The following panel took place on September 13, 2014, at the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland. It was moderated and transcribed by Katie Skelly.

Katie Skelly: Hello, this is the "Sex, Humor, and the Grotesque" panel. My name is Katie Skelly, I’m just going to introduce myself quickly and then we’ll turn to the panelists. I’m a cartoonist based in Queens, NY. My first book Nurse Nurse was published by Sparkplug Books in 2012, and my most recent book was Operation Margarine, published by AdHouse Books this year.

I’m a big fan of everyone’s work on this panel and I’m so happy to be here and to be moderating, so thank you SPX and Bill Kartalopoulos for having me.

Let me introduce the panelists. To my right is Eleanor Davis. Eleanor is a cartoonist and illustrator based in Athens, Georgia. Her body of work includes two graphic novels for kids, The Secret Science Alliance and the Copycat Crook (2009), which she created with her husband Drew Weing, and the easy-reader Stinky published in 2008. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Lucky Peach, and in the comics anthology Mome, among many others. Most recently, a collection of her short comics for adults, How To Be Happy, was published by Fantagraphics Books. Please help me welcome Eleanor.

To Eleanor’s right, we have Julia Gfrörer. Julia is a cartoonist based in Concord, New Hampshire. Her work has appeared in Thickness, Arthur Magazine, Study Group Magazine, Black Eye, and Best American Comics. Her body of work includes the mini-comics In Pace Requiescat (written with Sean T. Collins) and Black Light. Her graphic novel Black is the Color was published by Fantagraphics in 2013. Please help me welcome Julia.

To Julia’s right, we have Meghan Turbitt. Meghan is a cartoonist based in Brooklyn, New York. Her self-published mini-comics titles include Conan, Becoming a Kennedy, Lady Turbo and the Terrible Cox Sucker and most recently, #foodporn. In addition to her own work as a cartoonist, she also teaches children how to draw comics, which is terrifying. Please help me welcome Meghan.

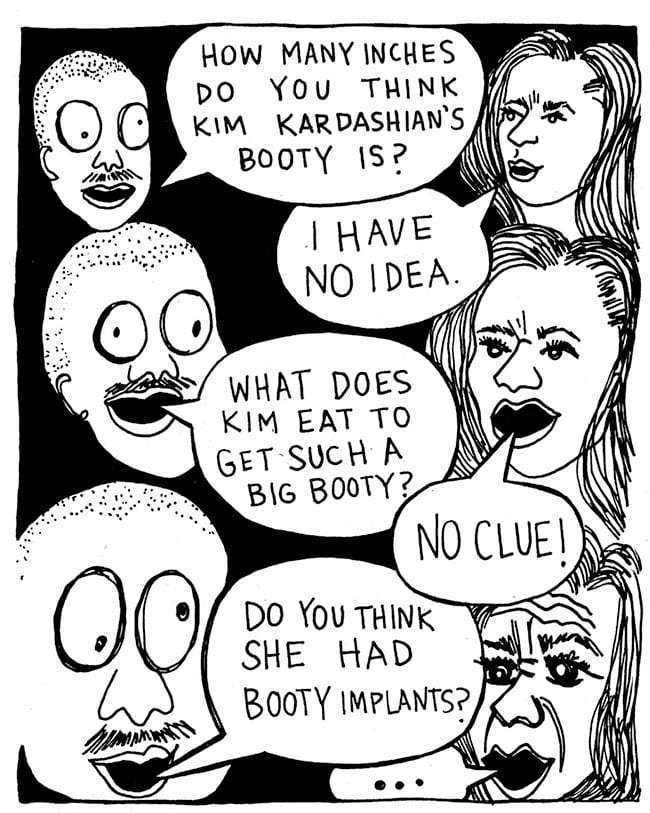

So the title of this panel is “Sex, Humor, and the Grotesque” and these are all themes that are near and dear to my heart, and that I’m interested in exploring a little bit in my own work. I’m feeling a bit braver about getting into those topics, but the panelists here are not afraid of this subject matter at all, which is admirable to me. I’m going to get started by talking to Meghan. This is from your comic, #foodporn:

Do you like calling it “hash tag foodporn”?

Meghan Turbitt: Yes.

Okay, good. This comic came out last year?

