I stumbled onto the work of cartoonist Rick Geary by accident in an old attic in Northeast Portland. I am a huge fan of historical comics and research-based work in general and while I avoid gore and horror in the movies, book-wise I am kind of a true crime buff. So upon finding Geary's Treasury of Victorian Murder series of graphics (published by ComicsLit, an imprint of NBM), I was hooked. I tore through everything I could find at the library. Geary, being the voraciously productive and prolific artist/author that he is, continued to deliver: moving through time into his Treasury of Twentieth-Century Murder series, and adding several comics biographies to the mix. I've often stared at his pictures and wondered at the process of the artist who—while obviously similarly obsessed with crime—managed to present the meticulously documented series of murders and crimes in a non-exploitative, visually appealing way; a mystery in and of itself.

To my delight, over the course of two phone conversations earlier this year, I finally got my chance to pick the brain of this real life, modern-day Arthur Conan Doyle. I'd heard Geary was moving into the realm of Kickstarter-funded publishing and I wanted to find out what the experience was like for someone who was already a seasonally published pro. I wanted to know what drove him to his genre and propelled him towards the completion of so many epic projects. A dream come true, the following is a result of those conversations.

Rick Geary: Well, I'm ready for anything you might want to throw at me. All the pre-interview questions you gave me are all very interesting and were a good outline for where to go, I think.

Annie Murphy: All right then: let's start with the biggie!

[Chuckles] "Why true crime?"

Yeah. Why true crime?

I've thought about it over the years, and I don't know exactly what it is in me that responds to these cases. But it goes back to the early seventies: I was living in Wichita and—I can trace this back to the very genesis—I had this friend who was a cop. And he had this big collection of cop memorabilia, including a pile of old mugshots that he lent to me. And it's just fascinating, looking at all those faces. He also had this complete file of an unsolved case—this unsolved murder that took place in Wichita in the mid-sixties. All the interviews verbatim, and all the police notes on the case, and I just pored over that. I read it from back to front many times and I wrote out my own notes to it. And I think it was--gosh, it was years later when I did my very first comic story for an anthology. And I used that case as the basis for it.

Which anthology was that?

It was published by Kitchen Sink. It was called Fear and Laughter, it was a comic book about Hunter S. Thompson--a take-off of Hunter S. Thompson. And my story was very, very different from all the others in the book. But I don't know, I felt it fit in some way or another.

I'm thinking about these piles of old mugshots, of old photos. To me, that sounds like an absolute delight to go through.

Really? Oh yeah. Oh, these faces ... they stay with you.

Something that appeals to me in your work is the high level of detail, the obvious level of research. It looks like you spend a lot of time poring over material..

Well yeah, I do. I really liked your question [from our initial email exchange] about me being a research geek. That's the stage of the project that I really enjoy because it's a break from being over the drawing board all the time. It's a lot of reading, and a lot of online stuff, and I really enjoy it. Although you know, the deadline structure for these books doesn't allow me the time to really be as studious as I could, by seeking out primary sources and things like that. I usually go to books and articles that are written by people who have really dug into the cases more than I have.

Thank goodness for those people, right?

Yeah! Well I more or less deliberately choose cases that I know something about, but I don't know a lot about. So the research stage is a kind of a voyage of discovery--if you'll allow the cliché—where I get to find out a lot that I didn't know.

One of the questions I had in mind regarding your research was how do you know when to stop?

When to stop? [laughs]

Well, because I am also a research geek, and I love to draw comics based on the research that I do. But sometimes, like for instance with researching genealogy—that's something that can go on a lifetime!

Oh I know, yeah.

So how do you know when it's time to finally sit down and draw?

Usually it's based on deadlines. I always dig up much more information than I could ever possibly put in a book. That's for most of the projects; there are some for which there isn't that much out there. But I always have a lot of detail left over. So it's generally kind of an intuition: when I know that I have enough. There are a couple of books I've done where I thought there would be a lot of info out there, but there just wasn't. So I had to kind of fill it out in the drawing stage, with more full-page illustrations and things like that.

