From Against the Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood. ©2003 Bhob Stewart

Wallace Wood photo was taken by Bhob Stewart.

“See you in the funny papers.” — 1930s catchphrase

“See you in the darkness.” — Gary Gilmore, January 1977

Worlds were created while the radiator clanked. On the crescendo streets below, junkies trudged beneath crimson neon toward Needle Park. But, in the silence of Wood’s Studio on West 74th Street, in 1968, ink flowed in perfect curves with no ragged edges.

One night I broke the silence: “Why do you do this?” I saw Wood’s back twitch, startled, as he realized what I was getting at, but he continued inking Superboy and didn’t turn around. Ralph Reese remained silent, delicately bringing up a background on another page.

“Why do I do what?” asked Wood.

“This superhero crap. My God, you’re as great as any of the world’s greatest humorists. No one can do what you do the way you do it in your writing and your art. It’s your own. So isn’t this inking job just a waste? What does it have to do with you?”

The truth of this hung in the air, and then spiraled away. There was no prolonged response or discussion because there was, we all knew, no answer that quite fit the circumstances. Later, a country music station played “Streets of Laredo.” The ink flowed into the night.

Wallace Wood would have loved the headline the Los Angeles Times ran above his obituary: “Gut-Level Characters Made Him Famous,” a pun referring to his ad for Alka-Seltzer. I can imagine him clipping this obit, leaving it on the upper-left corner of his drawing table, and squinting at it occasionally while continuing to quietly ink panel after panel after panel. Someone who leaned over his shoulder to glance at the headline might make a remark about the importance of media attention; this would prompt only a smile and a muttered, “Yeah, but they got that part about the TV commercial wrong.” Later, the clipping would vanish from the drawing board into one of the dozens of file folders of work by and about Wood — all labeled “ME” — in his filing cabinets.

I remember the week Wood sketched the storyboard for that commercial (which LA Times writer Dana Kennedy calls his “best-known work,” while confusing it with the printed advertisement). The full-color “Stomachs get Even at Night” ad, showing angry vegetables preparing for a midnight attack inside a stomach, had caused a sensation at the ad agency after publication. Had Wood picked that moment to acquire a top agent, possibly, he could have ridden the wave all the way in — but even when the surf was up, what he sought was that perfect, impossible wave.

For TV, the agency wanted the vegetable characters to do something, despite the frozen moment of anticipation that gives the print ad its tension. And so the storyboard — which looked like he had whipped it together in an hour — introduced a human character, a shocked guy in striped pajamas, leaping off the sheets as vegetables march across the bed. The dark strangeness of the original concept had been sanitized for TV. The difference bothered me, but I didn’t remark on it.

“Are you going to follow through on this?”

“How do you mean?”

“Well, are you going to protect it? Make sure they animate it in your style?”

“No,” said Wood. “Why bother?”

I was baffled by this attitude, but said nothing. The board was delivered to the agency, and Wood moved on to other projects. Months later, at an impromptu party in Washington, I glanced at a TV set flickering the opening of the commercial I had not yet seen. I quickly explained to everyone present that it was by Wood, and we all watched. No one reacted. Whatever was artful in the storyboard — already a dilution of Wood’s original, imaginative concept — had now dissipated completely.

Many of Wood’s projects were like this — a brilliant flash of intensity that soared and skyrocketed before arcing downward to sputter into nothingness. Compared to the famous R.O. Blechman Alka-Seltzer commercial about the talking stomach, and the other popular Alka-Seltzer commercials of that period, this one was disappointing and forgettable. The animation was TV-routine, and the characters had lost Wood’s comic malevolence, replaced by mere cuteness and silliness. Did Wood, I wondered, know the battle was lost even before he drew the storyboard? He once said to me, “An editor is someone dedicated to destroying the work of a creator.” His interest in self-publishing developed out of a genuine feeling that he was being victimized in the commercial world.

The first I learned of Wood’s problems was in the early ’60s. “Wood has these terrible migraines,” said Larry Ivie. “He draws for an hour or so, gets a headache, lies down and then does no work for the rest of the day.”

But this wasn’t evident to me when I started working with Wood a few years later. Free-floating in 1967 — after leaving an editorial job at TV Guide — I mailed him some samples, and he invited me over. At that first meeting I was shown a stack of pencil sketches — psychological cartoons was the only thing to call them — that indicated how his talent outstripped his markets. (One of these sketches was his “Mother” drawing, later incorporated into his “My Word” story for Flo Steinberg’s 1975 Big Apple Comix.)

He was in the process of separating from his first wife, Tatjana, and often worked and slept in his small two-room studio a block away from their West 70s apartment. Juggling jobs — and temporarily minus his regular assistant, Ralph Reese — he faced a sudden, two-week deadline on a Jungle Jim comic book. Nothing had been done. His solution to the problem began, I learned, with me. I was to write three Jungle Jim stories in two days, he told me. Then, in 15 minutes, he outlined how to do it. I have never encountered a more basic and lucid explanation of writing/designing comics, and I paraphrase it here for the benefit of those curious about Wood’s methods:

(a) Work with pencil on 8 1/2” x 11” typing paper (to approximate the size of a comic book page).

(b) Conceive a main visual or peak action for each page. Then write the rest of the page around it. In layouts, this visual could dominate the page.

(c) Forget about tricky layouts — since the most important aspect of comics is the story within the panels. Work with the four or five simplest arrangements of panels on a page.

(d) Begin page one in the middle of a situation or action scene. Lengthy establishing material or a deep-background opening will impede the reader.

(e) Write finished dialogue and position exactly (to guide the letterer) in relation to the characters.

(f) Since comics are storytelling-in-pictures, few or no captions are actually necessary.

(g) Work as rough as possible to expedite the writing. This could be so rough that even a circle can be used to represent a character.

