John Porcellino, born in 1968 and raised in a suburb of Chicago, where he developed a fear of muskrats and squirrels, is best known for King-Cat Comics, the autobiographical zine that he self-published starting in 1989. Porcellino, who went to art school at Northern Illinois University, has had many strange jobs in his life – holding up oriental rugs for auction; chopping up furniture in an old farmhouse and setting it on fire; smashing a limited edition of collectible porcelain dolls. His books include Perfect Example; Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man; Thoreau at Walden; as well as two volumes of his King-Cat comics, King-Cat Classix, and Map of My Heart.

John Porcellino, born in 1968 and raised in a suburb of Chicago, where he developed a fear of muskrats and squirrels, is best known for King-Cat Comics, the autobiographical zine that he self-published starting in 1989. Porcellino, who went to art school at Northern Illinois University, has had many strange jobs in his life – holding up oriental rugs for auction; chopping up furniture in an old farmhouse and setting it on fire; smashing a limited edition of collectible porcelain dolls. His books include Perfect Example; Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man; Thoreau at Walden; as well as two volumes of his King-Cat comics, King-Cat Classix, and Map of My Heart.

His new book, The Hospital Suite (Drawn & Quarterly, 2014), chronicles the excruciating events in his life beginning in the summer of 1997. That year Porcellino, while living in Denver, began having stomach pains. After many tests, his doctors discovered an “abnormal growth” in his abdomen. Once that was removed, Porcellino and his wife, Kera, moved back to Elgin, Illinois, the town that Rosanne Barr made famous. There his mental troubles began to take over his life. A cruel case of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) ruled what he could and couldn't do or draw and what he must do over and over. His marriage broke up in 1999. For a while, he lived alone with his cat, Maisie Kukoc. Finally, he moved back to Denver, then to San Francisco, with Misun Oh, his acupuncturist, who became his second wife (2003-2010). For 17 years (1997-2014) he worked on and off on The Hospital Suite.

Porcellino now works as a janitor and lives, with his girlfriend, two cats, and two dogs, in Beloit, Wisconsin, almost within view of his beloved Illinois. (“I can't see it,” he said, “but I can smell it.”) I spoke with him in his hotel room at the North Bethesda Hyatt, room #307, two days after the Small Press Expo had debuted an independent film about Porcellino, Root Hog or Die. – Sarah Boxer

Which is more fun to draw – physical illness or mental?

With physical illness you get to draw barf and stuff.

You like drawing barf?

Kinda, yeah. It's expressive, it's very visual. You can have a lot of fun with it. You can draw ripples and particles and occasionally you get to draw a toilet.

How about mental illness? In some ways, that's more fun for the reader.

As much as the book is grueling I hope there's some entertainment value in there too. I try to pack some big laughs in there. My comics generally are about being honest, whatever the situation may be – great or terrible. I've always been comfortable writing about my depressive tendencies, but the anxiety, the OCD and stuff – it's so fraught with tension and fear that it was just really hard to express. In King-Cat Comics, my little zines, I would reference it, but pretty obliquely. There'd be little comments here and there, if you were paying attention, you might pick it up.

Where in King-Cat do you talk about your OCD?

In my book Map of My Heart, there's the bird story. I kind of talk about this bird and I see this bird and then it cuts to this panel – it's just me at my drawing table – and there's a look on my face, of fatigue or misery – and the text is: “Lately I've been struggling.” I remember when I wrote that, those four words encapsulated all the suffering of those four years.

That was the extent to which I could let loose what I was trying to say. I remember thinking then, that's not like the stuff in the other issues. It was all true but I was holding back. The OCD was holding me back. When I was in the grips of the anxiety, well, it just frustrates whatever you want to do. I wanted to express it. But the OCD would find ways of throwing me off. …

What do you mean? Did you draw comics and tear them up or could you not even draw?

I would get an idea and start it. OCD is insidious. It was like, you can't say that. I had a lot of – there's these subsections of OCD -- there's this thing called scrupulosity. It focuses on religious, ethical, and moral things, like you get hyper-religious. So I have all kinds of thoughts like, “If I write this comic or publish this comic, I'll be punished, God will stop loving me.” Or there will be these terrible consequences. Some of it I did put down on paper but I just lacked the will to actually publish. Sometimes I couldn't even get pen to paper. The OCD made it impossible to talk about just about anything, let alone this crippling illness that I felt deeply ashamed of.

