From The Comics Journal #142 (June 1991)

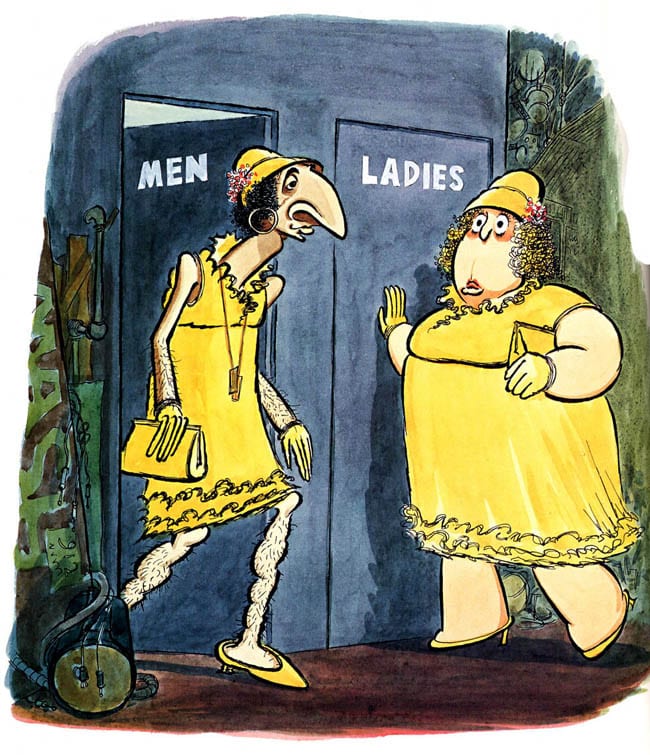

Arnold Roth is a workaholic. But in his case the old adage “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” doesn’t hold true. That’s because Arnold Roth’s work, cartooning, is his play. Roth’s mother used to say he takes his good times with him. For the last 40 years he’s brought that good time to his drawing board — and to what seems like every magazine on the planet (Esquire, Punch, Playboy, National Lampoon, Saturday Evening Post, Sports Illustrated, Premiere, Holiday, Politiks, Smithsonian, Help!, just to name a few). And as if that wasn’t enough to keep him busy, in between freelance assignments Roth has co-edited a humor magazine (Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug), written and drawn numerous children’s books, illustrated book jackets, and drawn the syndicated comic strip Poor Arnold’s Almanac. Arnold Roth is not a perfectionist. He’s the first to tell you that. His approach to cartooning is improvisational, spontaneous, organic — like jazz. (Roth is a jazz musician and aficionado.) He doesn’t do fastidious pencils, if he does them at all. And if his pen happens to slip a little? The results can be serendipitous. Of course, this is not to say Roth’s work is slipshop; au contraire, he’s a true virtuoso. Arnold Roth is a funny guy. His exaggerated, bizarre, highly stylized illustrations are funny, too. The drawings themselves are funny — not just the gags. Like Roth says, the humor is “inherent” in the drawing. As you’ll see in the interview that follows, conducted in the summer of 1989, Roth’s got quite a sense of humor. The kind of guy you’d love to have at your next cocktail party, he’s got a million hilarious anecdotes and he’s more than happy to tell them.

EARLY GIGS

GARY GROTH: I want to start at the very beginning. You were born in Philadelphia and you went to Central High there, and then the Philadelphia College of Art. Did you get a scholarship?

ARNOLD ROTH: Yeah, I got a scholarship from my high school. I was expelled from the College of Art my second year. I was put on probation by Christmas of my first year. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Why were you put on probation?

ROTH: The main thing was I was always tardy. I hate to go to sleep, but then I hate to get up in the morning. It was a very strict school, like a high school. You started at 9:00 a.m. and you weren’t supposed to go out until the bell rang — and you had to be on time. Also I would go out for smokes all the time. You couldn’t smoke in class. If you could have smoked in class I would have been the most prolific student they ever had. I would go out to the big courtyard where everybody was drinking coffee and smoking and chatting up the girls.

GROTH: Were you late to class so often because you were playing sax in jazz bands?

ROTH: I was playing in bands till all hours and having a great time. I played alto sax and a little clarinet. I never turned down any gigs. I would play one job for three dollars, then go play another job for forty dollars. I’d play the worst bar in Philadelphia in a tux because I was then going to the nicest hotel.

GROTH: And the second year you were expelled?

ROTH: They did that by failing me, which is how I lost my scholarship. I didn’t blame them; it was their school. But I must say about that administration, for about eight years in a row, whoever they kicked out did very well. All of them stayed in the art field. The teacher who finally got me expelled — I didn’t know this at the time — told everybody when I entered the school that I was a genius. Then she couldn’t stand it when I didn’t improve. If you start out as a genius, I don’t know how you can improve. That was her analysis, not mine. I could draw well. I had been trained before I went to art school which most people in art school were not — that surprised me.