Which books were those?

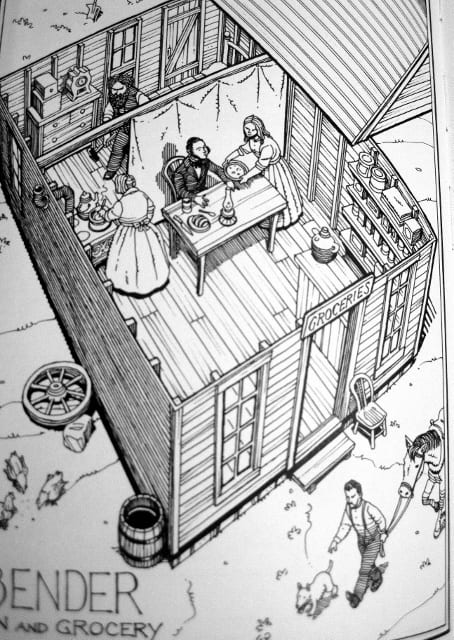

Well the one on the Axe-Man of New Orleans, I was really surprised that no one had written a book about those murders at all. So I had to kind of cobble mine together from a lot of shorter accounts. And also the book about the Bloody Benders. That was a really—well yeah, there really wasn't a lot out there on them either.

Well the one on the Axe-Man of New Orleans, I was really surprised that no one had written a book about those murders at all. So I had to kind of cobble mine together from a lot of shorter accounts. And also the book about the Bloody Benders. That was a really—well yeah, there really wasn't a lot out there on them either.

The Saga of the Bloody Benders. I remember reading somewhere that you grew up near where those murders took place. That they are almost like a part of the mythology of your childhood. Is that true?

Yeah. I grew up in Kansas and Wichita, and yeah, it was a part of the mythology from Southeastern Kansas that I recall from when I was younger.

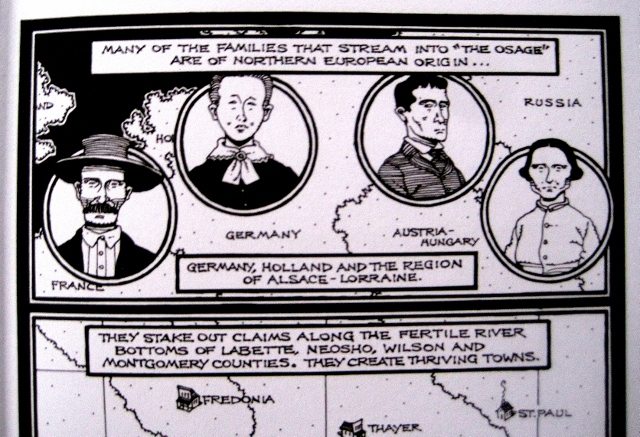

As I said before, I am endlessly fascinated and delighted by the high level of details in your books. I'm thinking about the maps and the insets of the maps. In The Bloody Benders specifically.

I'm just really obsessed with getting that part of it right. I always think about what I would like if I picked up a graphic novel about a true crime, or any kind of historical event. I would like it to be made as clear and have it be as authentic as possible. I love the overhead views and the maps, and making all the movements of what goes on in the story very plain.

I'm curious what sort of feedback you have gotten about this—because some comics readers, they want to move through the story quickly. And your stories of true murder are action-packed but you have a way of presenting information that demands the reader take their time, go through it at their own pace. I love to flip back to the front of the book and examine the maps throughout the read. I love a comic that makes me go back in time, to see what I've missed.

Well, that's nice. I like that.

How is that high level of drawn detail received by the general comics-reading public?

I have to tell you: I don't really know. When I go to the Comic-Con in San Diego or to APE people come and tell me that they like the books, but no one really gets into that level of detail with me. I assume that people who like that kind of thing like it. I don't know if it's for the general comics reader or not. I don't even know who that is.

