Cowboy cartoonist and Western novelist Stan Lynde died of cancer in Helena, Montana on August 6. He was two months shy of his 82nd birthday.

Most obits credit Lynde with producing two syndicated comic strips—Rick O’Shay, May 19, 1958 - May 7, 1977; and Latigo, June 25, 1979 - May 7, 1983. Beyond syndication, he also did two graphic novels and one panel cartoon, plus a daily comic strip he did while in the Navy, 1951-55. But he actually did three syndicated comic strips: unique in the history of the funnies, Rick O’Shay counts as two. Midway through its run, Lynde changed the strip from a satirical, mock Western drawn in an approximately big-foot style to a saga of the Old West rendered realistically.

“At first,” Lynde said when I interviewed him in 1992, “the strip was something of an anachronism. It dealt with the twentieth century intruding upon this sleepy little Montana town. But the readers tended to want their West to be the Old West. And I kept hearing that, and finally, I thought to myself, that’s what I want too. So in the late sixties I adopted a centennial theme: if it was 1969, it was 1869 in the strip. And I kept that going. Once we were in the Old West,” he continued, “I felt I had to be authentic about it. Charlie Russell sort of set the standard.”

Montana’s Charles M. Russell, the cowboy artist, is celebrated for the fidelity of his portraits of the Old West. “Painters of the West today are locked into doing it very authentically;” Lynde said, “—you don’t find much successful impressionism of Western subjects.”

Through his art, Russell “has achieved the status of sainthood in Montana," Lynde went on. "No politician can succeed in Montana unless he's for Charlie Russell and against gun control," he added with a grin.

Born September 23, 1931, in Billings, Lynde grew up among cowboys, sheep men and Native Americans on an isolated sheep ranch near Lodge Grass on the Crow Indian reservation. It was there he took up drawing. His mother gave him crayons and paper and taught him to draw. And he drew what he saw—cowboys and horses. And Charlie Russell.

"Like many families growing up in the thirties, my parents were quite poor during that period,” Lynde recalled. “The Depression was in full swing in Montana, and we survived primarily by our garden and my father's rifle. And the only decorations in our house were Russell pictures taken from a calendar and put on the wall, so I grew up looking at Charlie Russell paintings."

“Cowboys were my heroes,” Lynde said during an interview with the Independent Record last December. “I followed them around, and they played with me.”

His parents read him the comics in the Sunday paper. “I thought they were natural wonders like Old Faithful,” he said. “And when I found out people created these magical stories, it was an epiphany—I thought, ‘That’s what I’m going to do.’”

Lynde began drawing cartoons in high school and attended the University of Montana for two years until 1951 when he gave up trying to master a recalcitrant curriculum and joined the Navy, where he created a daily comic strip, Ty Foon, for the five-days-a-week base newspaper on Guam. He loved it so much he extended his tour on the island by six months to continue drawing the strip.

After another two years aboard a submarine tender permanently moored in San Diego, Lynde was discharged in 1955 and went to work briefly as a reporter and artist on a weekly newspaper in Colorado Springs. In January 1956, he set off for New York to try his luck. He wound up working as a typist at the Wall Street Journal until he had the idea for his spoof of Hollywood Westerns.

“I had decided to produce a feature which would satirize the fictional Western, the TV Western, from the standpoint of the authentic West in which I’d grown up, taking the Western conventions and stereotypes of fiction and standing them on their heads. So Rick O’Shay began as a spoof on the synthetic West, or what Gary Cooper used to call ‘easterns in big hats.’”

Rick O’Shay was the mild-mannered marshal in the twentieth century backwater Western town of Conniption, with a colorful population that included a number of other punny-named citizens—gunslinger Hipshot Percussion, banker Mort Gage, a lovely saloon keeper named Gaye Abandon, the kid Quyat Burp, Deuces Wilde the gambler and self-appointed mayor, Doc Basil Matabolism, and General Disability and the troops at nearby Fort Chaos.