GROTH: How old were you when you went to the Philadelphia College of Art?

ROTH: Seventeen. I’d been drawing my whole life. I’d been going to art classes since I was about seven or eight. In Philadelphia they had a great place called the Graphic Sketch; two philanthropists had left money to start a school and the best artists in the city taught little kids there. Then the WPA had programs at the art museum which I went to. At the age of nine I actually did real lithographs on stone and helped to print them. That was the whole idea of the program, to learn all that stuff.

GROTH: Can you remember what fueled your interest in cartooning?

ROTH: I just loved cartooning. I’ve always been a wise ass and a fresh kid who liked to make jokes about everything. I’m from a family that likes to joke; we were all that way. It’s like playing in a jazz band — whatever topic came up everybody would put their two cents in and do their chorus on the theme. I just always thought that way. I grew up around popular culture, we were working people who saw comics, movies, anything that came along.

GROTH: Did you read comic strips in the paper?

ROTH: Oh, yeah. I loved them. At that time Philly had about four or five papers — a lot of comic strips. My grandmother had a candy store where she sold the papers — that’s how I got to see them all.

GROTH: Did your parents encourage your drawing?

ROTH: They enjoyed it and I think that’s why I kept doing it. I probably got acceptance that way.

I’m from a family of six kids. We were always the center of attention in my neighborhood because of my grandmother’s store. She had the only three phones in the neighborhood. People had to come in to take their calls or make them. It was really a great life. You saw all the different types; it was like a Dickens novel right in that store.

GROTH: This was during the depression. Were you going through a rough time?

ROTH: No, my father worked through the depression. We were poor but he always managed to keep some kind of a car even. So compared to most people … But it was a poor, working-class neighborhood, predominantly black. The whites were from all over the world. You name a race, creed, or religion, it was represented in that neighborhood.

GROTH: Were your parents immigrants?

ROTH: As children. My grandparents were the real immigrants. My parents were English-speaking. They knew Yiddish, but we all spoke English.

GROTH: So before you even went to the College of Art you had fairly good academic training in drawing?

ROTH: Very academic. I had a great teacher in high school who was a painter. His name was Frederick Gill. Composition was his main interest and it’s always been mine also — how to put things together to make a picture and, in my case, how to tell a story because I’m not doing exhibition pictures. I think the thing he imparted most was the idea of working honest and by that I mean not to go for effect, no tricks … I’ve never tried to describe this concept to anyone …

GROTH: Can you describe a trick?

ROTH: We all have our clichés, like the way you’ll draw the bend of the knee, the back of the pants — to not do that. We settle into drawing in our own manner, but a trick would be a pronounced mannerism.

GROTH: A crutch?

ROTH: Yeah. It’s difficult to explain. He taught me not to go for the cheap shot or the obvious and easy solution — to create a problem for yourself and try to solve it.

GROTH: What moved you in the direction of cartooning and humorous illustration rather than fine art or painting?

ROTH: I had to make a living, and I always liked that world. I always did cartooning, I always drew funny pictures, dirty pictures in a cartoon manner.

GROTH: Before you went to college you learned purely academic skills like anatomy and deep space.

ROTH: Yeah, I knew all that. Although the concentration then was on color composition and the abstract elements of pictures, more so than the academic. I was going to classes and painting in watercolor. I’ve never been much of a opaque painter; I have very little experience with oils. That’s why I work exclusively in pen and ink and watercolor.

GROTH: Isn’t watercolor notoriously difficult to work with?

ROTH: People say that, but not the way I work it. I work in the old British romantic technique which is what people like J.M.W. Turner used in the beginning of the 19th century — wash over wash over wash. I don’t soak out. I hate to redo work and I hate to stay too glued to anything.

To say that there’s a right and a wrong way to do the work, I think that’s crazy. In human intercourse I don’t believe that the ends justify the means, but in artwork it does because it’s the finished product that you’re interested in. I know artists who say, “You shouldn’t pencil, you shouldn’t do this, you shouldn’t do that.” And I say, “Why?” And they say, “Well, uh, it makes it too easy.” Well, should you stand on one hand while you’re doing it? [Laughter.] That’s stupid. When you get dogmatic about technique like that, it gets like religion.

GROTH: Can you describe your experience at the art school? Was it helpful?

ROTH: My mother always said that I take my good time with me. It’s a matter of attitude. I always enjoy wherever I go. I’m not a laid-back guy who sits in the corner and observes. I’m a participator and I love to yap. When I’m asked to give a speech I say, “Sure, I’m already talking. All you have to do is shove the people in front of me.”

I liked the art school. I happened to go right from high school when all the guys — and it was practically all guys in those days — had come out of the army in that big wave of ex-GIs. The art school usually operated with seven hundred students; suddenly they had seven thousand. I think that made it easier for them to kick me the hell out. [Laughter.]