Yeah, I certainly don't. [laughs] I'm someone who has a hard time reading dense nonfiction cover to cover. So when I want to learn about something, I tend to turn to comics or documentary films. I keep referring to you as the Ken Burns of comics.

[Laughs] Well, I would consider that a great compliment.

But there's also this Sherlockian element to your comics: you lay out all of the information and then you leave it up to your reader to decide.

Exactly. That's sort of my intention.

Sherlock Holmes is pretty big right now—as are detective stories in general. But Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who similarly laid out all of the information for the crime buffs, his glory was to wrap it all up in the end and tell you the answers. He let the reader feel smugness at their own correct conclusions, and shock at the surprises. Whereas, you leave your stories open-ended. What is it about this that appeals to you?

I guess it's just the way my sensibility goes. I like questions more than answers. And I like mysteries more than solutions. I'm a big reader of mystery fiction as well. And I find, in a lot of them the solution is kind of a disappointment. I like being carried along by the mystery of it. Because there's so much in life that's mysterious and I like the idea of laying out all the elements of a case, all the clues, and making that aspect of it as clear as possible. And still it's a mystery. I don't know, my mind just kind of falls in that direction. I don't know how else to explain it.

Well, I consider comics a subjective medium. If it's one creator, they are creating the story, characters, narrative arc, and all of the images. But I've noticed in your books that you do quite a good job maintaining an objective perspective. Is that something you value highly?

Yeah, I try to maintain a kind of journalistic distance. But at the same time, it can't help but be subjective. Because I decide what details to include and what to leave out, what to emphasize. In fact, the very first two books that I did, the first two graphic novels in the series, the one on Jack the Ripper and the one on Lizzie Borden, they were told from within a fiction framework. I don't know if you read those, but--

I did, but it's been a while...

They're both kind of told by this fictional person. The Jack the Ripper book is in the form of a journal being kept by a fictional English gentleman. And then the Lizzie Borden one is from the point of view of this woman I made up who was supposedly a neighbor of the Bordens, a friend of the Bordens, who was telling the story. And after that one my publisher came to me and said: “This is kind of a problem. It makes the books fall into this crack between fiction and nonfiction, and they don't know how to classify them.” So from then on I adopted more of a journalistic outlook. Or as close as I could anyway; more of an objective viewpoint.

That's hard to do.

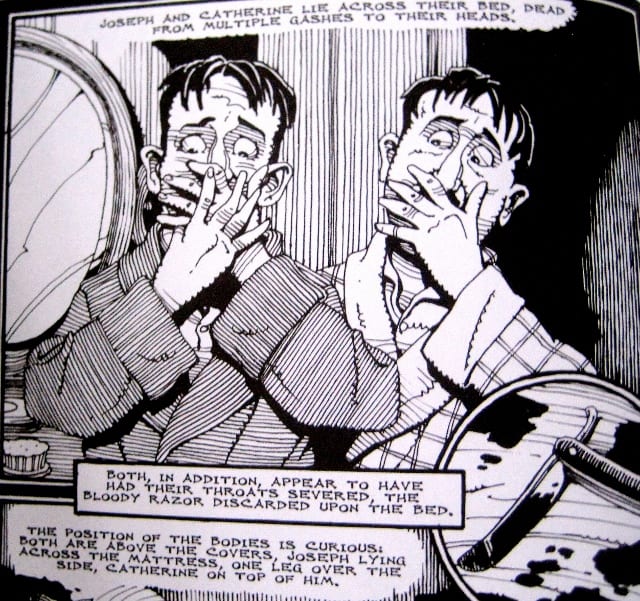

Yeah. Well, I try to keep a little ironic distance from everything. I'm not into blood and guts or the sensational aspect of it so much.

I love that about your work. It's allowed me to continue reading your books. I'm attracted to true crime stories and yet I have a soft stomach for gore and violence.

Well, I don't mind it in other people's work. It's just that in what I do, I tend to pull back from that.