Following this “no frills” comics guide, I was able to meet Wood’s deadline. But they were terrible stories. With no time to research the original Alex Raymond characters, and no time to even think, I had resorted to a sort of semi-parody based on half-buried memories of the early ’50s, Johnny Weissmuller Jungle Jim film series. And I also broke one of Wood’s rules — wasting valuable time by executing the pages in extremely tight roughs. To my surprise, Wood made only a few changes, eliminating the more obvious satire in certain lines of dialogue, and then he immediately sent them to the letterer. A few nights later I learned why Wood had expressed little concern about the tight deadline: Artists from all over the city converged on his two tiny rooms. Someone sat in every available inch. In one corner Roger Brand was penciling a story. As he completed pages, they were passed to Dom Sileo and other inkers — who were adding finishing touches to the stories penciled by Tom Palmer and Steve Ditko. Wood, at his drawing table, meticulously inked faces for a while, and eventually vanished. He returned shortly with Tatjana, grinning as he showed her the white heat of activity, leading her into that maelstrom of flying brushes.

It was an exhilarating evening, one that Wood obviously enjoyed manipulating as much as I enjoyed seeing panel after panel of mine coming to life exactly as I had designed them. And — true to the pattern I was just beginning to observe — it was doomed. He called me one night: “Bhob, looks like we’re out of a job.” King Comics decide to withdraw from comic books, passed the finished art and a lone undrawn story on to Charlton … and that was that: no chance to even try to escalate the quality of the stories. The fact that we had all worked our asses off, late into the Broadway night, meant nothing in the business Scheme of Things. Wood’s cynicism about the field he worked in was not only understandable, but contagious. In the weeks that followed, I heard tale after terror tale of each cul-de-sac in his career, all delivered in a sardonic monotone.

His 1967 Bucky Ruckus strip, Bucky’s Christmas Caper, ranks alongside Pogo as the finest humor-strip brushwork ever done, but the deal had a Catch-22: It ran as a Christmas strip, and the syndicate promised to continue it after December if it could pick up a certain number of newspapers. The catch was that the number they named was a figure impossible for any strip to achieve in only a few weeks.

His 1967 Bucky Ruckus strip, Bucky’s Christmas Caper, ranks alongside Pogo as the finest humor-strip brushwork ever done, but the deal had a Catch-22: It ran as a Christmas strip, and the syndicate promised to continue it after December if it could pick up a certain number of newspapers. The catch was that the number they named was a figure impossible for any strip to achieve in only a few weeks.

Wood was the Master Cartoonist — but something was wrong. Potential work was elusive, sliding through his fingers like grains of sand. What Wood hoped to do was divorce himself totally from the commercial comics markets, but barricades were everywhere. Pipsqueak Papers was submitted to Evergreen Review. Reject. Samples were prepared to sell Nabisco on Topps-like humor inserts, and Woody left that day in uncharacteristic suit and tie. No sale. The 16-page Wallace Wood Portfolio, displaying a diversity of styles and printed in the witzend format, was mailed with much anticipation to, as he put it, “every art director in New York.”

“How much work did that printed portfolio bring in?” I asked some months after I had exited the Wood Studio.

“About one or two jobs.”

Still, there were art directors outside the comics field who had grown up admiring Wood work. When certain jobs arose, they phoned him. “I’m trapped by my style,” he said once, referring to the length of time he felt was necessary in completing a page. But his identification with comics was so total and his style so much in that vein, that even his non-comics assignments fell into the comics category — such as the time the agency handling the New York Times Magazine London Fog raincoat ads decided to switch one week from thriller/mystery-type atmospheric photographs to a comics page. A rough was sent over. He handed it to me and stretched out on the sofa to sleep. I worked furiously, attempting to pencil the entire page before he woke up. I waited for the verdict. “Now that’s the way I like a job to look,” he mumbled — his way of noting that my penciling had progressed. Then he carried the page into the next room and began inking. By this time so many work plans had gone awry that I somehow believed the ad was eventually killed by the agency, and never appeared. Years later, I learned from Wood that it did appear, but to this day I have never seen the published ad.

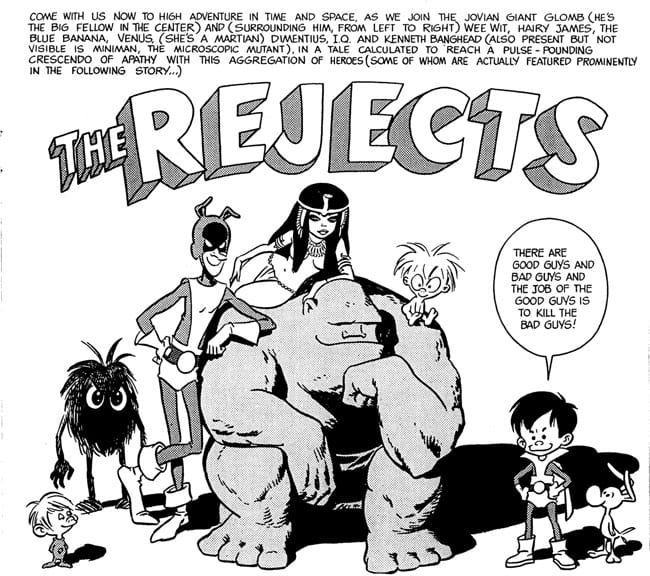

A half-hour animated TV series, with a science-fiction humor concept, held the most promise. At that time, such a show would have been unique, and his juxtaposition of diverse, bizarre, funny characters made the idea appealing. Paramount was interested. After I penciled the presentation from Wood’s character sketches, Wood inked and delivered. And Paramount chose that same month to close down its cartoon studio (Dec. 1, 1967): end of brilliance.