GROTH: When did you learn to play the sax?

ROTH: When I was a freshman or sophomore in high school. I always loved jazz. We always listened to music growing up. With six kids there was a different radio playing different music everywhere in the house.

GROTH: Does your love of jazz continue to this day?

ROTH: Yeah, but I’m pretty much cut off after the ’50s. I listen to the radio and I hear what they’re doing, but I’m what they call a mainstream player — swing, a little be-bop.

GROTH: Who are some of your heroes of jazz?

ROTH: You mean saxophone players? They’ve all been dead a long time — Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, and, one who I hope is still alive, Benny Carter. Wardell Gray was a guy I liked a lot. I could go on and on and on.

GROTH: Did you teach yourself to play the sax?

ROTH: I took lessons from a French guy who was the bandmaster in some private boy’s military school. I didn’t take lessons for an awfully long time. I always learned from the other young players. We’d sit and talk and I’d play for a guy and he’d tell me how to improve. Of course I didn’t have much to tell him — they were usually better players.

GROTH: Were you good?

ROTH: Yeah. I was a good player. During the Second World War once you could play you got work because everybody else was in the army. The big bands were traveling with guys 14, 15, and 16 years old.

GROTH: Did you ever consider becoming a professional musician?

ROTH: No, I would have liked it in a way, but I always wanted to make my living from drawing.

GROTH: What was your first professional illustration job?

ROTH: I couldn’t remember because that would go back to high school. In art school I did a couple of comic books for a guy in Philly — just drawings. I would do little drawings for local stores — for ads and that sort of thing. I couldn’t play saxophone day and night so I had all sorts of jobs in the summer for my day gig. I worked in art factories and in toy factories where I painted eyes on ducks.

GROTH: This was after your two-year stint in art school?

ROTH: No, this is during high school. I worked in an art factory. We made hand-painted pictures; you still see them in framing places. It was just a bunch of people in a room, painting these things. You’d do the trees, another guy would do the skies. Talk about tricks! They had all sorts. We would do the foliage on a tree with a sponge. It went against everything I was learning and liking, but it was a lot of fun.

We worked in tempera a lot. The paintings were for hotels. People would buy huge batches of the things, real five-and-dime stuff. We were selling frames actually. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Did you learn anything doing that?

ROTH: I learned I didn’t want to do it. [Laughter.] But I enjoyed it. Then the guy finished all his contract work and laid us all off. I got another job. I always had to work because of all the kids in my family. I was next to the oldest; my older brother by then was in the army overseas fighting in the war.

GROTH: So what did you do immediately after being expelled from the school of art?

ROTH: I went into business with a couple of guys. One guy was a writer and the other guy had gone to architecture school with my older brother — he was our business brain. The three of us were so inept! The writer’s name was Weakeyes, the guy who ran the business we called Weakheart, and I was known as Weakfingers. I was the artist.

This was in ’48 in the very early days of commercial television. We packaged up a show called Matt … something — that was our hero. It was an animated adventure very much like Clutch Cargo, exactly like it except we didn’t have the movable mouths. We devised a way to do stop animation. It was a series of still drawings with a narration over it, like turning pages in a book. Occasionally we’d get an arm to move and violent action if two guys were fist fighting. We had a lot of companies interested, but we never got a sale. I was still playing in bands because that’s how I was making any bread at all. Then I got tuberculosis and got sent to a sanitarium for over a year.

GROTH: Really?

ROTH: Well, somebody had to get it. It’s a whole disease, can’t let it go to waste. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Where was the sanitarium?

ROTH: In Browns Mills, New Jersey.

GROTH: Were you essentially being quarantined?

ROTH: Yeah. It’s a contagious disease. If you have it you carry it until you stop coughing the germ around. When I went in the sanitarium, there were people that had been there 25 years. The only thing for them was rest and fresh air. Then they developed these wonder drugs. They changed the whole treatment for TB; it was like a miracle cure. They didn’t give them to me but other people were getting them. For ten years I took pneumo-thorax treatments. They pumped air in my chest to keep one of the lungs depressed. I’d go every Friday and the guy would pump in a cleanser can full of air. Then the air would dissipate and I’d feel it bubbling around. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Why would they want to collapse part of your lung?

ROTH: It rested that part and gave it a chance to calcify and cure. But they never say “You’re cured.” They say, “It’s arrested.”

GROTH: Was that depressing?

ROTH: No. I don’t like self-pity. It doesn’t do anybody any good. I loved to read and I got a chance to read everything — my lungs got better and my eyes fell out. When I got out I went back to art school for a couple months. My mother was dying of cancer so I quit art school to take care of her, about half a year, until she died.