Turbitt: #foodporn [the collection] came out in April; the comic I made the previous year.

I’m going to show an excerpt from the comic in case people haven’t seen it. Meghan do you want to talk us through it?

Turbitt: This is a real—sort of—story that happened to me. I was at the local pizza joint, there was this guy making pizza and he was very unattractive except when he was making the pizza, and I was very interested in that. So I go there and I ask for the slice of pizza, and he’s super-gross and flies are everywhere—

—and then he starts making the pizza and he gets really sexy… My tongue is out of my mouth and he all of a sudden has fantastic abs and chest hair. And then—

—he feeds me. I sort of was thinking about porn when I was doing it. I was fascinated by “food porn” and I looked it up on Tumblr a bit.

Julia Gfrörer: Like, feeder porn?

Turbitt: No, like, blowjobs.

And so it’s safe to say this is a comic about you?

Turbitt: The comic is about me.

I want to talk about the look on your face on this page, because you look terrified.

Turbitt: It happened so fast! But it’s like, sometimes when you see girls in porn, they’re like that. Their faces are like that sometimes. They might be enjoying it, but they still have that look on their face.

Gfrörer: That scared look and that turned-on look are not really that different sometimes.

Turbitt: Right.

Eleanor Davis: Your toes look turned on.

Turbitt: Yeah. Curled up.

I want to go back to the compositions you decided to use here. It seems sort of like a nightmare, like everything is happening all at once.

Turbitt: It is like a nightmare. I don’t care if anything is symmetrical, I like diagonals, I feel like that’s more important than whether it’s balanced. This is actually the real pizza place; it sort of looks like that.

The other thing I wanted to talk to you about is how pop culture comes up in your work. So this piece is from the comic you did called “Kim K”—

--and that was last year, too.

Turbitt: I just printed it on its own a couple of days ago.

What is your interest in pop culture? It comes up in your work a lot, where you make references to rappers, socialites like Kim Kardashian… Are you interested in flaying it? Are you interested in celebrating it? How does it intersect with your work?

Turbitt: I’m interested in making fun of it, for sure. It’s just everywhere. I can’t avoid it. So I put myself in my comics and I think I’m just as important as Kim Kardashian sometimes. So, it’ s like obsession, narcissism, people who are super into themselves. I want to be a part of it.

Do you feel like making any kind of art can be a narcissistic act?

Turbitt: Yeah. I’m the most important person in the world, enjoying my favorite activity, drawing myself.

I asked everyone to send in different influences that they wanted to talk about on the panel. I know that Howard Stern is dear to your heart—

Turbitt: Very.

I wanted to talk a little bit about how the comedy and grotesquery of that show has influenced you.

Turbitt: I’ve been a huge Stern fan since I think 2002. I really never miss it. I started to watch the E! show with the boyfriend I had at the time and as soon as he broke my heart, I was like, “All I have left is Howard Stern!” so I became really obsessed with it. I really appreciate his honesty and reality. I want to hear about what he masturbates all day to. I want to hear what he had for lunch. I’m interested in all that. It’s sort of like a comic: you’re in his world, and you know everybody. You can be a part of it, too. You can call in, or go to Ronnie’s block party.

Right. And I think even the pizza guy you drew kind of looks like Bigfoot, from the show.

Turbitt: Yeah.

Thank you, Meghan.

So I’m going to talk to Eleanor now. This is a piece from your sketch blog, and now it’s in the collection How to Be Happy.

I have to say this was my favorite piece from your book. What I really like is the Mickey Mouse symbol on his shirt; to me that makes it so perverse. And the look on his face is deceptively simple but conveys surprise and awe. We talked to Meghan about pop culture in her work, and I’ve seen logos make their way into your work like from candy bars and Spam—what is your interest in symbols like that? Why include them?

Davis: I think one of the reasons I include that sort of thing is that for a long time I didn’t. For a long time I did things that were more mythical or set in the past, and when I would think about including things like cell phones or cars… I didn’t like it. It felt unpleasant. And then I realized that that was weird- I was trying to separate myself out from the reality that I knew by making preferable, simpler, easier, mythical worlds. And then I began adding them in deliberately a lot. I add the Mickey Mouse shirt in a lot because that particular thing symbolizes man-children to me.

