What does an American with the powers of a god do when the country goes to war? Sure, he bats away a few enemy battleships and plays baseball 30,000 feet in the air with a couple of their war planes, but the really important things he does are… deliver mail, peel potatoes, and play matchmaker.

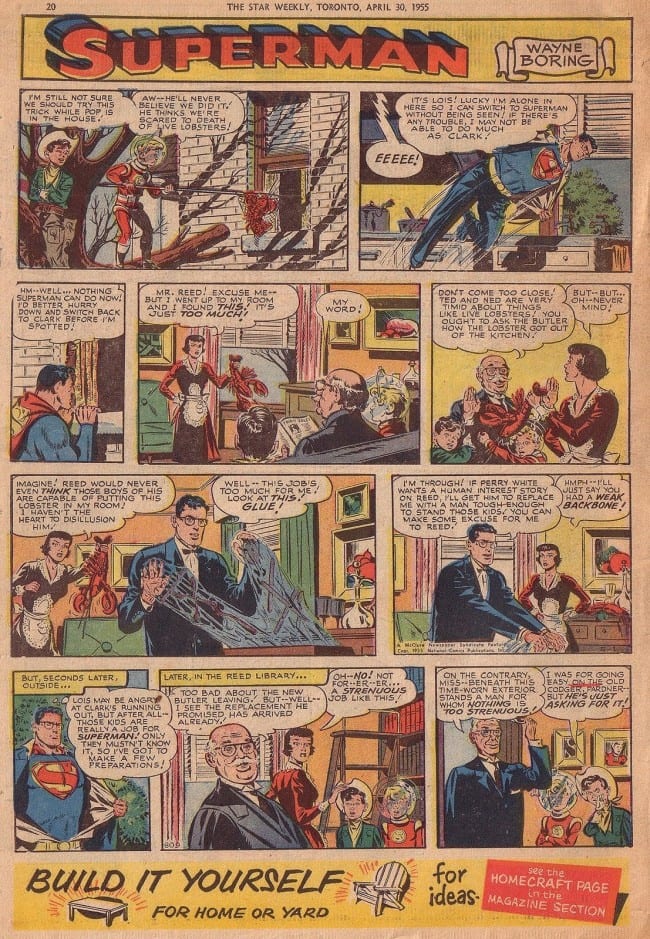

The Sunday newspaper comics collected in the handsome new IDW collection, Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943-1946, mostly deal with Superman’s involvement in World War Two, and chart not only the war years of the classic newspaper comic, but also the inevitable (and entertaining) trivializing of the Superman concept that would lead to a 1945 comic book cover in which the Man of Steel used his super breath to defrost Lois Lane’s refrigerator.

The problem was that, in the four-color world of the 1943 Sunday newspaper comic, Supes could conclude World War II in a single strip, but the war would still rage on in reality – and the fantasy would be broken. In fact, Superman did end the war in 1940 (fictionally speaking), in a two-page story that appeared in the February 27, 1940 issue of Look Magazine, in which he scooped up Hitler and Stalin and turned them over to the League of Nations. (This feature was created nearly two years before America entered the war and it shows Hitler and Stalin on the same side. Germany violated a pact with Russia in 1941 and Stalin joined the allies.) This Superman story, however, was only a hypothetical fantasy-within-a-fantasy story (the first of many to come) -- and therefore had no lasting impact on the actual Superman universe.

By 1943, the man that started out leaping over tall buildings was now able to fly around the world before you could say “Look! Up in the Sky!” In 1938 Superman started out lifting cars over his head. By 1943, he was balancing battleships on his pinky. He was not only super-strong, he was indestructible. And, he could melt a tank just by looking at it. This guy was preposterously bad-ass. Or, was he?

His creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, originally conceived of Superman as a “humor-adventure” comic strip. That’s the exact phrase found on a page of miscellaneous drawings from an early brainstorming session. In an interview published in Nemo #2 (August, 1983), Joe Shuster observed, “Jerry and I always felt that the character was enjoying himself. He was having fun; he wasn’t taking himself seriously. It was always a lark for him...” Humor, then, is part of Superman’s DNA as much as super-strength and the ability to see through things like, say, women’s dresses (something he does in the 1978 movie, Superman, starring Christopher Reeve). It's that kitschy contrast between heroism and humor that drove the Superman comics of the 1940s and 1950s.

