osaka akahon market, Tezuka had only recently begun working for Tokyo magazines. The legendary Jungle Emperor (Janguru taitei, 1950-54), published in the same Manga Shōnen, was one of his first such serials. Manga Shōnen was famous not only as the home to this proto-Lion King title, but also as a venue to which young cartoonists could submit short four-panel work for review by Tezuka or the magazine’s editors or other contributing artists. Select submissions received critique within the magazine’s pages. The best received a small pin badge as award. Amongst the youngsters who got sucked into a life of cartooning through this exchange were Ishinomori Shōtarō, Akatsuka Fujio, both halves of Fujiko Fujio, Tatsumi Yoshihiro, and Sakurai Shōichi.

Manga Classroom was designed to support and expand this fan-amateur world’s sphere of influence. It offered simple instruction about such basics as what pen to use, how to structure jokes, how to express emotion, how to express movement, and how to apply color. It also provided jocular commentary on the aesthetics of comics in the four-panel and especially the extended breakdown formats. Sometimes submitted cartoons appeared directly in the series’ pages. This was not necessarily a blessing. Professor Anything and Everything (Nandemokandemo hakase), Tezuka’s avatar and narrator for the series, might praise your work for its good drawing or clear structure. But more likely, your ham-fistedness would be upheld as an example of how not to cartoon.

Kids were in no position to fight back. When Professor Anything and Everything turned his attention to the work of other professionals, however, he courted trouble. Stiff prewar comics and contemporary adult manga (meaning, not porn, but wiry multi-panel comics for men’s humor magazines) receive repeated joshing. So on occasion do Tezuka’s peers within children’s manga. Manga Shōnen was far from a best seller. But given its status amongst discriminating amateur cartoonists, Tezuka knew, as others knew, that whatever he said in Manga Classroom, the kids were sure to pay attention to. It was the perfect place for Tezuka to build allegiances, in other words. It was also the perfect place to make enemies.

Such was the so-called Fukui Ei’ichi Incident. By turns silly and tragic, this famous episode in the history of early postwar manga marks an important juncture in the evolution of Japanese comics form. It also provides crystal example of how manga’s new hero was no angel.