Is my husband in the audience? He has a Mickey Mouse shirt, so sometimes when I’m feeling irritated at him I put it on characters.

Do you want to speak a little to the violence of this piece? It seems to be this innocent, curious act but it is destructive, and I was wondering where that comes from for you.

Davis: My husband and I have been together for twelve years, and I guess I did the piece when we were going through a rough patch. You become so much a part of that other person after being with them for so long that you don’t even feel like you can have an effect on them. Sometimes you almost want to hurt each other to feel anything because you’re so used to each other. And this piece wasn’t about him being a hurter, but it was about that sort of need for couples to have some sort of effect on one another, even if it’s a harmful effect.

To circle back to influences, I know you talked about how inserting the logos became disruptive to the mythical worlds you created. You mentioned in your list of influences Tove Jansson and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that.

Davis: She’s a super-big aesthetic influence, and also a storytelling influence, but in some ways they’re kind of separate. She does a weird thing in Moomin—the first three Moomin novels are purely pleasurable books about these characters having adventures and having fun, and being full of life and love for one another. It’s always summertime. And then in the later books it starts getting into fall and wintertime, and everybody is filled with angst, and there are a lot of storms and snow and people not being able to communicate, and it’s very depressing. And I hated those books when I was a kid.

Yeah, I was wondering when you started reading those.

Davis: I started reading them when I was little and I loved the first three happy books, and when I got to the later books I was like, “What is going on?!” I just finished reading all the sad books recently in the last month. That’s something I really like about her work, it really covers the gamut and she doesn’t just do sad and she doesn’t just do happy.