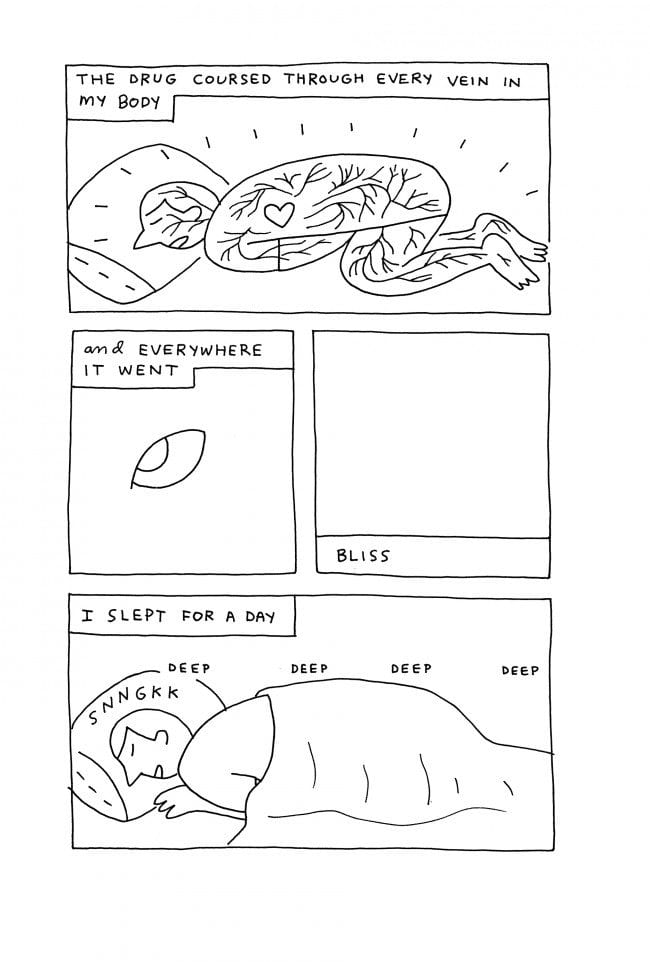

With The Hospital Suite I finally got to the point where I could talk about that stuff not just emotionally but my brain was in a place where I could express this stuff. I was ready to do it. Enough time had gone by. I had finally worked out the pharmaceuticals and supplements to kind of get out of the grip on it. But it's a process. I still have weirdness, sure.

You wouldn't be doing comics if you weren't weird.

Yes, I've often said, somebody somewhere should do a research paper on cartoonists with OCD.

Who would you put in that book?

Who would I put in in the OCD book? In the club? Let's put it this way, when you have that kind of anxiety you become very perceptive of that anxiety coming off other people. I can sense it when I meet people. It's like ESP. I can see the way I act because of this disorder and I can see this manifesting in other people's actions. It's not like I'm sitting here diagnosing people, but when you have OCD you notice everything, you're hyper-aware.

So cartoonists know who the other OCD cartoonists are. Are there a lot of them?

Well, sometimes I'll be talking to some cartoonist and he'd be saying, “Yeah, I have that too.” Pretty, soon it went from being like “Wow, you too?” to being like, “Of course you do, you're a cartoonist!”

Why are cartooning and OCD so closely entwined?

It's like a vicious cycle. It's probably that the obsessive-compulsive personality lends itself to cartooning and cartooning lends itself to OCD behavior. And this is not true for all cartoonists, especially not nowadays, where you have these wild styles. But so much of cartooning is about hiding your mistakes. You do these drawings on paper with pen and pencil and they don't come out right. The pages are covered in white-out and masking tape, you cut and paste new paper down over the bad drawing, and God forbid that any of that shows.

I can see that with someone like, say, Chris Ware, but so many cartoonists flaunt their mistakes now.

Yeah, people are drawing with pencils and leaving the eraser shavings in the finished drawing, and so that's probably a healthier way to be a cartoonist than desperately trying every trick in the book to prevent the finished product from having any sign of imperfection. Ivan Brunetti, my friend the cartoonist, he always used to say that cartoonists take the whole world, their whole life, and they try to cram it and fit it into these little tiny neat boxes.