If Superman couldn’t end the war without shattering his intoxicating, money-making fantasy world that marched in rudimentary synchronization with contemporary American life, he was nonetheless obligated to get involved in the effort that touched nearly every American in 1943-1946. As Mark Waid writes in his introduction to this collection, “But if he sits the war out, what kind of man – what kind of Superman, what kind of American – is he?” Since it became necessary to send Superman to war, a way around his ability to end that war was needed. The answer was found in the long-running "Superman's Service for Servicemen" saga that ran from strip 200 (August 29, 1943) to strip 316 (November 18, 1945), comprising 117 of the book's 169 Sunday pages.

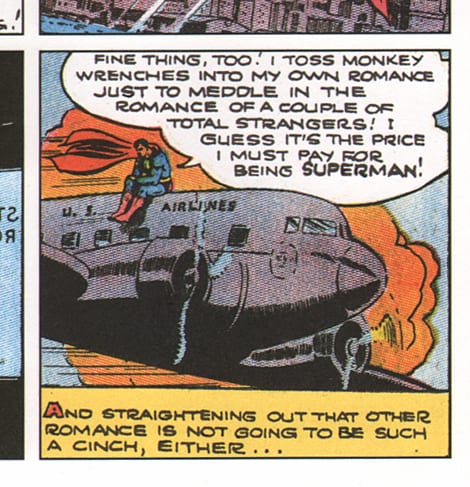

The Sunday page on August 22, 1943 ended with an invitation to men and women serving in the conflict to send in their own problems for Supes to solve. For the next two years, Superman continually flew from the good ol' United States to the front lines of the war in the European and Pacific theaters, using his super-powers to deliver mail, perform soldiers' K.P. (kitchen patrol) duty, and resolve romantic tiffs. Anything to keep our brave men and women happy. Superman's decision to stay on the sidelines of the battles only made the soldiers seem more heroic and capable. In one memorable sequence from November 21, 1943, two Marines named Lunk and Bob take on 300 attacking Japanese soldiers, and assure Superman they have it well in hand. "How can you beat soldiers with that sort of spirit... for me to interfere would be -- well, presumptuous." Superman exclaims in patriotic fervor.

D.C. editor Whitney Ellsworth, who played a large role in shaping Superman as the iconic symbol of Truth, Justice, and the American Way, is credited by some comics history scholars as conceiving and writing this long segment. It's entirely possible, as Jerry Siegel had his hands -- and typewriter -- full, turning out stories for the comic books and the daily newspaper strips (which had completely separate continuities from the Sundays). In any case, the absurdity of the situation was not lost on whoever wrote these strips. Superman often grumbles about his menial tasks, and in one episode, he is seen sulking while sitting on top of a flying passenger plane.

Of course, Superman has to confront Hitler at least once in this series, and so he does, in a wonderfully nutty sequence that involves the woefully out of shape Nazi command donning Superman suits. After all, they were the super race -- Neitzsche be damned.

In other sequences, however, the comedy and displays of super deeds are played down and a comic strip version of military life comes to the forefront. Early examples of the sort of personalized war stories that would soon become a staple of American war comic book titles, these pages, while not particularly precise in their details, have a sincerity beyond the typical Superman story.

In general, the Sundays were written for an older audience than the comic books, and reached -- however clumsily -- for a slightly more adult treatment. In one sentimental sequence, Superman flies a critical father to the front lines, where he discovers that his son is a respected, fierce warrior. Time and again, in these stories, Superman is a fatherly Odin figure, who carries mere mortals in his arms like babies in order to solve their personal problems.

A word must be said about the horrendous portrayal of Japanese citizens in some of these pages. Sadly, these stories fall into the same racist and stereotypical template seen in other comics of the period. Japanese people are drawn as bug-eyed, buck-toothed idiots who can barely speak. In this way, the war-time Superman strips represent American propaganda, dehumanizing the enemy. To read these pages from the perspective of a 21st century American is to painfully confront our own tarnished heritage.

While Joe Shuster’s name is on every Sunday page in this collection, he probably had very little to do with the art. While some of the early pages in the volume are by the talented Jack Burnley, the majority are by Wayne Boring, who developed what many feel is the definitive Superman figure. Boring ghosted many of the early Siegel and Shuster comic book features, including Slam Bradley and Federal Men, which he was allowed to sign a couple of times.

