What you see above was printed on the back of every press pass. The passes, as is usual for the Small Press Expo, dangle on lanyards around the necks of attendees, and have a tendency to flip themselves around throughout the day. I presume the joke intended by Shannon Wheeler, the cartoonist, is that the wearer will not notice their badge flipping, and unwittingly display this special message to anyone they're shaking down for goodies. It's an old comics culture joke. Anyone who's attended enough conventions in a professional capacity has at least one story of some foxy rando maneuvering his or her way past the paid admissions and cashing in on swag through dubious press credentials; I've certainly encountered my share of "is this a real website?" situations in even the few big-time geek culture shows I've managed to attend.

Does this joke apply to SPX? Most of the press people I met last weekend did not seem to agree, though at the same time I must confess I've already heard a few stories about exhibitors suffering through offers of riotously uneven book trades and other small perils of life in a clubby, artsy community. Perhaps this hint of opportunism, branded upon so many comped admissions, only confirms the belonging of the press in a delicate ecosystem plentiful with cricketing species. "Everything," it chirps, "eats everything."

And everything can be found these days at SPX.

***

11:00 AM: I-270 approaching Bethesda/(the World Class) Marriott Bethesda North Hotel & Conference Center Grand Foyer/the Grand Ballroom aka "the show floor"

I was in trouble. No sooner had the day begun than I'd delayed my traveling companion, Chris Mautner, leaving him seated in front of my apartment for twenty solid minutes while I scrambled to find a hilarious prop minicomic I'd cobbled together for a series of Twitter jokes cued up the evening before. My show prep probably should have consisted of more than giggling to myself in the parking lot of my office building at sundown while typing about farts in all caps, but I was planning to rationalize such behavior as my own small contribution to the punkish irreverence endemic to the alt-as-fuck small comics press.

Except: I wasn't seeing any "SPX people." There's usually not a lot going on in Bethesda, at least in the area surrounding the Marriott, so you can generally spot a potential attendee by their mohawk as soon as you're off the highway, but this Saturday there was nothing. It was raining. The TopatoCo van, smiling bravely in the parking lot, was the only clue that the con was even happening.

Immediately upon entering the hotel -- and this was not an impression that subsided as I collected my badge, chuckled at Mr. Wheeler's good humor, and entered the show floor -- I noticed that the crowd seemed more diverse than ever before, and by that I don't just mean there were as many women as men (although that, as usual for SPX, was true); there were a *lot* of younger teens, kids with parents. Attendees over the age of fifty. Average folk. Usually, in spite of my attendance at the show for nine years' running, I'd expect to feel at least a little out of place, given my tragicomic haircut and the oversized long-sleeved shirt I'd grabbed at random when I'd noticed it was chilly that morning, giving everyone pause for a moment to ascertain whether I'd come to the show in literally my pajamas, but by god I suddenly felt normal.

As a result, I immediately wondered if alternative culture was dead.

***

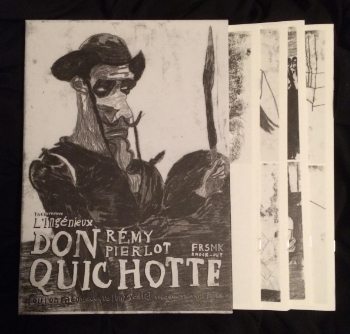

The Ingenious Don Quixote (L'ingénieux Don Quichotte)

By Rémy Pierlot

Frémok, 22€, 100 pages

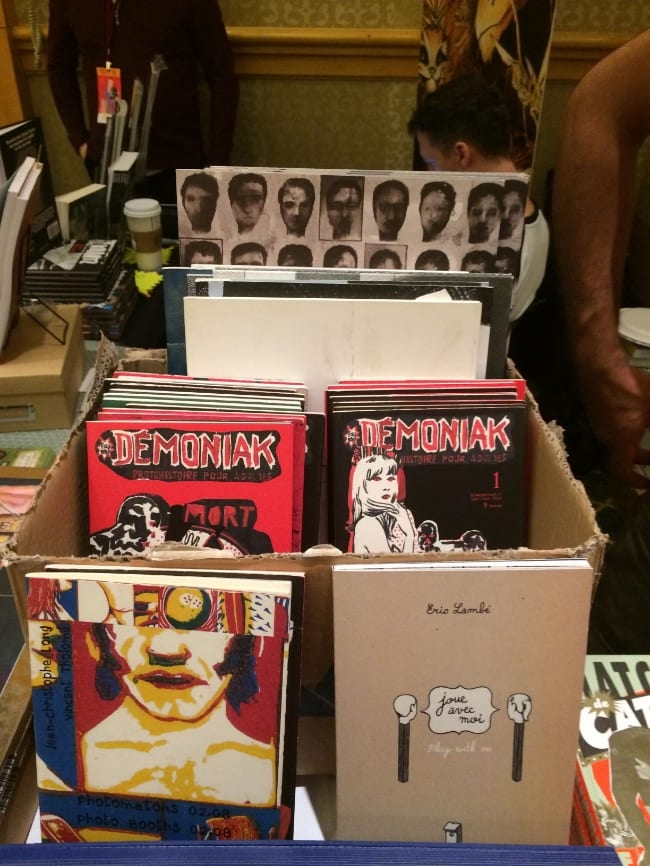

First stop: Frémok! Yvan Alagbé and Dominique Goblet of the revered Franco-Belgian experimental comics group had schlepped all the way across the Atlantic for this show, as the publisher had done at MoCCA roughly five months earlier, although I did not recall their NYC table sporting the valuable attribute of going 1:1 euros-to-dollars for every cover price. As a result, I wound up introducing the French delegation to our founding father, Benjamin Franklin.

This is among the newest Frémok releases, one of relatively few French-English bilingual projects, and comparable to some recent American releases insofar as it's actually a package of smaller comics by a single artist that can be read in any order to form a 'book' that's more of an impression. Building Stories is the AAA example, though smaller presses and individuals have gotten some good effect from the approach, like the Katz Sisters' excellent self-published The Night Poetry Class in Room 1001 (admittedly a little more chronological). Don Quixote, specifically, is eight 7.5" x 10.5" stapled comic books, 8 to 24 pages in length, housed in a slipcase.

The artist is Rémy Pierlot, who has contributed to two earlier Frémok publications; from what I can gather, he is mentally disabled in some manner, and his participation comes through a Belgian arts center, La 'S' Grand Atelier, which has collaborated with Frémok on a small line of collaborative works with disabled artists. There is, notably, a "Montage et supervision" credit on the slipcase, with Frémok co-founder Olivier Deprez listed among the contributors, which suggests that some manner of image arrangement was carried out by these additional parties.