Do you think OCD has something to do with clear-line cartooning, with the obsessively neat lines of someone like Hergé?

Certainly stuff like Tintin. It's so fanatically precise, right? My comics are very minimalist. They look very simple – like a drawing could be just four lines -- but it's not really that simple. When your drawing consists of four lines, those four lines had better be in the right place. Right? There's nowhere to hide. There's no distraction in that drawing.

But somebody like Gary Panter, I'm guessing – you know he's got these ink thumbprints and scratches all over his drawings – it doesn't seem that he's OCD. But then people can be pretty good at hiding it. In my personal appearance I'm not at all OCD. I'm like a total slob. Every person that I've ever co-habited with has said, “Why can't you have the kind of OCD where you have to pick up every little speck off the ground and wipe the counters twenty times a day?”

I'm curious about the editor's notes that you put in. Those are yours, right? There's no real editor.

It's me. In old comic books from the '50s or '60s, whenever they had an aside, like at Marvel Comics, Stan Lee used to put his thumbprints all over all the stories and they kind of break that fourth wall, or whatever you call it. Stan Lee would be like, “Spidey's swinging his way across Manhattan on his way to meet Mary Jane.” And there'd be a little asterisk, “See last issue. ed.”

I love the little hearts you put in.

When I draw the heart, usually it's to show a feeling of overwhelming love or bliss or overwhelming emotion. It's not always 100 percent love or positive. But it's trying to expresses this inexpressible emotion.

You wrote The Hospital Suite long after your illnesses? How did you remember the events and the feelings? Did you base it on the King-Cats you wrote at the time?

The Hospital Suite, that first story, takes place in June, July of '97. When I was in the midst of it I didn't know if I was going to live or die so I wasn't necessarily thinking of making a comic. But I am at this point kind of conditioned to keep track of things. Shortly after I got out of the hospital and had the surgery, once I realized, I guess I'm gonna survive, I pulled out a notebook and drew a calendar and I wrote down: this is the day when I had the barium x-ray, this is the day I had the colonoscopy, this is the day they discharged me for the first time; this is the day my stomach started to hurt again. ... Generally, my working method is that I just have notebooks and I'll put in little memories, stories. And you know I make a lot of lists...like a good obsessive compulsive.

Speaking of lists, I noticed a lot of jazz figures – Sonny Rollins, Ella Fitzgerald – on your top-ten lists. That's pretty unusual taste for someone growing up in the 1970s. I mean Bill Evans! Really?

Bill Evans. There's probably few musicians out there where my brain functions on that level, where that's like a seamless entry. I'm not saying I'm a genius like Bill Evans. But Bill Evans, whatever his music is, it's like the soundtrack of my brain.

Mmmm. So back to The Hospital Suite.

So yeah, I have these notebooks and I'll fill them up. Little bits of dialogue. Memories. I'll write out a little stories and they stack up. I wrote down everything that happened. And maybe every couple years I'd pull it out and work on it. Mostly I'd just write until the story was at a point where I felt it was time to start drawing. I'd refine the story and draw and edit and adjust and maybe put it down for a number of months or years.

When I signed the book at the end I think I wrote down 1997 to 2014. It's not like I worked on it every day for seventeen years. Maybe every three or four years I'd have a burst. I always knew that somehow, somewhere, if I survived, if I lived long enough, I would write about this stuff.

There are three different illnesses in The Hospital Suite, right?

The three stories in the book The Hospital Suite were always written as three independent stories, even though they overlap and tell a larger story. I always worked on them independently, I envisioned them as three little novellas. But I didn't want to be that guy who every year or so says, “Hey, you liked that tale of misery and woe? Well, here's another book about something terrible that happened to me!” And once I started envisioning how this would work, I realized they all go together.

Why are so many comics about illness and death – Harvey Pekar, Joyce Farmer, Roz Chast, now you?

We're all getting to that point where people are dying around us, and we're getting sick, and our indestructible youthful bodies are beginning to show signs of decay.

And why are there so many graphic memoirs?