She left me seven hundred bucks and I just freelanced. The first year I was working I operated at a loss. That summer I think I was a one-man art department in a printing plant. Then I got a portfolio together. Portfolios I could do in a week because I worked fast. I did big, fancy, crowded drawings of lots of people and funny things, and I would hustle like crazy.

GROTH: To whom would you hustle these things?

ROTH: I’d go to all the magazines. I’d try every place in Philly; I’d go up to New York. Eventually, I learned the obvious: not to go to places where I didn’t want to work — although I was hungry for every buck I could get. It’s a waste of time to go somewhere just because they need artwork, but not what you do.

I did nickel and dime jobs. I did — they still sell them in Woolworth’s — little Pennsylvania Dutch lampshades. They were putting up Levittown then. I did silk screen designs and designs to be reproduced on glass for the kitchens. Some of the designs I made up, other were patterns they had accepted from other people. You name it, I did it. I made nothing, five or ten bucks here or there. I didn’t want to start doing realistic illustration or even stylized illustration, which is what they would buy readily. I wanted to draw the way I drew and sell my thinking too.

GROTH: You wanted to be a cartoonist throughout?

ROTH: Absolutely.

GROTH: What kind of cartoonist?

ROTH: I wanted to do humor. I was frothing at the mouth to get in The New Yorker and they were very interested in what I had. An editor there went through my stuff, sort of giving me a critique. Finally, he said, “You know you keep making wise cracks. Are you sure you understand what I’m telling you?” I said, “Well, I think you’re telling me I should draw more like Cobean.” Sam Cobean was a terrific New Yorker cartoonist who had recently died in a car crash. He said, “You have to make up your mind if you want more than anything in the world to be a New Yorker cartoonist.” I said, “No, I want to screw and drink and smoke and cock around.” He looked at me and he was really serious. He repeated the question. I told him no and I never went back. That was the end of me, there.

GROTH: Why did you do that instead of giving him the “right” answer which would have been, “Yes, sir.”?

ROTH: I knew what their system was and I knew it was a system I didn’t like. I don’t like to do sketches. I don’t like to do things over and over. I don’t like it when they say things like, “If this guy’s finger was a little blunter, or this eye was straight …” I don’t work well under those circumstances. That doesn’t mean that I’m always right and they’re always wrong — but it’s my work. I have to make my mistakes my way, and when I make it good, make it good my way. Other people can work that system and they do terrific work. I would be miserable. I’d rather work in a grocery store — but I’d like to say where the cans go. [Laughter.]

GROTH: Was there an authoritarianism to this guy’s attitude that you resented?

ROTH: No, no. He’s a good guy. I’m not going to say his name. I know him well to this day and I like him. He’s a very good cartoonist himself. But he was a guy who believed in The New Yorker and was dedicated to it. The New Yorker was supposedly the height of sophistication. And it was great. If you were looking for the best American magazine gag cartoonists they were for sure in The New Yorker. They didn’t have every good cartoonist, but they didn’t have any bad ones.

GROTH: Why did you go to The New Yorker if you didn’t particularly want to work for them?

ROTH: It was the prime market. Your career was made if you got in The New Yorker. It’s true to this day. People in the advertising business, the publishing business — they all look at it. They don’t read it; it’s the only weekly magazine that has pieces in it that take seven weeks to read. But as the New Yorker cartoonists say, “no cartoon goes unread.” When someone wants to plan an ad campaign that’s sophisticated or a little stylish, they know the work of all those cartoonists. Not every cartoonist there has had a huge career like Saxon or Charles Addams did, but it was for sure a showcase.

GROTH: This was around ’51 or ’52. Were you paying attention to comic books?

ROTH: Yes, but not anymore. My interest in comic books started to wane in the late ’40s. Around that time Paul Desmond, who was in the Dave Brubeck Quartet, introduced me to Mad magazine.

I met Paul through a fluke. I shared a studio with 11 guys. This was in ’52, the same year I got married. For most guys it was a mail drop and a phone number, but about three or four of us worked there all the time. One guy was a photographer and he had advertised a camera for sale. The Dave Brubeck Quartet had just arrived in town. They were going to play for five weeks in Philly. The guys in the group saw this ad and wanted to buy the camera for Paul Desmond for his birthday. When they walked in the studio and said his name I immediately knew who he was. I knew their work very well. After that we were very close for years.

Anyway, Paul’s the one who showed me Mad magazine. I had missed it even though I leafed through things in the comics rack. He gave me two issues or so that he had picked up. Then I started getting Mad all the time.

I would look through, say, Tales From the Crypt — I can’t tell you the titles anymore. I looked at war comics and all those genres that were running. I knew the names of the artists and I knew what their work looked like.

GROTH: Had you thought of pursuing work at a comic book publisher?