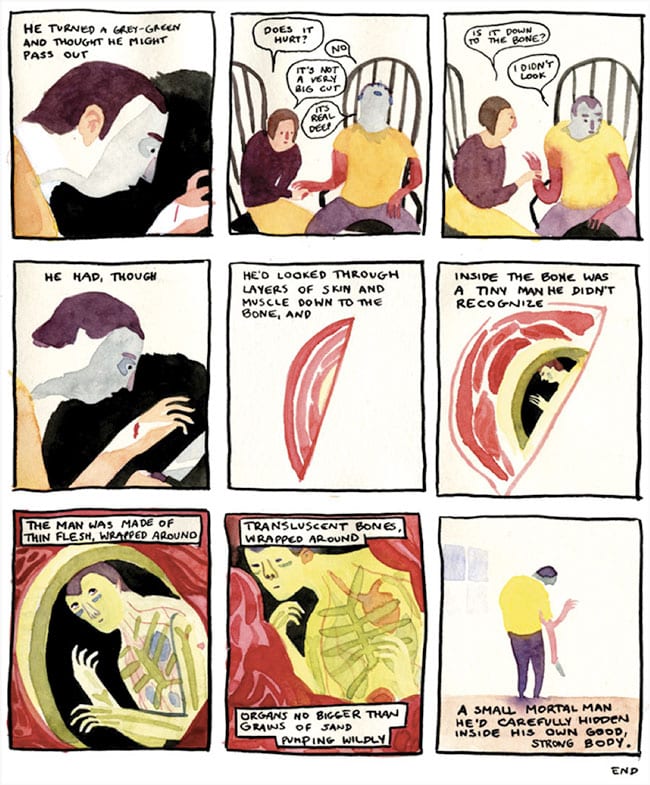

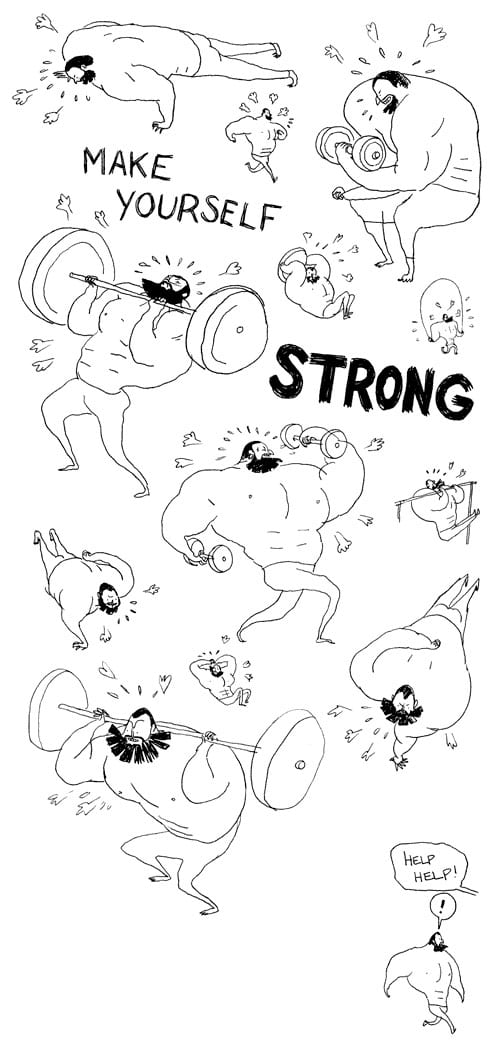

Another thing that I noticed in your work that I wanted to talk about were the references to “good and strong bodies” and I was wondering where that comes from. This is a piece from How to be Happy—do you want to describe it?

Davis: This is another comic about my husband. My husband, Drew Weing, who’s also a cartoonist, has a particular phobia of cutting himself. When he does cut himself it bothers him more than just because of the pain. I think it’s because his faith in his own physicality is shaken a little bit because he has a good, strong body and seeing a harm come to it is upsetting to him in an existential way. And in this comic he cuts himself and sees a tiny little microscopic man that’s hidden inside him.

And I love the last panel here: “A small mortal man he’d carefully hidden inside his own good, strong body.” So, I guess the idea of a good, strong body in your work is interesting to me, because in a piece like this which is also from your sketch blog—

It’s a superficial idea of a human body. It’s puffed up. Do you see him as a real strongman, do you think he could actually achieve things with his body, or do you think it’s just an aesthetic thing?

Davis: Yeah, I do. It’s a limited strength. I like bodies, I like that we get to live in them, and they’re very fragile, and they’re very temporary.

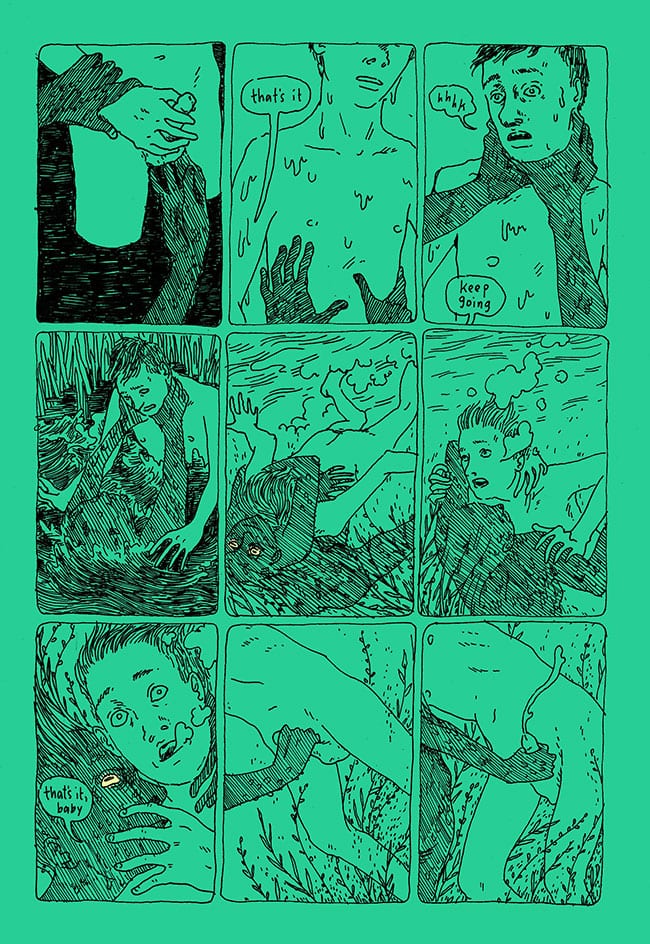

Speaking of fragile and temporary bodies, in all of the panelists’ work Julia is the least afraid—or maybe I shouldn’t say least afraid, I should say most upfront—about dealing with death. Julia when you go to broach a subject like that, when you have characters dying, characters bleeding out, what is that process like for you? Is that difficult for you to tap into? Is it something that’s kind of always at the forefront?

