What's Mything by Bob and Adele Levin

woe to him who seeks to please rather than to appal... Delight is to him...who

against the gods and commadores of this earth, ever stands forth his own indomitable self.

From Father Mapple’s sermon in Moby Dick

Shortly after midnight on November 1, 2010, the sixty-nine-year-old cartoonist S. Clay Wilson was discovered lying unconscious between two parked cars on a San Francisco street in a pouring rain. Wilson had spent much of the previous day and evening drinking, but whether he had fallen and struck his head or had been assaulted was never determined. He had a broken neck and damage to his brain’s frontal lobe. Multiple surgeries saved his life, but he was hospitalized for a year. His short term memory was permanently damaged, and he was left dependent on twenty-four hour care.

Wilson had come to prominence as one of the underground cartoonists of the late 1960s, who transformed comic books into a medium where artists could express themselves without limitation. Among these boundary breakers, Wilson was the most destructive. Among these taboo defiers, he was the most unabashed. Sex’n’violence – always grotesque and always comic – was his metier.

He "liberated underground comix," his colleague Robert Williams said. He "blew the doors off the church," according to Victor Moscoso. Spain Rodriguez felt "pushed" by Wilson’s example to reach for "things that were on the edge of my consciousness." And Robert Crumb said Wilson possessed "a nightmare vision of hell on earth never so graphically illustrated in the history of art.... (After him) I no longer saw any reason to hold back my own deranged id."

Kathy Acker, William Burroughs, and Ken Kesey sought Wilson to illustrate books. Robert Hughes was a fan. Sir Kenneth Clark compared him to Hogarth. Museums displayed his work beside Hieronymous Bosch. If Giotto deserves acclaim for opening Renaissance art to naturalism and Edouard Manet the Paris Salon to modernism, Wilson deserves it for opening graphic art to... Everything.

Patrick Rosenkranz’s Pirates in the Heartland (Fantagraphics 2014), is the first of what-promises-to-be an info-filled, art-so-rich-its-choking, three-volume celebration: "The Mythology of S. Clay Wilson."

I

While "Pirates" is structured to track Wilson chronologically from his birth in Nebraska, through rip-roaring stops at its state university, New York’s Lower East Side, Lawrence, Kansas, into San Francisco, concluding in the late 1970s, with Rosenkranz promising Wilson’s art will grow even grander and his life more riotous, the book does not entirely satisfy as a biography. Rosenkranz seems not to have visited any grounds Wilson stomped in order to invest their descriptions with personally captured details. He seems not to have blown the dust from any archives to double-check or supplement his collected facts. He has not drawn upon any outside experts, except other UG cartoonists, to discuss Wilson’s place in "ART." He has not taken up Wilson’s challenge that his panels are too revealing to benefit from psychoanalytic inspection. In fact, aside from delivering some wonderfully cogent and compelling toasts to Wilson’s work (pp. 187-188), he has made little effort to view his life or work through any potentially instructive theoretical prism.

I’ll return to this point, but while I’m griping, I’d like to add that the book’s editing also leaves something to be desired. It would have taken little effort for someone to have learned that the director of The Killer Elite did not spell his name "Peckinpaw." It seems unnecessary for readers to hear twice that an ex-Wilson girlfriend earned a master’s degree for "studying spiders," or to have two different people remark, even eighty pages apart, that Wilson captured his thoughts so quickly, it seemed his pen was appended to his brain.

S. Clay Wilson at Berkeley Con (1973), photograph by Patrick Rosenkranz.

But enough quibbling. Where Rosenkranz’s book succeeds – and here it does grandly – it is as a sort-of oral history. He has interviewed more than thirty people, including Wilson’s sister, not a few significant others, and dozens of good-time buddies dating back to high school. He has woven together portions of these conversations, with selections from interviews Wilson gave over a thirty-five-year period, using his own exposition as a connective, to produce a smoothly flowing, insightful, entertaining portrait of a life lived with exuberance and without apology on behavior’s far borders. (Disclosure: One of those interviews was conducted by me, and a profile I wrote of Wilson is cited among Rosenkranz’s secondary sources.)

Wilson was a great interview, bright, funny, virtually uncensored in thought and tongue, and quicker verbally than anyone I’ve ever met. (Utter a loose word, and he could snap a zinger around it before your sentence was done.) Many of those to whom Rosenkranz spoke are equally rewarding to listen to and he expertly drew them out. Let me quote a few:

Here is Nadra Dangerfield, who lived with Wilson for six years, on the role of art in his life:

(I)t was the way he explored himself, expressed himself, entertained himself, excoriated himself, exonerated himself, celebrated himself.