ROTH: I would have, but I didn’t see any place for me until I saw Mad. The kind of work I wanted to do, the only markets were in magazine spreads. Most comics were serious and the funny ones were so hokey; they were like the worst syndicated things. I was interested in being a little more sophisticated. Mad was not all that sophisticated, but it had my outlook and that was the major thing. It wasn’t just doing “Hey, pop you didn’t pull up your suspenders”-type jokes. It was commentary, a perception, an attitude.

ROTH AND KURTZMAN

GROTH: When did you get your first break?

ROTH: Holiday was one of my first big breaks. I got steady work from them every month. I would do little drawings for essay pieces in the front. It was a big, beautiful magazine. I sold a couple small spots to Charm magazine. I used to go to New York by train to show my work to as many people as I could. I worked like crazy. Every week I had a completely new set of drawings to show.

I started working for TV Guide in ’52. I did a teeny drawing for an art service in Philly that called me. It was a drawing of where the cameras would be located for Eisenhower’s inauguration in January, so I must have done it in November or December. TV Guide came out right around then; I had done the drawing for their dummy issue. TV Guide was my one really good, steady account. But I never did more than one a week. Soon after I started to sell more bits and pieces in New York.

GROTH: How long did you work for TV Guide?

ROTH: I still do. I just did one for them a few months ago. This year was the first time that they’ve called me and I’ve been too busy to do the job. I used to stay up all night just to accommodate them because of our history. I’m getting too old for that now.

GROTH: These were all interior illustrations?

ROTH: Yeah, I’ve never done a cover for them in all those years. I’ve done covers for practically every magazine in the business, but not for them.

GROTH: You started Poor Arnold’s Almanac in 1959, but what were you doing between ’55 and ’59?

ROTH: In ’55 or ’56 a fellow named John Hubley — a terrific animator, one of the guys who did Gerald McBoing-Boing and Mr. Magoo — had an outfit called Storyboard, Inc. He had two guys working on ideas in-house, Bob Blechman and Gene Deitch. They also used three freelancers. I was one of them. The other two were famous cartoonists — one was Crockett Johnson who had done the comic strip Barnaby. I would write funny stuff and design characters that had a tenuous application to a product, and they would film it with stop-motion animation. Ad agencies were keeping these bits in a brain trust. It was good bread for me and I could do that stuff fast.

I guess I was talking to Blechman and Ed Fisher, who’s a New Yorker cartoonist, and they told me about Trump. They said that they or Harvey Kurtzman had mentioned me and why don’t I go see him. I thought, “Wow, those guys are great, the guys who did Mad.” I went over and Harvey put me on a retainer.

GROTH: What year would that have been?

ROTH: Late ’56. Here’s a picture of us that ran inside the cover of one of the issues, [showing it to Groth] There’s Jack Davis and Will Elder. They did drawing. There’s Harvey. That’s Harry Chester, he’s in production — he’s done well producing magazines. There’s Al Jaffee and that’s me. Those two other fellows were the art director and his assistant.

GROTH: Harvey had hair.

ROTH: Yeah, Al didn’t have a beard or a mustache.

GROTH: And you all had the same suit. [Laughter.]

ROTH: That’s true. That’s the ’50s for you. Harvey and I felt that we were soul mates so I wrote and drew a lot of stuff. But you know the history of Trump — we were out of business before we hit the stands. Hugh Hefner, the publisher of Trump, had to fold the magazine because the bank called the loan in.

GROTH: Why did they call the loan in?

ROTH: All the banks got nervous about their publishing loans, which are never good loans anyway. All the huge magazines were starting to get shaky, The Saturday Evening Post. The money men folded Collier’s precipitously. It was strictly a business manipulation; somebody made a lot of money by doing it. Collier’s was not doing poorly; it was one of the top magazines in the country.

Hefner had not put up any collateral — this is as I heard the story. He was the boy genius of Chicago because of Playboy which had been booming for about four or five years. The bank asked him to put up pieces of Playboy as collateral and he wasn’t going to do it. So they called the loan in and he lost money.

Harvey’s always told me that we would have been making money by the fourth or fifth issue. He said some of the most famous writers in America were coming to the Trump office looking for work. We would have been publishing every other month. It was an expensive magazine; we had a lot of color and fancy production — too much so, I think it detracted from the work — but it made an attractive package. So then Hefner, being contrite about it, gave us office space. He was in the MCA building near 57th and Madison. We put out Humbug as partners.

GROTH: That was a collaborative venture amongst several artists?

ROTH: Yes. We all bought stock and worked for free, except, I think, for Jack [Davis]. We sort of chipped in to pay Jack.

GROTH: Who was “we all”?

ROTH: Al, me, Harvey, Willie, Harry Chester — I think we were the only ones — there was six of us.

GROTH: How did that go?