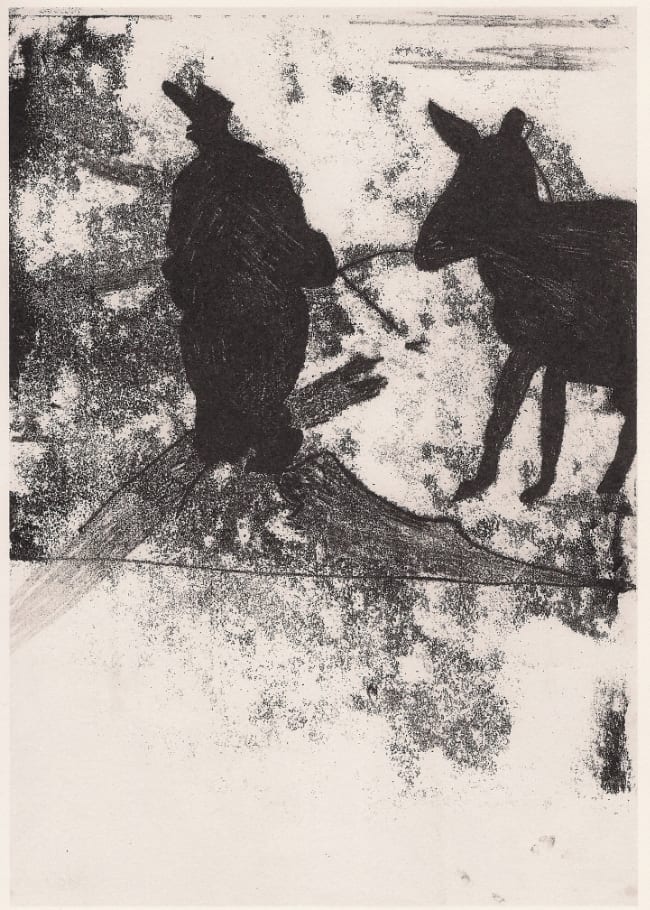

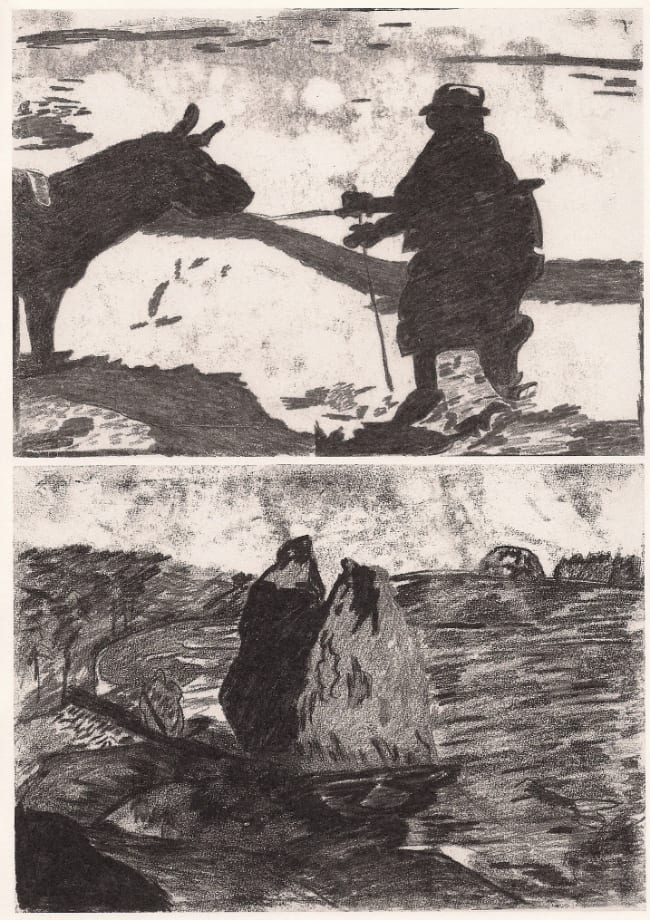

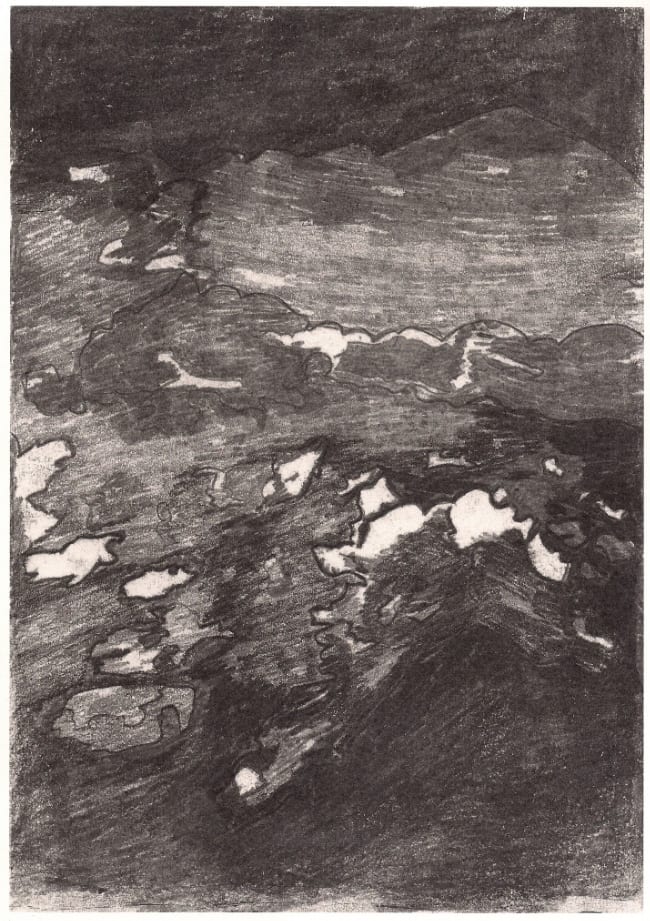

This is appropriate. Pierlot's subject matter is not only literature, but the cinema, with Orson Welles' unfinished Don Quixote sitting at its center. The book's text -- always occupying discreet panels, like silent movie intertitles -- looks to come from Welles' work, and that film's incomplete state is analogized through the artist and his crew's largely plotless succession of images, never more than two panels per page, forming acute juxtapositions often drawn from other movies concerned with illusion, deception and time: Le Mépris; La Jetée; Vertigo. If memory serves, the cliffs seen just above were shot by Godard, who cast Fritz Lang as a director facing difficulty in adapting a classic work; the POV then shifts to thin Francisco Reiguera staring up from a similar, real film, genuinely troubled, Welles tilting at windmills.

Pierlot positions Don Quixote as a time-traveler, wandering in and out of fiction and reality; Frémok, on its slipcase, declares the effort "an investigation of which you are the actor and the object, the client and the subject," bluntly asking whether the artist or the reader is best represented by the knight errant. After all, isn't it you looking at images in sequence, and imaging unreal connections between them? Is this search for coherency among eight lightly thematic packages a parodic mission?

Nonetheless, there is some intensity in these arrangements, communicating resilience, yes, but also menace, as the reader/hero's lucidity dissolves into nature and ink.

--

Two Toms (Dos Aldos)

By Pablo Guerra & Henry Díaz

El Globoscopio, $5.00, 40 pages

But I did not have to venture far to encounter comics of the type more typically associated with "Eurocomics" in the contemporary discussion - SF-flavored genre works fit for Heavy Metal, albeit not necessarily from Europe. Circling the far right side of the room, trying to get my bearings prior to the first panel I'd wanted to attend, I noticed a minimally-appointed table: very rare for the information-dense convention floor. The exhibitor was one Pablo Guerra, a Colombian artist present on behalf of El Globoscopio, a Bogotá-based collective; among his books was an exclusive print-format English translation for part of a webcomic he'd been doing with an artist, Henry Díaz. I don't know if the print sampler is otherwise available, although the serial is to be printed again when it's completed, some time in 2015.

I don't have very much to say about the plot of Two Toms; a woman, quite drunk and waiting for her lover to return home from some futuristic mission, inadvertently shags an unwitting alien, which -- through biological process -- had taken on the boyfriend's form. Complications ensue, pressing the now-pregnant woman, her possible-alive boyfriend and the depressive, unused-to-human-emotion alien into an uneasy cohabitation, though Guerra has a habit of moving the story's timeline quite a ways up between chapters, perhaps to inspire a mysterious curiosity, but also creating a somewhat confusing set of character dynamics for what does seem to be primarily a relationship-driven serial.

Nonetheless -- and I am, of course, cognizant that these are early chapters -- my attention was held by Díaz, whose characters generally engage in an unusual amount of gestural, almost stagey 'acting,' though really pours emotion into his depiction of the woman. Stretching her body into graffiti-like smooth contours, the artist lavishes his heroine with all manner of physical business: scratches, twitches - she doesn't so much as curl a toe without your knowing, communicating a sort of infatuation appropriate to the scenario. We see her, perhaps, as the alien might - from quarantine, observant and isolated.

***

12:30 PM: White Flint Auditorium, "Sex, Humor and the Grotesque" - Eleanor Davis, Julia Gfrörer, Meghan Turbitt, Katie Skelly (moderator)

There is a sharp differentiation between the two rooms available for SPX programming. In the larger room, the White Oak Room, panelists sit on a raised stage slightly above the audience. In the White Flint Auditorium, however, the audience looms over the panel, lecture hall-style. I don't know which I prefer while on a panel, as I am generally scanning the room for emergency exits, but when merely attending panels it's White Flint all the way for me, as I can sit way up in the back and pretend I am God, taking perfect notes. The room was nearly full, with Programs Coordinator Bill Kartalopoulos patrolling the aisles, pointing lost attendees toward empty seats.