I'm certainly not the first to do it. When I started doing it, there was Robert Crumb, and Justin Green had Binky Brown, and Dori Seda. It's not like it was new. But I would not have foreseen how it would become this huge thing. It was just a surprise. Not that it's all unpalatable. I like reading stories about people's lives. Not only do I make these comics but they're my favorite comics to read. Even when I read books without pictures – I do read those occasionally – I favor biographies and autobiographies; I'm interested in books about real life.

You mentioned Harvey Pekar and his book My Cancer Year? How would you compare your books?

I don't compare myself to him. No. I don't want to do that. One of my little tidbits of advice I give to younger cartoonists is: Don't compare yourself to other people. You will always lose that game. There's always somebody you're going to crumble in the face of. And you don't need that as an artist, that pressure and doubt. Your job an an artist is to to bring what's in you out. We all have our idols – cartoonists and writers and musicians and artists that we're in awe of.

Who are you in awe of?

I just got to have dinner with Lynda Barry. A few years ago she was at the University of Chicago and she was sitting on a panel with R. Crumb and Charles Burns, all these genius cartoonists, with an audience full of people listening to her. And she said – and I'm paraphrasing and probably butchering what she said – What a beautiful thing that I get to be with all these amazing people simply because I drew pictures! So I was sitting here talking with Lynda Barry. At some point in the evening it washed over me: “This is the person whose comics, when I was 15 years old, I used to tape to the fridge! And now I'm having dinner with her and talking with her about comics and life. What a fantastic stroke of luck or whatever it is!"

What do you think you would have become if you'd been born twenty years earlier?

As terrible as the world is that we live in, I've always felt pretty clear that I'm glad I grew up when I did. I got to experience all the things I needed to experience and be part of – zines for me and like punk. I guess if I'd been born forty years earlier, I might have been a beat dude. I certainly wouldn't have been a normal person. Every decade has their group of you know...

Off-center people? Would you have done both drawing and writing?

I would probably have done both drawing and writing. I've always loved drawing, I love books, I love reading, I love the form of pages, I love pages, I love newspapers, I love paper. It was natural for me to become a cartoonist. It combined all those things that I loved. As a tiny kid my earliest memories were sitting at the kitchen table. I was always drawing on the back of scraps of pages and folding them gluing them together and making books. When I was in high school I took every art class I could. When I was in college I was an art major. I was always doing these little books.

From what age?

I would guess the first little book I put together was when I was 6 or 7 years old.

What kind of comic books did you read?

I never really had exposure to comic books. I'd get on the train to go downtown and at the platform there'd be a stand where they'd sell cigarettes, gum, and comic books, and every once in a while I'd get one of these comic books to read on the train. This was like the early '70s, this was after the Comics Code had relaxed.

But you were only 5 or 6 years old.

It was '73 or '74. So I read scary stuff, vampires and Werewolf by Night and monster stuff. I had one superhero comic. I think I had two. This must have been 1976. I had the Superman comic where where Clark Kent gets punched so hit so hard that he goes back in time to 1776 and meets Ben Franklin and has to like save the Revolution. I would have been seven years old. Of the seven comic books I owned, maybe five of them were like monster stories or ghost stories.

Did you read comic strips too?

My dad would bring home the paper. We got the Chicago Sun-Times. But the Chicago Tribune had a hold on all the classic comics – Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, Peanuts, Li'l Abner, Moon Mullins.

What did that leave for the Sun-Times?

It left Marmaduke, it left Cathy, it left Miss Peach. Tumbleweeds.

Couldn't you ask your dad to get the Tribune?

Well, the Sun-Times was like the people's paper. My grandma got the Tribune on Sundays, though, so when I visited her, I'd get to read all the Sunday strips. That was my only exposure to Peanuts – the Sunday strips, the television specials, oh, and I think a cousin of mine had those paperback collections.

Poor you!

Miss Peach, you can't go wrong! Tumbleweeds. It's good stuff! Very grotesque drawing, Wild West. I think Big George was in the Sun-Times. I like comics, even the bad ones.

So which strips did you really like? Or do you still like?

Ziggy! I had a Ziggy mug: Ziggy's in his nightcap and he's opening up the curtains on a new day and the sun is sticking his tongue out at him. I formulated my world view early on in large part due to Ziggy.

You don't use a lot of color. How do you feel about color?

Color is a tool of the man.

What does that mean?