Here is Murv Jacob, who knew him in Lawrence:

The guy did the best pen-and-ink work of anybody since Picasso... Wilson could see what was going on. He could see over the next ridge.... There was some cosmic shit going on then, and Wilson was right in the heart of it.... It was a dark and bloody century, and he was the one who could see it.... He was a real powerful guy. He scared a lot of people.

Here is the poet/bartender, Rick London, who met Wilson in 1974:

We would drink a fifth and eat a lot of Quaaludes and smoke a lot of pot and do a gram of coke to open new vistas. It seems like a formula for oblivion but not really.... If art is really about discovery, then you’re going to move beyond.

And here, from his introduction, is John Gary Brown, who knew Wilson the longest:

His view of the world came from an isolated, existential place he had confirmed in esoteric books and carefully collected alienated views found in movies, music and poetry. ‘Normal’ life was seen as an ongoing surreal nightmare.

Of course, it is the art that emerged from this defied "oblivion," out of this "isolated, existential place" that makes these words – friends, Rosenkranz’s, mine – of interest. If it was not compelling, none of us would draw a glance. But it was – it is – and here Pirates shines the brightest.

Rosenkranz (and Fantagraphics) have been beyond generous. Nearly every page is given over to pictorial documentation of Wilson’s life or examples of his work. (Over two-thirds of the book's 228 pages are entirely devoted to his art.) There are photographs of Wilson from cherubic child to demonic adult. There are greeting cards he made for his family. (A grade school effort for Father’s Day already depicts a pirate with one arm a bloody stump.) There are strips done in high school. (More pirates, plus outlaws and monsters.) There are college "jams" and grad school oils. There is the portfolio of mayhem that caught Crumb’s eye, and complete stories from the UG’s Zap, Arcade, Gothic Blimp Works, and Insect Fear, and the under-the-UG XXX-rated Bent, Fetch, Jiz, Pork, and Snatch, including the entire "The Felching Vampires Meet The Holy Virgin Mary", which many scholars consider Wilson’s most transgressive tale ever.

Cocks are cut off. Vaginas, mouths and rectums are stuffed. Brains are bashed and guts eviscerated. The Checkered Demon, Ruby the Dyke, and Star-Eyed Stella cavort. Verbal fireworks, from GOOSH to GGGGKKKK to GRRRRWWWLLL to BRATTA BRATA KACHOW KABRI BRADDA VOHANG, explode. (How can one not smile?) All are printed larger than they originally appeared. Their blacks and whites have never looked so fresh and bold. (I am less enthusiastic about the full-page color reproductions. My eye is not my strong point, but to it, they seemed, I don’t know, dull. They lacked, you know, SMMCKL POP WOW!)

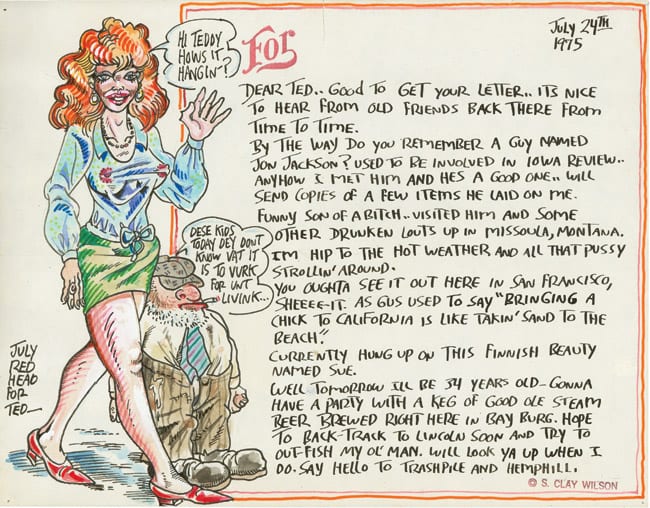

One special treasure in Pirates are Wilson’s letters, which beneficent friends made available. Wilson didn’t just write letters. He hand-lettered them, carefully laid out each one out, and adorned them with drawings, often in color, rubber stamps and paste-ons, so that each became a individualized collagist work. (Boy, do I hope someone is planning a collection of them!) Besides being observed, hey should be read for the five-star Wilson-isms they contain. Who else could think to put down the acclaimed sculptor John Chamberlain, a rival for a young woman’s affections, by calling him, in a letter to her, "a crushed car dealer"?

III

The book’s title triggered another thought.

A mythology is defined as "a collection of myths" and a myth as an instructive story "believed by many people that is not true." And while Rosenkranz quotes Brown as saying Wilson was "very much into creating a mythology about himself," and another friend, Chuck Kinder, saying that "as soon as he got up in the morning he was acting," and a third, Mark Dalton, to the effect that Wilson had a closet-full of "costumes" with which he "played" "this-larger-than-life persona"; and while Rosenkranz himself writes that Wilson, "when faced with a choice between a good story and the facts, always opted for entertainment," I don’t recall one story that was believed by many about Wilson which was shown to be untrue.