Katie Skelly ran this panel as a medley of small interviews, spending roughly the first third directing groups of questions specifically to each of the three panelists, one after another, then asking group questions for the second third, and leaving the remainder to audience queries. She was way, way more organized than I have ever been, and made nice use of illustrative slides; she was practiced. As a result, I was able to arrive at my own impressions from this discussion of very subjective content prone to evoking specific, physical reactions.

I tend to see fictive violence, for example, in terms of spectacle and metaphor - to be grossly reductive, it's all the wounds of Christ for me, indicative of the idea of suffering. Naturally, then, I enjoyed Julia Gfrörer's description of the story of Salome over a gigantic drawing of the title dancer clutching the gore-pouring head of St. John the Baptist, "MISANDRY" splashed across the image; the Wildean variant of this tale had proven interesting to her, though I thought quickly of her Palm Ash, which struck me as story of Christian martyrdom which functions as both arguably a perspective on the insanity of the situation, as well a straightforward devotational - lines blur when you're dealing with saints.

Likewise, Eleanor Davis noted that her own use of grotesque violence is often to externalize emotional states; she mentioned exposure to Tove Jansson's Moomin works as a child, although she never clicked with the sadder stories until she was grown. Skelly made note of the tendency for Davis' works to mention "good strong bodies," which echoed an earlier suggestion that Meghan Turbitt's art creates -- despite its humorous approach -- a nightmarish sensation through its heavily overlapping images, spilling out from story panels; bodies in flux. One particular set of slides depicted several pages from Turbitt's #foodporn, in which an ugly pizza man transforms into a hunk in successive panels while Turbitt watches him make a pizza; this is cartooning, but also the subjectivity of desire, the activity culminating in the man seizing Turbitt and feeding her a slice in what could be pain or ecstasy, both of which tend to look similar, as Turbitt observed. But then, as Gfrörer mentioned, speaking for herself, there is little challenge to work that boils down to 'sex is good.'

There was something else that united the panelists. Among audience questions as to comic book influences and what you'd do if you couldn't make comics, one guy asked about 'shredding' reality in the creation of stories. Rapidly, all of the participating artists noted that their work was fundamentally autobiographical, whether explicitly so (as with Turbitt) or communicated through allegorical means. I took this moreover to mean that there was little in the way of engineering 'concept' with these artists, as you often see in popular comics - all is as personal as the twinges and rush you feel from sex, humor and the grotesque.

***

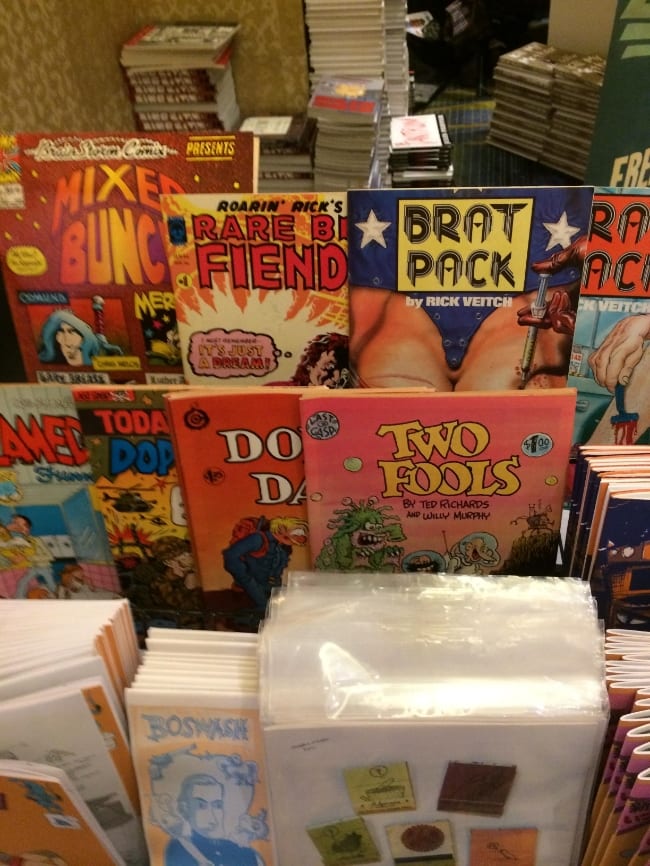

RAV 1st Collection

By Mickey Zachilli

Youth in Decline, $20.00, 276 pages

My thoughts remained grotesque all the way back up to the show floor, and that's what drove me to Ryan Sands. He's been participating in book creation for a while now -- he was co-editor/publisher of the erotic anthology series Thickness, and his Youth in Decline has been releasing issues of the artist spotlight series Frontier since '13 -- but I met him through the guro manga-cum-weird humor scanlation blog Same Hat!, which he started up with Evan Hayden back in '05; the two of them worked on Last Gasp's release of gross-out godhead Suehiro Maruo's The Strange Tale of Panorama Island from last year, which struck me as something akin to the end of the Same Hat! era - Maruo, truth be told, while still a master, had calmed down a lot since his oil slick bloodbath heyday, and Sands had other things on his plate.

So imagine my pleasure upon spotting this: the first 'official' bookshelf-ready Youth in Decline publication, and maybe the most holistically manga-informed American thing with a bar code at the entire show. I loved this book. It's like a very deluxe variant on a Japanese shōjo or josei comics magazine, 5" x 8" and printed on this heavy-ish yellow paper that arcs in intensity with your progress through the book, so that it's light at the beginning and end while dark toward the middle. There's brief, oblique supplementary texts, an omake puzzle section, and even tribute art by special guests - it's the total package.

What's all the more impressive is that I'd never really thought of Mickey Zachilli in that way at all.