Gfrörer: It’s definitely very present for me in my thoughts, and it’s hard to get in touch with only in the sense that I can get stuck in it. I depress myself very easily, to the point where I’m not super functional, so it depends how much I’m able to engage with it. But things like this, this is from a comic called “River of Tears”, where there’s a woman and she’s kind of self-destructive, and maybe suicidal, and she’s freaking out. There are a lot of close-up images of her face as she’s crying hysterically. I did this at a reading a few months ago and had to simulate this hysterical crying, and it’s physically alarming to make that noise, but I have experience. And then this death character kind of comes and is so tender towards her, and she is relieved when he appears. And that’s more the death that is present in my stories- death is a relief. Death is the last best friend.

You sent me a very nice, long list of influences, but I zeroed in on Egon Schiele because he’s also one of my favorites and I’m selfish. So I was wondering if you could talk about your first encounters with his work, what you see when you look at a Schiele, and how that’s influenced you.

Gfrörer: Egon Schiele was probably the first fine artist that I really got obsessive about. I found him when I was maybe 15 or 16, when I got away from alternative music and into post-rock, and the group Rachel’s has an album that is all based on the life of Egon Schiele, and I loved the album. There are a few images of his work in the liner notes, and I got really into him. He was very young, and I was also very young. And there’s something so abject about his figures: they’re emaciated, they’re contorted, you kind of feel this desperation and this life force straining the confines of the bodies.

It’s like this visible mortality.

Gfrörer: Yeah. I wish that I’d prepared the quote for you, but he talks about that kind of luminous, corpse-likeness of his figures.

When I saw Schiele on your list I was like, I have to talk to Julia about this because I can see it in your work.

Gfrörer: Egon Schiele is kind of like a lot of people’s “my first favorite artist.” So I kind of try to not emphasize it so much, but it’s been a long time and I’ve kind of come back around on it.

Yeah. He’s cool again. Like the ‘90s. So this. I love this—

Gfrörer: I hate men.

So this is sad, but I studied art history and I don’t know if this is Judith—

Gfrörer: This is Salome with the head of John the Baptist.

Got it.

Gfrörer: This is a popular story, but I was influenced in doing this by Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, which is lovely. The premise of it, for those that don’t know, is that John the Baptist is a prophet and crazy person, just kind of famously being very outside the norm and freaking people out. He’s talking shit about King Herod and gets himself arrested, but Herod doesn’t want to kill him because he’s a holy man and Herod is superstitious. Salome in the play has the hots for John the Baptist, and everybody wants Salome because she’s gorgeous, and John the Baptist is like, “You’re a sinner, fuck your whole family.” And she’s like, “I hate you, John the Baptist, I’m going to get you for this.”

Her stepfather, Herod, has the hots for her, and he’s like, “Salome, do your special dance,” and she’s like, “No, I don’t really feel like it.” And he’s like, “Please, please do your special dance. I will give you anything you want to do this dance. I will give you up to half of my kingdom to do this dance,” and she says, “I’ll do it if you give me anything I ask.” So she does this dance, and it’s a really, really sexy dance, and he’s like, “I love this dance, I’ll give you whatever you want.” And she asks for the head of John the Baptist. So, they cut off John the Baptist’s head, they bring it to her on a platter, and she takes it and says, “When you were alive you wouldn’t kiss me, and now I can do whatever I want with you,” and she bites his lips and she touches his face and talks about how beautiful he is and everyone is like wow, Salome has really lost it. And then they kill her in the end of this play. Spoiler.

That leads me to what I wanted to talk to you about next—this is from “Phosphorus”, which is from 2013 also?

Gfrörer: Yeah, I wrote it in summer last year, and I put it in a mini-anthology that I did called Black Light, and it was also in the Study Group’s Halloween Haunting.

Something I noticed here, and feel free to correct me if I’m wrong, is it seems like when you draw these sexual encounters they’re always kind of one-sided, and it leaves the person who’s being pleasured a lot more lonely and isolated at the end of that experience. And I’ve also seen characters kind of get stained by sex in your work—like the first time in Black is the Color that the sailor and the mermaid kiss he starts emitting black fluid. In Pace Requiescat is also a sort of very lonely encounter. Do you think that that’s true of your work? Is that something you’re interested in?