ROTH: It didn’t go well. It’s like a comedy: just as we were going to come out the biggest magazine distributor folded suddenly. The company was the American News Service which distributed publications and owned newsstands in every transportation center and most of the desirable street corners — they owned the newsstands where they sold magazines. When they went out even The New Yorker didn’t have a distributor. These huge magazines were out of luck and here we were with this 15-cent magazine printed on newsprint. We got what we could, a distributor who wanted us to do Cracked magazine, an imitation of Mad, every other month — in addition to doing Humbug every other month. The partnership was not one we found attractive. We always just missed making money according to them. We had to take their figures; there was no way to prove that they weren’t on the up and up. After 12-13 issues, whatever it went, we knew were never going to get a real accounting.

GROTH: Harvey once told me that the distributor he dealt with was a pretty dangerous character. Apparently, the distributor really tried to rope you into a hell of a one-sided deal.

ROTH: Yeah. At our last meeting he was trying to coerce us into doing what he wanted. This is a gentleman of Sicilian origins and he had hands like hams and fingers like salamis. And on each finger he had a ring. He held up his hands and said, “You listen to me you get a ring on every finger. You don’t listen to me … ” and he made a huge fist. Harvey said [Roth squeaks in a high voice] “Well, gee, we’ll talk it over.” We got together and said, “We’re out of business. We don’t want any part of this.”

GROTH: Did you get to know the artists?

ROTH: Yeah. We had all known each other from Trump, but during Humbug we got to know each other better. I liked everybody. I think we all liked each other. Jack was the same way he is now: sort of shy, a big gosh-golly kind of guy, self-effacing, soft-spoken, always easy to get along with. Willie was cuckoo, which he always was and I’m sure still is. I haven’t seen Willie for four or five years now. Al I see a lot. I have dinner with him four or five times a year. He’s right here in town. Harry Chester is a wonderful and funny guy. Harvey of course was the editor. The guys we hired as art directors were very good, but I don’t remember their names.

I’ve got lots of stories about those days. One winter there was a horrible, monumental blizzard; it was measured in feet, not inches. Jack was driving us all back to New York from Connecticut after a meeting with the distributor. He had a great big, heavy station wagon — especially with six of us in it. Still, we were sliding and slithering around. We were all dying of hunger, hadn’t eaten all day, and here it’s night, pitch black. You couldn’t see anything, just tops of abandoned cars covered with snow. Finally, we see this neon sign just off the edge of the road. It says Red Barn, and the windows are lit. So we slide off the Merritt Parkway down into the parking lot and the six of us come piling in the restaurant. Here’s this beautiful place — pine tables, red-and-white checkered table cloths, western lamps — about 80 tables and there’s not a person in there. The door opens from the kitchen and this middle-aged woman with her hair in a bun, the most motherly looking woman you could draw, comes out in an apron. She looks at us with this big smile on her face and Willie Elder says to her, “Don’t worry, we’re all married.” She turned around and went right back into the kitchen, scared to death. [Laughter.] Finally, we got her to come out and feed us. Willie had a way of putting people at ease — so they wanted to commit suicide rather than be tortured to death.

Once when things were getting a bit depressing after a few issues of Humbug, Harvey was giving us all a sort of pep talk. Harvey’s back was to the windows. About 80 feet away there was another building at least as high as ours. We were looking at Harvey and he waved his arm to the window and said, “Remember they’re all out there.” Like in a movie all our eyes went to the end of his hand and out the window. Right across in the window of the other building there was a guy screwing a woman on a couch. [Laughter.] We all leapt to the window; he didn’t know what the hell we were doing.

GROTH: What was Harvey like to work for?

ROTH: Harvey is a honer, as I say, and I’m not. I draw something and say, “That’s the best it’s going to be.” When I would have fights with Harvey it would be about that. In terms of writing, I would defer to Harvey, but I’d argue like hell with him. Sometimes he would rewrite completely, sometimes he’d only alter a part. But our fights were never anything personal, it was just work. Harvey’s not a bully and he’s not a sleaze. I like to work for a guy like Harvey.

I think the thing cartoonists anguish over is whether it’s clear — not obvious, but clear. It might not be an obvious idea, but if it’s not clear it’s illegible. Harvey was very good about that. At first I was stubborn. I didn’t realize how much I could learn from Harvey. Then once I started to get the idea, I did.

Occasionally, I would stay with Harvey. I lived in Philly and if we worked very late he’d take me to his house in Mount Vernon and I’d sleep on his couch. He’d always wake me up with his laughing record — this guy playing a trombone and all these people laughing. It was torture because I hate to get up.

I’ll tell you one of my favorite stories that to me perfectly describes Harvey the editor — and it doesn’t even have to do with editing. Harvey gave a huge party at his place; it might have been when he started Help!, or one of the other magazines. He knew all the cartoonists and they were all there — all these funny guys. This huge living room was jammed. Everybody was drinking and laughing. There was a fever-pitch pace to it, an incredible din, everybody’s having a great time. Suddenly somebody’s saying, “People, people … ” like at camp or something. So everybody quiets down, the whole rhythm of the party is absolutely destroyed — the British would say you took the mickey out of the party. We turn around and here’s Harvey standing on the piano. He says, “People...” and we’re all quiet now, “I want you all to have a great time.” Then everybody went home. He killed the whole party. He had to edit the party. [Laughter.] That’s a typical Harvey Kurtzman story. Who knows, maybe he wanted us to get the hell out, it was his house.