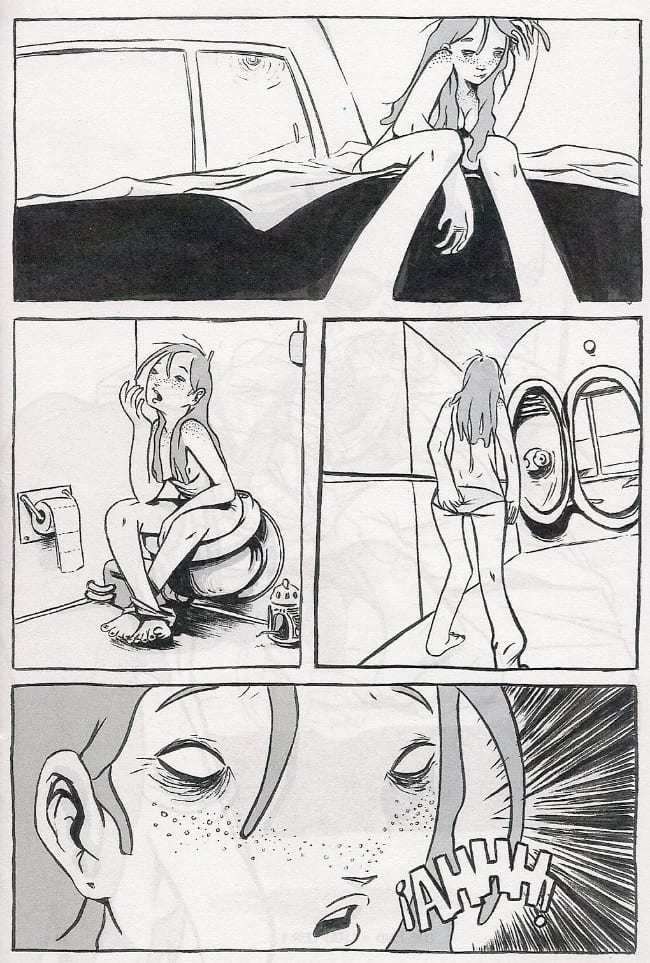

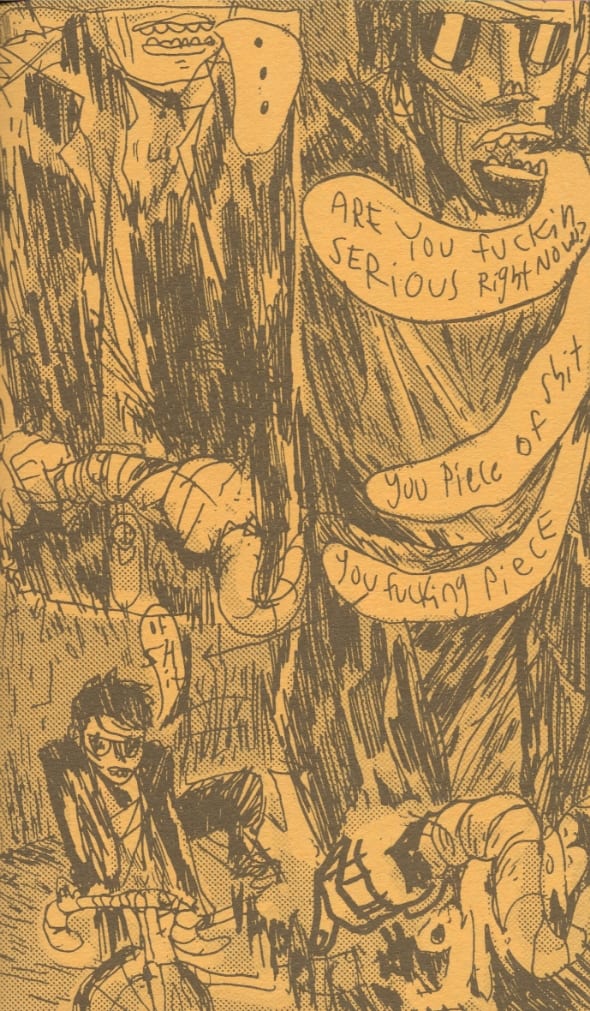

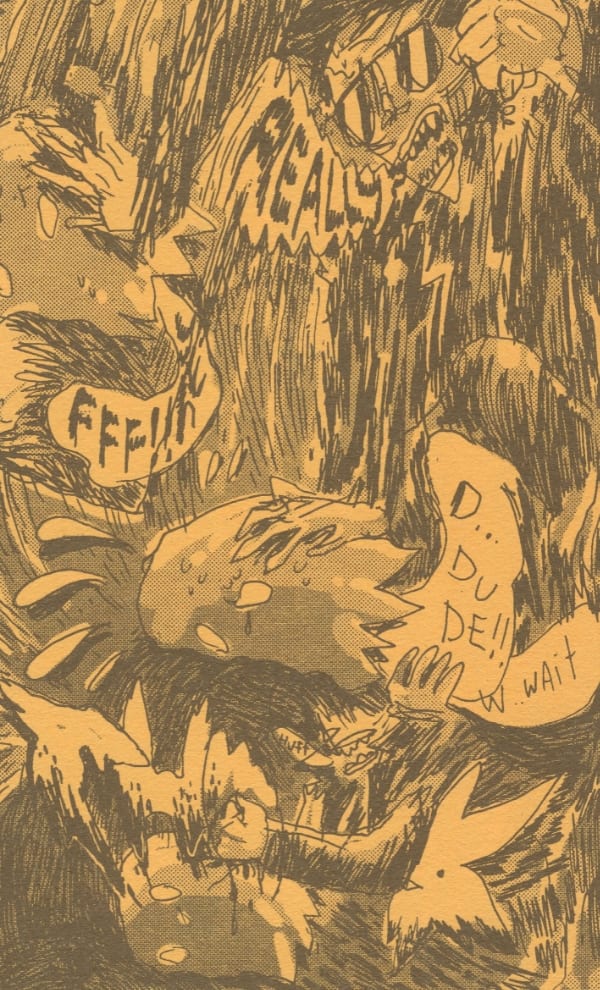

I mean, part of the problem is that I'm ignorant - Zachilli has explicitly attested to being "heavily influenced by manga," and it's not enormously difficult to spot elements of superdeformed exaggeration in the above page (the eyes in panel 2 have it). But I was always more inclined to see the 'noise' element of her pages - the heavy accumulation of visual data, pictures bumping into one another, words spilling out of balloons, and especially the sense of motion to her work: check out how those pushy bros bump into the story, crashing in from the left as your eye hits the rightmost panel of tier 1, then squishing in from the right as you cross down from tier 2 to 3, following, in effect, the invisible trajectory of the second guy's body.

I'm not going to be the first person to compare Zachilli to Brian Chippendale (who's among those paying homage in the back), but it's this sense of *motion* that coaxes me into associating her, psychologically, with the Fort Thunder experiments of Chippendale and Mat Brinkman. It helps too that RAV -- the title is to be taken as a wall-sprayed tag, with no particular bearing on anything in the story, yet -- has until now been presented in photocopied or risographed comic book form, its most recent issues tipping the scales at around or over 100 hand-assembled pages each. And most of the 'action' consists of characters conversing with one another, hanging around and falling in and out of relationships, flaunting a few mystic powers and encountering the occasional giant monster, but mostly just walking around and living.

Which - I don't think I need to tell you that kind of fantastical, romance-driven slice-of-life plot is also quite common to manga, or that Zachilli's visual style, while surface-loud, is both extremely fast-reading and VERY intuitive, with an almost unerring tendency to drop those pregnant little word balloons exactly where your eye is set to fall on the page; fundamentally, it's just the sort of thing that a manga magazine of the alt-flavored-yet-still-mainstream IKKI or Morning Two sort would look for in chasing something cool. Certainly the specifics of the story -- in which leather jacket-wearing cool guy Juice and delightfully sour magic lady Sally break up, meet new people, and generally swirl around each other's life trajectories -- are more focused and 'traditional' than something like Powr Mastrs, though Zachilli is not above simply hand-waving her characters into new situations via narrative captions like "also happening somewhere, somehow." There's even a few classically decompressed fights:

So, what we've got here is not just a collection of five early issues -- specifically #2-6, with #1 having apparently joined Lose #1 and Floyd Farland, Citizen of the Future in the Disney vault -- but a package that may transform your very perspective on the work, provided you are as soft-headed and context over-sensitive as myself. For the rest of you, I'd just like to add that issue #6 has the best depiction of a woman's orgasm I have ever seen in any comic, anywhere. This is the best thing I got at the show. READ IT.

***

1:30 PM: The Grand Ballroom-cum-show floor sectors "D" through "H" (approx.) (ref)

And so it happened that gradually -- hours after I'd arrived! -- I began my first real circle of the show floor. It was crowded, but always navigable; the aisles are pretty generous at SPX, and the organizers know enough to position the big tables and their inevitably major, show-stopping guests by portals to the foyer, so that everyone isn't milling around in front of other exhibitors' tables. As a result, funnily enough, I wound up not noticing the size of any individual artist's line, since I didn't have time to remove myself from the show floor and go stand in one.

I also decided I wouldn't ask anyone about any potential Book(s) of the Show; as Rob Clough would later note in his own, vastly more disciplined SPX report, the show has accrued numerous overlapping generations of attendees and exhibitors, enough so that the writing on the palimpsest is less explicit narration than a set of options to decode. SPX is not a wholly curated show, such as CAB, and thus lacks so explicit an aesthetic point of view, but it has a sense of history and purpose I find lacking in MoCCA or smaller cons - traveling to this isolated place, with everyone more or less trapped in a single location, is like witnessing something near the terrifying scope of the total comics conversation occurring at once, and all that's certain about that is agreeing upon some monocultural fave is increasingly unlikely. Hell, among my pallid thirty-to-fortysomething white boy crowd the hot ticket was Coach House Books' 2013 edition of Martin Vaughn-James's '70s Canadian graphic novel masterpiece The Cage - which, admittedly, is better than quite a lot of things, but isn't new by any definition whatsoever.

Walking around the room I saw children's comics, I saw pornography (presented with tact)... ratty old superhero back-issues and new 'mainstream' alternative stuff from Oni and the like. I saw autobiographical comics and cheapjack genre stuff, printouts of webcomics and white sheets of photocopied paper, folded over. Silkscreened covers were still a thing. American, European, Australian stuff. At one point a guy by the name of AJ Maguire walked up and handed me a copy of a critical zine he'd made with a few artists, Succour Fanzine, which started out awesomely with reportage from last year's SPX... why didn't I think of that?! Then there was a little piece about wanting to write something incisive about The Walking Dead but not wanting to go searching through dozens of awful comics for the images necessary to correctly illustrate your point - truly a publication after my own heart! I resolved immediately to be as concise as possible with my show report.

