It was the Dr. Who of the 1940s, a comic strip that traveled though history with verve and panache -- not to mention lots of wisecracks. Only, instead of charming, eccentrically dressed Englishmen wielding sonic screwdrivers, there was a practically naked caveman with a stone ax. Begun in 1932 by Vincent Trout Hamlin (1900-1993), Alley Oop continues to this day, ably written and drawn by Jack and Carole Bender and appearing in about 600 newspapers.

Alley Oop is an iconic American newspaper comic strip character. His nipple-less, six-packed, Popeye-armed body is as memorable and weird as Dick Tracy's hooked nose and Little Orphan Annie's blank eyes. No history of 20th century American comics, no matter how slight, would be credible if it didn't include Alley Oop. Aside from that iconic status, why should anyone today care about the early years of this ancient, dusty comic strip?

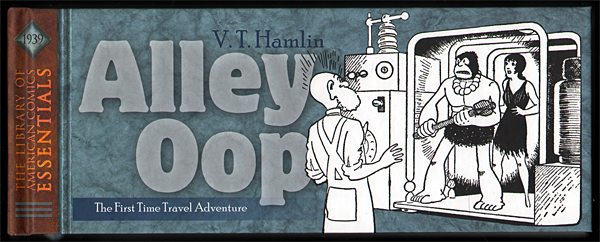

For me, a comics nut who was occasionally and momentarily drawn in by Hamlin’s singular visual language, but never fully “got”Alley Oop before, the answer lies in the strip's seventh year, a good chunk of which can now be found between the slate grey covers of Alley Oop 1939 (Dean Mullaney, editor, introduction by Michael H. Price, IDW Library of American Comics Essentials, 2013). This spiffy little volume presents, with the typical smart design and good production qualities we've come to associate with Dean Mullaney's Library of American Comics books, the daily episodes of the strip's first time travel adventure, from March 6, 1939 to March 23, 1940. You read that right: time travel.

This sequence of comic strips is, in my mind, a touchpoint of the school of clever and skillful meta-storytelling; a breakthrough example of a series growing, stretching, and turning itself inside out. When a popular science fiction series like, say, J.J. Abrams' television show Fringe (2008-2013) used an impressive-looking device to yank characters from one alternate universe to another (and even in a memorable episode, into a cartooned simulacrum of reality with Leonard Nimoy as tour guide) and played with its own storylines and structure in artful and clever ways, believe it or not, it was walking the same trail that Alley Oop helped blaze in 1939.

In early 1939, after seven years of penciling and inking the tens of thousands of crisply drawn rocks, trees, and pubic-hair-fuzzy loincloths that that constituted the prehistoric world of his popular daily comic strip, Vincent Trout Hamlin (who preferred to be called "V.T."), cartooned a time machine, pulled his anarchist-outsider caveman into the present (which in this case was 1939) and exploded his sharply defined fantasy with a precisely rendered blam.