GROTH: Did Harvey’s drawing influence you?

ROTH: No, I didn’t know his drawing that well. I love Harvey’s drawing and I’ve always been very dismayed that he didn’t do much with it. It’s got that nice, free, loose look. It’s very strong graphically, tells the story beautifully. It does everything you want it to do.

GROTH: Up to that point what artists or cartoonists were influencing you? Where did you derive inspiration?

ROTH: We’re all influenced throughout our lives. You’re not as influenced as you get older because you’re not as open to it. When I was young, like everybody else, I liked to think I was the most original guy who ever was born. If you had asked me, “If you’re so original, how did you invent cartooning?” I would have paused to think about when I had.

I’ve always been a great reader of history and I knew cartoon history very well. I knew the British cartoonists from the 19th century very well, Gilray, Rowlandson, Cruikshank. I could buy little books of their stuff reprinted from Punch for a nickel or a dime in used bookstores. I just pored over that stuff. I knew them better than the 19th century American cartoonists. All of them influenced me. The one guy who everybody says must have influenced me is Ronald Searle — and I’m sure he has — but I think we come from the same pool to begin with. Searle and I are about the same age, he’s a little bit older. I used to see his stuff from the late ’40s and early ’50s in Punch. Sometimes I can see the influence, but I think it’s like confusing Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster. But if we’re in the same school, Searle is the leader of the school.

GROTH: Art Young?

ROTH: Art Young — I knew all those guys’ work, The Masses cartoonists. I knew all the political cartoonists as well.

GROTH: A lot of the cartoonists you mention are very political, like Rowlandson.

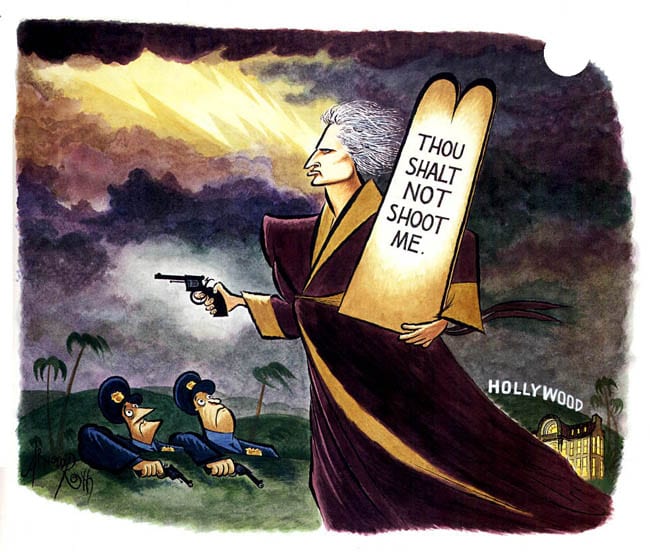

ROTH: I’ve always been very interested in the drawing, the jokes can take care of themselves. My ideal cartoon is one in which there are no words. The bullshitters use terms like this so I hesitate to say it, but there’s an inherent humor in the drawing, too.

GROTH: Were you interested ever in being a political cartoonist?

ROTH: Not really. I did do comics with a political slant — I did them in Humbug — but I never wanted to be a full-time political cartoonist. Political cartooning in America was always very sanctimonious and heavy, especially in those days. Wealthy, conservative publishers told the cartoonists what to do.

A big breakthrough came around the time that cartoonists here became aware of the British and European traditions. The British, I think, are the best of them. I’ll tell you who really made an impact, a English cartoonist named Giles. He did cartoons during the war that were funny. They could be poignant and all that, but a lot of them were just jokes. Then when Oliphant came in, if you weren’t hip to that, he made you be. I love his work and I love his attitude. He cuts everything to mincemeat.

My measurement of politicians is so low. When I was young I took politics seriously, I took life more seriously probably.

GROTH: You think so?

ROTH: Well, it seemed a lot more permanent. [Laughter.]

GROTH: I guess it gets more temporary —

ROTH: Every day, every day.

THE MCCARTHY ERA

GROTH: Before we leave the ’50s, I want to ask you a few more questions about that era. How did you feel during the Senate subcommittee hearings on comics that segued either into or from the McCarthy era? Were you following that closely?