Wood was immediately suspicious, believing that Ralph Bakshi, who had headed the Paramount cartoon studio, was secretly selling the Wood concept elsewhere. “We have to copyright the characters, Bhob, so write a story that includes all the characters, and we’ll publish it in witzend.” I wrote and designed a three-pager, “The Rejects” (witzend #4), and Wood, before sending it to the letterer, made two changes. He eliminated a complicated, labored pun on a line from the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life,” and added, in the splash, a simple, wonderful phrase spoken by the lead character, I.Q., directly to the reader: “There are Good Guys and Bad Guys and the job of the Good Guys is to kill the Bad Guys!”

Wood was enamored of such mirth-maxims and philosophical-aphorisms. He devised or recalled them constantly, proclaiming them (in his near-whisper) as he worked at the drawing table. But his “Good Guys” line struck me then, and still does, as multileveled: On the surface it is a satirical reduction of a basic premise in genre fiction. It served as an insightful self-commentary on Wood’s own encounters and conflicts with art directors — and it also stands as Wood’s summation of the true nature of life on Earth.

There were the rejects and there was Topps. Ah, Topps was faithful, sending over huge batches of gag-sheets to be cartooned. And while the whirl of Wood’s electric eraser expressed his dissatisfaction with my inking, he was pleased with the way I designed and roughed these gags.

Like many artists, his commercial work and his “real” work fell into separate categories. Wood’s reliance on assistants freed him from thinking about the work he did for money. If roughs and penciled art were put in front of him, fine — he could ink them automatically, and his mind was free to fantasize and plan his own personal creations, his “real” work. But the distinctions between the two categories seemed to blur somehow. Often it seemed that Wood had assistants for no other reason than to escape the isolation of the work and to act as sounding boards for his continual flow of ideas, fantasies, future projects — and problems. Conversations at many art studios dwell on business transactions, but at the Wood Studio talk more often ranged over psychological transactions, an interest that surfaced in his work.

The studio atmosphere was akin to group therapy. Dom Sileo, between jobs at Harvey Comics and then inking regularly at the Wood Studio, was disturbed by these introspective interludes; and once, when Woody was not present, he asked me, “Why does he have to tell us all that?” The studio was often like a Grand Central of artists. They came and went. One night, Augie Scotto arrived. Scotto had worked on 1949-53 Western and crime comics before settling in as an artist on Will Eisner’s PS magazine for many years. We were working our way through a pile of Topps’ Travel Posters, and Scotto was there to assist for a few hours. I was in the back room, and Woody appeared at the door with a big grin. “Bhob, come watch this.” Scotto sat down at a board while Woody, Dom and I looked on. He clicked the snaps on his briefcase, pulled out a brush and dipped it in the ink. Silence. Then, with a single deft stroke, Scotto moved his hand across the paper. He lifted the brush, leaving a 14” long, perfectly straight line on the paper. It played like a magic trick, but it was for real. Woody then went back to work, still grinning.