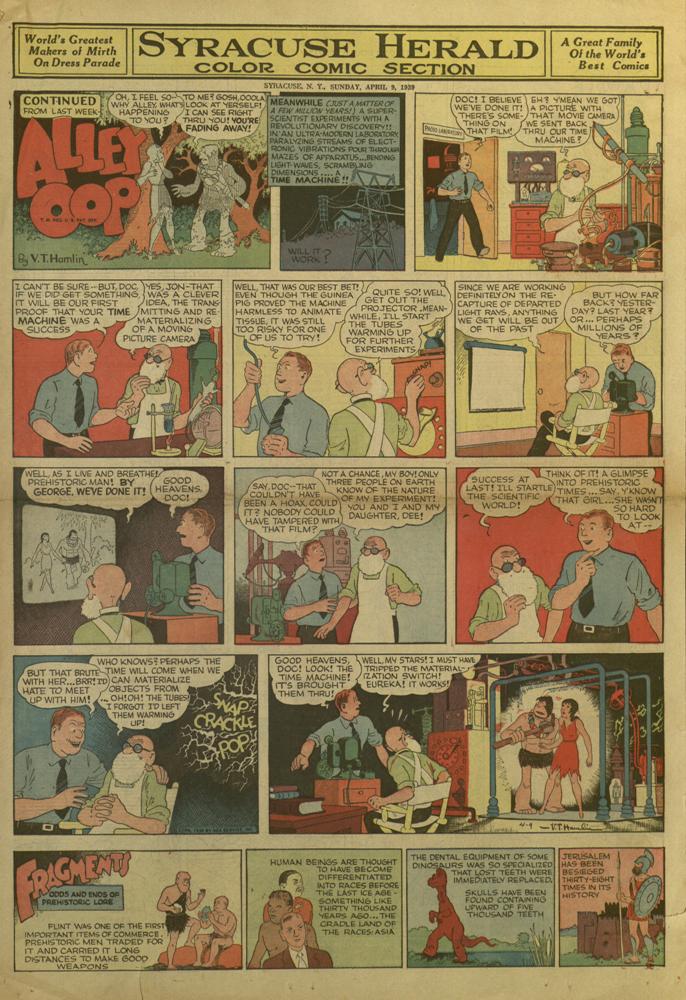

In 1939 and the years that followed, Hamlin wove into his daily humor fantasy increasingly ambitious stories about modernity, technological progress, social order, the cycles of history, gender politics, and ethics. And there were nutty scientists, wall-sized banks of delightfully complex electric dials and vacuum tubes, and a host of hugely entertaining historical personages. It could be argued that if Hamlin hadn't spent the previous years establishing the rock solid foundation of his cavepeople comic strip, the 1939 time travel maneuver wouldn't have worked as well. When Hamlin introduced time travel into his series, he effectively turned the previous seven years of strips into a very long first chapter to the time travel years.

Cartoon dinosaurs and the everyday lives of cavepeople were well established in American comics by the time Hamlin tackled them. Fossilized dinosaur bones were discovered in North America in the mid-1800s and became a national sensation. Illustrators and comic strip creators, always on the hunt for novel concepts, jumped on the dinosaur mania like a velociraptor on a fat, slow-moving businessman. For example, the enormously gifted and now virtually forgotten illustrator-cartoonist T.S. (Thomas Starling) Sullivant (1854-1926) drew, among his many subjects, ugly, near-naked cavepeople and elegant dinosaurs in his cartoons in the pages of Life and Judge for decades, starting in the 1890s.

Another artistic T.S., Thomas Stamps Allen (also a member of the First Initials Club), created an unnamed daily panel (sometimes referred to as Adam and Eve) about prehistoric cave-dwellers that started in 1898 and continued until 1902.

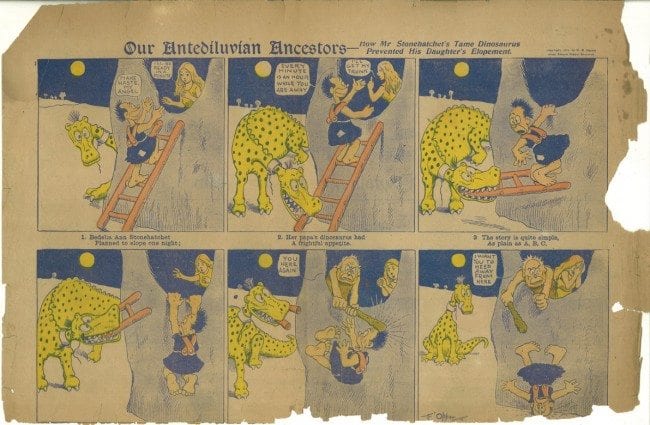

The accomplished illustrator who became an innovative sequential graphic gag-man and comics master Frederick Burr Opper, best known for his Happy Hooligan comic strip, created Our Antediluvian Ancestors (1900-1904) a weekday panel and a color Sunday topper in which anatomically dubious but nonetheless charming dinosaurs and primitive people engaged in Opper's patented screwball-slapstick chaos. A book collection was published in 1903, and Opper briefly revived his strip for a few months in 1926.