If you draw as much as you do, your subject matter ought to be pleasing to you. You draw a lot of portraits, maps, diagrams—have you always enjoyed drawing those sorts of things?

Yeah. I guess it goes back to when I first started what I though of as a career in art. I was working for weekly newspapers back in Wichita and I was called upon to draw all kinds of things every week, including maps and charts, overhead views and things like that. And that kind of just spilled over. It's something I really enjoy.

You also tackle some weighty political subjects.

You also tackle some weighty political subjects.

Yeah, I have a few of those. That's not a major concern of mine, the political content of some of these stories. Just whatever tangential connection it has with the mystery is all that I'm interested in. Like, in Sacco and Vanzetti's story, the politics of their case is hard to avoid. But I didn't think of it as being central to it. And the same thing with a couple of other ones that I've done, like the James Garfield assassination.

I recently read your J. Edgar Hoover biography, the Trotsky one, and the Lives of Sacco and Vanzetti in succession. That was like a crash course in the history and politics of that era.

[Laughs] Whoa, that would be a bit overwhelming all together.

Actually it was a great way to get multiple perspectives at once on similar issues.

Well with Trotsky and Hoover of course, there's no way to get around the politics of that. I thought it was kind of a nice balance. You know, I didn't choose either of the subjects, they were assigned to me. But they made nice polar opposites; made the research end of it more interesting and entertaining.

I originally learned the story of Sacco and Vanzetti in high school as kind of a study in the way the justice system works.

That's interesting! I never got that in school at all.

I went to a hippie alternative public school. It struck me during my read of the Sacco and Vanzetti book just how relevant to the current times it is, even though it takes place in the 1920s. I was reminded intensely of the case in Georgia of Troy Davis. In fact, your Sacco and Vanzetti book came out the same year as Davis's execution.

Well, it just hasn't stopped. There's this rush to put people to death no matter what, it seems like. You read about stuff like this happening in Texas all the time. It just hasn't changed.

Again, this goes back to your books. What motivates people and systems toward this sort of violence? Is it institutional, is it familial, is it just some kind of random occurrence?

Well yeah, that's another mystery. Even though we think we might be able to get to the bottom of it, the human mind is just this labyrinth. It's not easily explained or understood. That's another part of it that fascinates me.

Most all of the hardcore comics buffs I know know who you are. But a lot of my friends don't and they kind of take a step back when I tell them they should read your stuff. It's like: “Why is Annie recommending all these murder books?”

[Laughter] Weird..

Who knows where our preferences come from, right?

Oh, exactly. Without spending time on a psychiatrist's couch. I mean, you gotta just take 'em for what they are.

[Laughs] I'm always curious to hear what sort of things influence the particular drives behind the madness of cartoonists. Can you list some things, particular books, movies, obsessions--outside the field of comics--that inform your work?

Well as I mentioned, I'm a voracious reader of mystery fiction. I have been for many decades. And I'm also a big movie-goer. In fact I wanted to be a filmmaker at one time, in my college days. But I found that comics fulfill that need for me. You can be writer, director, actor, and you don't have to leave your room.

There are so many artists I can think of who have influenced my work—but not in any overt way, they just kinda seep in. Filmmakers like Hitchcock of course, and Orson Welles. Nowadays it's the Coen Brothers. Gosh, there are pen-and-ink artists from the turn of the century whose work I really admire. There's this ease and flow to their work. People like Winsor McCay and Franklin Booth (he was one of the great early illustrators). I don't know, there's just too many people to mention. But everything you encounter kind of goes into the hopper and floats around and mixes around in there. And it comes out in one way or another.

Do you read comics?

Not in any regular way, no. I'm always kind of hesitant to tell people that growing up I wasn't ever a big comics fan or comics collector. They weren't a big important part of my growing up. I only kind of came to them later in the underground comics of the sixties and a lot of the alternative comics that came around later. There are some people who are around today whose work I admire, but I don't really read a lot of comics to tell you the truth. What draws me into a comic, when I happen to be in a comics shop is a distinctive and compelling visual style. And that'll make me keep turning the pages even if I don't get into the story.