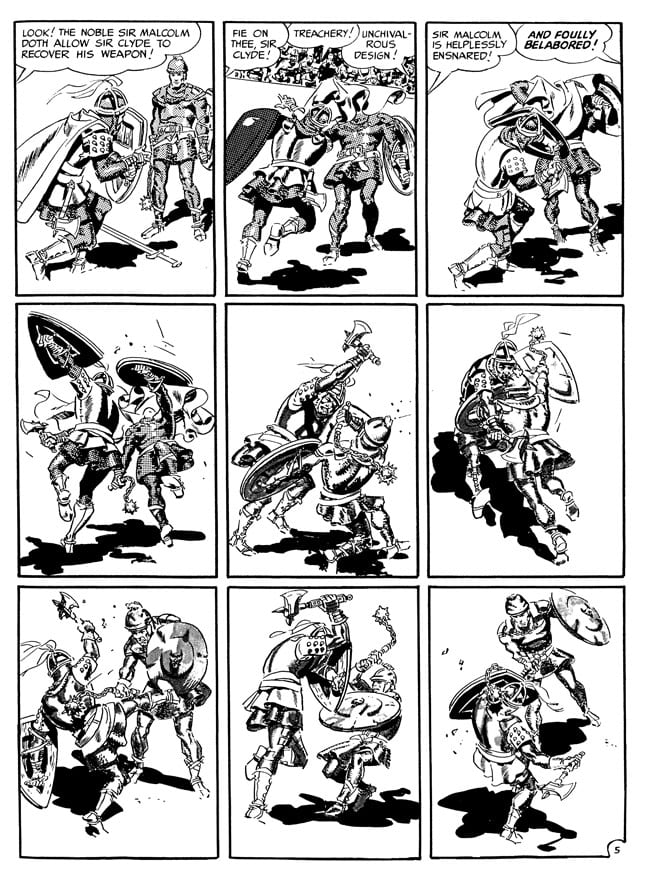

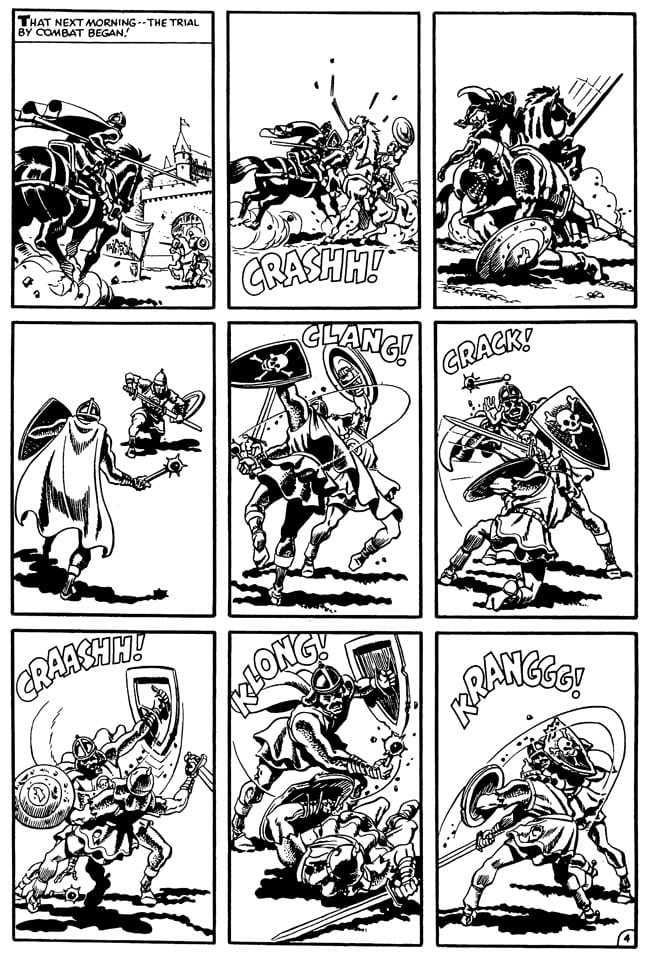

On another occasion, he was grinning his Woody grin and chuckling his Woody chuckle when, without any prior discussion, he pulled open a suspension file and hauled out tearsheets of “Ivan’s-Woe,” Howard Nostrand’s parody of Wood’s “Trial by Arms” (Two-Fisted Tales #34). Nostrand, for some reason, had the notion that Wood was not happy about “Ivan’s-Woe”; but my memory is that Woody was flattered and pleased by the homage—obvious not only in the art, but in the opening line, which had with bold italics emphasizing Wood’s name: “Yield now, Sir Knight! Thy lance will be but kindling wood beside my own!”

When Woody introduced me to Wayne Howard in 1967, it was pretty clear that he was impressed by the 18-year-old’s Wood-like reflected highlights, and other brush effects. During his senior year of high school, Wayne Howard had won the National Scholastic Press Association’s Best Student Cartoonist Award and, throughout the late ’60s and early ’70s, he continued to use Woodwork as a model while he whipped out pages for Marvel, DC and Charlton. Wood was fascinated by the efforts of Howard and the other artists who emulated him. And the closer they got, the more intrigued he became. So, naturally, he was still somewhat amazed, 13 years later, by the work that went into Nostrand’s “Ivan’s-Woe.” He knew that it was work, not any kind of a rip-off, and he perceived that it was a genuine homage, not a mockery.

I remember standing in the center of the Wood Studio as he handed me the torn Witches Tales page of Nostrand’s nine-panel, pantomime joust-and-mace combat. I remember him standing behind my right shoulder, pointing at the panels, indicating how Nostrand had duplicated the “Trial by Arms” layout and the story situation carrying the combatants from horses to the ground. And mainly I remember his delight at the fact that Nostrand had not copied the combat sequence, but had redrawn all the figures (with two or three exceptions) into completely new poses, setting up totally different angles, yet still maintaining a faithful simulation of the Wood look. And I also remember that at that moment I asked the only logical question.

“Did you ever meet Nostrand?”

“No.”

No? I was dumbfounded. Perhaps I had naïvely thought such a pastiche and the mutual respect of these two men would have brought them together. Surely in 13 years? But no: never. They had only met on paper. I left Wood’s studio thinking that Nostrand had picked, even if unconsciously, an apt metaphor: the two combatants could have been Wood and Nostrand jousting it out (“KLONG! CLANG! CRACK!”) with brushes and egos instead of lances and mace.

Having already established witzend as a forerunner to the underground comics, Woody now wanted to do something grandiose. He had launched witzend in the summer of 1966 — the same summer that I had coined the term “underground comics” while on a panel with Ted White and Archie Goodwin at an early comics convention. “Do you mean fanzines, Bhob?” asked Ted. I drew a parallel with the underground film movement, and predicted the birth of a new form. Since there were no such things as underground comics then, only a few people present — Paul Krassner, Art Spiegelman and Wood — grasped what I was talking about.

The arrival of the undergrounds confirmed for Wood that his notion of a magazine that offered artists a forum for personal expression had been on target. And in 1968, when the undergrounds were aborning, he was ready to throw himself into a project that would outdo his previous work for witzend. But what? One night, while Dom inked in the next room, Woody sat on the sofa and outlined it to me — a Tolkienesque, Arthurian saga of great complexity, which he wanted me to write. (According to his Woodwork Gazette #1, he had actually been formulating this material since the age of 10, when he had called it King of the World.) I took notes at a mad pace, but no sooner did I get one of his plot thoughts down than he would backtrack, interrupting with a different approach or restructuring. I left, notes in confusion, and returned the next night, empty-handed. “The problem here,” I said, “is that you have so many ideas that it’s just a matter of getting it down in the sequence you want — which I can’t figure out and can’t do. I can’t catch up with you. And whatever I come up with, you’re almost certain to change — since this is your story and you feel so strongly about it. The solution is you’ve got to write this yourself. I really don’t think you’ll ever get what you want any other way.” He stared at me, listening, neither agreeing nor disagreeing, and a few minutes later we had moved on to another subject. My statement was somewhat in the nature of a challenge, but there were other things I did not say. By this time I had become disillusioned to a degree by what I considered Wood’s own misdirection of his talents.