***

Two Eyes of the Beautiful Part II

By Ryan Cecil Smith

self-published, $8.00, 52 pages

Then, as if to puncture my delusions of addressing the sweep of comics in all its diversity, I encountered Ryan Cecil Smith and it was right back to manga for me. I think this series is where a number of people first discovered Smith's work, back in '11 when it was released in minicomic form. Two Eyes of the Beautiful is still self-published, but both issues are newly available as 6.5" x 9.5" comic books. I'm going to focus on the second issue, as Smith was extremely proud of the shiny gold-spotted covers, risographed in Japan for blue guts prepared in the U.S.

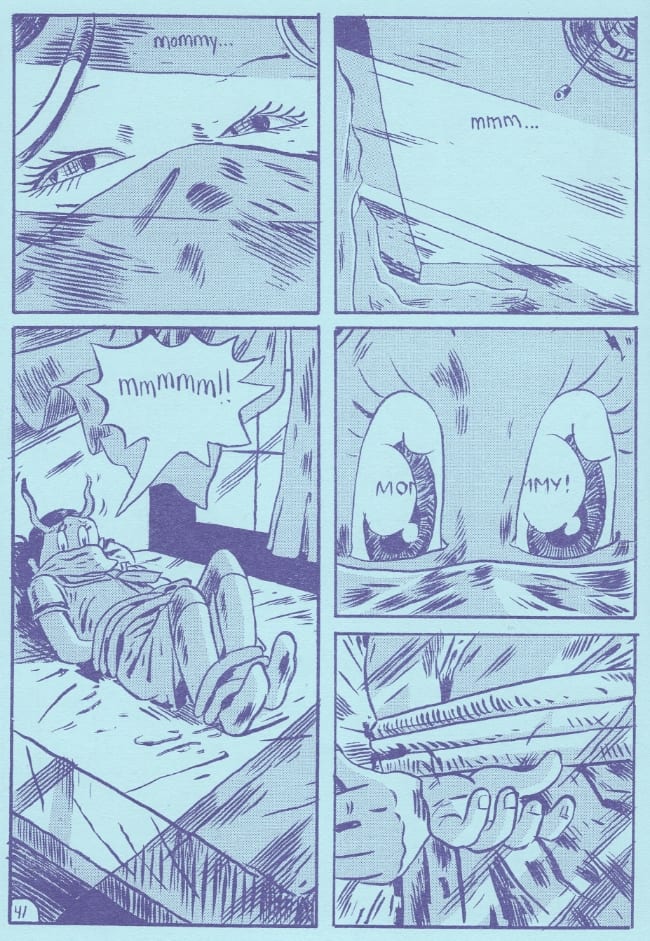

If we were in Japan, I'd be tempted to call these books dōjinshi, which really just means they're self-published, but carries an added connotation of using preexisting works and characters in an unauthorized manner. What Smith is doing here is creating a wildly compressed variant on the 1974-76 girls' comics horror series Senrei (or "Baptism") by Kazuo Umezu, that manic, completely idiosyncratic creator of The Drifting Classroom and other furied projects. I haven't seen very much of Senrei, which has never been printed in English -- some will be more familiar with a low-budget 1996 movie version, Baptism of Blood, readily available subtitled on dvd -- but I do know the first chapter culminates with a disfigured old lady straight-up beating the shit out of a preadolescent girl, so we can safely assume that Umezu's usual concern with the adult world's toxic influence on childhood development is in full effect.

Nobody is quite like Umezu, even artists like Junji Itō who follow closely in his footsteps, and Smith is no exception: his often wildly exaggerated cartoon forms are limber and exaggeration-prone in ways foreign to Umezu, who adopts a particular blend of heavy-detail backgrounds and doll-like child characters, their torsos tilting downward as they run, mouths flying open and eyes shining black. The most Umezu-like drawings of Smith's grace the inside covers and facing pages:

Still, drawing like Umezu isn't the point. Neither, frankly, is parody or camping it up, since Umezu's whole approach to horror already accounts for the thin boundary between comedy and terror in its gleefully over-the-top tone. No, what Smith does is open Umezu up to different ways of depicting scenes, like slipping word balloons outside the frame or behind characters' eyes, or switching back and forth between the story's degenerating actress villain and an absurdly flattering old movie of hers on television in harsh six-panel grids. I imagine there's a lot going on in the 1,000+ pages Umezu and his studio use for their story; in compressing it, Smith hones in hard on the conformist standards that drive women to hurt themselves and each other, if not always to the extent of having a daughter and instructing her on superior grooming techniques so that one day you can literally switch your brain with hers for the ultimate in vicarious youth. An all-new Part III is due at some point in the future, but it works pretty well here as the commentary it's bound to be anyway.

--

Daddy

By Josh Simmons & James Romberger

Oily Comics, $2.00, 12 pages

Horror of a quicker and nastier sort was waiting at the Oily table; this was their premier debut, which I came to see as an inadvertent tie-in to writer Josh Simmons' Eisner-nominated story "Seaside Home" from an earlier Oily release, 2013's Habit #1. You'll remember that little romp as a brutal collision between domestic horrors and the eruptive, gory stuff that represents the havoc on their victims, a reality-metaphor demonstration of cause and effect. This is basically more of that, as an irresponsible dad fucks around with his wife and -- almost exactly at the halfway mark -- allows Trouble to cross the threshold into the family home. The big difference is the presence of artist James Romberger, who adds a touch of classic horror comics flavor with big, chunky sound effects and some eerie rain-slick shadow play. Good shit.

--

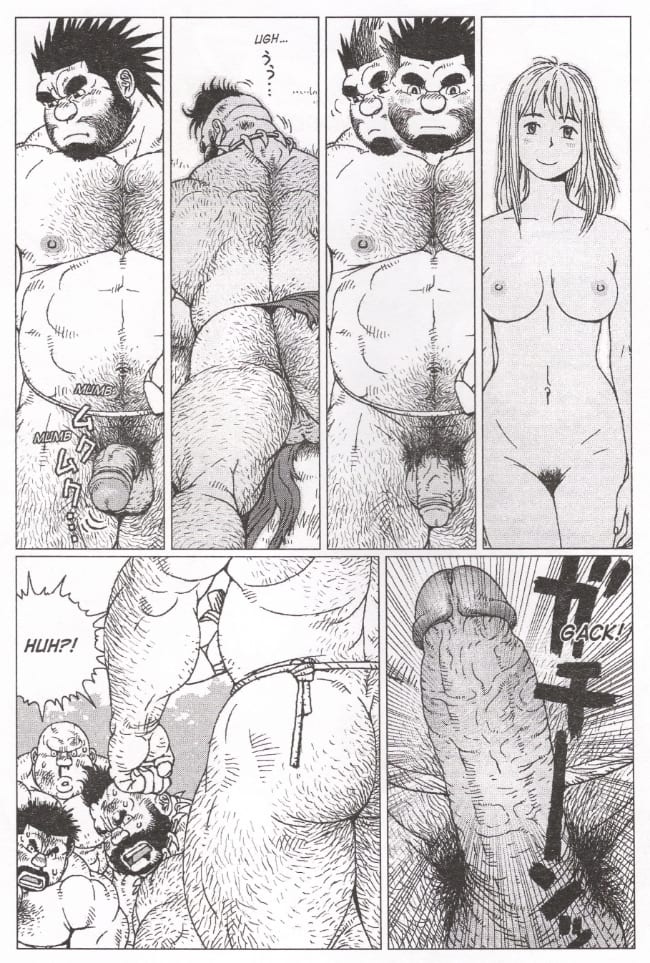

Caveman Guu

By Jiraiya

MASSIVE Books, $16.00, 16 pages

By this point I'd made it to the end of sector "D" of the ballroom, which is to say I'd gotten through roughly 3/5ths of the show floor before finally doing what I've always done at these things: somehow find the actual goddamned manga. There is always at least a little actual goddamned manga floating around, and -- notwithstanding the presence of longtime show guest Fanfare/Ponent Mon, which has just wrapped its translation of Jirō Taniguchi's Summit of the Gods -- the hot spot this year was an exhibitor which I think was technically there as a temporary guest of the aforementioned Coach House: MASSIVE Books, specialists in importation of manga by and for homosexual men and lots of related merchandise, most of it flaunting the ceramic-smooth musculature of bara artist "Jiraiya." Or - if you've seen basically any alt-comics show reports from the last year, you've probably seen people walking around in some very brash sweatshirts: that's MASSIVE, and that's Jiraiya.