Wilson was a striking presence. Well over six feet tall, with a booming voice and commanding manner, eyes were always drawn to him, and his clothes never seemed so much an affectation as an expression of his being, adornment for his body, as ink adorned his pages. No one disputes Wilson would drink until the party’s alcohol ran out – and then leave for another party. No one denies he would spend more on cocaine than rent. He, it is said, "thrived" on LSD, culling its resulting hallucinations for his art. References are made to bars he was 86'd from and a wedding party he destroyed. His wenching was sufficient that he could tell Spain Rodriguez, without contradiction, "I’ve had more pussy than you’ve had hot meals." The only place that Wilson-in-life seems unequal to Wilson-on-the-page is that, whether with fists, flintlocks, or cutlasses, he seems not to have been much of a brawler. But then he never claimed he was. The sole bout he reports occurred in high school, where his emphasis in-the-telling was on how badly he was beaten. Though some degree of showmanship may have existed, the unshakable actuality of Wilson’s carrying-on may explain why Kinder admitted it was "a hard role being S. Clay Wilson," Dalton credits him as "fearless about being who he was," and Brown honors him for providing "those he loved with a vivid, complex, authentic lesson in being alive." (All emps. supp.)

Still, I sought testing for my title-questioning elsewhere.

"I never thought of Wilson’s life as a myth," says the semi-retired Wilsonian scholar emeritus Ruth Delhi, between bites of squid and broccoli in black bean sauce. (Those unfamiliar with Delhi’s previous contributions to my writing – and her dining preferences – are referred to Levin. Outlaws, Rebels, Freethinkers, Pirates & Pornographers, erroneously published as Outlaws, Rebels, Freethinkers & Pirates. Fantagraphics 2005.) "But I always thought his stories were. It felt like he explored the most extreme banks of his imagination, and most people, lacking access to the mental states that led him there, relished the pages he brought back."

I thought about that. The analysis held only if people believed Wilson’s over-the-top stories to be somehow true expressions of his self, which, in a way, I guess they were. For all fiction, while, by definition, a lie, if it is to move us, must ring as true. Something within us must respond to what is, after all, only ink upon a page, as if an actuality is at play. And reading Wilson, whether we feel amused or repulsed, we feel something "happened," even if that "happening" occurred only within the imagination that conceived it.

I was confusing even myself.

"But if Wilson’s work is mythic," I asked, "what’s in it for us? Where’s the lesson?"

"We don’t have to go there!" Delhi exclaimed. "We can live safe lives, while admiring him, as a hero or flag bearer, for exploring a far land that intrigues and titillates us. He has taken a deep, daring artistic voyage, and we can comfortably sit back, writing books and articles, discussing it without risk."

I thought about that.

"Want more squid?"

IV

As an artist Wilson was confident and brash,

but as a person he was just as lost and vulnerable as the rest of us.

John Gary Brown

The ultimate view that the volume delivered was both rousing and troubling. For the "lesson" for which Brown is grateful and the "being" which Dalton respects, and the journey whose results instruct us seem to stem from Wilson’s zest for living, and this zest inextricably intertwined with his drinking and drugging. Wilson’s credo was, Rosenkranz informs us, "‘Don’t water down your whiskey’ which meant that (an artist) should push art as far as it can be pushed.... only limited by his imagination." (Or as Brown said, "Artists don’t insist on knowing the truth. They only want to be free from the bondage that prevents them from reaching for it.") All that is well and good...

...well and good....

...well and good...

Until it ends between parked cars, a cold rain pouring down. "I never realized that it was a problem," Rick London says, "that he wouldn’t be able to stop it when it started to take its toll." I had been with Wilson at a comic con the afternoon of October 31st. He had poured three double vodkas onto whatever he’d walked in with, and I hadn’t realized it either.

Yet for forty-plus years we had the benefit of his work and the pleasure of his company and he the rewards of his achievements. How much would he have traded for a different end? What would we, had we the right and power, traded on his behalf? Those are unanswerable questions, I suppose. Here’s another. Every campus, every boho neighborhood had its "poets" and "artists" who over-edged on inebriants and self-medications, who ended up unpublished, undisplayed, resonating with no one. What enabled Wilson to channel his excesses into glory?

I mentioned "theoretical" prisms earlier. Such analyses are always a crap shoot, but I always feel bereft when an author who has immersed himself in an artist like Wilson hasn’t taken a fling at unwinding the mysteries of the creative process. How did this guy, I always wonder, produce that? My vote is for Rosenkranz to roll the dice in his concluding volumes of this otherwise thoroughly estimable and highly recommended work.