You don't need color. Color is a distraction. It's giving into the spectacle. Black and white contain all the colors.

Are you serious?

I'm 51 percent serious.

Tell me about the 49 percent.

Obviously I like colors. I like to look at colors. Why do you think USA Today is so popular? Do you remember how groundbreaking this was? Color?! [He holds up a copy that was delivered to his hotel room.] But for me personally, color is kind of extraneous. I do use color occasionally. The letters on the cover of my new book are orange. But no, seriously, I do believe color is a tool of the man. It's just an extraneous luxury.

So would you prefer the world to be in black and white?

No no! I'm just talking about me. Always with my comics, what I'm trying to do, is to put down the thing that's in my head as straight as possible. When I draw a page of comics it doesn't need any color. Color would mess it up. In the olden days if I drew a scene at night, I would take some ink and fill in the sky black or use cross-hatching, but at some that even became unnecessary. There's context there probably that tells the reader that it's night. The reader already knows the night sky is dark. I don't have to draw the darkness.

That's really extreme.

I'm not trying to accurately render the world, I'm trying to transmit something from my head into another person's head. You don't necessarily need a lot to do that. When I talk to students I tell them cartooning is like writing. Even the drawings are writing. The letters CAT, they don't mean anything. They're abstract lines on paper. You learn through the process of reading that CAT is a symbol that represents the furry thing throwing up behind the couch. If I can drawn a car with three lines and the person can read it as a car, I'll use three lines.

Sometimes I still get that cliché, “My five-year-old could draw this.” I think to myself, “I'd like to see your five-year-old draw that!” I still get that. Reviewers will be looking at my comics and they'll say, “But you can really draw right, can't you? I mean, you could make this look good, right?”

Has your language evolved?

Sure. You know Ziggy taught me. Tom Wilson [creator of Ziggy] taught me. Brad Anderson [creator of Marmaduke] taught me. To a certain extent, the way I draw even now is kind of the way I drew when I was seven years old. If I drew a face I would draw an oval with dots for eyes and a little shape or a nose and a line for a mouth. But you make happy accidents. You just learn over time. So certainly there's been an evolution.

How would you characterize the evolution?

I think it's been an organic natural refinement. But I never had an agenda – comics should be like this. I just drew. My agenda was not to get in the way of my comics. Sometimes even now, I'll draw a comic and I'll feel compelled, I do need to shade in the sky. I just want it to be what it wants to be.

Tell me about Maisie Kukoc, your cat, who appears on many pages of The Hospital Suite. She couldn't still be alive, could she? What does “Kukoc” mean?

Maisie's nickname, Kukoc (pronounced Ku-coach), comes from Toni Kukoc. He was a member of a couple of the Chicago Bulls championship teams – “The Croatian Sensation.” I named my cat Maisie but at some point it was clear that her surname was Kukoc. She was my cat for seventeen years. She lived a long hopefully happy life. I tell the story of what happened to Maisie in King-Kat #68.

She was originally my friend Donald's cat. I met her when I went out to Denver in 1992. He would go off to work. And I would be at home working. She was still a kitten. She just imprinted on me. She was tiny, just a runt. I would be drawing at my drawing table. And she would climb up on my shoulder and sit there like a pirate's parrot. I could get up from drawing and make lunch and do the dishes and she would still be on my shoulder. We just became inseparable.

King-Cat #75. That's going to be Maisie's life story. My original outlandish hope was that I would have King Cat #75 out for the show here. But it became clear that I wasn't going to get it done. I'm giving myself until May 2015 to get it out, King-Cat's 25th anniversary. I want issue #75 to come out that year.

How long does each King-Cat take to make?

The first two years [1989-1990] I did like two a month. I was cranking them out. It was all completely spontaneous. Something would happen, I would like draw a comic and put it in the done pile, and when twelve pages were done I'd make copies, twenty copies, and sell them.

How much did they cost?

Thirty-five cents.

Wow. How did you make the change from 35-cent copies to books published by Drawn and Quarterly?

I've had two episodes of gumption in my life. One of them was in the late '90s. This friend, Tom Devlin, who was a big supporter of my work, worked in a store called Million Year Picnic in Cambridge, Mass. He would like order lots of King-Cats for the store. Then he started a book publishing company called Highwater Books. This was when people started to have the idea of graphic novels, putting comics in more permanent form. He was one of the first people to do this.