In fact, there's so much MASSIVE stuff around I've gotten into the habit of forgetting that the actual book this all ostensibly supports -- Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make It, a sequel to last year's highly visible The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame -- hasn't been released yet, nor is it due until around the end of the year. I was glad for the sake of my sanity to clear this up, and doubly glad to meet Anne Ishii, the book's translator, and Christopher Butcher of TCAF and The Beguiling, whom I've known online for nine years without having actually met in person; Ishii commemorated this great occasion with a few glamor shots, highlighting my impeccable nerd posture.

This comic, as Butcher explained, is a brand-new work by Jiraiya, commissioned especially for the Massive book (and still set to appear in there), but showcased here separately with a signed bookplate as a means of... I dunno, delighting the west. Contra the spackled dudes of his illustration jobs, Jiraiya now works in a much lighter style, with lots of snub-nosed cartoon men fit for an '80s sports manga. It is, of course, hardcore pornography, set at the dawn of humankind, where the titular Caveman (*ahem*) Guu discovers that he's been totally mistaken on his assumption that fucking a lot of guys would help propagate the species. Seeking a damsel in distress to rescue and impregnate ("You're strong and big and smell good. I want to have your babies," declares a nudie cavegirl, problematically), Guu nonetheless finds himself compelled to fuck the brutes he'd otherwise fight off for breeding rights, thus revealing the true desires of numerous men and confirming homosexuality as an enduring human tradition. Basically a big goof on the idea of sex as a reproductive necessity, climaxing on several dubious consent scenarios, exactly tongue-in-cheek enough to qualify as ribald rather than horrible.

Then Chris Mautner tapped me on the shoulder. I hadn't seen him since before noon. "I've gotta watch the clock," I said, "I need to be at another panel."

"The Closed Caption panel?" he asked. "That started twenty minutes ago."

I immediately abandoned Chris again, leaving him to do god knows what.

***

3:00 PM: White Flint Auditorium, "The Closed Caption Comics Legacy" - Ryan Cecil Smith, Molly Colleen O’Connell, Noel Freibert, Conor Stechschulte, Brian Nicholson (moderator)

Oops. Well, from the twenty-five minutes I actually saw, this seemed like a good panel! I'd wanted to go because the Closed Caption Comics group was probably the first big art comics collective I discovered mainly through attending comic book shows, so I tend to associate them all with the unique quality of attending a show like SPX and using it to become acclimated to what's going on outside of the bubble you inevitably build for yourself in your daily stumbling.

There was a strong sense of community among the participants. The moderator was Brian Nicholson, another writer I've known online for the better part of a decade, and while I can't comment on his handling of the panel for its first half, he seemed inclined to push out questions (or sometimes just ideas) and let the panelists hold their own conversation, prompting each other with follow-ups of their own. Everybody clearly knew each other closely, which was evident from both the texture of their interactions and the content. They became friends in college due to shared interests: Mat Brinkman, Ron Regé, Jr. They became each other's "hype girls," as Molly Colleen O’Connell put it, offering each other intense enough support to carry them over periods of disenchantment and disinterest in comics. When Conor Stechschulte edited an erotic anthology, Sock, no small pleasure came from discovering that everyone else was kind of weird too - commonality in peccadilloes, which is a decent description for small press comics.

There was a prom after the Ignatz awards, you know. I didn't go; I didn't plan to. I didn't come here to fucking dance. Indeed, I had groused about the Team Comics of it all to Chris before we'd gotten there, and he'd cautioned me that cartooning is an isolated and difficult task, and that there was value in community-building - to let people working in a still-marginalized, labor-intensive field that they needn't be locked in a room forever. That there are horizons, and that yes, you do have to keep your eyes open -- another cartoonist told me later on that what the scene really needs is people willing to say "I like this person, but I don't like their work" -- but at the same time it does good to understand that other people understand. To face that. To feel that.

I walked out of the auditorium, alone, at panel's end, and watched the people spill out together. Brian Nicholson motioned to me. "I want to talk to you about Mad Bull 34!" he shouted.

"Maybe," I thought, "I can just review a lot of comics, and then nobody will notice my shitty reporting and nonstop solipsism. Yeah. YEAH!"

***

Lose #6

By Michael DeForge

Koyama Press, $8.00, 52 pages

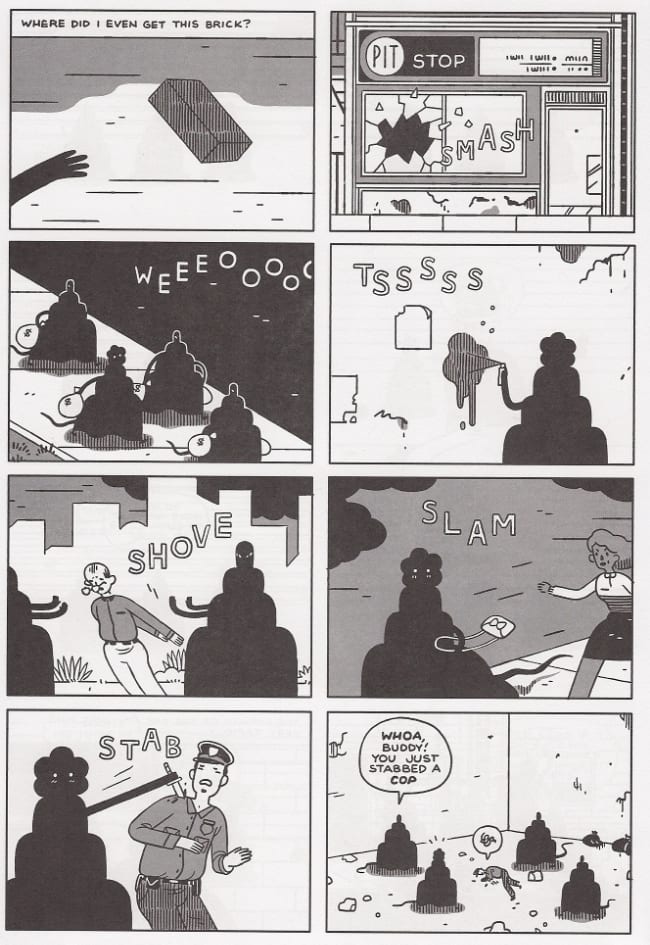

I've been joking that the release of Kill My Mother represents Jules Feiffer witnessing the revitalization of crime comics as a reliable genre and deciding to throw his hat in the ring, as if he's a massive Ed Brubaker fan - from what I've heard of Bill Kartalopoulos' Feiffer spotlight panel they only managed to get up to 1973 before the Root Hog or Die screening had to start, so he probably didn't make the admission there. Similarly, I don't know what Michael DeForge is reading these days, but I'll be damned if this isn't the "Here's to Crime" issue of his ongoing comic book anthology series, undoubtedly the closest new thing we've got to the likes of Eightball or Schizo right now in terms of popularity and sustained quality.

And know this - I am not idly making these comparisons. DeForge may be one of those cartoonists tasked with the burden of representing his generation to olds and outsiders, but I've always detected a strong kinship between his works and those of the ferociously self-recriminating authors of the '90s. Take this back cover gag:

Bang-on Chris Ware, that - or maybe Dan Clowes circa Ice Haven and beyond. Anyway, what I'm getting at is that I think the glamor surrounding DeForge tends to get in the way of evaluating what he's often trying to with his longer Lose stories in literary terms, i.e. explore intensely burdensome feelings of malaise by suggesting the presence of a parallel, counter-factual 'world' that teases out the otherwise suppressed or disguised nature of his primary characters. This tendency is present in Lose #1, which saw some very Ivan Brunetti-like despression comedy segue into a journey through comics iconography (at this early point 'comics' itself is the counter-factual world), and continues to develop through the insectoid coming-of-age in #2 and the bad behavior dog society of #3 (and its concluding dream of true animal nature), maturing into the leathery evolutions of #4 and the psychedelic zoo secrets of #5.