Wayne Boring eventually moved to Cleveland and worked in a small production shop that Joe Shuster ran, devoted exclusively to churning out Superman comics to meet the super-demand. While he drew the occasional cover and story for comic books, Boring's main job was the Superman Sunday. which he penciled, inked, and even lettered. Boring gradually beefed up Superman, making him taller than average, broad-shouldered, and with the waistline of a mature man. Jim Steranko described Boring's version of the Man of Steel as "a massive, muscled version of virile exuberance." Animator John Kricfalusi has said that he regards Wayne Boring as the best Superman artist "because he draws everything so wooden." John K. also observed that Boring's Superman has a larger jaw than cranium. It wasn't until Siegel and Shuster lost their lawsuit and then their jobs at D.C. in 1948 that Boring got a byline on the newspaper strip.

Boring, who worked directly for D.C. Comics starting in 1942, created several memorable covers featuring the Man of Steel. One of Boring's most graphically sophisticated works was his psychedelic cover for Action Comics 89, published in October, 1945, which looks as if it were published in the 1960s!

Under the pen name "Fred Harmon," Boring also drew several stories for Novelty Press comics, including some stories featuring the blonde-haired Superman knock-off, Blue Bolt, and the sexed-up Lois Lane doppelganger, Toni Gayle.

The two-year saga of "Superman's Service for Servicemen" ends with strip 316, on November 18, 1945, as World War II wound down. The remaining 35 pages in Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943-1946 offer a return to normalcy, if one could call it that. Starting with a four-Sunday retelling of the Superman origin story, probably drawn by Boring for the first time, the series then inserts Lois Lane into a rocket and launches into a futuristic space opera, a la Buck Rogers, one of the prime influences on Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster when they created Superman. While Whitney Ellsworth likely scripted much of the wartime saga, the strips in this period returned to that giddy, visionary, Borscht Belt comedian feeling that only a comic written by Jerry Siegel can have.

The volume concludes with the goofy, compelling "Sadface," probably the strongest sequence in the entire volume, in which a clown must prove his love for a sexy trapeze artist by performing death defying feats of courage. Lucky for him, Superman is nearby to secretly help out. One breathes a sigh of relief at this point in the book to be able to get away from enemy lines and back into the more entertaining psycho-sexual territory that underlies the Superman mythos. The clown story is doubly interesting if one knows that Siegel and Shuster left D.C. Comics and Superman in 1948 and created a new character -- a clown-hero named Funnyman.

In 1999 Kitchen Sink and DC Comics issued elegant hardcover editions of the first years of the syndicated daily and Sunday Superman comic strips. Now, nearly 15 years later, Dean Mullaney, his team, and Mark Waid have picked up where the series left off, making Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943-1946 volume two in the collection. Where the first book is in a horizontal format (or, for newspaper comic collectors, “half”) format, the new IDW volume is vertical (tab). A note from Dean Mullaney in the new volume states the intention to produce a matching vertical edition of the first years of the Sundays when the rest of the series has been reprinted.

This book is part of IDW's Library of American Comics, a vitally important archival project led by the indefatigable Dean Mullaney. Thus far, every volume in this series has offered a virtually flawless presentation and Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943-1946 is no exception. The book improves on the classy Kitchen Sink/DC Comics volume by including the strip number and date for each page. The restoration and printing are state-of-the-art. An insightful, if brief introduction by Mark Waid sets the stage. The oversized volume presents the comics at a slightly smaller size than the original, but still perfectly readable (thanks in part to the strip's excellent lettering). The front and back covers feature appealing new art by Pete Poplaski, who also created the elegant dust-jacket and endpaper art for the 1999 Superman Sundays collections.

The Superman Sunday newspaper strip continued until 1966. The comic books and movies starring this iconic figure continue to this this day. The creators and mechanics of the myth did not fare as well. In 1975, Joe Shuster was legally blind and destitute. Jerry Siegel was working as a clerk-typist to survive. Comics fandom took up their cause, and eventually DC Comics agreed to pay the creators, who had sold their rights to Superman away years ago, a yearly stipend of $25,000 each. Wayne Boring, after being the chief artist on Superman for decades, was abruptly fired by DC in the late 1960s. He left comics for painting and in his last years he worked as a security guard. In an interview conducted during this time, he said, "I'd like to get back to drawing, now that you mention it..."

This collection of what editor Dean Mullaney has called "ridiculously rare" comics (finding a complete run of the strip is harder than getting Mr. Mxyzptlk to say his name backwards) is something special. It’s a recovered piece of cultural history that is goofy, grand, racist, and revealing. Even more, it's a chance to read a large, mostly forgotten chunk of Superman in his glory days, when the concept was fresh and the energy was pure.