Most famously, Winsor McCay animated a dinosaur named Gertie in 1914, and more than once leveled New York City with lost, lonely, childish dinos in his comics.

In fact, the history of comics reveals a volcanic eruption of cavepeople and dinosaurs in the early 20th century. The subject is so rich that comics scholar, author, book designer, and publisher Ulrich Merkl (The Complete Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, 2007 -- a volume that is, sadly out of print and which at the time of this writing commands prices as high as a rare prehistoric fossil) has created a richly illustrated volume on the evolution of dinosaurs in comics and pop culture. The book is forthcoming from Fantagraphics and, Merkl tells me with tongue firmly in cheek, has the current mammoth-sized working title of Taxpayers Wouldn't Like This: Winsor McCay's Lost Dinosaur Strip, The Evolution of Dinomania, The Origins of the Giant Monster Movie, The Iconography of King Kong, and the Irresistible Urge to Destroy New York. Merkl's extravaganza includes further excavations of forgotten cavepeople comics, such as Jack Abbott's jaunty Gay Stone Age (1929), in which our antediluvian forebearers wore fetching animal skin vests, pants, bras, and shorts and were hep to the jive.

Prehistory, it seems, had quite a history by the time V.T. Hamlin created, and then torched his Oop the Mighty comics in 1930. These were his first works about cavepeople and dinosaurs (and, by the way, Hamlin was a student of history and well aware that humans came along after the dinosaurs died off), and a run-up to his next strip, Alley Oop, which he sold to the tiny Bonnett-Brown Syndicate in 1932 and then to the larger operation of NEA in 1933.

Generally, the idea with prehistoric comics was not to depict life as it actually might been in primitive societies (as some writers have done, including William Golding in his 1955 novel The Inheritors and Jean M. Auel in her celebrated Clan of the Cave Bear series of the 1980s), but rather to satirize contemporary times. Certain aspects of human nature, particularly the war between the sexes, seemed to be cast into sharp relief when played out by pen-and-ink caricatures of our primordial forbearers – the meta-gag being that some things never change. Plus, cartoons of dinosaurs, stone axes and half-naked people have a certain goofy charm, especially if the dinosaurs are bright yellow with black polka dots.

The early years of Alley Oop and his fellow Moovians are full of charm. Hamlin delivered a rollicking adventure comedy with art that just got better and better. He proved to be adept at character development. However, after seven years, Hamlin’s strip was in crisis: its author was running out of ideas. Comics artist Frank Stack (who worked in underground comix as Foolbert Sturgeon, drew some of Harvey Pekar's best stories, and was Professor of Art at Missouri University for forty years), an expert on V.T. Hamlin, has quoted Hamlin as saying that by 1939 he felt like he had “overgrazed the pasture.” In his thoroughly researched Hamlin chronology, “The Winding Path of V.T. Hamlin and Alley Oop” (published in Alley Oop: Mystery of the Sphinx, Kitchen Sink Press, 1991), Stack notes that as early as 1936, “Hamlin has trouble inventing fresh material for his Moovians.”

Hamlin, a bold risk-taker not unlike his famed comic strip character, saved himself by trying something fundamentally different, and this is where the story gets really interesting because the time travel idea was so much more than a story gimmick. The result of Hamlin’s experiment transformed him from a comic strip author who told stories and made drawings about more or less the exact same characters and place for years (admittedly with some cool cartoon dinosaurs) into a virtuoso visual storyteller tasked with rendering a vast parade of people, places, and times. Instead of caves and rocky precipices, Hamlin drew, with great detail (as his eyesight worsened), the gadget-strewn lab of Dr. Wonmug, the orderly streets and interiors of small town America, and the cities, boats and armor of the ancient Trojans. He went from rendering cartoonish dinosaurs to the Trojan horse. And he was just getting started. It must have felt like leaping out of a mud puddle and into the ocean.