What we see in #6 is possibly the most 'real world' of these variations. "Me as a Baby" finds its protagonist in Cher, a professional woman whose dissatisfaction manifests in fantasies of pummeling her gormless husband's face, and a seemingly passionless affair with a married coworker she can barely stand. She's also cool toward her sister, Lena, who refuses to so much as approach the door when Cher picks up little Sally, her niece and Lena's daughter, for a big clarinet rehearsal. Intent on proving herself "a 'cool' aunt" -- and convinced that Lena is suffocating the child's self-expression -- Cher takes the kid to a hip store in a bad part of town, only for the girl's instrument and sheet music to be snatched from her hands by a man in black.

This is the counter-factual world, that of the Mafia, which DeForge depicts playfully as a secret club with onerous membership requirements. Naturally, Cher decides to visit all the bad old haunts of her youth (when she presumably felt cooler), and eventually infiltrates the Mafia itself, rationalizing her total and obvious enthusiasm for increasingly ugly activity as mounting the barricades for empowerment of her niece.

"She's going to grow up to be cool, I can tell," Cher muses, the text staid but her desperate eyes filling with tears as she beholds this avatar of all the hopes she used to have for herself. The girl is not a person to her, but an ideal, one she uses to distract herself from her own bad behavior - and her capacity for such is demonstrated in the Mafia world, which DeForge deviously pits against some recognizable personality types from today's social conversation. Take Cher's lover - a man with "stupid sissy 'nice guy' looks," the quoted bit implicating a very specific sort of man, who fancies himself a considerate friend of women while turning everything into a referendum on the awesomeness of himself. "Sorry if I was being a bitch at work yesterday," Cher later tells him, as a means of luring him in to a dangerous situation, promising sex as a rightful reward for his consideration.

Yet Cher actually *is* eventually a unarguably awful person, while her lover -- though simpering and blinkered to his privilege -- doesn't really deserve what he eventually gets. This heroine, circumstances suggest, is not unlike the 'nice guy,' in that the affections of such a dumb, shitty, cliché chump reflect poorly on the kickass goddess she fancies herself to secretly be. That Cher is evidently a black or brown woman adds an added racial dynamic to this story of crime and cool and authenticity, one I confess I don't feel qualified to address, though I can say I detect an almost LaButian perspective on vanished self-awareness and interpersonal cruelty - that all of this is conveyed in a squat style fit to collapse distinctions between realism and imagination is DeForge's signature, but we mustn't confuse the signature for the missive entire.

***

3:30 PM: The Grand Ballroom (misc.)/a crowded, on-premises Starbucks/I think it's fair to call it a terrace/the Grand Ballroom (reprise)

As this point in the day I was exhausted and starving, wandering the floor almost at random and striking up minute-or-less conversations with people I recognized. From what I could gather, the crowd thinned a bit at the middle of the day, and then bulked back up in the late hours. Chris and I got some food at the Marriott Starbucks -- the line for which stretched all the way back into the seating area behind, though I can't think of any way this situation could be avoided, there's just not much around in Bethesda without putting down some serious walking time or getting in a car -- and went out to eat on a terrace. The sun had begun to come out. I couldn't tell who was an attendee and who was a truant exhibitor. I *could* tell which one was an SPX worker, as he was off in a hidey-hole alongside the bottom of the exterior staircases, chattering into his cell.

"You should put that in your con report," Chris remarked. Good idea. Just keep writing. Nobody's going to read this far. Keep writing, keep writing; if it's long enough people will call it epic say wow and retweet you and not actually read it, they'll just assume it's good if it's long enough, keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing keep writing

***

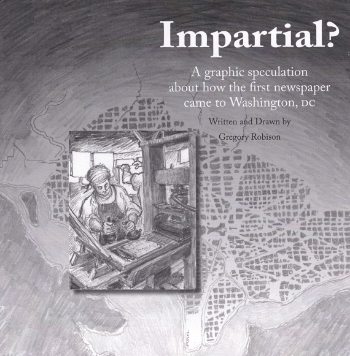

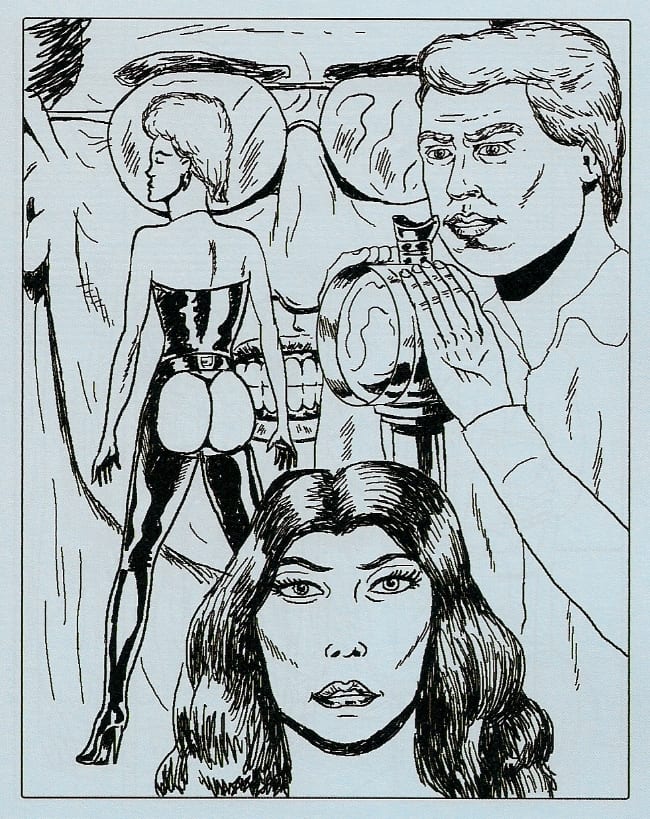

Impartial? A graphic speculation about how the first newspaper came to Washington, DC

By Gregory Robison

Peregrinus Press, $5.00, 16 pages

"Hey!" a voice called.

How did I get back on the show floor?

"Have you ever thought about how the first newspaper came to Washington, D.C.?"

I'd thought the man a cosplayer, given his straw hat and period dress, but he was an exhibitor. There were exactly two individual copies of this comic on his table; they were all he had left. The copyright date was 2011. The author/exhibitor was Gregory Robison, who appears to have no web presence in his cartooning capacity. He locked eyes with me and laid down the hardest motherfucking sell of the weekend. I gathered he was a Bethesda local, and he was selling a genuine local comic, albeit one that supposedly appeared again in District Comics, a Harvey-nominated anthology from 2012.

Here is the best panel from the comic:

I like all the scribbled foliage; not so much the lettering, which clashes badly with Robison's pencil images, but I don't think this is a comic that's shooting for a total aesthetic experience so much as a novel and pleasant means of telling its story, a bit of speculative history on the journey of publisher Thomas Wilson to Greenleaf's Point in 1794-95, where he encounters land speculator James Greenleaf and finds himself persuaded to set up a newspaper as a means of bolstering the man's investment; the Impartial Observer was a joke on the anti-Federalist Wilson's part, an illusion of unity as a means of broadcasting substance to an uncertain place.

Robison seemed delighted that I was from Pennsylvania, given its place in national history. I grinned. I was totally going to buy his comic. I grinned even wider when I realized that this man had talked me into getting a comic about one man getting talked into a business arrangement by another. Living history, this.

***

6:00 PM: White Oak Room, "Inkstuds Live" - Michael DeForge, Simon Hanselmann, Patrick Kyle, Robin McConnell (moderator), Brandon Graham (co-moderator)

We were nearing the end. The show would close at 7:00, and this was the last item of Saturday programming.

Robin McConnell would later refer to this special 'comics convention panel' edition of his audio interview show as "the super awkward hour" and a "train wreck" - it was a shambles, but an entertaining one, which frankly is the mode I aim for on all of my podcasts, so I'm in no position to criticize. Simon Hanselmann didn't actually show until about 15 minutes in, dropping a bag of books on the table with a crash and insisting he'd been Julia Robertsing around. Technically, the panel was meant as a tie-in to the Hanselmann/Michael DeForge/Patrick Kyle tour starting up, and it augured well for fraternization at future live events; there was a lot of superb ball-busting. Hanselmann, it should be emphasized, is extremely good at off-the-cuff witticisms, lobbing bon mots into the audience and toward his peers at a lively clip, and sometimes just proving sight gags, like holding up a microphone to Brandon Graham's face (Hanselmann took to calling him "Brandi") and then pressing it in harder and harder and harder.