What about Art Spiegelman?

I loved RAW. I loved anything that was weird. What happened in the late '90s was there was this generation of self-published zines. But in the comics world there was a stigma against self-published comics, as if they were not good enough for publication by a “real publisher.” I came from punk rock, a complete DIY attitude – You're in a band, you put out your own records; you're a cartoonist, you put out your own comics. I came from a wave of cartoonists who came from that perspective.

Some of their work was good enough that the comics world had to grapple with it. Tom at Highwater was bringing some artists from that world and putting them in formats that were more palatable. He used nice paper, beautiful inks. His books had covers that were not glossy or gloppy and they had wonderful textures. He was one of the first to present comics as art, but in a different way than RAW.

What was the difference?

The reason I was drawn to comics because they were the antithesis of fine art. They were junk culture -- disposable, cheap, accessible, affordable. It was like a sneak attack on art. I think Art [Spiegelman] and I would agree that comics are art. But I wanted to go under that world. And around it. I wasn't even interested in engaging that world. (I'd love to sit down and talk with him about it.) That's why I was drawn to cartooning. To me, they were an art form that was ubiquitous, but because it was ubiquitous, it was invisible. Like a submarine. Tcchh, Tcchh, Tcchh, Tcchh. And then all of a sudden, here I am! Look at this thing!

Back to your moment of gumption.

I had just drawn the comics that became “Perfect Example.” I had just done this 72-page story and Tom had just started Highwater. So, I approached him: Do you think this would make a good book? And he was like, “Yeah, sure!'

Okay, that's one episode of gumption. What was the other one?

After Highwater had run its course and Perfect Example had gone out of print, I knew Tom wasn't going to be able to reprint it, and I wanted it to stay in print. So, I was at a show in San Francisco, and D & Q was there. I approached Chris Oliveros. I said, I have this book. Highwater put it out. There are X many copies. And it's out of print. I had to be pushed. Of course I don't like to do this. I'm a good mid-Western boy. It took a while. But they said yes. So it 's worked out. It's hard for me to muster that kind of courage.

What artists were you into when you were at Northern Illinois University?

What artists were you into when you were at Northern Illinois University?

This was the 1980s. I was really into the German Neo-Expressionists – Baselitz, even Anselm Kiefer. I liked figurative stuff and these people were bringing it back.

And before that?

In high school -- I really have to mention them because they get short shrift – the Chicago Imagists, people like Jim Nutt and Christina Ramberg. I had a really hip teacher and she showed slides of the Imagists. Funky, comic book inspired, advertising inspired art. I was immediately drawn to it. They connected comics with painting and storytelling and it was figurative and funky and weird. Lynda Barry, Matt Groening and the imagists – Put those three together.

But in terms of fine art it was the Neo-Expressionists. And Matisse. Just the line. And the color and drawing. I could just look at a Matisse painting all day, just melt into it.

Anyone else?

There were a couple of cartoonists in the underground. Jenny Zervakis – she did a comic called Strange Growths that was really poetic, vague, otherworldly – immensely influential for me. Another zine person -- Jeff Zenick. He famously in the '90s, rolled up a tent and rode his bike around the country. He'd like set up his tent near a Walmart and live in some town and draw portraits of people and sell them on the street. He was also famous for having a job that was literally shoveling shit at a water treatment plant. His zines were very simple, everyday life, but also incredibly deeply beautiful, spiritual. There would be a drawing of street scene of some panhandle Florida town and at the bottom would be like an quote from Emerson. I was on a directional path similar to them, but when I discovered their work it would reinforce was I was doing – poetic, direct and honest, no frills way of making art.

Is drawing meditative for you?

Oh yeah. I think any activity that you lose yourself in is like that. Sports like running, any kind of thing where your mind lets go of its grip a little and you just act. Of course there's sitting meditation and that's different. But still it's letting go of the grip that the mind has. That can happen with doing the dishes. You just lose yourself.

Did meditation and drawing help you out of the OCD?

Meditation had immense benefits. Drawing too. But when the OCD got really bad – and I guess this is my other moment of gumption, well, it wasn't even gumption because my first wife, Kera, said you have to get therapy, you have to get on meds. I was on meds and they relieved my anxiety. But the side effects were almost as disastrous. I was on meds for a year an a half and then I spent a decade off pharmaceuticals. I discovered zen. And I tried meditation.