The idea was simple: introduce a time machine into the strip and get Oop into new settings where he could interact with new characters. The concept came from Hamlin’s wife, Dorothy, who also lent a hand on the art chores (joining the society of uncredited wifely collaborators on great comics, the ranks of which include Carl Barks’ artist wife, Garé, who contributed elegant lettering to his duck comics). Hamlin was so struck by the idea that he went straight from his mother’s funeral in Florida to the syndicate offices in Cleveland to pitch it. It took a little convincing, but the new direction won a green light.

In the 1939 Sunday page strip published on April 9, Hamlin yanked his cocksure, wise-and-skull-cracking cave man into modern times (the America of 1939), and his readers into the start of one of the more interesting, accomplished sagas in twentieth century newspaper comics – Alley Oop’s time (and space) travel adventures. Readers of the strip must have been as dumbfounded as Bob Dylan fans were in 1969, when the official voice of their generation recorded Nashville Skyline, a country album in which he crooned a song that rhymed moon with spoon. In Hamlin's case, the abrupt shift proved to be a particularly brilliant strategy.

As the weeks and months of the new continuity unfolded in the newspapers of 1939, Hamlin bounced Oop back and forth from the present and the past, to the events of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. From that point on, all bets were off as to where the strip would go next. Hamlin, a restless and ambitious man who traveled all over the country looking for success in a dozen or more professions, including football player, boxer, reporter and movie actor (sadly, there are no films with Hamlin as he screen tested but failed to land any parts) before creating his popular comic strip, seemed to relish taking the strip into new historic time periods, all resplendent with new details to savor and new characters to develop.

Alley Oop 1939 collects the black-and-white daily strips, but not the full page color Sundays, which are also part of the continuity. However, the story flows just fine in the dailies collection. Because some newspapers only ran the dailies and others only ran the Sundays, Hamlin had to artfully build his continuities so that they made sense read apart as well as together.

The book, like all of the entries so far in the Library of American Comics Essentials series, is oddly shaped as a long rectangle; the shape of a comic strip. The daily comics are printed one to a page, “allowing us to have an experience similar to what newspaper buyers had many decades ago – reading the comics one day at a time,” as the back cover copy explains. And indeed, the act of turning the page does somehow resonate with the story’s original structure, an adventure told in few hundred serial pieces. It’s interesting to consider that the classic continuity comic strips of mid-20th century America embrace sequential art by telling a story from one panel to the next, and also through carefully constructed groups of these short sequences.

There’s something about Hamlin’s precise line (as clear in its own way as the famed lines of Hergé’s Tintin) and intelligent, design-oriented arrangement of visual and story elements that seems particularly well suited to the idea of a long story told in a sequence of smaller sequences. Reading the strips in this volume imparts a satisfying sense of structure, similar to walking through a well designed building.

His gradient cross-hatching, used sparingly throughout his strips to great effect, has the best of Hamlin’s technique – disciplined, logical, and filled with zest.

The compositions one finds in these strips are often dense and dramatic, with word balloons layered over the edges of narration boxes that are dovetailed into opening scenes that include newspaper front pages and skillful figure groupings. This is an approach that Will Eisner would soon adopt in his Spirit strip, which was just around the corner (and which sometimes played with time travel stories).