ROTH: I followed politics very closely then. I thought those hearings were horrible and rotten. I don’t like censorship of any form. We all use our own discretion; I’m not going to subscribe to the KKK’s magazine, but I don’t want to anybody to tell me that I can’t. That whole thing was a political public relations thing. Everybody connected with the hearings was making their names. Kefauver wanted to run for president, and eventually ran for vice-president. The guy they used as the researcher was named Legman. I met him years later; he has this huge collection of pornography in Europe. And they were all so self-righteous.

If you say you’re polluting kids with Tales from the Crypt … I’m sure it gave a lot of kids bad dreams. I saw Bride of Frankenstein when I was a kid and it scared me — that was the purpose of it, but I got through it.

At that time I was living with my wife and kids in a crummy neighborhood in Philly. A middle-aged merchant seaman was accused of molesting an 11-year-old girl. In his room they found Playboy and some other magazines. There was this woman — I can’t think of her name — a widow of a Philadelphia politician, who made her political name by saying this guy molested the girl because he had read all that stuff. She eventually went on to Eisenhower’s cabinet. While that furor was going on a 22-year-old student at the Pillar of Fire Bible School in North Jersey raped and killed a 25-year-old mother of an infant. This guy only read the Bible. Nobody said he committed that crime because he was reading the Bible.

So when the Kefauver thing started and they talked about the great harm comics were doing to children and blah, blah, blah, they just wanted to scare parents and make their names. It goes on today, too, like this mother’s thing about Saturday morning cartoons. I don’t trust any of those people. They’re usually self-aggrandizers. I think they have a legitimate concern about what their kids read or see. I don’t think you can keep the kids from it, but I think you can explain it to them. You should talk to your kids — not propagandize but try to establish a balance. If they’re afraid to even mention that they read stuff like that then I think you’re being a fool. That’s what the problem is, not what they read.

GROTH: You’ve said, “The 1950s were not as dull as people will tell you. There were the hips and non-hips, there was jazz, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, and a lot of people fighting McCarthy and the various legislative clones.” And before the interview you were talking about the humor of the ’50s and so on. I was wondering if you might elaborate on that and talk about what life was like in the ’50s, in terms of cartooning and humor.

ROTH: There was an explosion. Because of the Second World War, by the time everybody came back and went to college on the GI bill, it was like eight years didn’t happen. By the late ’40s you had not only young guys out of high school and college, but guys in their ’30s establishing their careers. Suddenly you had this tremendous pool of talent.

Underground comics came out in the ’60s, but you couldn’t be underground in the ’60s — underground was overground really. Guys wearing Indian headbands were smoking pot and peeing out on the corner. How can you be underground amidst that? An insurance salesman sneaking around selling insurance — he’d be underground.

In the ’50s there were lots of people with liberal ideals — although it seemed the tenor of the times was very conservative. And they weren’t just a handful of people. I love this idea that the ’60s was this big explosion of liberalism. They were all fighting the establishment while wearing Budweiser T-shirts. Then later when they got a few bucks they started wearing clothes with Gucci emblems. In the ’50s very radical guys dressed in tweed jackets and slacks, just like the guys they disagreed with.

My wife, from the day we met, was always a volunteer at Planned Parenthood. In the McCarthy era I went and testified that guys were not communists. These men were accused of being communists because they had a copy of the Modern Library version of Das Kapital on their shelf or a picture by Diego Rivera. It was really that stupid. I remember I testified for one guy who was accused of being a member of a communist cell in Reading, Pennsylvania — which was 50-75 miles away from Philadelphia — when he was three years old. He had supposedly gone to meetings twice a week. [Laughter.] I don’t know how he went; his mother wasn’t accused, he was.

GROTH: You testified?

ROTH: Not in court trials. They were usually hearings before the postal board, for guys I knew who worked in the post office. Nobody knew who accused them; there would be an unsigned letter. Usually it was Italian or Jewish guys who were being accused; black guys would have, I guess, but they couldn’t get jobs with the post office to begin with. The guy who was defending himself would always get a Quaker lawyer and they would have this hearing with witnesses. I didn’t spend my whole life with these guys, but I knew they weren’t communists. I knew communists in the ’30s. If they were communists it was so hidden that whoever wrote that letter for sure didn’t know. I would go and tell them what I knew. And my wife would too, if she knew them.

GROTH: So you were testifying as to their character. It’s a little obscene that you even had to testify that they weren’t communists because they should be able to be communists and still hold those jobs.

ROTH: I agree with you, yes, although I’m not a great lover of communists — or fascists. There’s a sentimental idea that communists are not as mean — and it was true over here. Anyway, we’d testify and the guy, invariably, would get fired. Most of them were ex-GIs — that was the killer. Years later, some of them sued and got back pay from the Post Office. It was an interesting period in which to observe people. There were a lot of really sad and horrible stories. A lot of harm was done to innocent people. But I knew a lot of those guys who the McCarthyites were going against and they would have done the same thing if they had been in power. They thought that way themselves. They wanted to punish evil-thinkers, too.

Continued