There wasn't much organization to the questioning, with topics swirling often on their own accord from accounts of pizza in Oslo to which of DeForge and Kyle was the cuter boy. There was, however, a particularly interesting moment of contemplation. At one point an audience member asked the panel if any interactions with fans had caused them to alter their creative process, leading Graham -- who, since the Inkstuds tour Kickstarter, has functioned as the show's co-host -- to launch into a story about meeting a teenage girl at a show who excitedly told him she'd been teaching herself to draw women from his work. He was overcome with the desire to direct her toward Carla Speed McNeil, and verily realized that he had a responsibility to stop drawing women 'from just the neck down.'

Then it was back to fun. Hanselmann remarked that at least everyone was laughing - "usually when I listen to Inkstuds all I hear are crickets." He was then informed that it took a lot of effort to record all those cirps out in a marsh. I think I told that joke right. Honestly, I can't even read my fucking notes from this late in the day. What a disastrous reporter I've turned out to be. At least it was over.

Except...

***

Frédéric Magazine 4

Founded by Isabelle Boinot, Frédéric Fleury, Emmanuelle Pidoux, Frédéric Poincelet & Stéphane Prigent

Les Requins Marteaux, 25,50€, 288 pages

So here's what happened: there was ten minutes left. I made my way back to the show floor, one last time, and I found myself talking to Benjamin Marra. I noticed that among his own comics he had a copy of this, which I'd initially mistaken for a personal sketchbook, so dynamic was its cover. It was not; in fact, it was a zero-distraction presentation of the art of drawing, as curated by the long-lived website Frédéric Magazine in support of a 2011 exhibition at the Musée international des arts modestes. As far as I know, it is the final issue of the print-format Frédéric, which sought to emphasize the quality of drawing in the same way as more texty French magazines like Collection Revue. There is almost no text in here, though; it's just drawing after drawing after drawing after drawing, with only the order of contributors listed on the front cover to guide you.

"Is this for sale?"

"Yeah."

"There's this one guy over there," Marra said, pointing behind him, to the row closest to the wall. His name was Brad Gottschalk, and Marra and Tom Neely had been checking out his stuff. They didn't know of any other shows he exhibited at; he was apparently a self-taught cartoonist, making totally personal works that just seemed to spill out. Marra described his drawing style as "patient," which is not a word you hear often from critics, because they often do not do very much drawing.

There were three minutes left.

--

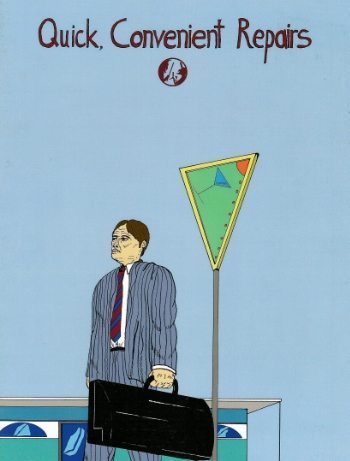

Quick, Convenient Repairs/Unfit for Human Company

By Brad Gottschalk

Silent Theater Comics, I don't remember, 28 pages

Nobody was seated at table A4, save for a young boy, maybe 9 or 10 years old. I thought about asking if he was Brad Gottschalk, but then I thought I should try conceiving a child before dropping too many dad jokes. There were four or five 8.5" x 11" comics on the table; some of them apparently used to be carried by John Porcellino's Spit and a Half distro, but I don't know if they are anymore.

"What's the newest one?" I asked, peering at the copyright dates.

"I dunno. My dad knows. He'll be back soon."

I picked up a flip book of two short stories. They're online, linked above, but I don't know if you can buy the paper copy anywhere. I don't even remember how much was charged, bringing a fitting close to this banner day for comics journalism.

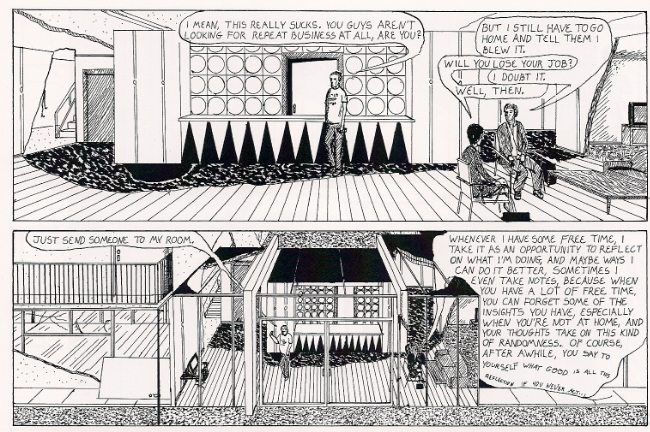

I will focus now on the story "Quick, Convenient Repairs".

From his website, I learned that Gottschalk had worked extensively in theater, and that his approach to comics "mainly been shaped by [his] theater experiences." Indeed, much of "Quick, Convenient Repairs" consists of dialogue between two characters at a time, or navigation of the large artificial space that is a strange hotel, to which a businessman has come for an enigmatic meeting. I can't vouch for the dialogue as superior music, but that will you lose your job/I doubt it bit is pretty real.

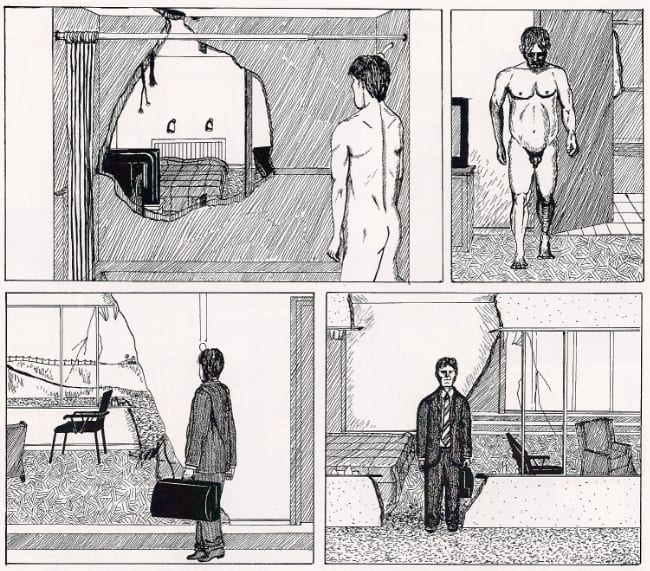

This comic *is* shooting for a total aesthetic experience. Here the point of view pulls back to gaze upon much of the entire 'set' - a typical enough flourish, but Gottschalk also toys with mimesis in depicting the hotel as blasted full of holes in the walls and ceilings, which only the businessman protagonist seems to acknowledge, as his life is ripped bare.

The purpose of his trip is to demonstrate a peculiar medical device for a potential client. Before that, he chats up various other tenants; all seem trapped and dissatisfied in this life. He fantasies about sex with a muscular cleaning woman, the borders on the panels of his dreams wavy and torn like the walls of the hotel/set. Gottschalk has problems with page design, of guiding the eye to where it's supposed to go - putting word balloons in an intuitive order, arranging panels in a manner so that the reader stays on the path. Fundamental, tough-to-master comics stuff. His imagination comes from stagecraft, I think, of in-panel properties. His drawing his pained.

The medical device, as you can see, stitches up cuts on its own, but leaves scars; every demonstration is more lost skin, and contributes -- perhaps -- to the feeling of dealing with a loser. It's like walking through the crowd at one of these comics shows and seeing the crowd thin around certain tables, and wondering if the absence of a crowd doesn't reinforce the sensation that quality is lacking there, ensuring that no subsequent crowd will gather. That's the kind of angst we're dealing with here, or really just an application of such angst. My application, his angst.

I was glad to encounter it.

Then a voice came on the loudspeaker and announced that the Small Press Expo was closed for the day.

There was scattered applause, and everyone left.