I'm the same way. I can't get into a story if it's not done in a compelling visual style. Like with your work—I love to stare at the lines. It looks like you get joy from making lines in ink.

I love the process. Once a project is finished, I just let it go and don't even consider it any longer. I like getting on to the next thing. It's kind of ritualistic in a way. I just really enjoy sitting at my table and drawing. It's what I've always done. I've progressed over the years into using the pen line to create more of a three-dimensional look to the people and objects that I draw, doing shading and texturing and molding—I didn't used to do that at all; it was just plain linework. All outlines.

It's nearly psychedelic. I have an appreciation for pictures I can get lost in. There's a magical quality to it.

I don't know. It just is what it is. I can't explain it.

I fill everything in black. That's my pleasure.

I've been getting into that a lot lately too. I love the solid blacks. If it's not fun, why bother?

Do you mind if I jump subjects a little? I wanted to ask you about your Kickstarter campaign process.

I did two projects this last year. One went off a little better than the other, but I still think it's a great process and I'm going to be doing another one I think, this year. You said you did a couple of projects?

I have, I've done a couple. And I know there are a lot of people debating the pros and cons of these sorts of crowdfunding sites. It seemed like a great next step for someone like me, a broke artist coming from a DIY background who may or may not get published at all if I didn't do it myself. But you are someone who has been published by others for decades. What is it like switching to the independent publishing platform? Or have you done that before?

Not to any great degree. I kind of got my start back in the seventies self-publishing some little comic magazines; not on any large scale at all, but they did get me into National Lampoon. Some of the editors there saw them. And recently I'd been hearing from people about Kickstarter, and I just thought I'd give it a try. I did this short true crime graphic novel [The Elwell Enigma] and the initial phase went really well. I got much more than my goal and got the book printed, and then the part came where--

The dreaded part?

--Where you have to kind of give people back what they came for.

Did you have someone helping you manage your campaign?

Oh yeah. A friend of mine named Mark Rosenbohm who lives in new Orleans. And he's been my tech guy on a number of projects. He's the one who managed the Kickstarter project for me. But when it came to actually fulfilling all the premiums, that was my job. Because I had all the books sent to me. So I sent out the books with, well—on one level there's a drawing, an original drawing in the book and then some people got original pages of art from the book; and some people got their portraits drawn into the story and stuff like that. After the books came out it was a good three months before I got everything sent out.

I would say that's a pretty good turnover.

It wasn't as horrible as I thought it would be. I'm thinking there are a lot of kinks to work out, and I think you can only do that by doing more projects. There was one that I did last fall that wasn't really a comic book project, it was more a book of illustrations. And it didn't quite reach the goal that I was hoping it would.

I think it's fascinating to see more well-known artists turning to Kickstarter. It's almost as though they have more creative control that way.

Oh, absolutely. Yeah, you manage your own project and it's more of an independent feeling. The only other downside is that now I have all these boxes of books that I'm gonna have to sell off gradually over the years. I'll take them with me to comic cons and sell them from my website, but I don't have any major distribution apparatus to do anything more than that.

Is that the “Obama's Alphabet of the Antichrist”?

That's still at the printers. It hasn't come out yet but I have a feeling... I don't know. I'm in this experimental frame of mind with Kickstarter. I just want to see what will happen.

It's all new ground being broken.

Yeah. I kind of like the feeling of being my own publisher, even though it's still a minor corner of all that I do.

Dang. Getting two books done via Kickstarter on the side, and you're also getting books out for publishers.

Dang. Getting two books done via Kickstarter on the side, and you're also getting books out for publishers.

Maybe I'm a fast worker, I don't know. But I'm at my drawing table eight hours a day. I just do everything that needs to be done within that time frame. I don't go overboard—I don't think.

Do you keep a pretty strict schedule with your work?