During the next few days, Wood spent little time in the studio. Then, at the end of the week, he reappeared, clutching a stack of paper. He was excited. “I’ve got it,” he said enthusiastically, handing me the stack. “It’s all there, Bhob.” This was only a handful of notes, plot fragments, ideas, long lists of character names — but, yes, it was all there, and, as he talked out the interweaving plotline, I saw he now had the beginning for a work of scope and ambition. “I intend to be working on this for the rest of my life, Bhob.” He called it The World of the Wizard King, and it appeared originally in witzend with appropriately rough-hewn illustrations accompanying chapters in a written text form. Because this suggested a typeset illustrated novel rather than comics, I later attempted to agent the early witzend version to the first publishers of Tolkien in this country, Houghton-Mifflin. The Houghton-Mifflin editor who rejected it called it “pornography.”

Shortly after beginning Wizard King, he also negotiated the Military News strips that eventually developed into his Overseas Weekly comics sections—and a regular money flow. Both areas, personal and commercial, were suddenly nailed down. It all looked promising and secure, and turning witzend over to Bill Pearson freed him from licking stamps and the other time-consuming chores of small-press publishing. Simultaneously, I had my own breakthrough, as the Topps roughs led Topps to offer me a job — probably on Wood’s recommendation. If so, he never mentioned it. I didn’t see him as much then, although I dropped by the studio occasionally. Ralph Reese had returned. Reese was the ideal assistant, since he fit into Wood’s scheme of total perfection: Reese’s pencil art, although it did not look like Wood art, had every line and detail precisely placed for Wood’s brush. One week, they faced a curious task. Howie Post, having just sold his Dropouts strip, had turned in to DC an unfinished Anthro book, and it was passed on to Wood. But Post had not actually penciled the book — every panel was a very loose rough. Wood, undaunted, began inking. It was like the old joke: “He’s so sure of himself he does crossword puzzles with a pen.” But it wasn’t a joke; it was just a way of getting the work done faster. Wood was inking lines that weren’t there — he was drawing with the brush.

He knew that I had worked as a staff editor at TV Guide, and shortly after his full-color TV Guide illustration appeared (March 23, 1968), he asked me if I was somehow responsible for the assignment. Since the picture, showing animated superheroes chasing funny animals, was a surprise to me, I immediately said no. But it’s possible this was not exactly the correct answer; I’m not sure. Years later, pulling together my memories of Woody, I thought about this question and suddenly remembered that one day in 1966, with a brief moment to spare, I had dashed off an inter-office memo to one of the magazine’s senior editors recommending Wood as a possible illustrator.

By 1968, a friendship had developed between Woody and myself, one that had a somewhat frightening foundation — each of us had perceived the other’s seeds of self-destruction. We remained wary, even as we became more open and honest with each other. Further, although neither of us knew it, because we never discussed it, there were several striking parallels in our family backgrounds.

I had taken to walking in Central Park regularly. One day early that summer, when he did not seem busy, I suggested he join me and I saw an odd confusion flash momentarily across his face. Reluctantly, he agreed, and we walked the few blocks to the park. Woody squinted in the sunlight, appearing curiously out of place and uncomfortable there, as if anxious to return to his natural habitat of smoke-filled room with ink-stained drawing board.

Later that year, he turned up at Topps, arriving during the lunch hour when the Product Development offices were empty. I was there working alone, and he came into my cubicle. He seemed detached and depressed. Dressed in wrinkled, baggy clothes, it wasn’t clear to me whether he was picking up a Topps job, simply visiting, or what. I offered him a chair, but instead he settled down on the floor and began eating out of a brown paper bag. It was, I thought to myself, a reversal of the way he had looked the day he had neatly set out to conquer Nabisco. He mentioned that he had only been to Topps twice in eight years, which I found odd, considering the overwhelming amount of work he had done for this company. (I was constantly finding older printed work of his in the Topps metal file drawers.) I was struck by a certain irony: here was a man, at that moment strangely giving the appearance of being only one step removed from a street bum, whose artwork had helped write the paychecks for the well-dressed people throughout the building. I had to know how he felt about walking into companies that had profited for years from his talents. His answer was what I expected: he felt exploited and used, and he expressed this in a sudden rush of deep bitterness. A short time later, the others returned to the office from lunch, and I studied their faces as they talked with their star cartoonist, crumpled in a sad heap on the floor.

In 1970, he remarried and lived with his second wife, Marilyn, in Woodmere, Long Island, with the Wood Studio of the early ’70s located in nearby Valley Stream. After The EC Horror Library of the 1950s (Nostalgia Press) was published in 1971, Wood felt that my choice of stories had overlooked his early EC horror work. My article in this book resulted in various phone calls from editors, who tracked me down through Nostalgia Press. Monster Times wanted to reprint the article; I refused, so they wrote their own — while plagiarizing my last paragraph. A small-press literary publication, Shantih, asked me to write a brief history of EC; instead, I mailed them a short piece about visiting Wood’s Valley Stream studio, titled “His World,” which Shantih reluctantly published. I mailed Wood a copy and received the following cryptic postcard:

Thanx for the mag. Very literary, impressive, and your article on me was quite genuinely artistic, touching and apt. You have a knack. I wouldn’t change a word of it for anything, so don’t worry. Nothing new here, nothing ever changes. Am seeing a shrink again, so maybe in a year or so I’ll be able to do something, I don’t know what. Keep in touch.

At a Manhattan studio with Ron Whyte, screenwriter of MGM’s Sidelong Glances of a Pigeon Kicker (1970, starring Jordan Christopher), prospects were on the upswing for Wood. I wrote him a long letter analyzing and praising his unusual fantasy story, “The Curse” (Vampirella #9), and he wrote back:

You are an incurable fan, but I forgive you. Thank you for the kind words about my recent stuff. You apparently missed the Big One, though. I personally thought a little epic I did called “Of Swords and Sorcery” for Marvel was the best thing I’ve done in years. Some PhD-to-be wrote asking for the originals on “Flight into Fear” as he was including it in his thesis on the effect of Russian folk tales on contemporary literature, and had all sorts of proof that I must have been familiar with one particular series of legends of a spooky, skeletal wizard character, and pointed out a dozen points in the story which were practically identical with the folk tales. I was tempted to go along with him and confess that I’d swiped the whole thing from Russian Folks, but honesty prevailed, and I suggested the racial unconscious as a possible explanation. And I wasn’t entirely kidding. My most recent theory is that instinct is racial memory, cellular memory, if you will. And I think it’s almost proven by some experiments I’ve seen done with animals.