Lynde did Rick O’Shay for almost twenty years. It appeared in about 100 newspapers but eventually didn’t earn enough money; his income failing to keep pace with inflation, Lynde found himself losing money and going into debt, and when he couldn’t negotiate better pay, he reluctantly gave up the strip. In 1962, he had returned to Montana, and he pursued other enterprises: he wrote a screenplay and magazine articles, painted and did illustrations and made the rounds of speaking engagements. Then in the spring of 1978, he was approached by another syndicate to create a new strip. Lynde conjured up Latigo, which, he said, “was designed to be an authentic, historically accurate Western.”

Latigo, however, lasted only four years. During that time, Lynde remarried, to Lynda Brown, and when Latigo ceased, he continued a career of miscellaneous writing and drawing, including, in the fall of 1984, a weekly panel cartoon called Grass Roots that he syndicated himself. It ceased in 1985, but Lynde revived it in 1998 for another year. In the late 1980s, Lynde produced a Western humorous comic strip for a Swedish newspaper; it was not published until 1997. In English, its title was Chief Sly Fox; Lynde published some of it in his newsletter, The Cottonwood Clarion, under the title Sly Fox & Company.

In 2002, Lynde returned with another exclusive comic for the Swedes, Bad Bob, about a hopeless wild West criminal. According to Wikipedia, this strip is still running in reprint.

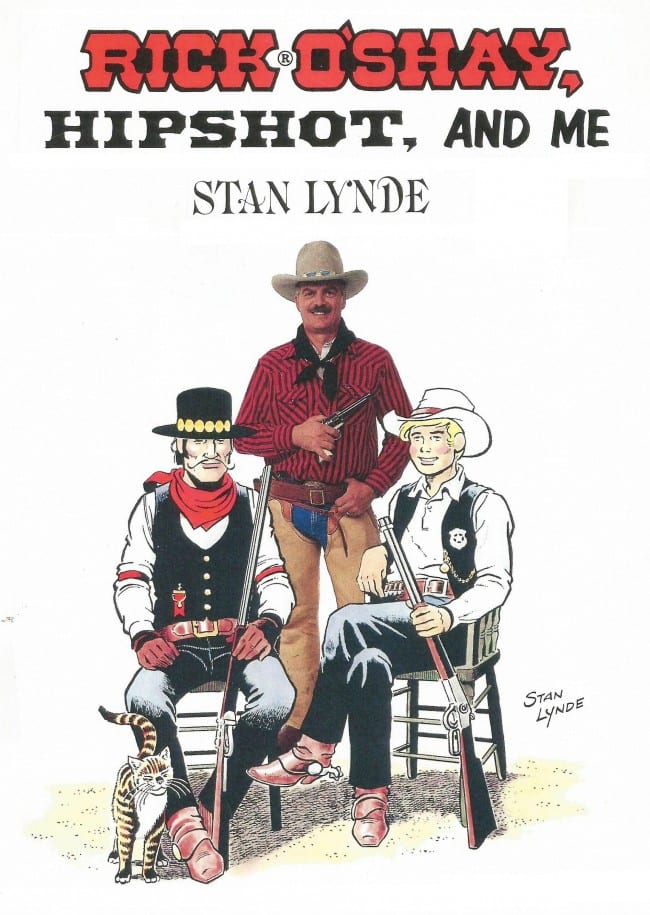

With Lynda (whom he called “the Lady Publisher”), he founded Cottonwood Publishing, chiefly to publish collections of his strips. The first of these, a memoir entitled Rick O’Shay, Hipshot, and Me, appeared in 1990. They also opened a retail store, Stan Lynde’s Old West, in Kalispell, Montana.

The entire run of Latigo has been reprinted but only the first few years of Rick O’Shay because Lynde’s files—original art and syndicate proofs—were destroyed when his home burned in 1990, and scouring legions of Lynde fans for usable clippings took time.