I'm pretty tightly structured in that regard, yeah.

I met your wife Deborah some years ago at APE. Is she a supporter of what you do?

Oh yeah, she's a big supporter. I think she's gotten better at it over the years—she's not a big comics person. But she enjoys meeting people and going to the different events. San Diego and APE in San Francisco, those are the only two we really go to.

Are you going to continue going to San Diego [Comic-Con]? I've heard some people say it's getting too big.

It is too big. But God it's a great event, I love it. It's overwhelming.

Those are your stomping grounds, right?

When I first moved to San Diego I knew I wanted to be an artist of some kind--or a cartoonist--but the idea of making a living in comics was just really far from my mind at that time. And I fell in with these people at the Comic-Con and then everything kind of snowballed from there. So it's been very important in my career.

So... do you make a living from comics?

Yeah. Yeah, comics and whatever else comes along; I do illustration work for magazines, newspapers. I just pretty much take whatever comes along. And it's not always been the best living, but I don't know how to do anything else.

Well, I for one am grateful for that fact. I feel like I looked away for a few years and when I looked back you had twice as many books. Which was great because when there's an artist I love, I just want stacks of their work to devour. And you must just have stacks of books and anthologies you've been published in.

Oh yes. No doubt about it.

Do you have more Kickstarters coming up?

Actually yes, I'm working on a project that I hope to try to get funded later on this year. But I want to get the project going before I do that. It's another graphic novel, so hopefully it'll be more of the kind of thing I'm known for, that people will want to contribute to.

Remind me of the biography you wrote of the guy who was kind of an aristocratic con man, what was that called... Catan?

Remind me of the biography you wrote of the guy who was kind of an aristocratic con man, what was that called... Catan?

Oh, Cravan. Arthur Cravan. This was a pet project of Mike Richardson at Dark Horse. I don't know why but he identified with this guy in some ways, a mysterious fellow. So he did a lot of the research on his life and just handed it over to me to fill out the script and design the comic.

Do these "pet projects" usually fall under the realm of Kickstarter? Like, you've got NBM who is continuing to publish your work too, right?

Oh yeah. Actually what I am working on now for them is a bit of a departure: it's a mystery fiction—like a murder mystery. After that I'm gonna go back to the true crime. But I thought I'd give this a try. That'll probably take me the rest of this year to finish.

Does the fictional impulse come from wanting to fill in those blanks?

Gosh, that's interesting. I don't know that I want to fill in the blanks. The fictional piece that I'm working on now is more like a conventional murder mystery in which this one character plays detective and does finally fill in the blanks. But it's a long, slow process. And yeah, there's a different kind of satisfaction to that than doing the true-life cases. I'm very satisfied with a mystery remaining a mystery.

And you aren't Kickstarting that one...?

No, this is with my publisher who brings out the Victorian and twentieth-century murder books [NBM/ComicsLit]. He's the one that suggested it to me: that I try doing a work of fiction. And I said why not? I'd love to try it. We'll see what happens.

I'm curious to see all that material in your brain fictionalized, to see what happens there.

Well, I'll be interested to see how it comes out as well. But for my next Kickstarter project I'm doing something about Billy the Kid, who is a big personage in this part of the country where I live.

Well, I'll be interested to see how it comes out as well. But for my next Kickstarter project I'm doing something about Billy the Kid, who is a big personage in this part of the country where I live.

And that's one of your personal projects?

Yeah, this is more of a personal project. It has murder and violence in it but it's not a murder case. It's more of a broad history, I think.

My favorite late-night TV show to watch is PBS's American Experience.

Yeah, there was a show about him [Billy the Kid] just recently. I dunno. It was factual as far as the writing went, but the reenactments were kind of ... not too authentic to say the least. The visual aspect of it.

[Laughs] And were you prompted to want to do your own version then?

Oh, I've been wanting to do this for a while, since we moved here to Lincoln County [the area of New Mexico closely associated with Billy the Kid] seven years ago.