Anyway, you are right — to a point. This was a very happy and productive period, and I was starting to give them the Real Stuff, as much as the Code would allow, anyway ... and then they went into reprints!

I must admit that I was somewhat offended that they didn’t give me Conan. But now I’m glad. I did a Conan-type character for Warren and will have the satisfaction of knowing that they (He — Stan Lee) will feel a pang when they see it. But enough of this chit-chat.

Do you know I almost did my own mag for Warren? I had a %, a salary, and all the freedom I could want — and I quit, just as the artists were getting to work on the stories. “Why?” you ask. “Because the first week I was on salary, I didn’t get it,” I reply, simply. Since then I’ve approached such diverse people as Bill Gaines and Al Capp with the idea — no results so far, and meanwhile have lost interest in publishing. It costs (at the very least) $120,000 to start a magazine. You could produce a movie for less than that! So now I’m busily conning people I know who are in the movie business. Did you ever hear of Tom Scheuer, Ron Whyte, Pablo Ferro, Ralph Bakshi, Steve Krantz or Jordan Christopher? These are my contacts with the TV-movie scene, and I have an agent — a literary agent, who is now reading my scripts for the Warren project. Two of them are very adult and would make good feature films. Also two art agents who handle such people as Mort Drucker — and a lawyer, Ron’s lawyer, and I’m all set to go. HERE’S MY PLAN …I still want to do a book — a BOOK now, not a magazine, but first I want to make a bundle of money. And I just might. Right now I’m working on creating and designing the characters for a new TV kiddie show for Bakshi/Krantz. Do you know they’re doing a full-length feature film of Fritz the Cat? (I only heard about it a week ago and saw some of the drawings yesterday.) And if that goes — and it should — I want to be in on the NEXT one — The Wizard King or Pipsqueak Papers or even Betty Boop Freaks Out, Tillie and Mac or Casper the Friendly Ghost Gets Horny!

By the way, I can’t/won’t take an interest in Lord of the Rings. A couple of other people also saw me illustrating it, doing a comic book version or a film — but believe me, IT WILL NOT TRANSLATE into any other medium. It would be a dull book and either a long, stupid, boring movie, or a short, meaningless one. I really think there are some things that are meant for just one form (EC short stories, Alice in Wonderland, Poe — and Tolkien). But that’s not to say that his World, this strange CATEGORY he’s either created or revived, need be neglected. I’m doing The Wizard King over — in comic strip form. It was to be my big contribution to my magazine, and someday may be my BOOK — and at last I’m happy with it! Each time I do it, it gets better. And since quitting Warren, I’ve looked it over and feel the need to revise it some more. I’ll have to cut pages apart and add some panels and a couple of pages to the beginning, etc.

A lot of stuff has been happening meanwhile, mostly bad. I tried to work at home for a year. Couldn’t. My wife was pregnant — did I tell you? — but had a miscarriage. I wrecked our car. My wife and mother had a fight and are mortal enemies. I’m deeper in debt than ever, behind on my taxes, behind on my alimony, Marvel and National have been fucking me around something fierce for months, and Topps has apparently fallen apart. I saw one of their old guys (an Irishman, Kelly or something) up at Krantz. But now I have a studio in town (at Ron’s), an agency that gives me spots, went back to Mad! (Would you believe it?), did a couple of ad jobs, a comic for Peter Max’s mag — did you see it? And all in all, things are looking better than they have for a few years. What are you doing? If you told me, I’ve forgotten. How’s Boston? Almost went there; applied for a job with Al Capp — haven’t heard. Write soon and often.

Love, Woody

Obviously, he had forgotten that I had been working for him during his initial contact with Ralph Bakshi, and the “Kelly” he refers to was actually Larry Riley, former Fleischer/Paramount animator, comic book artist in the late ’30s and mid-’40s, mastermind of the Harvey Comics 3-D process, third- billed animator on Fritz the Cat, creator of numerous Topps gimcracks and the artist behind many of the animated cartoon light signs displayed during the ’70s in Times Square. The Pablo Ferro he mentions is of the ’70s ad agency, Ferro, Mogubgub & Schwartz, and can be seen acting in Robert Downey’s Greaser’s Palace (1972). During this period, Ferro shot some 40 hours of videotapes documenting Wood’s life by following his subject everywhere, including the 1972 EC convention. Wood, by the way, did work on a feature film — in the ’50s — when he storyboarded the live-action Weddings and Babies (1958) for Morris Engel, but very few people saw this critically praised autobiographical drama (about the life of a commercial photographer) because Engel, displeased with the distribution deal he was offered, shelved it.

In his next letter, mailed from his 998 East Broadway address in Woodmere, he finally responded to my comments on “The Curse”:

Thanks for your letters and all the nice things you had to say about my stories. I kind of liked them myself, and they bore out my theory, which is that anything that’s fun to do is fun for the reader — or audience, or whatever.

Just finished up with/for Jim Warren. Turned in my own job a couple of days ago, and the last jobs should be in next week. And that’s it — but don’t tell anyone — yet! I may send you a copy of the letter I’m going to write him after everyone’s been paid. He may sue me for libel and slander, but I am not only going to quit, I’m going to fix it so no one will ever work for him again. But I hope he comes out with the issue. That was why I stuck it through. It would be a shame if he just shelved the whole thing, as there is some great stuff in it. Also I’d like to have it as a sample, in case I try again. Well, anyway, I have photostats and advised everyone else to get stats made just in case.