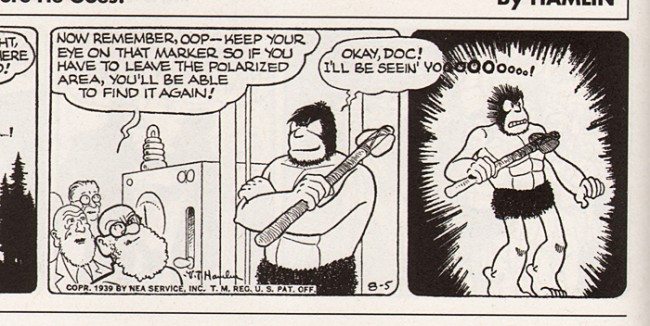

Even Hamlin’s lettering is packed with design. Sound effects are arranged to direct the eye through the narrative. In the August 5, 1939 strip, Hamlin uses Oop’s dialogue to propel us to the last panel, as he leaves the current day and starts a journey to the past, saying “Okay doc! I’ll be seeing yooooooooo!” The last word stretches across the gutter between panels three and four. We can see the boxes of a sequential graphic narrative as liner flashes of time – and therefore Oop’s “yooooooooo!” caused by his time travel in the story, is mirrored by a literal stretching across time represented graphically.

It must have been both a challenge and a joy for Hamlin to draw new settings. He appears to have taken on the challenge with the swagger and competency of his famed cave man. For a few weeks, as Oop wanders aimlessly around the present, causing comical chaos, Hamlin creates some impressive depictions of 1939 small town America. In one panel, from the June 5, 1939 strip, Hamlin draws a raised view of a four-point intersection with 17 people, three automobiles, a horse, and an overturned milk truck (it would seem that some towns in 1939 still received home milk deliveries from horse-drawn wagons).

Despite the radical shift in setting, Hamlin’s art never falters. His storytelling doesn’t weaken, either. Oop’s first days in 1939 offer some great moments, as when he confronts a speeding railroad train, which to him seems like another dinosaur. Oop reacts to the brutal force of human-made technology in a way that is similar to how William Faulkner describes a train hurtling through a forest as a living being in his story “The Bear.”

Oop is not the only time traveler from the prehistoric past. His girl, Ooola, comes with him. Hamlin then splits the narrative between Oop’s countryside and small town wanderings, and Ooola’s story as a strong, capable woman finding ardent admirers among 20th century American men. She dons fetching boots and jodhpurs and learns to shoot a gun with deadly accuracy. Ooola’s progress resonates with the story of gender equality in America, even as she exclaims, "But I'm not a modern girl!"

Perhaps inspired by his feminist theme (and as Michael H. Price’s awfully fine introductory essay informs us, it was Hamlin’s wife , Dorothy, that suggested introducing time travel into the strip – although it’s not noted that, in 1935, Harry J. Tuthill did a time travel feminist comedy story in his Bungle Family strip -- an adventure that is reprinted almost too small to read in Bill Blackbeard’s Comic Strip Century), Hamlin takes his narrative back into the past and collides with Helen of Troy, she of the face that launched a thousand ships.

Hamlin builds his sturdy narrative around the Trojan horse ploy, which is so vividly drawn that it made me wonder for the first time if the soldiers inside had to sit in their own pee and excrement as they hid inside the horse for days. It’s only a matter of time before Ooola and Helen erupt into a furious, erotic catfight.

As the weeks tick by, Hamlin weaves in multiple characters, from historical figures to brilliant-but-nutty mad scientists (Price’s essay in the book reveals that Dr. Wonmug’s name is a pun on Einstein, which translates as “one mug,” as in a beer stein, get it?).

The larger-than-life promise of the anti-hero, agent-of-chaos character of Alley Oop is fully realized in the time travel stories, which continued after 1939 and, as Michael H. Price informs us in his intro, toured “the Crusades, the Southern and Western frontiers of 19th-century America, and 18th-century sea piracy.” Hamlin also took Oop to ancient Egypt and the moon. You want interesting stories? Good old Vincent Trout had 'em.

When V.T. Hamlin took his caveman outsider figure and began jumping through time with him, he did it without any preamble. It was as jarring as it would have been if, after the first seven years of its existence, Peanuts morphed into a western. Against all odds, Hamlin's artful storytelling and convincing visual style made it seem congruent with what had come before, and even inevitable. For my money, the 1939 Alley Oop time travel shift is one of the more interesting moments in the history of American comics, and a darned good read, besides.