I've noticed that among artists who do similar research-based comics work, sometimes there's this fear of being discouraged by work that has already been created about the subject the artist wants to focus on.

Yeah. That never discouraged me. I know some of the books I've done are about cases that have been—you know, there's just too much out there! People have been writing about them for years. But one other take on it doesn't hurt, I don't think. Another viewpoint.

Do you have advice for insecure emerging artists out there working from source materials who may get overwhelmed or discouraged by the material already in rotation?

I'm not sure about advice. But I would say, go ahead and do it. If it's something that fascinates you, you will bring your own personal viewpoint to it, and it's bound to be something unique. It will add to the literature. That's certainly been what I tell myself when I start.

I wanted to ask you about the Axe-Man. [The Terrible Axe-Man of New Orleans, ComicsLit/NBM, 2010]. You can't talk about this story without talking about place. Do you have a personal connection to the city of New Orleans?

I don't really have any personal connection, no. I luckily have some friends who live there and while I was working on the book I got a chance to visit there. They showed me around and really had a great time. They were the ones that went to the library and dug out—I guess it's not microfilm anymore, it's all on digital--all the old headlines from that era. They found them for me and it was really helpful. It was really helpful to go there. In all the books I do, they are all specific to a city. And it's always nice to be able to actually go there and soak up the atmosphere, although I haven't been able to do that in too many cases.

In the bibliography of the book it reference the Times-Picayune. I've done some digging around in historical societies and archives for comics projects I'm working on. Where did your informants go to find their information?

As far as I know it was the public library in New Orleans there. All that was on file, if I'm not mistaken. I believe they've got a pretty extensive, pretty complete file of newspapers there from that era. And it was nice to see photographs of the original settings; because none of them really exist anymore. When I was visiting there, they drove me around to some of the intersections and the streets where the actual crimes took place but none of those buildings are around anymore, as you might imagine.

A lot of the buildings you drew looked kind of ramshackle...

Yeah, and this was just after Katrina that I went there. And there was just a lot of stuff that had been destroyed.

Wow. Of course. Did your friends send you articles one at a time?

No, I think that they sent it all in a big package, all that they could find on the murders. They sent me as much as they could. They had them printed out and just sent them in an envelope through the mail.

What did you do when the envelope arrived?

Well, I'd had a lot of the story written by then. Plus I'd done some of the artwork. And it was just good to go back and make corrections. Some of the buildings I redrew to make them more in-tune with the New Orleans-style architecture; and redrew some of them that looked like the actual buildings too—there weren't that many left I guess. And then there were some anecdotes in the newspaper articles that I incorporated into the story that I hadn't read before in any other source. One of the truisms that I always keep in mind is that: newspapers are the first draft of history. They get it fast, but it's not always correct. And a lot of the facts don't really hold up over time. But they're good to give you a kind of sense of what was going on at the time.

With the data you were collecting, were you able to iron out some of those wrinkles in history?

Yes, actually. Because with one of the Axe-Man murders, there were some of the inter-relationships among the characters which were kind of confusing in the reports I had read that the newspaper accounts straightened out for me a little...hopefully [laughs].

Well, I read it right before bed and it was a bone-chilling story. How did you first hear about it?

I must've come across it in one of the crime anthologies that I have. I've got two or three of them that just give short accounts of famous cases. And this one appealed to me because it was unsolved of course. And then when I tried to find out more about it, I found there really wasn't that much out there. No one's ever written a complete book about the Axe-Man case. Someone should!

Well, you did.

It just seemed like sure-fire material to me.

And has anybody written anything on it since?

Not that I know of. That's really strange I think, because it's a really compelling story.

It kind of reminds me of one of the famous unsolved murders I follow, the Black Dahlia murder.

Oh! Actually, that's going to be my next one.

Oh really!?

As soon as I finish this one I'm working on now. Yeah, that's always fascinated me too.