Just dug out your letters. In the last one you said it was fantastic I could summon up such enthusiasm no matter what I’m up against. You have no idea. I’m looking around, wondering what next. Maybe I should get out of this business. Am going to talk to a friend about trying something else next week. And I’m fresh out of enthusiasm.

It would be nice, I think, to do something else for a living and just dabble occasionally, whenever I feel the urge or have an idea — and be able to donate it to a fanzine or the underground. But where can I make anywhere near the same money? This friend, Joe Newman, is a production man and printing buyer. He says there’s a boom in the production business (he’s in Conn.) and I should think about organizing a studio to service printers with ready-to-shoot pages. Hmm … well, we’ll see.

I was amazed, amused, flattered and delighted at your comprehensive critique of “The Curse.” And guess what … I drew it first and didn’t know how it was going to end when I started! It’s the only way. You’re not married to some simple-minded plot and better ideas keep occurring as you go.

Did you read my other stories — like “Cosmic All”? I was rather pleased with that — in a different way. It’s not that new an idea. I just feel I did it right.

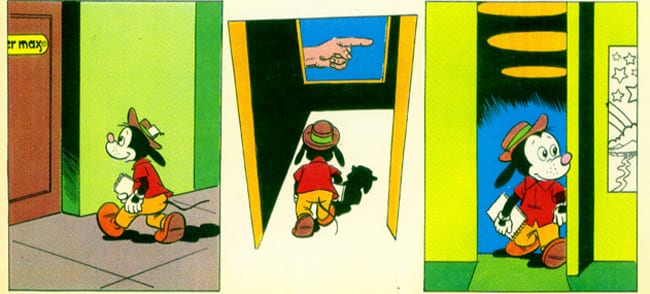

By the way, the Max job was originally “Mickey Mouse Meets Peter Max” (he chickened out), and it was the “Yensid” studios. Only a nut like you would worry that one around until you figured it out.

The racial memory/instinct theory: They took a bunch of baby ducks that had never been allowed to see anything since they were hatched. They put them in a box that was open on top and flew objects over them. The ducks did not react to a cross shape like this ( — + — ) with the long arm pointing in the direction of flight, but when they turned it so the long arm was like the wing spread, the ducks went into a panic and tried to find a place to hide. Now, to me, that’s memory! And since they had no first-hand experience, it had to be inherited memory. There was more, but I forget. Anyway, it explains some things, like why the offspring of domestic animals and pets aren’t afraid of people, why birds migrate to the same place, salmon swim upstream, etc. And it follows that people have sets of these memory-instincts too. (Freud thought so.) Did you read The Naked Ape? One of the most fascinating books I’ve ever read!

Some day I will tell you about the great Moon Landing Hoax. (It was all done in a Hollywood soundstage.) Write soon and often. Keep well. Be happy.

Woody

I wish I had written to him more often because I was unaware of the turns Wood was taking. After a couple of years of staff work at Topps, I had left, but continued to freelance Wacky Packages and other gags. At one point in the early ’70s, I returned to Brooklyn to work temporarily at Topps. One Friday afternoon at five, I had the urge to phone Woody, who was then doing his Overseas Weekly pages in Brooklyn at a studio near Prospect Park. He sounded strange and muffled over the phone, demanding that I get a cab and come over. I did. His two rooms were a mess, and he was alone, wildly drunk.

“How long have you been drinking?”

“Three … three … ” I could hardly hear him.

“Three hours?”

“Three days.”

I attempted to talk about his unfinished Overseas Weekly work on the drawing table, but he was uninterested. Since I was unaware of the exact events that had brought him to this point, communication was difficult. But it had been so long since I had seen him that I didn’t really want to leave. Then I noticed the hatchet leaning against the wall near the front door.

“Why do you have the hatchet?”

“This is one of the worst sections of Brooklyn, Bhob. You’ve got to be ready for anything.” He whirled into the bedroom and returned carrying nunchaku sticks, the martial arts weapon made of two rectangular blocks of wood joined by a short cable. He sat down.

“I take these when I go out. They’re illegal on the street … so … so I put them in my back pocket like this” — he demonstrated, staggering as he stood up — “see, and then I wear my shirt over them like this, see, and I walk along, and … and nobody knows. I’m ready for them.” He grinned and dropped the blocks on the floor.

An hour later, the arrival of Larry Hama, skilled in martial arts, prompted Woody to give a demonstration. Handling the blocks, even when sober, takes a good deal of practice. Woody placed one of the sticks under his armpit to execute the strike maneuver, but his repeated efforts to jerk it forward and out were unsuccessful. Instead, the stick dropped limply to his hip each time. Then, suddenly, he launched an attack on the doorframe at the entrance to his bedroom, smashing the blocks into the wood again and again. As he continued to flail the blocks in a wild fury, sending paint chips scattering across the floor, I saw for the first time the depths of his anger and pain, expressed in an animalistic rage. It was painful to watch. Finally, he stood, exhausted, breathing heavily, and Larry attempted to direct his attention to the drawing board. “What’s the deadline on this?”

“Um … Monday.” The amount of remaining work was considerable. It seemed obvious he was going to miss the deadline.

“Well, look,” said Larry. “I’m going to leave now, but I’ll be back.”

“What?”

“Listen, get some sleep. I’ll start to work on these pages in the morning, and we’ll finish them this weekend.” Larry and I left together at twilight — with Wood insisting that I stay. But my father was an alcoholic, and I have little patience with violent, heavy-drinking scenes — my feeling simply being that during my childhood I had no choice, lived through such episodes, survived, and now I had a choice.