In the early 1990s, Lynde produced two graphic novels: Pardners and The Price of Fame, the latter featuring Hipshot Percussion. And he began writing prose novels about a young 19th century Montanan named Merlin Fanshaw. The first, The Bodacious Kid, was published in 1996; seven more have appeared in this series, and Lynde was working on the ninth. He also wrote and published a historical novel, Vigilante Moon, about corrupt life in the mining town of Bannack, Montana, when it was under the thumb of the notorious Henry Plummer. His novels are distinguished by the authentic-sounding lingo of the characters, who talk just as we imagine the inhabitants of the Old West talked. (Or, at least, the way Charlie Russell portrayed them talking in his book of short stories, Trails Plowed Under, and others.)

Last fall, Lynde decided to move to Ecuador, where he and the Lady Publisher could live comfortably on Social Security income. They donated much of their accumulation of material and memorabilia to the Montana Historical Society until they’d reduced their holdings to whatever could be packed into four suitcases, two backpacks, and a camera bag.

Giving a farewell talk to the Historical Society in December, Lynde called the move the first chapter of a brand new book.

“I feel very blessed,” Lynde told the Independent Record at the time. “I’ve been able to do the work I love for an appreciative audience. I love this state and people of this state. If my tombstone said something about Montana, I’d be really happy. I’ve never met any state with people who have such character.”

The plan was to return to Montana every autumn for a few months, but it didn’t turn out that way. Through the early weeks of January 2013, the Lyndes scouted the Ecuador environs for a place they wanted to live and found Cuenca to be “a perfect fit—a city of rich and diverse cultures, and a blend of the historic and modern,” Lynde wrote in his blog. “We move there and rent a high-rise apartment alongside the Tomebamba River. We travel twelve and a half miles north to the spectacular Cajas National Park. With mountains reaching from 9,000 to 13,000 feet above sea level, ice cold lakes, streams, and waterfalls, roving herds of alpacas and lamas, and abundant wild flowers, we find the Cajas a remarkable and very special place.”

But then in seeking relief from recurring bronchitis, Lynde learned that he had squamous cell lung cancer. Lynde was Born Again about the time he concocted Latigo, and the experience calmed his otherwise raging ego (he said) and yielded a kind of stoicism, maybe even fatalism, useful for dealing with the health crisis.

As he had throughout his life, Lynde looked to Charlie Russell and reported in his blog:

Russell created more than 2,000 paintings of cowboys, Indians, and landscapes of the American West. Most followers of all things Western know of his paintings, sculptures, and writings. ... What fewer people are aware of are Charlie’s more "earthy" portrayals of cowboy life, including a hand-lettered water-color piece entitled "Just a little sunshine, just a little rain." In it, Russell portrays in four small paintings some of the ups and downs of cowboy life.

The first picture shows a cowhand on day herd. The cattle graze easy on a sunlit plain, the rider slouching in his saddle. Russell entitled this picture, "Just a little sunshine." Picture two shows the cowboy riding herd in the rain, huddled in his yellow slicker, the day wet, cold, and miserable. Title? "Just a little rain." Picture three shows the cowhand well in his cups being helped out of his clothes by a soiled dove in a cowtown bordello. Title: "Just a little pleasure." Fourth picture portrays the cowboy back on the range, in obvious distress because of a "social" disease. The title? "Just a little pain."

In Russell’s painting, Lynde saw a metaphor for everyone’s life journey. In his case, he saw sunshine, figuratively and literally, in the temperate climate and beautiful surroundings in Ecuador. His attacks of bronchitis were “a little rain.” He found “just a little pleasure” in the local culture—food and crafts—and experiencing the lush hillsides around him. And “just a little pain” and “more pain” in the cancer.

But his journey through life, he wrote, “has been a very good journey indeed. May yours contain an abundance of sunshine and pleasure, and only such rain and pain as you may need to provide you with the perfect, balanced life. I’ll keep you informed with regard to my medical problems, life in Ecuador, Montana and the Old West, and life and love in its many forms through this blog. Thanks for following me, and for your support of my work these many years. Hasta luego!”

More details of Stan Lynde’s life and career can be found in my online Journal column, Hare Tonic, for February 2013.