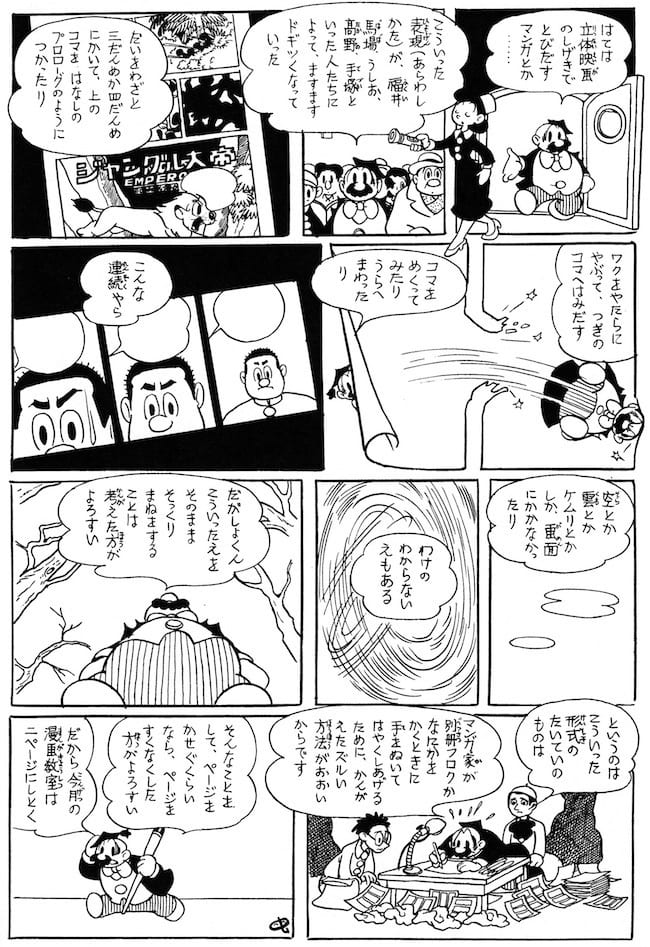

The inflammatory segment of Manga Classroom was titled “New Modes of Expression” (“Atarashii hyōgen”). Published in Manga Shōnen in the autumn of 1953, it opens with the Professor striding across the page, demonstrating what manga used to look like back before the war, how “like on a theatre stage . . . manga characters simply walked entered and exited from one side [of the panel] to the other.” He adds, “Ain’t that boring, kids?”

The Professor then states, in what has become standard explanation of postwar manga’s development, that what guided cartoonists toward new and more dynamic sensibilities was the movies. The main such techniques included: the close-up of faces, stylized details of feet, tilted ground planes, images of pure darkness, and super-planar effects inspired by 3D movies. Amongst “new modes of expression,” the Professor also lists reflexive slapstick jokes about the representational conventions of comics, slow filmstrip-like breakdowns, isolated shorthand drawings of sky and clouds, and “pictures that don’t make any sense,” which are represented by a panel filled with whirling speed-lines.

“But kids,” says the Professor, while depicted in extreme frog’s eye view distortion, “beware of copying these kind of pictures.” With an editor and an assistant peering over his shoulder, the Professor then states what he thinks is the root problem. “In most cases this style was simply devised as a dishonest way for cartoonists to quickly and carelessly dash together something like a bessatsu furoku.” He is referring to the 32 to 128-page insert premiums that artists took on for extra money on top of their monthly serial obligations, more on which below. “If the goal is only to increase the page count, it would be better just to draw fewer pages. On that note, let me close this month’s manga classroom with just these two pages.”

Though Tezuka could hardly have known it at the time, what we are seeing here is a line being drawn in the historical sand between the type of compressed and animated cartooning that Tezuka had been practicing, and the breakdown-oriented comics that, a few years hence, would come to dominate the field under the name of gekiga. Tellingly, the preceding chapters of Manga Classroom detail Disney-style personification of animals, plants, and inanimate objects, and the inner workings of animated movies. Stuck in between is a story about how the Professor became a professional cartoonist, which is unsurprisingly very close to Tezuka’s own. Presumably, the newness of “new expressions” is to be judged by their departure from the Japanized Disney tradition that Tezuka represented.

In 1953, the future fashioners of that new language (Matsumoto Masahiko, Tatsumi Yoshihiro, and Saitō Takao main amongst them) were still teenagers and had only begun toying with cartooning. The artists Tezuka names in Manga Classroom as practitioners of “new modes of expression” belong to a previous generation, born in the 1920s and 30s. They had sundry professional experiences as animators, illustrators, and editors, and had recently emerged as the leading lights of children’s comics. Named are: Fukui Ei’ichi, Baba Noboru, Ushio Sōji, Takano Yoshiteru, and (unable to pass up an opportunity for a self-deprecating joke) Tezuka Osamu himself.

The Professor does not say which artist employs which techniques. Use of these “new expressions” was widely shared. Many of the techniques were, in fact, most strongly associated with Tezuka’s own work, a point to keep in mind for what follows. But the three panels that receive the most flippant treatment – the “sequences like this” showing the same face in increasing close-up, the panel with “nothing but sky or clouds or smoke,” and the FX-filled “pictures that don’t make any sense” – would have been immediately identifiable by any reader at the time, whether young fan or fellow professional. They come from a manga that had, much to Tezuka’s chagrin, recently dethroned him as the industry’s top-selling author: Fukui Ei’ichi’s judo series Igaguri kun (1952-54).

Throughout Manga Classroom, the Professor repeatedly instructs kids, overtly or subtly, to draw like Tezuka. Now he is warning them, none too subtly, against drawing too much like Tezuka’s competition.

The competition took note.

(cont'd)