Gfrörer: Well, first, of the staining thing, a lot of my work is preoccupied with residue, evidence of non-physical experiences and how it kind of erupts through to become manifest. I suppose the one-sidedness of it… there’s definitely always an examination of different types of power dynamics. Partly I think because I’m not writing about it for fun. I’m not writing about sex for it to be fun, like, “Hey guys, did you know sex is really fun? Surprise!” That’s not productive, to me. I want to find the thing that is challenging. And something like this, where it’s erotic, it could be read as porn, but to use this awful word, “problematic” ... it’s problematic. And I don’t want there to be a comfortable place where you’re pretty sure you’re supposed to know how you feel about it, because I hate that.

Right. I hate that, too. We [the audience] are smart, we can handle it.

So at this point I’m going to pose a question to the group, which is about something that I noticed as a common thread in everybody’s work—setting is negated, and we never get “this happened in this year, here’s where this is happening, here are the characters.” It’s very story-based and not so much setting-based. Do you feel comfortable with that? Do you feel that that makes your work more allegorical, and is that something you’re interested in? Does it make it more relatable, is that why that information is excluded?

Turbitt: It doesn’t matter, in a way.

Well, I know your comics are set in New York City and that they’re happening to you, but that’s because I know you. Is that important to you, does it matter if people who don’t know you know it’s happening to you?

Turbitt: It’s just like, a moment. It’s an experience, and that’s all it is. A moment of life.

Gfrörer: I think as far as specificity of location and time, I’m probably coming up with a certain time period that my comics are set in. Sometimes they’re modern, sometimes they’re vague. And I guess the reason that I would set them in a more vague period is to allay certain questions about why something is happening in a story. Like in my book Flesh and Bone, there are some children who go missing, a man gets executed, a witch is able to go to the place where he was executed- you couldn’t set that in modern day because somebody would be investigating the missing children. I mean people are investigating it in the story but not super astutely.

Right. It’s not CSI.

Gfrörer: Right. You couldn’t go collect semen from a grave site then.

Davis: This isn’t a theory that I’ve fully developed, but I’ve been interested recently in how I’m not a huge fan of short prose fiction. Maybe it’s just because the short prose fiction I read in high school was shitty and I never read more after that, but I really, really like short comics. And I think that for any kind of comics, but especially short comics, they’re a lot more like poetry. And there’s a specificity to prose that comics doesn’t have- they can be more dreamy, more surrealist, and more beautiful and trying to elicit an emotional response from the viewer in the way that poetry does.

Is that what drew you to comics initially? The ability to keep the work open-ended and dreamy?

Davis: I don’t know what drew me to comics. I think that was probably part of it, the dreaminess of it.

Julia, what drew you to comics? Why are you doing this?

Gfrörer: Looking back on it, I drew comics when I was younger, but when I went to art school I wanted to be a fine artist like Egon Schiele, and I was still doing comics on the side. When I moved to Portland I met all these comics people, and I met Dylan Williams and he asked me to do a book for Sparkplug and refined how it should be, and then that book became more popular than I’d anticipated. The positive reinforcement just kept me coming back.

Turbitt: I am funny, so comics are great for people who are funny. That’s why I do it. And also because I like to be gratified easily and very quickly, and when I was painting for years, it would take me months to finish a painting, and now it’s easy to finish one page a day in a couple of hours and feel good for forty-five minutes. And then you’re like, “Oh god, what am I gonna do next?”

And then the whole cycle starts again.

Davis: That’s a good forty-five minutes, though.

Just like this forty-five minutes, right? So at this point I’m going to open it up to questions from the audience.

QUESTION FROM AUDIENCE #1: Talking about the dreaminess of everything, when you write about these heightened sexual or grotesque experiences, how do you shred the boundaries between in some cases making it about yourself and in some cases making it completely otherworldly? Aside from getting rid of specific setting, what are some other ways you blend everything together?

Turbitt: I’m completely making them about myself so I don’t know if that applies to me.

Davis: I’m also actually completely making them about myself; it’s just that I add some otherworldly stuff on top of it.

Turbitt: I add food.