Oh wow, I'm so excited. I know there's been movies about her, about Elizabeth Short [aka the Black Dahlia], and a lot of references to her recently in pop culture. Those murders are a little more well-known. But when I first heard of them it was through a very obscure reference in a really terrifying "true" ghost story a friend told me. There were all of these coincidences between her tale and the Black Dahlia story. I've been kind of obsessed ever since. Everyone has a different idea of who her killer was, and something about the Axe-Man reminded me of that. I think because there was such a method to the murders, the similarities...

And it had the musical element, too.

Yeah, talk about that. Because that part really struck me.

That struck me too, definitely. And even though a graphic novel isn't a very musical medium, I felt that as a kind of a theme, a leitmotif that could float through the whole story. Apparently someone wrote a song about it, I wish I could track that down...

An older song?

Yeah, it came out around the time. “Axe-Man's Jazz”, it was called.

That's kinda like—what's the song with Billy? “Stagger Lee”. Stagger Lee shot Billy...

Oh yes. There's a true story buried in that song too; a friend of mine asked me if I would do that some day. That took place in the 1890s in St. Louis I believe, or Chicago. I can't remember.

For readers who might not have read the Axe-Man, will you tell the part of the story where music really collides with the path of these murders?

Okay. It started with a letter that came into the Times-Picayune. This was after a period where the murders had stopped for a while and people were kind of getting back to normal. And then a letter was published in the Times-Picayune, supposedly from the murderer. You know no one was able to confirm that it actually was, but the guy said he was going to be out stalking on this particular night. But anyone who was playing jazz on that night would be spared. And so the whole city was alive with music on that night. And the murderer, for one reason or another, never struck. So that was a very strange and compelling episode, I thought. Now whether it was just a series of coincidences or whether it was actually orchestrated by the killer, I don't know. We'll never know.

We'll never know. Something I notice as we discuss your modes of research, it's almost like the whole process is a suspense story unfolding—for you. Do you feel like that when you are researching--that you are basically in your own suspense story turning one page after the other to see what happens?

Actually, yeah. I mean, there are some cases that I know a lot about already. But there's always something new to be found out. And with a case like the Axe-Man, or a couple other ones I've done where there isn't that much out there, I go far afield to find source material. But yeah, it is like participating in a mystery. The clues keep popping up and it's fascinating. I love it.

Does it keep you up at night?

No. I'm a pretty early riser actually...

Well, does it get you up early in the morning?

Yeah, it does. Because I just love the process of it.

I'm thinking about the night the Axe-Man made everyone play jazz: if they didn't have a phonograph or instruments, they had to make instruments to play. Reading about that was like getting a look into another world. I love those sort of time portals.

Oh, I do too. It is fascinating to see. To kind of try to form an intimacy with how people lived back then. It's an intuitive thing, you know? You can do a lot of research, but you kind of have to feel it.

What intuitive hints are you getting from the Billy the Kid project? Are there any main themes characterizing that era that especially stand out to you?

Since I've been living in New Mexico you know, I've never—it's kind of a wild place even yet. And I've been really trying to get into this frontier mentality. Everything was just kind of raw and untested here. People were making life up as they went along, I think. And that's kind of the mindset I've been trying to get into with this Billy the Kid book. He's just been so shrouded in legend. I'm trying to form a picture of him as he really was, trying to make it as authentic as possible. There are a lot of books out there and maybe a handful of them really treat him factually. I'm still in the process.

What I would give to be in the same place with you for an hour or two and talk only Black Dahlia lore. You know the book called something like “My Dad was the Black Dahlia Murderer” or something?

Yeah, that one I know.

Well, there's another one, written by an ex-LAPD detective where he stumbles on these old scrapbooks in his dad's stuff and winds up attempting to prove that his dad was the killer. I was thoroughly convinced. It's just called The Black Dahlia Avenger [by Steve Hodel]. I think you'd like it.

Oh yeah, well I'm going to be really diving into all the literature about that for sure.

Keep you eyes peeled: Geary's Billy the Kid Kickstarter goes live July 15th.