I just didn't want to be on drugs. I'm a good mid-Western guy. I don't want any help. I don't need any help. I'm gonna quietly just deal with this by myself. I felt it was my responsibility. So I tried exercise, eating right, being out in nature, meditation, and yoga. All helped to some degree. But OCD is insidious. It's like a whack-a-mole. Knock one down and another pops up over here.

Did you have OCD as a child?

I'm a textbook story. I had these predilections as a child. Obsessive compulsive traits. I was scared of a lot of things. And then when I was at college, boom, it popped up again. Then it would disappear for six months. Always just kind of an annoyance. But when I had the health crisis, looking back on it now, I feel like the really ugly OCD that popped up was a post-traumatic stress reaction to the physical trauma. I mean they cut you open and rearrange your organs. Whether you're happy about it or not, the body responds to the trauma.

How is it for the people you know to be characters in your comics – for instance, Kera, your first wife, and Misun, your second?

I'm still in touch with every person I've ever been close to. I do use them. I have access to those people's memory banks. But just out of respect for them, I always ask, “I want to do this story. How do you feel about that?” But also as an investigative person. They always remember stuff I don't. They have points of view that can be helpful. You know, I'm not vindictive. I'm not out to do revenge comics. I'm pretty careful and thoughtful. Just because I'm a cartoonist doesn't mean that everybody around me wants to be the subject of a public expose.

Why do you need to use their memory banks? Aren't your books about your memories?

I think my early comics I was very concerned with the journalistic truth. I was trying to get at the facts. I wanted everything to be accurate, honest. It was a breakthrough for me as an autobiographical cartoonist when, while doing the Perfect Example stories, when I went back and contacted a lot of people from my high school days, I realized that every one of these people could tell the story differently.

Kind of like Rashomon?

It switched for me from this idea of journalistic truth to all I can really write is my own truth. Like I said, I talked to people and I put in things that I don't even remember happening and it added a certain depth to things, but it's my own story. I don't mean that in an egotistical way. But it's the only way. I'm not a journalist. I can't tell these things objectively. There are objective portions, but ultimately, it's my story.

Tell me about the King-Cat logo. Why is the cat's scepter always changing?

The scepter is waving, blowing in the wind. The inside of King-Cat Classix has a whole grid of King- Cats. I was looking at them last night. I draw the same cat, but they're different every time.

Your King-Cat kind of reminds me of Ignatz Mouse from Krazy Kat when he's a king in an ermine robe.

My thought is he's kind of like Ignatz leaning in his jail cell. George Herriman was the greatest cartoonist of all time probably. I do understand people who are like, “I just don't get it – it's the same thing over and over again.” And Nancy is the same. But he is in complete control over this world that he has uniquely created. For someone who's interested in repetition, minutiae, and details, boredom, where nothing is happening, you really get to see what's happening. For the 40-whatever years that he drew that strip, he was constantly finding new ways to nuance that love triangle. It's so funny and weird and precise and endlessly inventive. You dig into it, and this whole thing unfolds. It's genius. It's really what you would call genius.

Tell me about the words “Root Hog or Die,” which is the title of the film that was just made about you and which you also use sometimes in your comics.

“Root hog” is my affectionate name for a woodchuck, Marmota monax, whistle pig, prairie dog, groundhog. It's hard to say its my favorite mammal, because I love cats, I love dogs, I love birds. But I do get a thrill out of a root hog. Maybe it's my totem animal. And then there's the all-American phrase: “Root hog or die”. Farmers would be raising hogs and they would let them go run out in the woods to forage for food, and they'd say, “Root, hog, or die.”

For me, Root, hog, or die! means: Fulfill your destiny. Do it yourself. Take on this responsibility for yourself. When I heard this terminology, it had a lot of connotations for me and for my beloved DIY culture. Do it yourself. No one else is going to do it for you. No one should do it for you. Take responsibility. If you want to do something, do it. It was my attitude toward sickness. It's my attitude toward life. It's kind of my motto. In moments of toughness, I will actually think it to myself, “Root, hog, or die!” It emboldens me a little bit.