Larry and I headed for the subway. And I was left with the impression that Larry and Ralph had both grown accustomed to such situations. The truth, I learned later, was that Wood rarely ever missed a deadline because of drinking.

The next time I saw Wood in the mid-’70s, he had moved again to a tiny room on, I believe, West End Avenue. His studios seemed to get progressively smaller. This one was, in fact, one of the smallest apartments I had ever seen in Manhattan — with space only for a bed and a cramped work area; the kitchen was dwarfed to such a degree that only one person could stand in it. But it was clean, neat, well kept, and Wood was sober, busily at work on a page — minus assistants — and making plans for the publication of Wizard King in France. I was happy to see that he had, evidently, straightened out completely. Shortly after this visit, he moved to Connecticut, launching what he referred to as his “publishing empire” and “fan club” — his plan to gain total control over his own work. In a brochure he promised, “The first chapter of The Wizard King will be published soon in France and will probably be serialized in Heavy Metal.”

But negotiations over money brought Wood and Heavy Metal to a deadlock, and The Wizard King never appeared in the magazine. The correspondence I received from him in the late ’70s is almost solely concerned with his own publishing plans, and one letter ends, “Write soon and tell me what you think of my get-rich-quick scheme. I can’t wait to tell Heavy Metal to go fuck themselves!”

Nevertheless, he continued to work on commercial comics and other outside jobs until 1978, when a stroke caused a loss of vision in one eye. That same year, he married Muriel Van Sweringin. By this time he had made good on his publishing promises — issuing collections of Cannon and Sally Forth, while establishing a direct rapport with his audience through The Woodwork Gazette.

To write a memoir, one must remember. But for Wood’s friends there are unpleasant memories that weave in a frenzied dance throughout the pleasant memories. Shortly before I arrived for a visit, I heard the tale of an incident that foreshadowed Wood’s end. His house hung, precipice-like, over the highway, and Wood’s studio was a drafty shed separated from the house. On an extended bout with booze, he had locked himself in the shed and later emerged bleeding — his head split open. Bill Pearson and Muriel managed to get him to a hospital, despite his protests, and stitched up. But what happened inside the shed? No one, including Wood, knew exactly. Had he been rigging his axe above? If so, what was the intent? Or had he simply fallen? It remained a mystery.

He looked, I noted, about 10 years older than his true age. But Muriel and Woody seemed happy together, and they entertained me by performing duets of songs from the planned Wally Wood Sings record album. The three of us watched an HBO show together. Instead of alcohol, he drank one cup of tea after another. And he was much more eager to talk about future plans than past injustices. When I asked what had happened at Heavy Metal he said, “Fuck Heavy Metal,” and changed the subject.

Wood — like a number of comics professionals — loved guns, was fascinated by their power and meaning, and relished sessions on the target range. In the shed studio, one was mounted on the wall. “That can blow the head off an elephant,” he said. He reached into a metal file drawer, pulled out a Magnum and handed it to me, saying, “That’s the same one Clint Eastwood used in Dirty Harry.”

Paranoia, William Burroughs said, is simply having all the facts. I recalled the events that had led to my writing “The Rejects,” and told Woody how startled I had been to see that Bakshi’s Wizards (1977) resembled an animated witzend with characters strongly derivative of both Wizard King and Vaughn Bodé’s “Cobalt 60” (witzend #7). This was also noted in Hank Luttrell’s film review for the Milwaukee American Bugle; Luttrell wrote that Wizards “swipes” from Wood, Bodé and others. In the film, a wizard shouts “Morrowkrenkelfrazetta” as a magical incantation, but no “Woodbodé” incantation is heard. The Wizards-like drawings in Woodwork Gazette #1 are listed in Wood’s checklist as “Wee Hawk — presentation for proposed Paramount TV show.” The name of a lead character in Wizards is Weehawk. But I discovered during this visit that Wood had given little thought to Bakshi’s film. When I brought up the matter he expressed little interest. Perhaps he did not see the film until later. In 1980, he told Shel Dorf, “I tried to sell several Saturday-morning shows to TV, but all that happened was that they wound up stealing one of my characters and using it in Wizards.”

Woody’s Connecticut house was a friendly, rambling structure, comfortable and large, and it was nice to see him settled in such a place, so different from the tight Manhattan quarters. I was offered one cup of tea after another, and when I went upstairs to sleep, it kept me awake. In the middle of the night I wandered downstairs through the darkened house to find the bathroom, and saw him moving about in the unlit kitchen, the Wizard King himself, silhouetted against the window, keeping his nightly vigil.

In 1980 he took off again, relocating in Syracuse to supervise the publication of his work there. Someone described his Syracuse apartment as “living in squalor,” and here Wood sat, surrounded on all sides by Woodwork, his life in art spread on the floor about him, and, yes, the knowledge that he had total control over it all: King of the World.

In August 1981, he moved to L.A., and he told those close to him what he intended to do instead of being plugged into a machine. And he designated when he intended to do it. There was the gun and there was the deadline. He kept his word and met the deadline, exactly to the day.

Beyond the Woodwork is the Wood influence, evident when one spots that desire for perfection in the lines of Ralph Reese, Dan Adkins, Paul Kirchner and others who passed through Wood’s Master Class. And then there is the Woodwork, the “real” work that he had struggled to produce as his own personal expression. Wood lived to work, to create the Woodwork. And he did so obsessively, on and on into the night — night after night, month after month, year after year — until the prospect of doing no work loomed before him. There were Good Guys and Bad Guys inside Wallace Wood. The Good Guys forged ahead on the work, taking incredible risks, getting the work done. The Bad Guys tried to stop the Good Guys. There were Good Guys and Bad Guys, and the job of the Good Guys was to kill the Bad Guys.

All Wallace Wood art ©Executor of Wallace Wood Estate, all other art ©its respective copyright holder.