Gfrörer: I think it’s the same for me, it’s never some kind of external thing, like “Wouldn’t it be amazing if there was a world where unicorns would—"

Turbitt: Blow each other?

Gfrörer: “—blow each other?” It’s more like, I’m sulking about some kind of a thing, and it’s like, “This is so shitty, it’s as if somebody cut my arms off and threw me in a wagon and dumped me in a garbage heap,” and then I write a comic about someone whose arms are cut off and they’re dumped in a garbage heap. It’s not not about me, and the fantastical part is that the specificity of the details of my life are removed.

Davis: In a lot of places like the surrealist stuff comes in to try to explain emotions that you’re having about real life when real life doesn’t cut it. I wrote a short comic about me and my best friend, and we just call each other on the phone when we feel bad, that’s all we do, and it’s an incredibly important part of my life. So you make it into a metaphor and exaggerate it and make it beautiful so that somebody else, instead of seeing two women on the phone, they see two women who are saving each other from monstrous demons, or rescuing each other from falling off a waterfall.

Gfrörer: I say this all the time: there are certain extremities of emotion that are difficult to communicate about using literal descriptors, or the language that we have access to. Our vocabulary for emotional experiences is limited, because they’re difficult to point to, they’re difficult to relate. What I mean is, you can’t point to somebody and say, there’s your feeling, I’ve had that feeling. You struggle through this web of words to find where the other person is. So sometimes an extreme thing, a fantastical thing, is more accurate to describe that feeling. Especially to a stranger—you don’t know how I felt when I got laid off from my job, but you know how it would feel to get throw off a boat in the middle of the ocean.

QUESTION FROM AUDIENCE #2: You guys have all mentioned fine art and fine artists, and I wonder if there are any other comics people who really specialize in the grotesque who were influential, or whose work you see yourself as enlarging on?

Turbitt: I was super into Ariel Schrag when I first started reading comics, and her storytelling and self-importance was very influential, and some of the gross sex stuff that was going on in those comics I relate to and was inspired by.

Davis: She’s a contemporary so it seems silly to say that I’m working off of her stuff, but I really like Lisa Hanawalt’s stuff, and her stuff tends to be funny, but it also feels really important to me. Her work makes things easier for me in how balls-out she’s willing to be, and that’s very inspiring.

Gfrörer: I was really influenced by Al Columbia. He was maybe the first person whose comics I’d seen where his comics are so upsetting. They just do not hold back at all, and when I first saw his work it was in The Stranger when I was living in Seattle, I was just like, “How was this even a comic?” I was 20. And it just had never occurred to me that somebody could be so relentlessly bleak and so unapologetic. And it was so exciting to me.

Davis: Dave Cooper, too.

I read Ripple when I was 13 in the comic book store in the section I wasn’t allowed to be in, and that was when I was like, “This is what I have to do.”

QUESTION FROM AUDIENCE #3: Kind of a generic question, but if you couldn’t emote your stories through the comic book medium, what else would you work in?

Gfrörer: Is there a reason in this narrative that we’re not able to make comics any more?

Turbitt: I would like to do comedy, and I did it for the first time a few weeks ago. I didn’t tell anybody, but I did it. So I’m thinking of trying to do more performance stuff, like slideshows with my comics. That’s what I’m into.

Gfrörer: I think I would be a prose writer. I started writing a column for The Comics Journal and I’m really into that. I tend to not like my prose voice as self-expression because it’s didactic. It’s pretty stodgy sounding, and I tried to overcome that and it sounds false, but maybe if I did it a lot I’d get over that.

But do you find that that’s helping you with your process of drawing now?

Gfrörer: I guess so. The kind of analysis that I’m doing for The Comics Journal—the column is called “Symbol Reader”— it’s a kind of analysis that I do anyway, so I would have been doing it anyway. I feel like it helps me think about my own work.

Davis: A side hobby that I have is making art dolls. And whenever I’m feeling bummed about how hard comics and illustration are, I think about how fucking hard it is to sell a $200 art doll. Which I’ve never actually done. I’ve tried. Nobody wanted it. My new calling is doing avant-garde slideshows.

Fantastic. I want to say thank you to our panelists. Thank you, Eleanor Davis, Julia Grofrer, and Meghan Turbitt. Thank you so much everyone.